LAW

COMMENTARY: Protecting healthcare privacy: Analysis of data protection developments in India

Paarth Naithani

Published online first on December 18, 2023. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2023.078Abstract

Patient privacy is essential and so is ensuring confidentiality in the doctor-patient relationship. However, today’s reality is that patient information is increasingly accessible to third parties outside this relationship. This article discusses India’s data protection framework and assesses data protection developments in India including the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023.

Keywords: healthcare, data protection, India, law, Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023

Health privacy — A key ethical challenge

The importance of privacy was acknowledged as far back as the time of the Hippocratic Oath [1]. Both consequentialist and deontological ethical justifications exist for protecting privacy in the patient–provider relationship [2]. This is essential, given the fiduciary nature of the doctor-patient relationship and the mutual expectations of trust between patient and doctor [3] . Privacy in healthcare has many facets, including informational privacy, physical privacy, associational privacy, proprietary privacy and decisional privacy [3].

The issue of privacy in healthcare came up in India in the 1998 case of Mr X v Hospital Z. Mr X was found to be HIV+ when he donated blood. The allegedly unauthorised disclosure of his HIV+ status by the hospital [4] resulted in Mr X’s marriage being called off, leading him to seek legal redress. The Court held that doctors must maintain secrecy about their patients. However, the Court also held that “public interest would override the duty of confidentiality, particularly where there is an immediate or future health risk to others” — in this case the risk to the health of the woman who was to marry the appellant.

In another case, the Supreme Court of India stated that a hospital’s unauthorised disclosure of medical records is an invasion of privacy [5] . Furthermore, that when such data are required for legitimate purposes such as analysis of an epidemic, the anonymity of individuals must be preserved [5].

Risks of health privacy breach in India

Health privacy is vital as data can be misused in multiple ways by employers, governments, and other third parties to treat individuals differently while providing services, benefits, and employment [6]. For instance, unauthorised access to health data can harm individuals suffering from stigmatised diseases, as also those with mental health problems [7]. Cybercriminals can breach the security of health data to blackmail individuals or indulge in identity theft [7]. When artificial intelligence is used to analyse de-identified health data, the data are at risk of being re-identified [8]. These risks are not limited to individuals but extend to family members about whose health conditions inferences can be made [9]. Risks also arise from the analysis of seemingly unrelated information such as social media posts, credit card history, and online behaviour [9]; for instance, inferences can be drawn about the possibility of depression from the purchase of plus size clothes [9].

Violations of privacy in the healthcare sector in India include healthcare providers not specifying the purpose of collecting data, collecting more health data than required for processing, sharing health data for research without de-identification and anonymisation, revealing health information to third parties without consent, lack of security safeguards for health data resulting in breach of data confidentiality, and not informing the data principal in case of data breach [3].

These concerns are exacerbated by the high illiteracy rate, lack of privacy awareness, and questionable informed consent in India. People may not understand the privacy implications of their health data being processed, or how to protect their health data, especially when using online services. Thus, several concerns arise regarding informed consent and data protection. While informed consent is required before a doctor operates on a patient to ensure that the patient understands the medical procedure and agrees to it, consent in the context of data protection is required so the patient’s personal data can be processed only after they have understood how and why it will be processed.

Impact of rapid digitisation on health privacy

Privacy issues in healthcare are gaining huge significance because of the increasing collection of individuals’ health data, such as through the Internet of Medical Things, including wearables such as fitness watches [6]. There has also been a proliferation of mobile applications and websites for telemedicine, counselling, wellness, and sale of medicines that collect health data. Big Medical Data is analysed using artificial intelligence (AI) and data mining and matching techniques to generate new medical insights [10]. This means a person’s health information is now increasingly available to various third parties outside the doctor-patient relationship, with the possibility of privacy harm including loss of reputation or humiliation, discriminatory treatment, blackmail or extortion, mental injury, denial or withdrawal of services, and restrictions on speech for fear of being observed or surveilled [11]. These harms had been recognised in the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, which was one of the initial proposals for comprehensive data protection legislation in India, now replaced by the enacted Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023.

Can the existing data protection framework in India ensure adequate protection of healthcare data privacy? The following sections analyse India’s data protection framework from this perspective.

Analysis of key provisions of India’s data protection frameworks

The framework on data protection in India had consisted of the Information Technology Act, 2000 [12] and the Sensitive Personal Data or Information (SPDI) Rules, 2011 [13]. To replace this framework, several draft data protection legislations including the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 [11] and the Data Protection Bill, 2021 (DPB 2021) [14] were discussed before the recent enactment of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023 (DPDP 2023) [15]. In addition, health-specific data protection frameworks have been proposed in India, including the Digital Information Security in Healthcare Act (DISHA) [16] and the Health Data Management Policy, 2022 (HDMP) [17].

