RESEARCH ARTICLE

Using case-based role-play to learn professionalism in Pharmacology

Rohini Ann Mathew, Aniket Kumar, Premila M Wilfred, Margaret Shanthi

Published online first on December 20, 2024. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2024.086Abstract

Background: Professionalism has been identified as a key competency for physicians to conduct, effective and ethical practice. The current competency-based medical education curriculum lays great emphasis on the development of attitude, ethics, and communication (AETCOM) among medical students which is embedded in the core concepts of professionalism. Comprehending these concepts early in the course of medical training is especially important as such a change may lead to reducing future incidents of professional misconduct. However, teaching this complex topic to undergraduate students through routine didactic lectures alone is challenging.

Methods: To address this, we divided the batch of second-year MBBS students into 5 random groups and assigned 1 case scenario for role play to each group with sub-questions for discussion and reflection. After a short introductory lecture on professionalism, each group presented their role-play and discussed the sub-questions. Assessment for the improvement in knowledge was done using pre and post-test multiple choice questions.

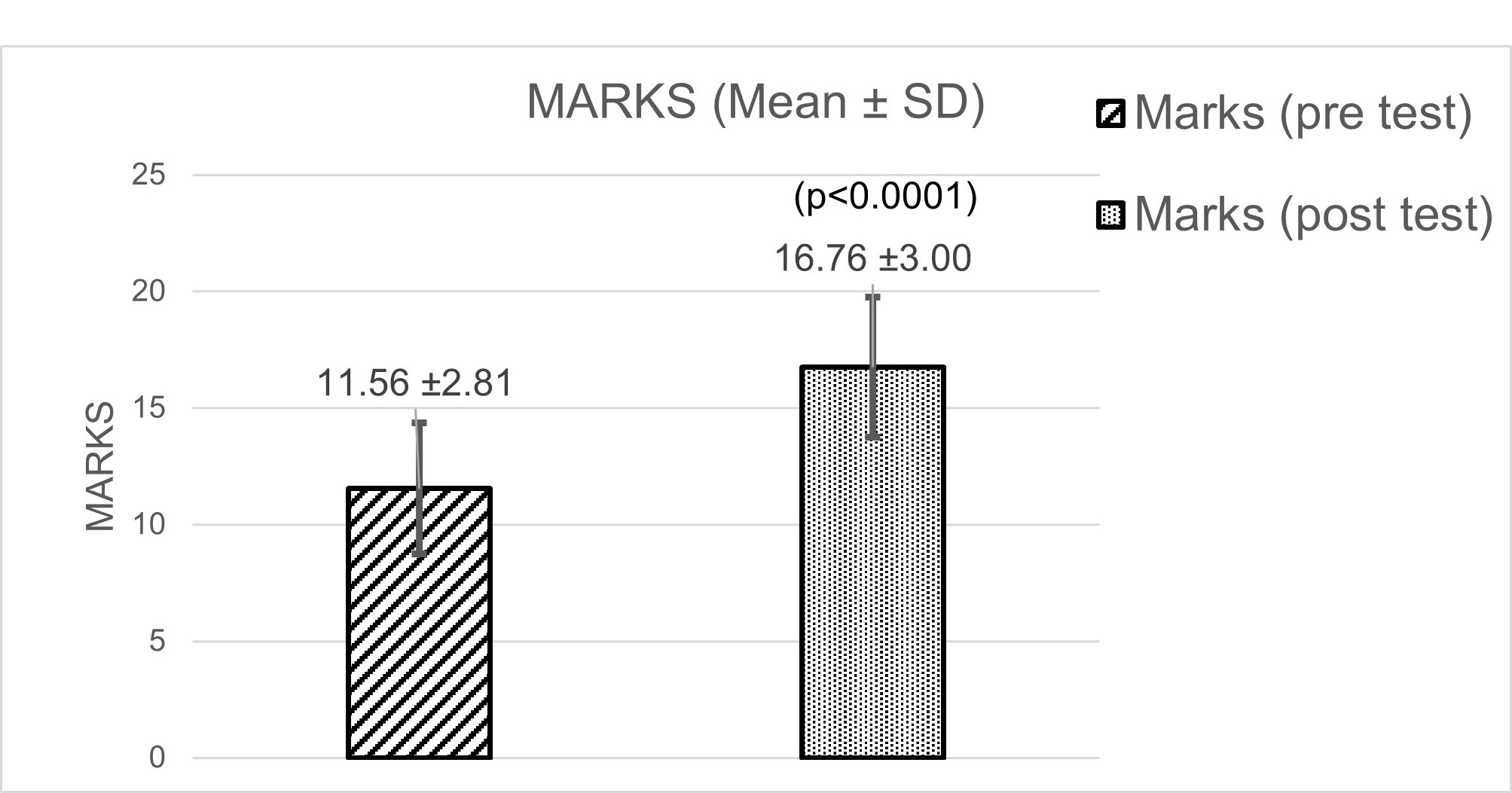

Results: Our findings show a statistically significant improvement in the mean (± Standard Deviation) scores for post-test (16.76±3.00) vs the pre-test (11.56±2.81) (p<0.0001). Participant feedback was overwhelmingly positive based on the 5-point Likert scale.

Conclusion: This shows that an interactive and engaging model, such as relevant case scenarios and role-play with reflection, along with assessment and feedback, could be effective for medical students, in learning the complex topic of professionalism.

Keywords: professionalism, competency-based medical education, attitude, ethics, and communication, medical students, case scenarios, role-play, multiple choice questions, feedback.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increasing emphasis on medical professionalism in medical undergraduate and post-graduate curricula [1, 2]. Professionalism is a dynamic, and evolving concept that finds its true meaning within the core virtues of an individual, such as respect for self and others, compassion, self-awareness, honesty, integrity, accountability, and a commitment to continuous improvement and self-regulation [3]. Teaching the cognitive base of professionalism and providing opportunities for the internalisation of its values and behaviours are the cornerstones of an organisation for teaching professionalism at any level [4].

