RESEARCH ARTICLE

Insurance coverage for mental illness: A review through a lens of bioethics and the MHCA, 2017

Amiti Varma, Nikhil Jain, Sayali Mahashur, Tanya Nicole Fernandes, Arjun Kapoor, Soumitra Pathare

Published online first on November 4, 2024. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2024.072Abstract

Introduction: Health insurance coverage can serve as protection against catastrophic health expenditures. Section 21 (4) of the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 (MHCA) mandates insurance coverage for mental illness to be on par with that for physical illness. Despite this, anecdotal evidence shows persons with mental health conditions are routinely denied or face difficulties in obtaining medical insurance coverage due to their mental illness.

Method: We undertook an analysis of all insurance policy documents published on the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI) webpage for the year 2020-21 to examine their relevance to mental illness and to examine how the policy wording adheres to Section 21 (4) of the MHCA and the core principles of bioethics.

Results: We sourced 459 health insurance policies for the year 2020-21 from the IRDAI webpage. Of these, 268 relevant insurance policies were analysed in depth for their adherence to the MHCA guidelines and principles of bioethics. Of the policies analysed (n=268), we found six policies (from two insurance providers) explicitly excluded mental illness across all domains, in direct contradiction of the MHCA and the subsequent guidance issued by the IRDAI. Most insurance policies excluded coverage for injuries due to attempted suicide or self-injury (n=224) or alcohol consumption/substance use (n=267). Out-patient services were included in 23 policies.

Discussion: Health insurance policies continue to contain discriminatory terms for mental illness thus violating the principle of parity put forth by the MHCA and at odds with core principles of bioethics. Sustained advocacy efforts are required to ensure insurance providers abide by the principles of parity in letter and in spirit to remove differential or discriminatory terms for mental illness in their policies in compliance with Section 21 (4) the MHCA.

Keywords: health insurance, medical insurance, mental health, Mental Healthcare Act, health financing

Introduction

Access to care for individuals living with mental illness is a pressing concern in India. The National Mental Health Survey (NMHS) 2016 reported a 10.6% community prevalence of mental illness and a large treatment gap (55-85%), where individuals do not have access to treatment for mental illness [1]. Beyond access to treatment for conditions with higher prevalence such as bipolar affective disorders and psychotic disorders, etc, researchers describe a “care gap” involving the complex and intersecting dimensions of lack of access to quality treatment for mental illness, in both psychosocial and physical healthcare [2].

According to the National Sample Survey (NSS) 2017-18 (75th Round), the average cost of hospitalisation for psychiatric and neurological ailments was ₹26,843 per year. Public hospitals’ cost of care was reported as ₹7,235, while for private hospitals cost of care was ₹41,239 [3, 4]. Further, estimates showed 59.5% and 32.4% of households had catastrophic healthcare expenditure on mental illness, exceeding 10% and 20% of monthly household consumption expenditure, respectively [5]. Given the high costs of medical procedures and hospitalisation, medical insurance plays a critical role in protecting against catastrophic health expenditures. Although private health insurance is often criticised for its profit-driven model, it covers 20% to 44% of India’s population and remains a key stakeholder in the Indian healthcare system [6, 7]. Given the significance of this, it is imperative that the insurance industry upholds ethical principles and prioritises the best interests of patients [8].

India’s Mental Healthcare Act 2017 (MHCA), taking a rights-based approach, was enacted to comply with its obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) [9, 10]. The Convention explicitly discusses medical insurance under Article 25 [10]. The MHCA, under Section 21 (4) states “Every insurer shall make provision for medical insurance for treatment of mental illness on the same basis as is available for the treatment of physical illness” [9]. Thus, ensuring insurance coverage for mental illness, as mandated by the MHCA, may be regarded as one approach to bridge the care gap for mental illness [2],

Health insurance coverage and the Mental Healthcare ActPersons living with mental illness do not have the same rights in access to insurance in India, where until recently, treatment for mental illnesses were routinely excluded in health insurance policies through standardised exclusion clauses. This held true for both for care for mental illness and for standard physical illnesses, typically accessible to people without a history of mental illness [9, 11, 12]. The principle of parity, as outlined in the CRPD and the MHCA, emphasises that merely including mental illness in healthcare policies is insufficient. Treatment for mental illness must be on par with that for physical illness in terms of availability, accessibility, and quality [13, 14]. Considering this, the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI) issued a circular in 2020 to include mental illness under medical insurance coverage [15].

