RESEARCH ARTICLE

Knowledge attitude and practice among dentists in Dakshina Kannada, India regarding ethical concerns in extraction of wrong tooth

Athira Purushothaman, Poonam R Naik

Published online first on November 21, 2024. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2024.076Abstract

Background: Truth-telling and autonomy go hand in hand. As a result, it is a breach of the patients’ rights to autonomy when medical errors are not disclosed to them. The aim of this study is to describe knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding ethical considerations among dentists following extraction of the wrong tooth.

Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted among dentists in Dakshina Kannada, India, who have had a minimum experience of 50 extractions in their practice. A validated scenario-based questionnaire was used to collect data and circulated via Google forms forwarded through email or an instant messaging application.

Results: A total of 116 dentists responded to the survey. The majority (83, 71.6%) agreed that extraction of the wrong tooth though unintentional is considered as maleficence or negligence in dental practice. More than 70% participants (85) believed that the patient had the right to be informed about the mishap and deserved compensation for the same, while 38.8% participants agreed that dentists are less likely to be complained against if they disclosed the mishap verbally. Six responses to open ended questions reported that extraction of the wrong tooth had occurred to their knowledge.

Conclusion: The majority of responses in our study appear to indicate that participants embrace the ideals of justice, autonomy, and non-maleficence. This study may have influenced the participants’ attitudes regarding ethical issues related to incorrect tooth extraction and other iatrogenic errors they may encounter in their own or in a colleague’s practice.

Keywords: doctor-patient relation, wrong tooth, ethics, non-maleficence, compensation, extraction

Introduction

Over the past two decades, the doctor-patient relationship has evolved. Awareness of medical as well as dental negligence is growing among the public in India. A higher risk of malpractice exists, particularly in cases involving complex case scenarios, as a result of inadequacy of both medical and dental professionals in updating knowledge in their respective fields [1]. Around the world, there has been ample documentation of violence against nurses, doctors, and other medical staff. Lack of communication skills and professionalism are among the identified factors contributing to such incidents of violence against healthcare professionals [2]. According to Janakiram et al, these may be attributed to the doctor’s paternalistic attitude or lack of empathy [3].

In medical practice, abortion, contraception, professional misconduct, treating a patient with a terminal illness, maintaining a patient’s confidentiality, use of traditional medicine, religion and conflicts of interest are some examples of areas where ethical issues are frequently observed [3]. When essential information is withheld from the patient, the ethical principle of autonomy or respect for decision making is breached. The principle of autonomy or decision making is implemented through the process of informed consent. Informed consent is a prerequisite for any patient treatment, as stated by ethical and legal principles. In order to participate in this process, the patient or their legal representative must be provided with all pertinent facts that may influence their choice of treatment [4].

“To err is human” is a well-known saying. Human beings are fallible and will make mistakes in their lives [5].

General dentists and especially oral and maxillofacial surgeons perform dental extraction on a regular basis. This dental procedure is subject to many complications and errors, one among which is wrong tooth extraction. Wrong tooth extraction is defined as the extraction of a tooth other than the one intended. Erroneous patient positioning or surgical site preparation, inaccurate information from the patient or their family, absence of patient consent, fatigue of the surgeon, multiple surgeons, performing multiple procedures on the same patient, unusual time constraints, emergency procedures, unusual patient anatomy, and general poor communication between the patients, the treating staff, and the patients’ families are risk factors for performing a wrong tooth extraction [6].

Dental ethics comprises professional conduct and rules imposed by members of the dental profession. The Dental Council of India has laid down the dentists’ Code of Ethics regulations in 1976, and it was later amended in 2014. Every registered dentist has a responsibility to read these regulations, understand her/his responsibilities, and follow them [7].

The foundation of the doctor-patient relationship comprises of the principles of autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, justice and fidelity at all times. Autonomy is closely associated with truth telling. Therefore, non-disclosure of medical errors to patients violates the rights of autonomy of the patients. The principle of non-maleficence implies an obligation not to inflict harm on others. “Above all [or first] do no harm.” Furthermore, the failure to disclose the error to the patient complicates the situation. According to the principle of justice, disclosure of error ensures compensation to patients. For instance, in addition to an apology, patients may be owed compensation for increased healthcare costs or lost wages [5].