Broadly speaking, professionalism is essential for safe, effective, and ethical practice in any system. In the context of the healthcare system per se, it means prioritising the welfare and well-being of the patient above all else in any given situation. The competency-based medical education (CBME) module, under the National Medical Commission (NMC) was implemented in India with the 2019-20 MBBS batch to produce a competent batch of ethical Indian medical graduates [5]. This CBME module lays great emphasis on the development of attitude, ethics, and communication (AETCOM) among medical students so they are not found lacking in the soft skills related to effective communication, doctor–patient relationship, ethics, and professionalism [3, 6].

It is a well-known fact that forming habits starts early, and there is a recognised association between professional lapses within the course of medical training in colleges and future incidents of professional misconduct and subsequent disciplinary action by medical boards [7]. Professionalism should be inculcated at the early stages of medical training to prevent malpractice and harm to the patients and to pre-empt having to take punitive action against doctors who are proven guilty. Professionalism, being a matter of attitude, is linked to the “affective domain” that can be moulded only during the formative, impressionable years of medical education [6]. The importance of professionalism in the Indian context cannot be overemphasized. Since time immemorial, Indians have regarded doctors in high esteem, sometimes akin to “God”. However, lately this opinion has been changing due to growing unethical practices among members of the medical fraternity. Frequent media reports of disputes among medical teachers, doctors, and patients are becoming a disturbing trend. The result is for everyone to see, especially in terms of an increase in the incidence of assaults against doctors and hospital property. Doctors are being increasingly looked upon as money-minded, with their decisions and actions being increasingly criticised by the general public [8].

Thus, teaching professionalism early in the pre-clinical phase of undergraduate training could inculcate essential morals, qualities, and convictions in medical students, positively impacting future behaviours and outcomes [7]. It must be noted that formal training in professionalism and medical ethics that emphasises humanistic aspects and standards of conduct, respectively, are as essential as the biomedical aspects of medical education. Unfortunately, till now the teaching of medical professionalism has remained minimal and most medical students acquire it unintentionally. With the recent introduction of the AETCOM module and Code of Medical Ethics in the curriculum there is a ray of hope of moulding a more ethical and professional Indian Medical Graduate [9]. It is therefore imperative that medical education be supplemented by the teaching of professionalism.

However, the data on professionalism among Indian medical graduates is sparse, and there is no standard instructional strategy available to probe the understanding of professionalism in a cohesive, structured, and interactive manner [10]. It must also be kept in mind that although most medical colleges include some form of ethical and professional training, a systematic evaluation of any significant impact of such training among the students’ needs to be done [11]. The multi-dimensional nature of medical professionalism makes it challenging for medical educators to develop and use appropriate instruments to teach and assess professionalism among the target population [12]. Thus, we constantly strive to improve the quality of teaching professionalism [13], by trying out new and innovative methods to make the students understand the core concepts more effectively and efficiently. “To pretend to be a particular character and to behave and react in the way that character would” [14] is the definition of a role-play. Role play has been shown to be an effective and innovative learning tool among students that helps them retain the knowledge they acquire for the longer term [15]. Role-play is also widely used as an educational method for learning and improving communication skills [16], which is the need of the hour.

Towards determining the above, under the AETCOM module, an exercise was conducted among the 2nd year medical students attending Pharmacology classes, where they were presented with relevant case scenarios, using an interactive role-play model, and further evaluated with tests and feedback. The case scenarios were based on real life situations that we have observed medical students in the country face over the years, such as ragging, cheating, indiscipline, unaddressed mental health issues, not owning up to their mistakes at the professional front and the ever-rising trend of social media use and misuse. We believed that this method of learning would allow the students to have a deeper understanding of these common issues and thus, be better equipped to deal with them appropriately and professionally, as and when the need arises.

Our study objectives were to introduce the topic of professionalism to 2nd year medical students using relevant case scenarios and role play and to evaluate the impact of the session on improving the knowledge about professionalism using multiple choice questions (MCQs) and feedback.

Methods

Study designThis was a type of quasi-experimental activity which was carried out among the entire batch of 2nd year MBBS students attending Pharmacology in 2023 in our institution

Ethical considerationsThis session was conducted as a part of the regular academic activities for the batch under the CBME curriculum (AETCOM module) after obtaining the letter of approval from the Principal, and Institutional Review Board (IRB) permitted a waiver of individual consent due to the same. The students were also clearly informed regarding the teaching-learning activity and plans for future publication of the results if needed. Their anonymity was maintained as no specific personal details were collected. The study was approved by the IRB of Christian Medical College, Vellore. IRB Min. No. 15560 dated 26.07.2023.

Sample size calculationOne of the objectives of the study was to assess the impact of the session on improving the knowledge of students about professionalism. Based on a similar study by Mianehsaz et al published in 2023 [17], which had reported the pre-and post-average knowledge scores as 4(1) and 3.75(0.63) respectively. With 80% power, 5% alpha, and a two-sided test, this study required a total of 85 students. However, we studied the entire current batch of 102 students.

Cases and preparationTo initiate the preparations for this study, a discussion was held among faculty members, a few months before the session and during the course of that period, five elaborate case scenarios relevant to medical students were scripted. Each case scenario was prepared keeping in mind common but ethically complex situations that medical students may face during the course of their training and hence discussion on them would be best suited for these students to better understand a few essential aspects of the complex topic of professionalism.

These case scenarios were validated by the department faculty and were as follows:

Case 1 : Social media use.