Notwithstanding the regulatory circular, non-compliance resulted in a landmark judgment by the Delhi High Court in 2021. The 2021 judgment ordered all insurance companies to comply with Section 21 (4) of the MHCA and cover mental illness in health insurance policies without any discrimination [13, 16]. The Court held that there cannot be discrimination between physical and mental illness, and it was the duty of IRDAI to supervise and ensure that the provisions of the MHCA are fully implemented by all the insurance companies for the benefit of persons who obtain health insurance policies [13]. Following the Delhi High Court’s landmark judgment, the Bombay High Court stayed the insurer’s rejection of a policy proposal put forward by a person with bipolar disorder using the former as precedent [17]. These judicial interpretations demonstrate how insurance companies and their representatives are liable to be prosecuted and should be held accountable for violating Section 21 (4) of the MHCA. While securing insurance coverage for mental illness was achieved in the case presented in the Delhi High Court, seeking legal recourse is not feasible for many, given the skills, knowledge, time and monetary resources involved.

Health insurance coverage and the lens of bioethicsBeyond the MHCA, the universally recognised principles of bioethics underscore the importance of fair, equitable, and ethical treatment in healthcare, including mental healthcare. The principles of bioethics namely autonomy, non-maleficence, and beneficence provide a fresh perspective to examine the practices of insurance companies regarding mental healthcare policies through an ethics and equity lens [18].

Despite the revised guidelines of the IRDAI, individuals living with past or current mental illness (as with other pre-existing conditions) continue to face difficulties in securing health insurance coverage in India [11, 12]. Considering that persons living with mental illness are disproportionately predisposed to physical ailments including, but not limited to, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, diabetes and other diseases and infections, this raises concerns around unethical exclusion and disregards the ethical principle of beneficence, that necessitates that providers promote good health for the benefit of their patients or clients [19].

Another core principle of bioethics, non-maleficence, which relates to the ethical duty of insurance providers to do no harm to those who seek care, is infringed by selectively restricting access to mental healthcare in insurance coverage. Private health insurance in India by design is linked to the for-profit model which fundamentally conflicts with the principles of beneficence and non-maleficence by serving the interests of the insurance provider above those of the consumer [8, 20].

Finally, insurance processes are not transparent where insurance providers maintain information asymmetry on policy wording and rejection which negatively impacts the autonomy of the consumer, another core principle of bioethics relating to the ability to make informed decisions. Terms in the policy wording and procedures are often vague and open to interpretation which carries a risk of rejection of claims arising from mental illness. The presence of third-party administrators who influence decision making around insurance further complicates the process.

Inadequate insurance practices in relation to mental illness have been documented in contexts beyond India as well [21]. In this paper, we examine questions around insurance coverage for mental illness in the Indian context.

Research objectiveTo assess the extent of compliance with Section 21 (4) of the MHCA, we undertook a content analysis of all health insurance policies introduced or revised in the years 2020 and 2021 to understand the terms and services within coverage for mental illness. In this paper, we highlight key findings and argue for the importance of insurance coverage for mental illness on par with physical illness that may inform policy guidelines and norms for the insurance sector in India.

Methods

All insurance policies analysed for this study were sourced from the IRDAI web portal, where IRDAI publishes a compiled list of health insurance policies introduced or revised annually. Given the regulatory role of the IRDAI, this was deemed the most comprehensive method of accessing all new, relevant and updated health policies. Using this approved list for the year 2020-21 as a reference, we sourced the complete policy documents published on individual insurance providers webpages and analysed the policy wording. Policies not directly relevant to treatment of mental illness, such as travel insurance, accident policies and critical illness-specific policies (eg, cancer or Covid-19, vector-borne diseases) and/or those policies where we were unable to access the complete policy document were excluded. Government-sponsored insurance schemes at the state-level were beyond the scope of this research study.