Withholding the information from patients could pose additional ethical challenges. The public generally extrapolates wrongdoing by trusted professionals to other members of that profession. As a result, the deception, if discovered, will reflect adversely on the entire dental/medical profession [4].

The reasons for non-disclosure of medical errors may be fear of loss of the physician’s reputation and self-esteem. Junior doctors prefer not to disclose medical/ dental errors as they are concerned about their professional advancement, while senior professionals do so to safeguard their authority. In addition, fear of litigation is another deterrent to disclosing errors [8].

Many studies have been conducted to assess knowledge, attitudes and practices among clinicians regarding negligence/mishaps [3, 6, 9]. This is a descriptive cross-sectional study that investigates ethical conduct of dentists after the extraction of a wrong tooth. With regard to an alleged act of negligence, this study may educate dentists or aid them in exploring the relevant bioethical principles.

This study aims to describe the knowledge of ethics and attitude and practice of dentists after an extraction of the wrong tooth.

Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted among dentists over a span of two weeks in the month of November 2021. The study participants included private practitioners and post graduate students in Dakshina Kannada, India, with experience of carrying out at a minimum of 50 dental extractions in their practice.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Yenepoya Dental College- (YEC2/963).

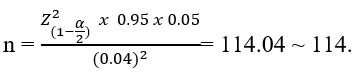

Sample size calculationSample size was calculated based on the study conducted by Al Nomay et al [10]. According to the study, it was found that approximately 94.4% participants preferred that medical errors should be disclosed.

With the available information and considering 5% level of significance and with 4% absolute precision, the minimum number required for a sample size for the present study was:

We utilized the method of snowball sampling by circulating Google Forms among dentists via social media platforms such as WhatsApp groups created by dentists in Dakshin Kannada, while also encouraging them to further distribute the forms among other dentists in Dakshina Kannada. Our outreach resulted in approximately 150 dentists receiving the questionnaire.

Data collection toolThe questionnaire developed for data collection consisted of four parts. Part A included questions that collected details like whether the participant was a practitioner or post graduate student, and experience in terms of number of extractions performed. No name or email id was collected. The questions in Part B, C and D assessed the knowledge, attitudes and practices among dentists regarding ethical conduct following extraction of the wrong tooth. Case scenario-based questions were incorporated in Part C of the questionnaire to assess the ethical principles of truthfulness and non-maleficence among the participants. The questionnaire was validated by five subject experts in Dentistry and Bioethics.

Google forms were created using the questionnaire. The questionnaire was shared with participants through email or instant messaging application along with a participant information sheet. The participants were requested to go through the participant information sheet and were encouraged to contact the principal investigator with any queries. It was stated in the invitation email that if the consented to participate in the study, they could click on the link provided and participate.

Statistical analysisData was entered in Microsoft Excel sheet and data analysis was performed on SPSS Version 23. Descriptive analysis was done wherein qualitative variables were expressed as percentages and proportions and quantitative data as mean and standard deviation. Given the small sample sizes and sparse data (with over 50% of cells having expected counts <5), Fisher's exact test was chosen to assess difference in responses among the respondents towards scenario-based questions.

Results

Of the 150 dentists who received the questionnaire, 116 responded, thus exceeding the determined sample size of 114.

Part AAmong the participants, 52 (44.8%) were post graduate students, 50 (43.1%) were practicing dentists and 14 (12.1%) were currently not working.

A total of 44(37.9 %) participants claimed to have experience of extraction of more than 100 teeth, 18(15.5%) participants had experience of 80-100 extractions, 26(22.4 %) had experience of 60-80 extractions, while 24.1% had experience of 50-60 extractions.

Part BAround 98% of the participants responded that taking informed consent was necessary in dental practice.

A total of 79(66.1%) participants consider autonomy to mean that both patients and doctors can take decisions regarding treatment, of which 39(78%) were practitioners, 30 (57.7%) were PG students and 10 (71.4%) were not working currently. Only 22 (19%) participants responded that the ultimate decision regarding treatment is made by the patient alone (Figure 1, available online only). None of the practitioners responded that the patient is persuaded to accept a treatment decided by the doctor.