Case 2 : Repeated small acts of defiance — coming late, not submitting assignments, skipping tests/classes.

Case 3 : Making others complete your record book/ assignments/ bullying.

Case 4 : Revealing medical error to a supervisor / admitting your mistake.

Case 5 : Copying in tests/exams.

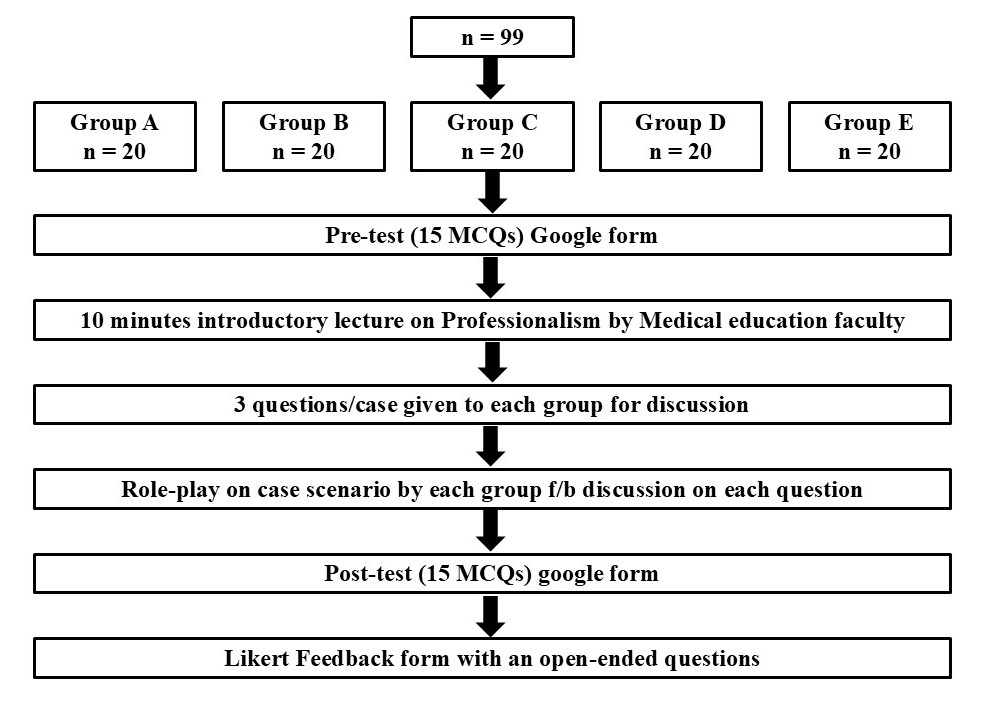

The entire batch was divided randomly using computer-generated random numbers into five groups (A to E) of 20 students each. Each group was given one case scenario for preparation of the role-play, a week in advance. To ensure uniform and effective participation from all students, three sub-questions were additionally formulated for each case. These sub-questions were framed to allow the students an opportunity to express their personal opinions regarding the scenario and to encourage any conflicting viewpoints from other groups during the discussion [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Flowchart of methodology

For assessment of the impact of the session in improving knowledge of professionalism, 15 identical pre- and post-test MCQs were prepared [Table 1]. Each MCQ had one correct response for which appropriate marks were allotted. These MCQs were prepared after being validated by the senior faculty members of the Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacology. For data analysis, a paired t-test using Microsoft Excel was used. The data has been represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) with a p-value of ≤ 0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

The feedback form consisted of 13 questions including one open-ended question to encourage any other comments or suggestions about the session by the medical students. Anonymity was maintained as no personal questions were asked. The questions were based on the 5-point Likert scale.

Table 1. Pre/Post-test questionnaire

|

S.No |

Question |

Option A |

Option B |

Option C |

Option D |

|

1. |

A student must always be aware of demonstrating good conduct when they are: |

In practice |

At the medical college/hospital |

In personal life |

All of these |

|

2. |

The most common reason for referring a doctor to the National Medical Council is due to: |

Lack of competence

|

Misconduct |

Poor health |

Criminal behaviour |

|

3. |

As a medical student, if you accept a delegated activity, |

Your senior or Head of the Department still holds overall accountability. |

You are now accountable for your actions, omissions, or decisions. |

Both of the above. |

None of the above. |

|

4. |

You have seen a patient a few times in the clinic and you both share a lot of common interests. That person sends you a friend request on social media. Should you: |

Accept their request and have a good look at their profile to see what else we have in common.

|

Accept their request, as it might seem rude to ignore it. But to maintain some professional boundaries you will limit them from seeing most of your profile and activity. |

Ignore the request. When you see them next, you will thank them but politely explain that you cannot accept the request due to professional obligations. |

None of the above. |

|

5. |

If you do what's right regardless of who's around, you have the characteristics of: |

Power |

Confidence |

Honesty |

Confidentiality |

|

6. |

Do you think that content about an individual/patient uploaded anonymously on social media: |

It can be traced back to its point of origin. |

It cannot be traced back to its point of origin. |

It does not affect the individual who is being spoken about/discussed in any way. |

Is ethically acceptable? |

|

7. |

Approximately how many (percentage) of students in schools and colleges across the world are subjected to some form of physical violence? |

5-10% |

10-20% |

20-30% |

30-40% |

|

8. |

Making a minor medical (diagnostic /treatment) error that has not been picked up by your superior should be: |

Can be left undisclosed as it has not caused any harm to the patient.

|

Must be informed to your superior immediately |

Must be disclosed to your superior only if that mistake had caused some harm or adverse effect to the patient. |

My reaction will depend on how strict my superior is. |

|

9. |

According to you, cheating in a test or exam; |

Is unacceptable no matter what the situation. |

Is acceptable as long as I don’t get caught. |

Is acceptable as long as it is once in a while, especially if I couldn’t study due to some extracurricular event in college. |

