RESEARCH ARTICLE

How trainee doctors and nurses react to simulated scenarios of violence against healthcare workers: A cross-sectional study

Japleen Kaur, Shruti Sharma, Manik Inder Singh, Sarit Sharma

Published online first on February 3, 2022. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2022.009Abstract

Medical and nursing students may have to face healthcare-related violence, especially now as they may be doing clinical duty during the Covid-19 pandemic. This study was conducted to analyse the perceptions and attitudes of medical and nursing students towards violence against healthcare workers (HCWs), when presented with audio-visual depiction of simulated scenarios. This cross-sectional study was conducted over a period of six months (April to September 2019) among the undergraduate medical and nursing students of first, second, pre-final and final years making it a total of 800 students. Video clips were shown to the students pertaining to HCWs’ interactions with patients and relatives, and their responses were noted. Among 615 participants who completed the proforma, 248 (40%) students reported having observed or experienced violence in their clinical postings. Overall, 70.7% of medical and 68.5% of nursing students said that they would report incidents of violence to the authority. The questionnaire based on video-based simulated scenarios brought forth the perception that in triggering an act of violence, both the healthcare worker and the attendant could be at fault and full disclosure of complications was a necessary step in preventing such an act of violence. Sensitisation about the same should be incorporated into the teaching curriculum by using simulated scenarios to prepare them to manage such incidents.

Keywords: Ethics, healthcare workers (HCWs), medical students, nursing students, violenceIntroduction

The incidence of violence against healthcare workers (HCWs) in hospital settings is showing an increasing trend. According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) of the United States, approximately 75% of nearly 25,000 workplace assaults reported annually in the US, occurred in healthcare and social service settings (1). Patients’/relatives’ aggression has become a major occupational hazard for people working in the healthcare sector and acts as a major contributor to the rising stress levels and burnout in HCWs (2, 3). According to the Indian Medical Association, over 75% of doctors have faced violence at some point of time in India. The actual rate may be even higher as there is underreporting of violent incidents (4). It was also found that there were very few cases that had reached the courts and no person was accused of assault or penalised (5, 6). Medical and nursing students are exposed to such instances when they visit hospitals during their clinical postings. This can be demotivating for these students and might even induce anxiety or make them feel threatened (7). Most of the studies that have been conducted across the world include quantitative analysis of such incidents but little has been done to analyse the perceptions of healthcare workers and students towards such violence.

The present study was conducted to analyse the perceptions and attitudes of medical and nursing students towards violence against HCWs, when presented with audio-visual depiction of simulated scenarios.

Materials and methods

Study designThis cross-sectional study was conducted from April to September 2019 in a tertiary care teaching institution, in a medical and nursing college setting, after obtaining approval from the institutional ethics committee. A written informed consent was obtained from all the participants and they were assured about the confidentiality and anonymity of data. Undergraduate students of the first, second, pre-final and final years of a medical and nursing college, having an annual admission of 100 students each, were included in the study. So, considering all the batches, 800 students were eligible for the study.

DefinitionWorkplace violence (WPV): Incidents where staff is abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances related to their work, including commuting to and from work, involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well-being or health are included in workplace violence (8). Violence includes physical assault, homicide, verbal abuse, bullying/mobbing, sexual and racial harassment and psychological stress.

Description of toolsVideo clips

Video clips 1 and 2, one depicting an outpatient and the other an inpatient setting, were shown to medical students. Video clip 3 pertaining to HCWs’ interaction with patients and relatives was shown to the nursing students. Responses of medical and nursing students were noted on a pre-designed questionnaire. The scripts of the video clips were written by the investigators and shown to subject experts, and validated after incorporating necessary changes. The videos were then shot in the vernacular language (with subtitles included), with professional actors (technical team) to whom the purpose of the study was explained in detail. The scripts of the video clips are attached as Annexure 1(available online only).

Self-administered questionnaire

A questionnaire was constructed, based on previous research on the subject of WPV and was validated by subject experts after viewing the video clips. Specific questions related to the video clips were also incorporated into the questionnaire and an open-ended question regarding suggestions by participants to reduce WPV was added at the end. A pilot study was conducted among ten medical and nursing students each to assess the video clips and questionnaire for language and comprehension. Their suggestions were then incorporated into the proforma [Annexure 2, available online only].

Data collectionOn a fixed date, a short interaction for each pre-selected batch of medical and nursing students was conducted by the investigators with the help of the relevant subject teachers. Written informed consent was taken from the participants and the videos were displayed. Following this, the questionnaire was distributed. This was repeated for all the batches of nursing and medical students.

Data analysisThe data were entered into Microsoft Excel and then tabulated to draw meaningful conclusions. Data were recorded and analysis was done using ratios and proportions. The qualitative data were analysed by generating themes from the open-ended responses given by the participants.

Results

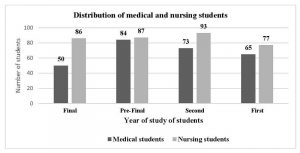

Of the 800 eligible students, MBBS (medical) and nursing batches had 400 students each, of which 272 medical and 343 nursing students filled the proforma and were included in the study, making a response rate of approximately 77% (n = 615). Figure 1 shows the year-wise distribution of medical and nursing participants in the study.