To analyse the data, an extraction template was developed through an initial review of policy wording and identification of relevant policy features. The data extraction template was built on the principle of parity outlined in Section 21 (4) of the MHCA as well as the Master Circular on Standardisation of Health Insurance Products published in 2020 by the IRDAI, which states mental illness can no longer be listed as an exclusion criterion [9, 15]. Each policy was analysed for parity based on i) mention of mental illness in the policy wording, ii) policy features relevant to mental illness and iii) a comparison between features available for physical health conditions and mental illness. The keywords used to search for clauses relevant to mental illness within the documents, included suicide, self-harm, self-injury, psych*, mental health, mental illness, counselling, addict*, substance, alcohol*, opd, ipd, in patient, out patient and sublimit.

Results

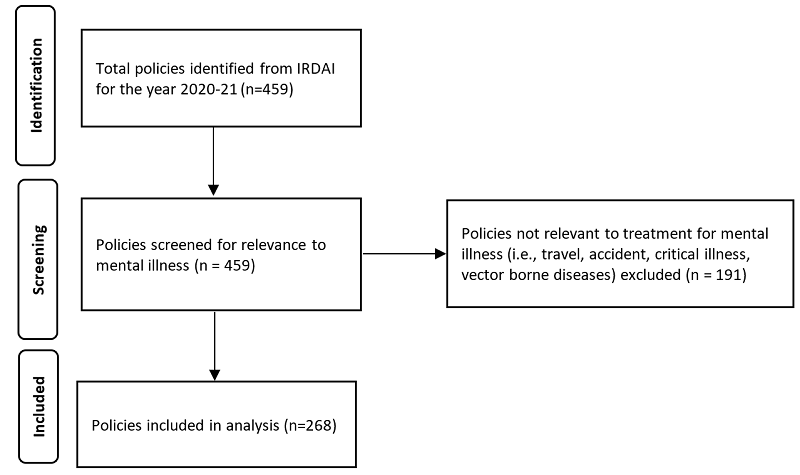

We sourced 459 health insurance policies for the year 2020-21 from the IRDAI website which were individually screened for their relevance to mental illness. Policies not directly relevant to treatment for mental illness such as travel insurance policies, accident coverage, critical illness, vector borne diseases (n=191) were excluded post screening. From this, 268 relevant policies were analysed in-depth to assess the extent of coverage for mental illness and for their compliance with Section 21 (4) of the MHCA through an analysis of policy features gathered through data extraction (see Figure 1). From the 268 relevant policies, we found most policies (n= 262) did not explicitly cite mental illness as an exclusion from their policy; however, some policies (n=6) from two insurance providers, explicitly excluded mental illness across all domains of coverage (Table 1).

Figure 1. Summary of health insurance policy documents sourced and analysed

Among the policies analysed, most included coverage for pre- and post-hospitalisation expenses and other costs associated with hospitalisation such as ambulatory care, pharmaceutical coverage and coverage for a second opinion. We found restrictions in coverage for mental illnesses such as the exclusion of attempted suicide or intentional self-injury, exclusion of addiction and substance use, restrictions via sub-limits on coverage for mental illness and restrictions on domiciliary hospitalisation and outpatient services for mental illness.

Table 1. Types of policies relevant to mental health by private insurers

Type |

Number of providers (n = 30) |

Number of policies (n = 268) |

| Policies that exclude mental illnesses in violation of section 21(4) of MHCA 2017 | 2 (7%) | 6 (2.2%) |

| Policies that have restrictions on sum insured for mental illness | 7 (23%) | 35 (13.1%) |

| Policies that explicitly exclude coverage for attempted suicide or self-injury | 29 (97%) | 224 (83.6%) |

| Policies that explicitly exclude coverage for substance use disorders and addiction | 30 (100%) | 267 (99.6%) |

| Policies that explicitly exclude coverage for domiciliary hospitalisation for mental illness | 15 (50%) | 32 (11.9%) |

| Policies that offer coverage for mental illness beyond hospitalisation (ie, outpatient services and consultations with mental health experts) | 12 (40%) | 23 (8.6%) |

Exclusion of attempted suicide or intentional self-injury

We found most policies (n=224) excluded treatment for intentional self-injury or attempted suicide from coverage, despite there being no standardised exclusion for attempted suicide or self-injury approved by the Master Circular by the IRDAI (2020) [15].