Is acceptable only if I am short of the required minimum marks in my internal assessment to qualify for the final exams. |

|

10. |

Public displays of anger like shouting out loud or throwing stuff over a disagreement with your friend/colleague is: |

Not acceptable under any situation.

|

Acceptable as we have the right to express our frustrations |

Acceptable only if we do it in a place that is not frequented by many people |

Acceptable because the other person is in disagreement with you. |

|

11. |

How prevalent do you think are poor mental health issues in youngsters between 15-24 years in India? |

One in 85 youngsters

|

One in 7 youngsters |

One in 50 youngsters |

One in 22 youngsters |

|

12. |

You come across a patient whose diagnosis has you perplexed. You decide to use the power of social media to your advantage and post details of the patient including his relevant investigations and imaging on a social media platform to get suggestions from other colleagues in your profession regarding the probable diagnosis. Is this: |

Ethically and morally acceptable as long as no personal details that can be used to identify the patient are posted online.

|

Ethically and morally unacceptable even if no personal details used to identify the patient are posted online. |

Is always wrong to discuss anything about any patient over social media. |

Ethically and morally acceptable as long as no personal details are revealed and it is a discussion among medical professionals on a forum with the intention of helping the patient |

|

13. |

If you see that your batchmate is cheating in a test/exam, what will you be inclined to do? |

Ignore him/her as you have your test to worry about

|

Get angry that he/she is openly cheating and none of the invigilators are noticing it |

Discreetly bring it to the notice of one of the invigilators |

Speak to that person after the test, telling him/her that what they did was wrong. |

|

14. |

If I start feeling low/depressed or I start having anxious thoughts regularly due to my studies, I will: |

Keep them to myself as I do not like sharing my issues with others.

|

Start making a big show about it to gain the attention of friends and faculty. |

Talk with one or 2 close friends so that I can feel better. |

Approach someone in the faculty for advice on how to handle stress |

|

15. |

If my parents forced me to join a Medical College, I would respond by: |

Being angry and frustrated with them always

|

By bunking as many classes and tests as I possibly can to show my lack of interest |

Resign myself to my fate, get dejected and somehow get through the years of the medical course. |

Accept their decision and realize that not everyone gets the privilege to become a doctor. |

Implementation and data collection

On the day of the session, first, a pre-test questionnaire was administered to the students. This was followed by a short 10-minute lecture given by a faculty member from the Department of Medical Education to introduce the topic of professionalism to the students. Following the lecture, each of the five groups (A to E) were given the three sub-questions to discuss within their groups for 20 minutes. Each group had a faculty member as moderator. The role of the moderator was clearly defined prior to conducting the session. Each moderator facilitated the smooth flow of the discussion, encouraging the students to actively participate and express their own opinions and ideas regarding the given case scenario. However, the moderator did not influence the discussion in any other way and did not enforce any personal opinions or judgements. Following the discussion, each group came forward to present their role-play. The students enacted the role-play in accordance with the script given. They also brought props and a few of them had costumes to enact their parts. The collective role-play not only encouraged the students to work as a team but also made the entire session enjoyable and interactive, without undermining the true purpose of learning a few core concepts of professionalism. At the end of the play, each group presented their responses to the sub-questions to the rest of the batch.

The floor was opened for anyone to offer supportive or contradictory viewpoints. The same was followed for all the groups. The entire session lasted for three hours. This was followed by a post-test questionnaire. The session concluded after obtaining feedback from the students. Although no written feedback was obtained from the faculty members, the final consensus expressed verbally was that the moderators were satisfied with the participation of the students. They acknowledged that a majority of the students demonstrated an active thinking process, boldly discussed supporting and contrasting views to the sub-questions and enjoyed the whole process of preparation and subsequent enactment of the role-play.

Results and discussion

Of the batch of 102 MBBS students, three students were absent for the session. Within the batch there was an equal male to female ratio with the majority of the students belonging to South India, and between 19 and 23 years old. No other personal details were collected in order to maintain anonymity. Thus, 99 students, five faculty and four postgraduate students took part in this three-hour session. Below we present a summary of each case scenario and case-by-case reflections by each group of students.

Case 1: Social media useThis case was about two medical students from the third year who shared a common social media group with other medical students where they would circulate interesting stories about patients and staff. This social media group was created by Student 1 for this reason specifically. On one such occasion, Student 2 posted a picture with a funny story about a particular patient in the group which was widely circulated and subsequently brought to the notice of the authorities of the medical college. After a few sessions of probing and counselling, Student 1 continued to deny their responsibility for starting a group for sharing confidential patient information in jest on a social media platform and blamed Student 2 for the incident. Student 2 on the other hand understood their mistake and was mortified by it. The college authorities suspended Student 1 for 6 months but let off, Student 2 with a strict warning and with the instruction to write their reflections on the events.

The sub-questions for reflection were as follows:

1. What are your thoughts regarding what the students did?

2. Do you think the committee’s decision to suspend Student 1 was justified?

3. Do you feel Student 2 was let off too easily or was it the right decision to make?

The students reflected on the sub-questions and concluded that both students did not do the ethical thing by sharing personal details about a patient on a social media platform just to present a “funny story”. They also accepted that indulging in such acts brings disrepute to the medical institution involved, the medical profession as such, and impinges on the trust the patient has in the doctor. This is supported by a recent study by Slade et al [18] that suggests that students of the healthcare profession struggle with blurred boundaries between personal and professional online presence, especially related to social media with some of these students demonstrating unprofessional behaviours online.