A large proportion of participants (72.4%) — 33 (66%) practitioners, 41 (79%) PG students and 10 (71.4%) not working currently believed that the patient has the right to be informed about the mishap and be offered some compensation, while 26.1% of participants including 16 (32%) of practitioners, 11(22.2%) of PG students and 4(29%) of others gave a similar response but believed that compensation is not necessary (Figure 2, available online only).

None of the PG students and those not working responded that doctors should not disclose the error.

When asked to choose examples of alleged negligence from the options given, 71.6 % of the respondents agreed that unintentional extraction of the wrong tooth was considered maleficence or alleged negligence in dental practice. Two open responses were recorded for the option “any other” examples of alleged negligence in dental practices which included laceration of mucosa while scaling, accidental swallowing of instruments, and poorly polished and finished restoration.

Part CAttitude-based questions were asked in Part C accompanied by a scenario (Supplementary file 1). The majority of respondents (95, 81.9%) reported that it was important to inform the patient about a mishap/iatrogenic error and autonomy is affected if the patient is not informed about the mishap. Nearly 71(61.2 %) participants agreed that the mishap though accidental was considered maleficence. Around 45(38.8%) participants agreed that if the dentist discloses his mistake verbally, he is less likely to be complained against, while 37(31.9%) participants were not sure about the statement. Responses to each scenario-based question by each category of respondents are described in Table 1. No significant difference was found among the category of respondents regarding for their responses.

Table 1. Distribution of answers to scenario-based questions

|

|

|||||

|

Type of participants (n) |

Yes n (%) |

No n (%) |

May Be n (%) |

I don’t know n (%) |

p value |

|

Practitioners (50) |

39(78.0) |

0(0) |

11(22.0) |

0(0) |

0.12 |

|

Post graduate students (52) |

44 (84.6) |

0(0) |

6(11.5) |

2(3.9) |

|

|

Currently not working (14) |

12(86.0) |

1(7.0) |

1(7.0) |

0(0) |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Practitioners (50) |

41(82.0) |

1(2.0) |

7(14.0) |

1(2.0) |

0.42 |

|

Post graduate students (52) |

44 (84.6) |

1(1.9) |

5(9.6) |

2(3.9) |

|

|

Currently not working (14) |

10(71.4) |

2(14.3) |

2 (14.3) |

0(0) |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Practitioners (50) |

28(56.0) |

8(16.0) |

13(26.0) |

1(2.0) |

0.21 |

|

Post graduate students (52) |

37 (71.1) |

7(13.5) |

8(15.4) |

0(0) |

|

|

Currently not working (14) |

6(43.0) |

5(36.0) |

3(21.0) |

0(0) |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Practitioners (50) |

19(38.0) |

9(18.0) |

17(34.0) |

5(10.0) |

0.85 |

|

Post graduate students (52) |

21 (40.0) |

11(21.0) |

16(31.0) |

4(8.0) |

|

|

Currently not working (14) |

5(36.0) |

5(36.0) |

4(28.0) |

0(0) |

|

|

Note: Fischer’s Exact Test was done |

|||||

Part D

In practice-based questions, the participants were asked what they would advise Dr. ABC if he/she was their friend (Figure 3, available online only).

None of the group responded that the dentist need not inform the patient and discharge after charging for extraction of two teeth.

Around 39(33.6%) participants responded that there are allegations of negligence by dental practitioners to their knowledge, while 40(34.5%) participants responded that there are no such allegations. Fourteen open-ended responses were obtained, among which 6 responses stated that extraction of a wrong tooth had occurred to their knowledge.

Discussion

This study sought to focus on the ethical conduct of dentists in Dakshina Kannada towards extraction of wrong tooth. Wrong tooth extraction is considered as negligence in dental practice [1]. Totally, 71.6% of the participants agreed that extraction of the wrong tooth, though unintentional, is considered as maleficence or alleged negligence in dental practice.