Exclusion of addiction and substance useTreatment for addiction and substance use was excluded in the wording of all policies, barring one policy (n=267). This exclusion extends to treatment for physical ailments arising from alcoholism or substance use.

Exclusion of domiciliary hospitalisationDomiciliary hospitalisation is the treatment of individuals in their home setting when hospitalisation is not feasible. We found 32 policies specified domiciliary hospitalisation for mental illness as excluded from coverage.

Restrictions via sub-limits for coverageSub-limits are monetary limits on health insurance coverage that providers place, based on type of treatment or illness. We found 32 policies (from 7 providers) applied sub-limits for claims related to mental illness. The limits ranged from 5% to 25% of total sum assured in terms of percentages and from INR 50,000 – 300,000 in terms of absolute claim amount available for mental illnesses, comparable to other specified medical procedures.

Coverage for out-patient servicesA few policies (n=32) offered coverage for treatment beyond inpatient services and hospitalisation. Of these, 16 policies explicitly offered out-patient services including consultations with experts, counselling sessions and psychological rehabilitation, included either as part of the policy or optional through an add-on package or an extra premium.

Discussion and recommendations

Our analysis of health insurance policies approved during the year 2020-21 found mental illnesses are no longer explicitly listed as exclusionary criteria for most policies. This is in accordance with Section 21 (4) of the MHCA and the Master Circular on Standardisation of Health Insurance Products published in 2020 by the IRDAI [9, 15].

As per Section 3 of the MHCA, any determination of mental illness is made in accordance with internationally or nationally accepted medical standards notified by the Central Government, such as the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD) [9]. Thus, regardless of specified mental illness, we maintain all health insurance providers should cover mental conditions recognised by the ICD. Yet, our analysis found certain practices that appeared to be discriminatory in their coverage of mental illness and it remains unclear to what extent persons with mental illnesses are supported by private insurance providers [12].

A concerning finding was that treatment for attempted suicide/self-injury and for addiction disorders are excluded by a majority of providers, in breach of the letter and spirit of the MHCA [9]. Section 115 of the MHCA states “the appropriate Government shall have a duty to provide care, treatment (including hospitalisation) and rehabilitation to a person, having severe stress and who attempted to commit suicide, to reduce the risk of recurrence of attempt to commit suicide.” In instances of intentional self-injury and attempted suicide, a person may require hospitalisation and treatment for both physical injuries and psychological distress, resulting in a need for insurance coverage. Thus, outright denial of insurance coverage for intentional self-injury and attempted suicide denies individuals the required financial support.

Similarly, despite being recognised as mental illnesses under both Section 2(s) of the MHCA, and the latest edition of the ICD-11, under Section 06 (6C40- 6C4Z), treatment for alcohol addiction and substance use disorders are excluded from insurance coverage [9]. This exclusion extends to treatment for physical ailments arising from alcoholism or substance use, thus impacting a wider population. Given the high prevalence of both addiction disorders and attempted suicide/self-injury, denial of coverage by insurance providers adds to the increasing treatment gap. In this case, unlike the exclusion of attempted suicide and intentional self-injury, this is a standard exclusion, approved by IRDAI under Code- Excl12, the exclusion of “Treatment for, Alcoholism, drug or substance abuse or any addictive condition and consequences thereof” [22].

Our analysis also found treatment-specific exclusions for physical conditions arising from psychological or psychiatric causes (eg, treatment for speech disorders were not covered under insurance policies if the speech impairments arose ‘due to psychiatric causes’). This makes a distinction on physical disorders where the cause is symptomatic of a psychological or physiological ailment. Thus, the exclusion of insurance coverage for physical conditions arising from psychiatric causes should not be ruled out by insurance providers prima facie but be decided on a case-to-case basis or by the attending physician. This holds true for domiciliary hospitalisation as well.