During the discussion, the students identified each patient’s right to confidentiality and understood that leaks of personal information online can easily be traced back to its source invoking serious repercussions. This act could also be seen as a violation of patient-doctor confidentiality and could land the concerned doctor in serious legal trouble. In conclusion, most of the students felt that the punishment for Student 1 was justified due to their adamant refusal to accept responsibility for their part in this fiasco. Some felt that despite being truly sorry, Student 2 could have been suspended as well, albeit for a shorter duration, as this may serve as a reminder to everyone that it is unethical to share confidential patient details.

Case 2: Repeated small acts of defiance — coming late, not submitting assignments, skipping tests/classes.This scenario presented the story of a first-year medical student studying at a reputed college who was smart and loved participating in extra-curricular activities. This student wanted to become a teacher but the parents insisted on their taking up medicine. After joining the medical college, the student soon lost interest in academics, became bitter towards the parents and started showing defiance by skipping classes, tests and other academic activities. This started to affect the student’s group mates who began to lose marks due to the students’ absence and non-participation in assignments. They decided to lodge a formal complaint following which the student was asked to meet the Principal with the parents to further discuss this issue.

The sub-questions for reflection were as follows:

1. Was the student right to behave in the above way? Rationalise.

2. If you were in this student’s place, what could you have done differently?

3. If you had a friend/colleague like this student, how would you handle them?

The students reflected on the sub-questions and felt that even though they could sympathise with what this student was going through, they did not condone their actions which had started to affect other individuals who had no role to play in this misdemeanour.

Such a scenario is not uncommon in the current era. A study revealed that as medical students progress through their medical education, up to three-quarters of them become progressively pessimistic about academic life and the medical profession [19]. Another study published by Sattar et al [20] showed that the attributes of medical professionalism deteriorate as mental well-being issues grow among the students which can harm the medical students’ overall health, learning abilities and future attitudes towards their patients.

On further reflection, the students felt that if they had been in this students’ place, they would have handled things differently and spoken to their parents or teachers about what they were feeling, asking for their advice regarding how to find a solution. They agreed that if they had a friend in the same situation, they would provide moral support and encourage them to meet with an approachable faculty or counsellor to better handle their emotional turmoil. In conclusion, the students understood that it is important to express negative emotions in the right way and not in a way that might create difficulties for others.

Case 3: Making others complete your record book/assignments/bullyingThis scenario dealt with a final-year medical student who belonged to an affluent family and joined the medical college with the idea of earning a lot of money rather than interest in serving the community. This student was a dominating personality and would often bully juniors into completing personal assignments and record books. This went on for a few years till on one fateful day, one of the juniors refused to be bullied by the student anymore and decided to lodge a formal complaint. This angered the student enough to take a cricket bat and hit the junior on the head causing serious injuries to that junior. A formal complaint was registered against this student with the Medical College authorities as well as the local police. The college suspended the student who is now awaiting trial at the local court with their entire future hanging in the balance.

The sub-questions for reflection were as follows:

1. Could this incident have been prevented in some way? Discuss.

2. If you had an encounter with a person like this student, how would you handle them?

3. Is this student’s fate sealed? How can one (as an individual, as an institution, and as a society) help an individual like this before it is too late?

The students reflected on the sub-questions and felt that maybe this incident could have been prevented if someone had complained about this student in the beginning, as it would have not allowed this student to become so confident in bullying without consequences over the years. The students suggested that if they encounter a similar person, either they would not retaliate or they would complain anonymously to the authorities regarding their actions. Most of the students were aware of the anti-ragging rules instituted in all medical colleges in India and the punishment they entail. Regarding whether a person like this student can be “saved” from such a fate, some students responded that most bullies are not born but created via the “cycle of abuse” [21] and several of them have emotional and mental issues they are unable to deal with on their own, so by providing help at the right time, the course of their future may be altered before it is too late.

This scenario was prepared keeping in mind the rampant mistreatment of medical students worldwide. In 1990, The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) was the first to publish a landmark study observing the incidence, severity and significance of abuse of medical students in the United States [22]. This anonymous cross-sectional questionnaire from 431 respondents revealed that 46.4% of all respondents had been abused at some time in medical school, with 80.6% of seniors reporting being abused during their senior year. More than two-thirds (69.1%) of those abused reported that at least one of those episodes was of “major importance and very upsetting”. Half (49.6%) of the students indicated that the most serious episode of abuse affected them adversely for a month or more; 16.2% said that it would “always affect them”. Mistreatment of medical students is a highly relevant issue which has tangible consequences on their mental and physical well-being, as well as for society at large due to the implications on the quality of patient care [23]. Thus, the students must be made aware of institutional anti-ragging policies, grievance committees, “confidential” complaint avenues and counselling programs to deal with these issues as they arise.

Case 4: Revealing medical error to a supervisor/admitting to your mistakeThis scenario deals with a third-year medical student at a reputed medical college and hospital in the city who is hardworking and well-behaved. In their current clinical posting, this student is assigned to take care of five patients in the medical ward. Their daily routine involves taking rounds for the patients at 7 am, updating the clinician on-call about the patients, sending relevant investigations and ensuring that the right drug and dose are given to the patient. On the day of the event, after finishing the ward work, as the student was leaving the ward, one of the patients started to experience a seizure. This patient was a case of chronic liver disease admitted for control of hematemesis. After the patient was stabilised, the student looked at the patient’s chart and realised that by mistake this patient was administered an intravenous dose of Regular Insulin that was meant for the diabetic patient on the next bed instead of an intravenous dose of Pantoprazole, an acid suppressor. The student realised their mistake but was too fearful to inform the senior physician on call.

The sub-questions for reflection were as follows:

1. Discuss the mistake this student made and how they decided to deal with it.

2. What would you have done if you were in this student’s place?

3. How would you respond if you found your colleague had made a mistake like this? Would you report it to the higher authorities or not?