With the enactment of the DPDP Act 2023, in India, Section 43A of the IT Act, and the SPDI Rules, passed under Section 43A, have been replaced. The proposed health-specific data protection frameworks, including the HDMP and DISHA, are sector-specific frameworks that have not been made redundant by the recent general legislation, DPDP 2023.

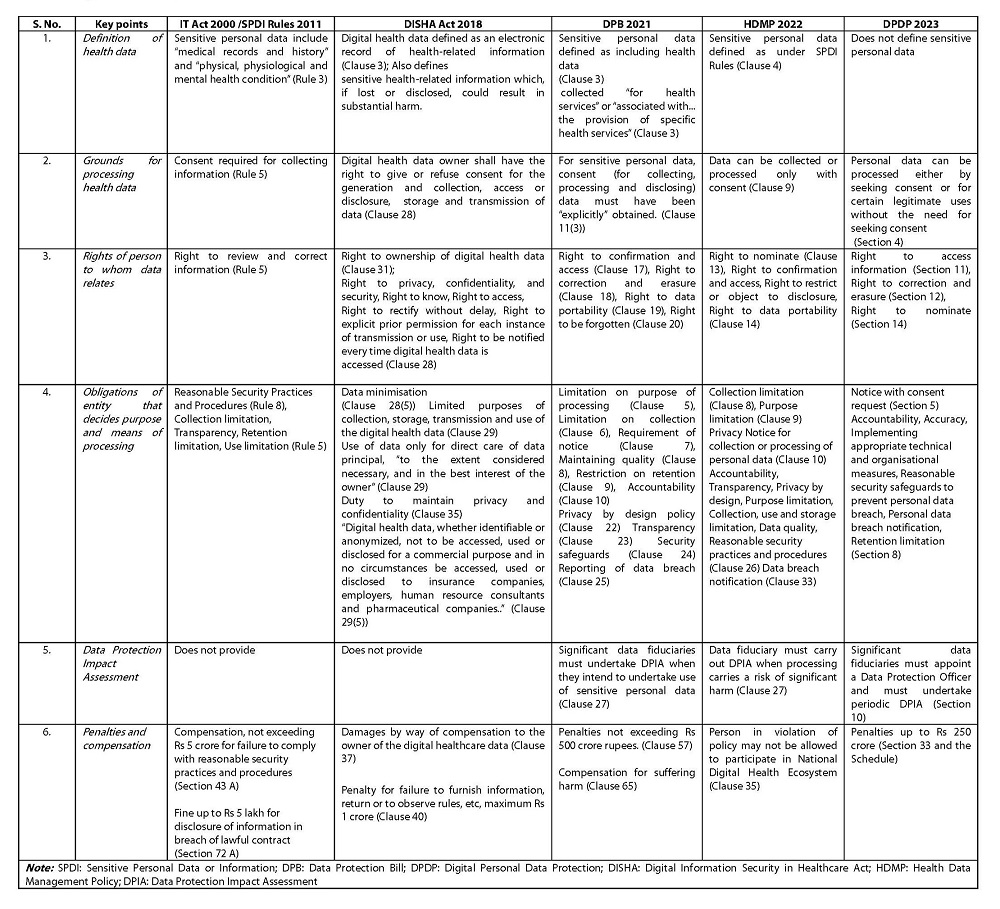

Table 1 summarises the key provisions of these frameworks.

Table 1. Key points of data protection frameworks in IndiaAs the table indicates, as distinct from the other data protection frameworks, the DPDP 2023:

• does not define sensitive personal data;

• allows data processing without explicit consent — which has a higher threshold than regular consent;

• does not provide to the data principal the rights to ownership, to restrict or object to use of data, to data portability, or to seek compensation;

• does not mandate the use of health data only in the data principal’s best interest and for direct care, or restrict the processing of health data for commercial purposes, or ensure a privacy by design policy;

• does not require a Data Protection Impact Assessment for all data fiduciaries processing health data.

Inadequacy of the past frameworks

From the ethical standpoint of maintaining patient privacy and confidentiality, the SPDI Rules and Sections 43A of the IT Act were inadequate, in that they only applied to only to a body corporate processing data (body corporate had been defined in section 43A of IT Act as “any company and includes a firm, sole proprietorship or other association of individuals engaged in commercial or professional activities.”) These frameworks also failed to protect patient privacy, as data processing is invisible and health data can be shared and processed by multiple entities unknown to the data principal.