Regarding sub-limits, the IRDAI Master Circular (2020) makes clear “Insurers are allowed to impose sub limits or annual policy limits for specific diseases/ conditions; be it in terms of amount, percentage of sum insured or number of days of hospitalisation/ treatment in the policy. However, Insurers shall adopt an objective criterion while incorporating any of these limitations and shall be based on sound actuarial principles” [15]. However, in this case we argue restrictive sub-limits on sum insured for mental illness may have negative implications for the insured person particularly in cases where these limitations are not made clear to the consumer beforehand or limits for mental illness are small in proportion to the total sum assured, particularly given the high costs associated with repeated treatment requirements given the cyclical and episodic nature of mental illness. The matter of sub-limits for mental illness is being contested and is currently sub-judice in the Delhi High Court [23].

Finally, the recognition of out-patient services for mental illness by a few insurance providers is a welcome shift as most insurance practices focus on clinical diagnosis and treatment, often disregarding the importance of coverage for psychosocial services for mental illness [24]. Insurance providers have cited the lack of data on patterns of insurance use for persons with mental illness as a hindrance in constructing comprehensive coverage for mental illness, including out-patient services [25]. Thus, until more insurers offer coverage for such services, costs associated with out-patient services will continue to be borne by individuals.

While our analysis was restricted to the wording of policies and did not involve studying how that translates into practice, references and anecdotal evidence support our argument that patients with existing mental illness continue to be denied health insurance coverage and payment of claims. This also includes denial of coverage for treatment of health conditions typically accessible to people without a history of mental illness, going against the principle of beneficence and non-maleficence [26]. We rely on such anecdotal data in the absence of official data on rejection of new issuance and claims on insurance policies. While the IRDAI annual report publishes data on how many insurance policies have been issued during the year, there is no information on how many applications were received and how many of these were rejected. Thus, there is limited evidence on how the implementation of Section 21 (4) translates into practice [27]. In the absence of such official data, the crucial next step will be to compare health insurance policy entitlements with experiences of persons with mental illness who have sought claims for treatment of mental illness from insurance companies to effectively evaluate compliance with Section 21 (4) of the MHCA.

Ultimately, insurance providers must recognise mental illnesses need to be treated on par with physical illness and follow the ethical principles of beneficence, autonomy and non-maleficence to create optimal healthcare for all, particularly vulnerable populations groups. At present, owing to a novelty factor, some lack of clarity is expected before implementation is standardised [12, 14].

To advocate for insurers to provide more sensitive and inclusive health coverage and services for mental illness through this analysis, we recommend that:

• Insurance companies should comply with the principle of parity in letter and in spirit, to remove all differential or discriminatory terms for mental illness in compliance with Section 21 (4) of the MHCA;

• The IRDAI be more proactive in upholding its supervisory duty and identify discriminatory terms for mental illness and have them removed from insurance policies in accordance with the principle of parity for mental illness (including the removal of discriminatory sub-limits);

• The IRDAI remove addiction as an exclusion criterion in its guidelines (ie, the Master Circular, 2020) as a priority; Subsequently, insurance providers should follow suit and remove exclusion clauses for alcohol addiction and substance abuse from their policies;

• Insurance providers should remove the exclusion of treatment for intentional self-injury and attempted suicide for health insurance coverage and include coverage for this on priority;

• More insurance providers should recognise the need for coverage of mental health services beyond hospitalisation and consider adding or increasing coverage for out-patient services for mental illness such as therapy and counselling sessions, given that many experiences and manifestations of mental illness do not require hospitalisation.

• Finally, in the absence of public accessibly data, we recommend the IRDAI makes their records of number of applications for health insurance coverage made and rejected every year along with reasons for rejection publicly accessible to monitor practices around rejection including discrimination against mental illness to be transparent while enabling autonomy for consumers.

Conclusion

Our findings shed light on important gaps in health insurance coverage for mental illness, where health insurance policies continue to contain discriminatory terms for mental illness, violating the principle of parity in the MHCA under Section 21 (4). We argue for sustained advocacy efforts to bring about change in the sector and highlight the supervisory duty of IRDAI to ensure that the provisions of the MHCA are fully implemented by all insurance companies for the benefit of persons who obtain health insurance policies. Ultimately, insurance providers, both public and private, have a duty to uphold ethical principles in their practice and abide by their legal obligations to ensure quality and affordable mental healthcare for all.