The students reflected on the sub-questions and concluded that this was a mistake on the part of the student which could have had serious consequences for the patient and thus, it should have been reported to the senior physician on call. They realised that making mistakes is a part and parcel of learning but owning up to those mistakes is important for character building and becoming ethical professionals. However, some of them also admitted that they might be tempted to do what this student did especially if the senior physician on call was a strict person. Reflecting on if their friend was involved in the same situation, most students agreed that they would advise their friend to disclose the incident to the authorities instead of going behind their back and complaining.

The significance of this scenario lies in making medical students understand that reporting errors is fundamental to error prevention and is ethically necessary. The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System was centred on the suggestion that preventable adverse events in hospitals were a leading cause of death in the United States [24]. Also, non-disclosure of a medical error disrespects a patient’s autonomy and violates the ethical principles of beneficence (doing good), nonmaleficence (preventing harm), honesty and integrity [25]. These ethical principles inculcate the importance of transparency and also shape caring, professional doctors who act in the best interests of the patients.

Case 5: Copying in tests/examsThis scenario presents the story of a second-year medical student who was an excellent sportsperson but weak in academics. This student had borderline internal assessment marks as well. The following week there was an important internal assessment test in Pharmacology. On the day of the test, this student realised that he did not know the answers to most of the questions due to inadequate preparation and became petrified about failing again. On the other hand, this student’s good friend had already started answering ardently. Feeling desperate, this student decided to discreetly ask the friend for help. While carefully keeping an eye out for the invigilators, the friend started passing out small notes with the answers written inside. Soon the invigilator caught both of them and sent them to meet with the Head of the Department (HOD) for further action. The friend was indignant and refused to admit to a fault as they were very well prepared for the test. The student on the other hand was feeling ashamed and remorseful as the friend was being punished as well. The HOD decided to leave their papers unmarked and sent them away with a strict warning.

The sub-questions for reflection were as follows:

1. What is your personal opinion on cheating in a test or exam?

2. How would you feel if you were in the friend’s situation? Do you feel the friend was dealt a tough hand?

3. What according to you should be the punishment for cheating in an exam?

The students reflected on the sub-questions and committed that cheating is something several of them have done even though they know it is wrong. However, the fear of failing tempts them to cheat. Some of them felt that one who knows the answers and is helping out a friend should not be punished for cheating. However, most felt that the friend was not treated unfairly by the HOD as what they did also constituted cheating. For the third question, most students felt that leaving the paper unmarked was sufficient punishment for cheating. Post this discussion, the students were informed about the various punishments for cheating under the University statutes for enforcement of discipline in examinations which includes being barred from the current and subsequent exams if caught talking, passing notes, using electronic devices or using any other unfair means [26].

This scenario throws light on one of the most commonly encountered unprofessional actions among medical students. Cheating is a form of violation of academic integrity and although it is attractive or tempting, in the most fundamental sense, it is morally wrongful behaviour [27]. A study from the American Midwest done on 626 nursing students found a correlation between academic cheating and professional misconduct, thus emphasising the need to proactively implement and improve efforts to prevent cheating [28] . At the end of the case discussion, all the students agreed that cheating should be discouraged as it is morally wrong and can lead to serious consequences at both personal and professional levels.

Pre vs post-test analysisThe participants’ pre-test vs post-test marks were analysed using a paired t-test and showed a statistically significant difference (p<0.0001) between the pre (11.56+2.81) and post-test (16.76+3.00) mean scores. This shows a significant improvement in the knowledge scores post-intervention [Figure 2]. A similar result was also seen in a study done by Mianehsaz et al [15] from Iran. They used a similar methodology of case scenarios and role play in teaching professionalism where the mean scores of the participants’ knowledge in the post-test were significantly higher than those in the pre-test (P = 0.042, t = -2.074).

Figure 2. Pre- vs post-test marks

A total of 97 students gave feedback based on the 5-point Likert scale with the responses ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. For the purpose of analysis, they were clubbed into the following three groups, “strongly agree” and “agree” as one group, “neither agree nor disagree” as another group and “disagree” and “strongly disagree” as the third group. The results were evaluated using a simple percentage method. A majority of the students (83, 85%) agreed that with the introduction of the CBME curriculum, teaching the concepts of medical professionalism is essential and innovative methods such as enacting a role play are better for understanding professionalism. Of the 97 students, 86 (88%) felt that after the session, their understanding of the key values of professionalism, and their perspectives on how they must behave professionally have improved considerably. Totally, 76 (78%) students said they actively shared their personal understanding and knowledge during the team discussions and provided instructive feedback to their teammates during preparation for the role-play and team discussions. A majority of the students (87, 89%) said that the case scenarios were realistic, and relevant and helped them to understand how to handle the given situations better, while 85 (87%) students agreed that they would like similar sessions in the future as well. Finally, 61 (62%) students felt that lectures alone were not the best way to teach professionalism

Several students gave promising feedback in our open-ended question, with some of the comments being as follows:

It was a very innovative idea to make us enact, this made us interested in the subject. We also did some active thinking today.

The sessions were useful and made us understand how a medical student should behave and conduct ethically.

It was a very insightful experience. Please have these sessions for the upcoming batches as well.

The session was fun, and interactive and gave me a better understanding of professionalism.

Role-plays are nice ways of sending a message to the students.

Teaching professionalism is complex, as it requires strategies that explicitly as well as implicitly develop a learner’s knowledge, attitudes, judgement and skills [29] . There is still no consensus about what the term “professionalism” really means. For some, it’s the inherent core beliefs and values within the individual [30], for others a set of behaviours [29] and still others define professionalism as identity formation, an ongoing developmental process [31]. Moreover, there is a paucity of studies from India regarding how best to introduce this complex topic to undergraduate medical students in a way that is acceptable, interactive, and efficient enough to leave a lasting positive impression upon their young, impressionable minds.