This framework failed to tackle the following issues:

• Individuals lack awareness about privacy policies and implications of consenting. Individuals rarely actually read and understand privacy policies and make educated consent decisions;

• Reasonable security practices and procedures put in place by companies did not prevent breach of health data;

• The SPDI Rules do not seem to have sufficiently deterred misuse of data as they didn’t provide for high penalties.

Overall, the data principal did not have control over the use of data once consent was given for the data to be processed. While the framework did provide for compensation for harm caused by breach of data, the question remained of whether harms such as loss of reputation can ever be adequately compensated.

Analysis of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023

As per DPDP 2023, the enacted data protection legislation in India, personal data can be processed only with consent or for certain legitimate uses (Section 4). An individual’s consent “shall be free, specific, informed, unconditional and unambiguous with a clear affirmative action, and shall signify an agreement to the processing of her personal data for the specified purpose and be limited to such personal data as is necessary for such specified purpose.” (Section 6).

When consent is sought, information must also be provided containing the description of personal data and the purpose of processing it (Section 5). Section 7 specifies that data can be processed for “certain legitimate uses” on the condition that the Data Principal has voluntarily provided her personal data to the Data Fiduciary, and “has not indicated to the Data Fiduciary that she does not consent to its use”. Other conditions for certain legitimate use of data include “responding to a medical emergency involving a threat to the life or immediate threat to the health of the Data Principal or any other individual” and “to provide medical treatment or health services to any individual during an epidemic, outbreak of disease, or any other threat to public health.” (Section 7).

The DPDP 2023 has reduced the level of protection for health data compared to the DPB 2021.

• Unlike the DPB 2021, the DPDP 2023 does not define health data and does not categorise data as sensitive personal data.

• Unlike the DPB 2021 which required explicit consent that cannot be inferred from conduct in context, the DPDP allows data processing when data is voluntarily provided. This raises several concerns. Will the data principal be aware of the scope of the processing? If adequate safeguards are not provided, can “certain legitimate uses” be abused for secondary processing of data, affecting the data principal’s privacy? The privacy of individuals can be affected when the scope of processing is not clearly defined and there is no limitation of purpose. It could lead to the processing of health data for various secondary purposes, such as commercial purposes, which go beyond merely providing health services. When the health data is misused for unspecified purposes, it could lead to harms such as discriminatory treatment of data principals, breach of privacy, and loss of control of health-related data.

• The DPDP 2023 lowers the level of protection provided in DPB 2021 in another way. Section 10 of the DPDP 2023 defines significant data fiduciaries and requires them to undertake data protection impact assessment. A data protection impact assessment requires describing “the rights of Data Principals and the purpose of processing of their personal data, [and] assessment and management of the risk to the rights of the Data Principals” (Section 10, DPDP 2023). Such an assessment was mandatory for processing sensitive personal data, under the DPB 2021. The DPB required significant data fiduciaries to carry out a data protection impact assessment when they intend to undertake processing involving the use of sensitive personal data (Clause 27). On the other hand, the DPDP 2023 lowers the level of protection, as it does not define sensitive personal data and therefore, does not mandate that significant data fiduciaries need to undertake data protection impact assessment for processing sensitive personal data.

The level of protection under the draft HDMP is greater than under the DPDP. While the HDMP makes explicit consent necessary for processing personal data, the DPDP allows data processing on the ground of certain legitimate uses when the data is voluntarily provided. The HDMP provides rights to the data principal that are missing in the DPDP 2023. For instance, the HDMP provides the right to restrict or object to disclosure of personal data by the data fiduciary, and the right to data portability which makes the data available to the data principal in a commonly used format, which can be shared easily (Clause 14). While the HDMP requires provision of a privacy by design policy, the DPDP 2023 does not recognise the principle of privacy by design. However, the DPDP provides for a higher maximum penalty than the HDMP. Moreover, while matters go to the Data Protection Board of India under the DPDP, grievance redressal under the HDMP involves approaching the data protection officer of the data fiduciary followed by the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission grievance redress officer ABDM-GRO (Clause 32).

The question is: when the HDMP and DPDP provide for different standards of protection, which would take precedence? Would the HDMP prevail as it is specific to the health sector, or would the DPDP prevail as it is a legislation and not a policy like the HDMP?

Conclusion

Today, health data is accessible to agencies outside the confidentiality of the doctor-patient relationship. How then should the individual’s privacy be maintained given the sensitivity of health data and risks of harm?