The principle of autonomy is reflected as the ability of an individual (patient) to make an informed, un-coerced and rational decision [11]. Allowing or enabling patients to make their own decisions about which healthcare interventions they will or will not receive, implies respect for autonomy [12]. Informed consent is based on the concept of autonomy [4]. Approximately 83% and 91% dentists in studies conducted by Guptha A et al in Bangalore and Guptha V et al in Punjab, respectively, accepted that informed consent was necessary in their profession, which was in accordance with the responses in our study [13, 14].

Only 19% of the participants in this study have an opinion that autonomy implies that patients take part in decision making regarding healthcare. More than half the participants, ie 66.1%, believe both patients and doctors can take part in decision making regarding treatment. The physician has the responsibility to provide sufficient information to the patients, to elicit their preferences, while the patient has the ultimate right to decide. This process whereby patients and physicians collaborate to make a decision is called shared decision making [15]. Although Beauchamp and Childress have mentioned that “shared decision making” does not promote the patient’s autonomy [16], they have also made it clear to exclude people who are not “competent” from the protection of the principle of respect for autonomy. The principle of autonomy may not adequately safeguard individuals who are essentially competent but find it difficult to make decisions about their healthcare due to a range of factors, such as lack of confidence, uncertainty about their preferred course of action, competing priorities, or fear of being held accountable in the event of unsatisfactory outcomes. This could occur if clinicians are more likely to offer and authorise choice rather than empower patients to make informed decisions [12]. According to many proponents, shared decision making is the right method to interpret the doctor-patient relationship because it respects patient autonomy in decision making contexts [17]. Ignaas et al found that a relationship between shared decision making and autonomy existed using patients’ perceptions [18]. However, it is still not clear precisely how shared decision making is related to autonomy [19].

According to the principle of autonomy it is the patient’s right to have full information about the treatment [11]. Therefore, the physician is obliged to disclose any error or mistake to patients to respect their autonomy [20] The majority of participants (81.9%) in this study also believe that it is necessary to report to the patient about extraction of the wrong tooth and consider withholding the information as an infringement of the patient’s autonomy. Al Nomay et al also reported 94.4% participants preferred to disclose medical errors in a study conducted among dental professionals and dental auxiliaries in Saudi Arabia, to assess attitudes towards disclosure of medical errors [10]. A systematic review conducted by O’ Connor et al reported that while most physicians supported disclosure, however, in reality many don’t actually disclose errors [8].

While almost all the participants agreed that the patient has the right to be informed about the mishap according to the principle of autonomy, 72.4% responded that offering compensation was also a part of protecting patient’s autonomy. Ensuring compensation represents the ethical principle of justice. Patients may be owed compensation for their loss due to iatrogenic error caused by the physician, according to the principle of justice [6]. Though this reflects inaccurate knowledge of the definition of ethical principles among the participants, their response on providing justice following disclosure of error reveals a better attitude among the participants towards the ethical considerations of an iatrogenic error.

The duty of a physician to act in a way that does not harm a patient is known as nonmaleficence. This ethical concept maintains some moral precepts, including do not murder, inflict pain or suffering, render someone unable, incite hatred, or deny another person the necessities of life [21]. Around 61.2% of participants agree that extraction of the wrong tooth though accidental, violates the principle of non-maleficence.

As stated in review by Goel et al, dentists who are frank and inform the patient about mishaps are less likely to be complained against. Communicating with patients reflects how genuinely concerned the dentists are, which will enhance trust in physician and prevent lawsuits against the hospital [1]. Ironically, while a majority of the participants confirmed that disclosure of error was necessary, only a few participants, amounting to 38.8% believed that the dentist/physician is less likely to be complained against, if they disclosed the mistake or error to the patient. In a review of literature by Mazor et al, the patient feedback was that, if the doctor told them about the error, they were more likely to stay with the doctor, and less likely to report and sue the doctor. Patients responded in focus group discussions, that disclosure would strengthen their confidence and trust in the doctors [22].

An almost similar proportion of participants who agreed that patients should be compensated for their loss due to iatrogenic error (72.4%) (Part B), also reported that they would advise the patient about the best option available for the replacement of the wrongly extracted tooth after informing the patient about the mishap (73.5%) (Part C). This was followed by around 27% of participants, who only agreed to inform the patient about the mishap without offering any compensation. None of the participants responded that they would advise not informing the patient about the mishap, based on the given scenario. This may be attributed to social desirability bias.