Another challenge is the existence of the “hidden curriculum” probably best described as the difference between the values articulated in the classroom and the behaviours modelled in the clinical setting. It relates to the fact that even while a medical institution defines its values, those in it, including the so-called “role models” may at times model unprofessional characteristics thus undermining educational objectives [4, 32]. As Tosteson [33] puts it

We must acknowledge that the most important, indeed the only, thing we have to offer our students is ourselves. Everything else they can read in a book.

A third challenge relates to the evaluation process. As healthcare education involves real-world environments more deeply than any other type of teaching, this obligates the educator to evaluate professional behaviour among students to maintain the integrity of the institution’s dual role as a teaching and a caregiving facility [34] . The dominant framework to evaluate professionalism is behaviour-based [35] which is difficult as it requires that the students be continuously monitored and followed up for prolonged periods which may be practically impossible considering time and manpower limitations. Also, a standardised universally acceptable evaluation system for professionalism is difficult to develop. Among the most widely used tools is the Professionalism Assessment Scale (PAS) in medical students. However, its reliability and validity are affected by subjectivity, cultural differences and limited focus on specific domains of professionalism [36].

Limitations of this studyThis study exercise was confined to second-year medical students and was conducted towards the end of their academic year. Even though the pre and post-test analysis shows an improvement in their knowledge and awareness, no follow-up could be done to see the actual impact of this exercise on their behaviour, decision-making skills and attitudes when faced with some of the situations they enacted in the role-plays. We also acknowledge that professionalism cannot be taught in a day. It is a continuous process that involves a repetitive reminder of its many components throughout the years of medical training. Thus, it will be crucial to see how such sessions can be implemented across the years of undergraduate medical education with the hope of creating ethically sound and professional medical graduates.

Conclusion

Medical education must lay the foundation for teaching and evaluating professionalism, to ensure that the students understand the very nature of professionalism and its obligations, and internalise the value system of the medical profession [37]. Lapses in medical professionalism have been associated with numerous lawsuits and defamation cases based on professional misconduct and unethical behaviour among the medical fraternity [38]. There is an unmet need to improve knowledge and awareness about medical professionalism among medical students as early as possible to improve their attitudes, behaviours and decision-making skills.

Although ethical training is carried out in most medical colleges, there is no single standard effective method for teaching this difficult topic to the students. Through this exercise, we have attempted to introduce a complex topic in a simpler way that involves active thinking and participation from the students. Also, the case scenarios prepared for discussion could apply to most medical students across the country irrespective of their backgrounds, thus making these findings generalisable. The overwhelming positive feedback and the significant improvement in the post-test scores shows that our method is effective in creating awareness and improving the knowledge and understanding of medical professionalism among the young minds of the 2nd year medical students.

Rohini Ann Mathew (corresponding author — [email protected], https://orcid.org/0009-0009-9431-963X), Assistant Professor; Aniket Kumar ([email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3260-3239), Associate Professor; Premila M Wilfred ([email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0211-2834), Assistant Professor; Margaret Shanthi ([email protected]), Professor, Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, INDIA

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the batch of 2021 MBBS and all the faculty of the Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, for their involvement and active participation in this activity. A special mention to our senior professor, Dr Jacob Peedicayil for his valuable input and suggestions towards the study paper.

Conflict of interests: None declared.

Funding: This study was funded by the Christian Medical College Fluid Research Fund.

Data sharing: Data not made available in public domain. Please contact corresponding author for access to raw data.

To cite: Mathew RA, Kumar A, Wilfred PM, Shanthi M. Using case-based role- play to learn professionalism in Pharmacology. Indian J Med Ethics. 2025 Apr-Jun; 10(2) NS:128-137. DOI: 10.20529/IJME.2024.086

Published online first: December 20, 2024.

Submission received: February 14, 2024

Submission accepted: July 17, 2024

Manuscript Editor: Vijayaprasad Gopichandran

Peer Reviewers: Ranjith Viswanath, Priyadarshini Chidambaram

Copyright and license

©Indian Journal of Medical Ethics 2025: Open Access and Distributed under the Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits only noncommercial and non-modified sharing in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Al Gahtani HMS, Jahrami HA, Silverman HJ. Perceptions of medical students towards the practice of professionalism at the Arabian Gulf University. BMC Med Educ. 2021 Jan 8;21:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02464-z

- Swick HM, Szenas P, Danoff D, Whitcomb ME. Teaching professionalism in undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 1999 Sep 1;282(9):830–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.9.8303

- Monash University. Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences. [cited 2023 May 19]. Definition of Professionalism. Available from: https://www.monash.edu/medicine/study/student-services/definition-of-professionalism

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Teaching professionalism: general principles. Med Teach. 2006 Jan 1;28(3):205–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590600643653

- Ramanathan R, Shanmugam J, Gopalakrishnan SM, Palanisamy KT, Narayanan S, Ramanathan R, et al. Challenges in the Implementation of Competency-Based Medical Curriculum: Perspectives of Prospective Academicians. Cureus. 2022 Dec 22 ;14(12). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.32838.