The following measures need to be taken: Health data as sensitive personal data should be provided with a higher level of protection, with stricter security safeguards than for other data, and processed with transparency and only after taking the patient’s informed consent. Identifiable health data should be used only for the limited purpose of providing a healthcare service and its commercial use should not be permitted. There should be a timebound requirement for carrying out data protection impact assessments for healthcare providers. Privacy should be protected by design, strict penalties should be imposed for violations of health data protection provisions, and there must be high compensation for breach of health data privacy.

There is an urgent need for robust data protection for health data to protect patient privacy. While digitalisation of health data is inevitable, data protection framework must seek to achieve and enforce strict confidentiality of health information between the doctor and the patient.

Statement of any submissions of very similar work: None

References

- Arenas A, translator. Hippocrates’ Oath. Boston University website. Cited 2023 Oct 10. Available from: https://www.bu.edu/arion/files/2010/03/Arenas_05Feb2010_Layout-3.pdf

- Jain D. Regulation of Digital Healthcare in India: Ethical and Legal Challenges. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 Mar 21; 11(6):911. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fhealthcare11060911

- Mani T. Privacy in Healthcare: Policy Guide. Centre for Internet and Society. Centre for Internet and Society website. 2014 Aug 26[Cited 2023 Oct 10]. Available from: https://editors.cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/privacy-healthcare.pdf

- Supreme Court of India. Mr X v Hospital Z. Appeal (Civil) 4641 of 1998. 1998 Sep 1[Cited 2023 Oct 10]. Available from: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/382721/

- Supreme Court of India. Justice K.S. Puttaswami and another Vs. Union of India. Writ Petition (Civil) 494 of 2012. 2018 Sep 26[Cited 2023 Oct 10]. Available from: https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2012/35071/35071_2012_Judgement_24-Aug-2017.pdf

- Gaba J M, Estremadura J M. Data protection of biometric data and genetic data. Ateneo Law Journal. 2020[Cited 2023 Oct 10]; 64(3):949-982. Available from: https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/ateno64&i=956

- Determann L. Healthy data protection. Mich Telecom Tech L Rev. 2020; 26(2): 229-278. https://repository.law.umich.edu/mtlr/vol26/iss2/3?utm_source=repository.law.umich.edu%2Fmtlr%2Fvol26%2Fiss2%2F3&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages

- Salami E. Artificial Intelligence (AI,) Big Data and the protection of personal data in medical practice. Eur Pharm Law Rev. 2019[Cited 2023 Oct 10]; 3(4):165-175. Available from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3600752

- Koenderman J. Discrimination and privacy concerns at the intersection of healthcare and big data. Cardozo Law Rev. 2020[Cited 2023 Oct 10]; 41(5):2117-2160. https://cardozolawreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/7.-Koenderman.41.5.7.FINAL1-1.pdf

- Rajaretnam T. Data mining and data matching: Regulatory and ethical considerations relating to privacy and confidentiality in medical data. J Int Commer Law Technol. 2014 Jan; 9(4):294-310.

- Ministry of Law and Justice, Govt of India. The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019. Bill No. 373 0f 2019[Cited 2023 Oct 10]. Available from: http://164.100.47.4/BillsTexts/LSBillTexts/Asintroduced/373_2019_LS_Eng.pdf

- Ministry of Law and Justice, Govt of India. The Information Technology Act 2000. Act No. 21 0f 2000. 2000 Oct 17[Cited 2023 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/13116/1/it_act_2000_updated.pdf

- Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, Govt of India. The Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011. 2011 Apr 13[Cited 2023 Oct 10], Available from: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/114407484/

- Joint Committee on The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019. The Data Protection Bill 2021, December 2021 [Cited 2023 Oct 10] Available from: https://eparlib.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/835465/1/17_Joint_Committee_on_the_Personal_Data_Protection_Bill_2019_1.pdf

- Ministry of Law and Justice, Govt of India. The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023. 2023 Aug 11[Cited 2023 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.meity.gov.in/writereaddata/files/Digital%20Personal%20Data%20Protection%20Act%202023.pdf

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt of India. Digital Information Security in Healthcare Act. 2018 March 21[Cited 2023 Oct 10]. Available from: https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/R_4179_1521627488625_0.pdf

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt of India. Draft Health Data Management Policy, April 2022 Version 02 [Cited 2023 Oct 10]. Available from: https://abdm.gov.in:8081/uploads/Draft_HDM_Policy_April2022_e38c82eee5.pdf