Around 33.6% of participants confirmed that they knew of certain allegations of negligence by dental practitioners. Six open-ended responses were obtained about wrong tooth extraction to their knowledge. A review in 2012 by Thusu et al stated that only 2% of wrong tooth extractions were reported [10]. A questionnaire-based study among Nigerian dentists reported a prevalence of 21.1% of wrong tooth extraction [6].

Limitations and strengthsThis study is the first of its kind in India, to describe the knowledge, attitude and practice of dentists regarding ethical issues encountered in wrong tooth extraction.

As several favourable responses were reported among participants, social desirability could be regarded as one of the limitations of the study. As the survey was administered within social media groups — albeit via an online platform that ensured anonymity of personal information — the probability that respondents would be transparent about disclosing information concerning iatrogenic errors was minimal. The nature of convenience (snowball) sampling adds to this. Lack of query of any ethical training of participants and lack of knowledge-based questions on the Consumer Protection Act was another limitation. Enquiry assessing knowledge of the same would have helped to determine how the dentists uphold the law and ethical standards in their practice with vigilance.

This study gives an insight into the dentists’ understanding of bioethical principles and how they might deploy them in situations of alleged negligence or maleficence.

Conclusion

The doctor-patient relationship has an inherent fiduciary nature, and it is based on confidence and trust. Mutual respect and honesty form the essence of this relationship [23]. A majority of responses in this study seem to reflect that participants uphold the principles of non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice. Almost 98% of study participants believed informed consent was necessary in dental practice. Approximately 82% of them agreed that patients have to be informed about any iatrogenic error occurring in the course of their practice, while nearly 73% of them also supported the process of compensation for the patient’s loss. Further studies regarding disclosure of other iatrogenic errors in dentistry, its ethical and legal aspects might complement the findings in this study. Gathering information in this subject and future studies around it may also help in assessing the need to incorporate compulsory bioethics and medical ethics training in both the UG and PG curriculum.

Authors: Athira Purushothaman ([email protected], https://orcid.org/ 0000-0003-4739-787X), Post graduate student, Department of Public Health Dentistry, Yenepoya Dental College; Poonam R Naik (corresponding author — [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8596-7995), Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Yenepoya Medical College; and Faculty of Centre for Ethics, Yenepoya (Deemed to be University), Mangaluru, INDIA.

Conflict of Interest: None to declare. Funding: None.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr Vina Vaswani, Director, Centre for Ethics, Yenepoya (Deemed to be University), Mangaluru as well as the institution for providing a wonderful learning experience and the opportunity to work on this project.

Ethics approval: Institutional Ethics Committee of the Yenepoya Dental College- (YEC2/963).

Data sharing: Data not made available in public domain. Please contact corresponding author for access to raw data.

To cite: Purushothaman A, Naik PR. Knowledge attitude and practice among dentists in Dakshina Kannada, India regarding ethical concerns in extraction of wrong tooth. Indian J Med Ethics. 2025 Jan-Mar; 10(1) NS:34-39. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2024.076

Submission received: January 27, 2023 Submission accepted: March 20, 2024

Published online first: November 21, 2024

Manuscript Editor: Mala Ramanathan

Peer Reviewers: Two anonymous reviewers

Copyright and license

©Indian Journal of Medical Ethics 2024: Open Access and Distributed under the Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits only noncommercial and non-modified sharing in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Goel K, Goel P, Goel S. Negligence and its legal implications for dental professionals: A Review. TMU J Dent.2014 [Cited on 2021 Nov 23];1(3):113-118. Available from: http://tmujdent.co.in/pdf/vol1issue3/06%20TMU_JD_35.pdf

- Chakraborty S, Mashreky SR, Dalal K. Violence against physicians and nurses: a systematic literature review. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2022;30(8):1837-1855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01689-6

- Janakiram C, Gardens SJ. Knowledge, attitudes and practices related to healthcare ethics among medical and dental postgraduate students in south India. Indian J Med Ethics. 2014 Apr 1;11(2):99-104. https://doi.org/10.20529/ijme.2014.025