- Balachandra V Adkoli, Subhash C Parija. Development of Medical Professionalism: Curriculum Matters. SBV Journal of Basic, Clinical and Applied Health Science. 2020;3(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10082-02243

- Sattar K, Akram A, Ahmad T, Bashir U. Professionalism development of undergraduate medical students. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Mar 5;100(9):e23580. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000023580

- Saurabh SR, Prateek SS. Medical professionalism in India: Present and future. Int J Acad Med. 2018 Dec;4(3):306. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJAM.IJAM_30_18

- Desai MK, Kapadia JD. Medical Professionalism and Ethics. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2022 Jun 1;13(2):113–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0976500X221111448

- Guraya SS, Guraya SY, Doubell FR, Mathew B, Clarke E, Ryan Á, et al. Understanding medical professionalism using express team-based learning; a qualitative case-based study. Med Educ Online. 28(1):2235793. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2023.2235793

- Yadav H, Jegasothy R, Ramakrishnappa S, Mohanraj J, Senan P. Unethical behavior and professionalism among medical students in a private medical university in Malaysia. BMC Med Educ. 2019 Jun 18;19:218. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1662-3

- Li H, Ding N, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Wen D. Assessing medical professionalism: A systematic review of instruments and their measurement properties. PLoS ONE. 2017 May 12;12(5):e0177321. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177321

- Goddard VCT, Brockbank S. Re‐opening Pandora’s box: Who owns professionalism and is it time for a 21st century definition? Med Educ. 2023 Jan;57(1):66–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14862

- Cambridge Dictionary. ROLE-PLAY | English meaning – Cambridge Dictionary. [cited 2023 Dec 16]. Available from: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/role-play

- Loh KY, Kwa SK. An innovative method of teaching clinical therapeutics through role-play. Med Educ. 2009;43(11):1101–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03501.x

- Nestel D, Tierney T. Role-play for medical students learning about communication: Guidelines for maximising benefits. BMC Med Educ. 2007 Mar 2;7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-7-3

- Mianehsaz E, Saber A, Tabatabaee SM, Faghihi A. Teaching Medical Professionalism with a Scenario-based Approach Using Role-Playing and Reflection: A Step towards Promoting Integration of Theory and Practice. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2023 Jan;11(1):42–9. https://doi.org/10.30476/jamp.2022.95605.1651

- Slade C, McCutcheon K, Devlin N, Dalais C, Smeaton K, Slade D, et al. A Scoping Review of eProfessionalism in Healthcare Education Literature. Am J Pharm Educ. 2023 Nov 1;87(11):100124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpe.2023.100124

- A Pilot Study of Medical Student “Abuse”: Student Perceptions of Mistreatment and Misconduct in Medical School | JAMA | JAMA Network. [cited 2023 Dec 5]. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/380398

- Sattar K, Yusoff MSB, Arifin WN, Mohd Yasin MA, Mat Nor MZ. A scoping review on the relationship between mental wellbeing and medical professionalism. Med Educ Online. 28(1):2165892. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2023.2165892

- Major A. To Bully and Be Bullied: Harassment and Mistreatment in Medical Education. AMA J Ethics. 2014 Mar 1;16(3):155–60. https://doi.org/10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.3.fred1-1403

- Silver HK, Glicken AD. Medical Student Abuse: Incidence, Severity, and Significance. JAMA. 1990 Jan 26[cited 2023 Dec 5];263(4):527–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2294324/

- Colenbrander L, Causer L, Haire B. ‘If you can’t make it, you’re not tough enough to do medicine’: a qualitative study of Sydney-based medical students’ experiences of bullying and harassment in clinical settings. BMC Med Educ. 2020 Mar 24;20(1):86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02001-y

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System . Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000 [cited 2023 Dec 5]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK225182/

- Wolf ZR, Hughes RG. Error Reporting and Disclosure. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008 [cited 2023 Dec 5]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2652/

- statutes of the tamil nadu dr mgr university for enforcement of discipline – . [cited 2024 Jan 30]. Available from: https://shorturl.at/nwK7Z

- Academic Integrity and Cheating: Why is it wrong to cheat? [cited 2023 Dec 5]. Available from: https://www.qcc.cuny.edu/socialSciences/ppecorino/Academic-Integrity-cheating.html

- Winrow A, Reitmaier A, Winrow B. Social desirability bias in relation to academic cheating behaviors of nursing students. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2015 Jun 16;5. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v5n8p121

- Lesser CS, Lucey CR, Egener B, Braddock CH, Linas SL, Levinson W. A Behavioral and Systems View of Professionalism. JAMA. 2010 Dec 22;304(24):2732–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1864

- .Lucey C, Souba W. Perspective: The Problem With the Problem of Professionalism. Acad Med. 2010 Jun;85(6):1018. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181dbe51f

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A Schematic Representation of the Professional Identity Formation and Socialization of Medical Students and Residents: A Guide for Medical Educators. Acad Med. 2015 Jun;90(6):718. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700

- Kirk LM. Professionalism in medicine: definitions and considerations for teaching. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2007 Jan;20(1):13–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2007.11928225

- Dc T. Learning in medicine. N Engl J Med 1979 Sep 27 [cited 2023 Dec 4];301(13). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/481463/ https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197909273011304

- University of Mississippi Medical Center. Professionalism Assessment Tool. [cited 2023 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.umc.edu/Research/Centers-and-Institutes/Centers/Center-for-Bioethics-and-Medical-Humanities/CBMH Education/Professionalism-Across-the-Curriculum/Professionalism-Assessment-Tool.html

- Mak-van der Vossen M, van Mook W, van der Burgt S, Kors J, Ket JCF, Croiset G, et al. Descriptors for unprofessional behaviours of medical students: a systematic review and categorisation. BMC Med Educ. 2017 Sep 15;17(1):164. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0997-x

- Tanrıverdi EÇ, Nas MA, Kaşali K, Layık ME, El-Aty AMA. Validity and reliability of the Professionalism Assessment Scale in Turkish medical students. PLOS ONE. 2023 Jan 26;18(1):e0281000. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0300857

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2014 Nov;89(11):1446–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427

- Papadakis MA, Hodgson CS, Teherani A, Kohatsu ND. Unprofessional behavior in medical school is associated with subsequent disciplinary action by a state medical board. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2004 Mar;79(3):244–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200403000-00011