Authors: Amiti Varma (corresponding author — [email protected], https:// orcid.org/0000-0002-3141-9109), Research Associate; Nikhil Jain ([email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9692-8046), Programme Manager & Research Fellow; Sayali Mahashur ([email protected]), Research Associate; Tanya Nicole Fernandes ([email protected], https:// orcid.org/0000-0002-7457-9962), Research Associate; Arjun Kapoor ([email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5620-5350), Programme Manager and Research Fellow; Soumitra Pathare ([email protected], https:// orcid.org/0000-0001-9311-9024), Director, Centre for Mental Health Law and Policy, Pune 411004, Maharashtra, INDIA.

Conflict of Interest: None to declare. Acknowledgments: None.

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

Funding: AV, SM, TF, and AK worked on this as a part of the Keshav Desiraju India Mental Health Observatory, funded by the Thakur Family Foundation.

Statement of similar work: A version of this paper has been published as an issue brief at the Keshav Desiraju India Mental Health Observatory, Centre for Mental Health Law & Policy, Indian Law Society. Available from: https:// cmhlp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Issue-Brief-Insurance-II.pdf

Data sharing: Data not made available in public domain. Please contact corresponding author for access to raw data.

To cite: Varma A, Jain N, Mahashur S, Fernandes TN, Kapoor A, Pathare S. Insurance coverage for mental illness: A review through a lens of bioethics and the MHCA, 2017. Indian J Med Ethics. 2025 Jan-Mar; 10(1) NS:10-15. DOI: 10.20529/IJME.2024.072.

Submission received: September 3, 2022 Submission accepted: March 13, 2024

Published online first: November 4, 2024

Manuscript Editor: Bevin Vinay Kumar VN

Peer Reviewers: Mukta Gundi, Madhurima Ghosh, and an anonymous reviewer

Copyright and license

©Indian Journal of Medical Ethics 2024: Open Access and Distributed under the Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits only noncommercial and non-modified sharing in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuroscience. National Mental Health Survey 2015-16 [cited 2022 Feb 01]. Available from: https://indianmhs.nimhans.ac.in/phase1/Docs/Report2.pdf

- Pathare S, Brazinova A, Levav I. Care gap: a comprehensive measure to quantify unmet needs in mental health. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27(5):463-467. https://doi.org/10.1017%2FS2045796018000100

- Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Key Indicators of Social Consumption in India: Health NSS 75th Round 2017-18 [Cited 2022 Jan 8]. Available from: https://www.mospi.gov.in/documents/213904/301563//KI_Health_75th_Final1602101178712.pdf/1edceec8-a4af-f357-b675-837e015ae20c

- Mahasur S, Varma A, Fernandes TN. Understanding costs associated with mental health care in India. Keshav Desiraju India Mental Health Observatory. 2022 Jun [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://cmhlp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Issue-Brief-Cost-of-Care.pdf

- Yadav J, Allarakha S, John D, Menon GR, Venkateswaran C, Singh R. Catastrophic Health Expenditure and Poverty Impact Due to Mental Illness in India. J Health Manag. 2023 Mar 1; 25(1):8-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/09720634231153210

- Sanghvi D. 56% Indians still don’t have a health cover. Mint. 2018 Dec 4 [Cited 2022 Feb 18]. Available from: https://www.livemint.com/Money/YopMGGZH7w65WTTxgPLoSK/56-Indians-still-dont-have-a-health-cover.html

- Sharma YS. Nearly 30% of Indian population don’t have any health insurance: Survey. The Economic Times. 2021 Oct 29 [Cited 2022, Feb 18] Available from: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/banking/finance/insure/nearly-30-of-indian-population-dont-have-any-health-insurance/articleshow/87367884.cms.

- Duggal R. Private health insurance and access to healthcare. Indian J Med Ethics. 2011 Jan-Mar;8(1).:28-30. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2011.010

- Government of India. The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017. 2017 Apr 7 [Cited 2022 May 23 ] Available from: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2249/1/A2017-10.pdf.