- ChiodoG,Tolle S, Jerold L. Ethical Case Analysis ; The extraction of wrong tooth. Am J OrthodDentofacialOrthop.1998;114(6):721-723. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70059-9

- Edwin AK. Non-disclosure of medical errors an egregious violation of ethical principles. Ghana Med J. 2009[Cited on 2021 Nov 23];43(1):34-39. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2709172/

- Jan AM, Albenayan R, Aisharkawi D, Jadu FM. The prevalence and causes of wrong tooth extraction. Niger J Clin Pract. 2019;22:1706-14. https://doi.org/10.4103/njcp.njcp_206_19

- Kesavan R, Mary A V, Priyanka M, Reashmi B. Knowledge of dental ethics and jurisprudence among dental practitioners in Chennai, India: A cross-sectional questionnaire study. J OrofacSci. 2016;8:128-34. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.31503

- O’Connor E, Coates HM, Yardley IE, Wu AW. Disclosure of patient safety incidents: a comprehensive review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22(5):371-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzq042

- Thusu S, Panesar S, Bedi R. Patient safety in dentistry – state of play as revealed by a national database of errors. Br Dent J. 2012;213(3):E3. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.669

- Al Nomay SN, Ashi A, Al-Harghan A, Abdulaziz A, Masaudi E. Attitudes of dental professional staff and auxiliaries in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, toward disclosure of medical errors. Saudi Dent J. 2017;29(2):56-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sdentj.2017.01.003

- Ghazal L, Saleem Z, Amlani G. A Medical Error: To Disclose or Not to Disclose. J Clin Res Bioeth. 2014[Cited on 2021 Nov 23];5:2. Available from: https://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fhs_son/67/

- Entwistle VA,Carter SM, McCaffery K. Supporting Patient Autonomy: The Importance of Clinician-patient Relationships. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;25(7):741-745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1292-2

- Gupta A, Purohit A. Perception of Informed Consent among Private Dental Practitioners of Bangalore South – A Kap Study. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res. 2018 [Cited on 2021 Nov 23] ;2(1):2189-2193. Available from: https://biomedres.us/pdfs/BJSTR.MS.ID.000656.pdf

- Gupta VV, Bhat N, Asawa K, Tak M, Bapat S, Chaturvedi P. Knowledge and attitude toward informed consent among private dental practitioners in Bathinda city, Punjab, India. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2015;6(2):73-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrp.2014.12.005

- Wancata ML, Hinshaw DB. Rethinking autonomy: decision making between patient and surgeon in advanced illnesses. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(4):77. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2016.01.36

- Ubel PA, Scherr KA, Fagerlin A. Autonomy: What’s Shared Decision Making Have to Do With It? Am J Bioeth. 2018; 18(2): W11–W12. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2017.1409844

- Lewis J. Does shared decision making respect a patient’s relational autonomy? J Eval Clin Pract. 2019;25(6):1063-1069. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13185

- Devisch I, Dierckx K, Vandevelde D, De Vriendt P, DeveugeleM.Patient’s Perception of Autonomy Support and Shared Decision Making in Physical Therapy. Open J Prev Med. 2015 [Cited on 2021 Nov 23];5:387- 399. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=60018

- Sandman L, Munthe C. Shared decision-making and patient autonomy. Theor Med Bioeth. 2009;30(4): 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-009-9114-4

- Wu AW, Cavanaugh TA, McPhee SJ, Lo B, Micco GP. To tell the truth: ethical and practical issues in disclosing medical mistakes to patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(12):770-5. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07163.x

- Varkey B. Principle of Clinical ethics and their Application to Practice. Med PrincPract. 2021;30:17–28. https://doi.org/10.1159/000509119

- Mazor KM, Simon SR, Gurwitz JH. Communicating With Patients About Medical Errors: A Review of the Literature. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(15):1690–1697. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.15.1690

- Chamberlain CJ, Koniaris LG, Wu AW, Pawlik TM. Disclosure of “Nonharmful” Medical Errors and Other Events: Duty to Disclose. Arch Surg. 2012;147(3):282–286. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2011.1005