- United Nations. Article 25 – Health. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. [Cited 2022 Jan 22] Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/article-25-%20health.html

- Varma A, Mahashur S, The Mental Healthcare Act 2017 & health insurance coverage: A narrative experience of accessing private health insurance for mental health conditions. Keshav Desiraju India Mental Health Observatory. 2021 Dec [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://cmhlp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Lived-Experience-Profile_Insurance.pdf

- Singhai K, Sivakumar T, Angothu H, Jayarajan D. Review of Individual Health Insurance Policies for Mental Health Conditions. Indian J Priv Psychiatry. 2021;15(1):3-9. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10067-0076

- Kapoor A, Mahashur S. Right to Health Insurance: Ensuring Parity for Mental Illness in India. The Jurist.2021 Jun. [cited 2022 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.jurist.org/commentary/2021/06/kapoor-mahashur-health-insurance-india/

- Ghosh M. Mental health insurance scenario in India: Where does India stand? Indian J Psychiatry. 2021;63(6):603-605. https://doi.org/10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_148_21

- Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority. Master Circular on Standardisation of health insurance products 2020 Jun [cited 2022 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.irdai.gov.in/ADMINCMS/cms/frmGuidelines_Layout.aspx?page=PageNo4196&flag=1

- High Court of Delhi. Shikha Nischal Vs. National Insurance Company Ltd & ANR. Legitquest. 2021 April 19. [cited 2022 Jan 22]. Available from: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/16678186/

- Jain Q. Bombay High Court stays Insurer’s Rejection of Bipolar Person Policy Proposal. Law Insider India. 2021 Mar 7. [cited 2022 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.lawinsider.in/news/bombay-high-court-stays-insurers-rejection-of-bipolar-person-policy-proposal

- Gillon R. Medical ethics: four principles plus attention to scope. BMJ. 1994;309(6948):184-188. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.309.6948.184

- DE Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Cohen D, Asai I, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52-77. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014.x

- Gopichandran V. Ayushman Bharat National Health Protection Scheme: an Ethical Analysis. Asian Bioeth Rev. 2019 Apr 3;11(1):69-80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41649-019-00083-5

- Mental Health Council of Australia, Beyondblue (Organisation). Mental Health Discrimination & Insurance: A Survey of Consumer Experiences 2011. 2011[cited 2022 Jan 22]. Available from: https://mhaustralia.org/sites/default/files/imported/component/rsfiles/publications/Mental_ Health_Discrimination_and_Insurance_A_Survey_of_Consumer_Experiences_2011.pdf

- Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority. Guidelines on Standardisation of Exclusions in Health Insurance Contracts. 2019 Sep 27 [cited 2022 Feb 01]. Available from:https://www.irdai.gov.in/ADMINCMS/cms/whatsNew_Layout.aspx?page=PageNo3916&flag=1

- Bhatikar G, Doshi M. Insurance – “Mental Illness” Be Included Without Discrimination – Delhi High Court. Mondaq. 2021 May.[cited 2022 Feb 01]. Available from: https://www.mondaq.com/india/insurance-laws-and-products/1067196/insurance-mental-illness-be-included-without-discrimination-delhi-high-court

- World Health Organization, United Nations. Mental health, human rights and legislation: Guidance and practice. 2023. [cited 2022 Feb 01]. Available from: https://waps.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/WHO-OHCHR-Mental-health-human-rights-and-legislation_web.pdf

- Sharma A. Should you count on health insurance for mental illness treatment? Not blindly. Business Today. 2020 Oct 15 [cited 2022 Feb 01]. Available from: https://www.businesstoday.in/personal-finance/insurance/story/should-you-count-on-health-insurance-for-mental-illness-treatment-not-blindly-275850-2020-10-15

- Bhuyan A. COVID-19: Insurers Are Denying Policies To Disabled Despite Govt Strictures. 2020 Nov 25 [cited 2022 Feb 01]. Available from: https://www.indiaspend.com/covid-19-insurers-are-denying-policies-to-disabled-despite-govt-strictures/

- Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority. IRDAI Annual Report 2019-20. Published online 2020. [cited 2022 Feb 01]. Available from: https://irdai.gov.in/document-detail?documentId=696019Th