Figure 1: Distribution of medical and nursing students with respect to year of study (N = 615)

The average age of our study participants ranged from 17-23 years, representing a relatively younger age group.

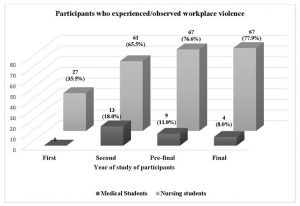

Among the medical students, 4 (8%) of the final year, 9 (11%) of the pre-final year, 13 (18%) of the second year, and none of the first-year batch reported having observed or experienced violence in their clinical postings. It was also observed that a greater number of nursing students as compared to medical students experienced or observed incidents of violence against HCWs in clinical settings [Figure 2].

Figure 2: Distribution of participants who experienced/observed workplace violence

Most of the medical students of the second (64, 87.5%), pre-final (80, 94.4%) and final year (45, 89.8%) claimed that they would report incidents of WPV, whereas only 7 (11%) medical students from the first year stated that they would report such incidents. Among the nursing students, 60 (78.9%) from the first year, 56 (60.2%) from the second year, 63 (72%) from the pre-final year and 48 (62.7%) from the final year said that they would report such an incident.

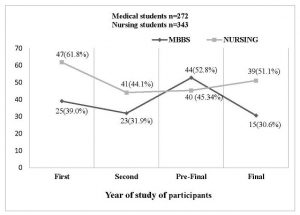

Among the medical students of all batches, 30.6% to 52.8% reportedly knew about a law to curb violence against the medical profession [Figure 3], whereas awareness among the nursing students of legal provisions regarding WPV was slightly higher (44.1%-61.8%). Only 51 (18.7%) of the medical students and 127 (37%) of the nursing students perceived the legal provisions to be efficacious.

Figure 3: Response of participants regarding awareness about law against workplace violence

Responses shown by medical students to the videos

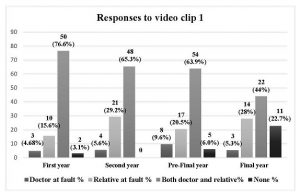

In response to the question pertaining to video clip 1, 174 (64%) medical students from different years stated that both the doctor as well as the relative were at fault, whereas 62 (22.7%) medical students felt it was the fault of the relative which led to the violence in the given scenario [Figure 4]. The students were divided in their opinions about what they would do in a similar situation. Approximately 77% (50) of the first year, 65% (47) of the second year, 63% (53) of the pre-final and 44% (22) of the final year medical students expressed the view that they would refer the patient to a colleague.

Figure 4: Responses of the medical students to video clip 1 with respect to the

person responsible for aggression by relatives (N = 272)

Among the medical students, only 11 (22%) from the final year, 5 (6%) from the pre-final and 2 (3%) from the first year suggested that they would have calmly asked the relative to wait outside while continuing to examine the patient and would not have entered into an argument with the relative at all.

Pertaining to video clip 2, more than half of the medical students from all batches (166, 61%) considered that the doctor was wrong in not explaining all the possible complications to the patient [Table 1].

Table 1: Responses of medical students on whether the doctor was right in

not explaining all the possible complications to the patient (video clip 2)

Year |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

Not sure (%) |

First |

11(17) |

40(61.5) |

14(21.5) |

Second |

18(24.7) |

49(67.1) |

6(8.2) |

Pre-final |

22(26.2) |

46(54.8) |

16(19) |

Final |

3(6) |

31(62) |

16(32) |

Total |

54 (19.8) |

166 (61) |

52 (19.1) |

Reasons perceived by approximately 50% (134) of the medical students for not explaining the possible complications to the patient in the second clip, included the doctor not wanting to frighten the patient unnecessarily. Around 169 (62%) of the students believed that the incident could have been avoided had the doctor explained all the possible complications to the patient. Most of the medical students (186, 68.4%) from all batches felt counselling and empathy were the correct responses to a patient’s/relative’s aggression. Some respondents differed and said that they considered responding with aggression (31, 11.3%); ignoring the patient’s action (8, 2.9%) and calling the security staff (48, 17.6%) as the right response to the patient’s action.

The responses of nursing students were also noted after showing them video clip 3 of patient/relative-nurse interaction. Most students from the final year (65, 76%) considered the patient’s relative to be at fault, while first year and pre-final students were equivocal about the relative alone, as well as both nurse and relative being at fault. Most students from the second year (62, 67%) considered no-one to be at fault [Table 2].

Table 2: Responses of nursing students as to who was at fault in the scenario

based on video clip 3 (n = 343)

Year |

Nurse (%) |

Relative (%) |

Both (%) |

None (%) |

First |

0 |

37(48) |

36(47) |

4(5.2) |

Second |

2(2.1) |

17(18.3) |

12(12.9) |

62(66.7) |

Pre-Final |

0 |

40(46) |

43(49.4) |

4(4.6) |

Final |

2(2.3) |

65(75.6) |

17(19.8) |

2(2.3) |

Approximately 43% (40) of students from the second and 50% (43) from the final year were of the opinion that they would have done what was shown in the clip, while a majority of the first year (33, 43%) and the pre-final year (50, 57%) students stated that they would have made the patient sign a consent form stating that they were going against hospital policy of their own will. A small percentage of nursing students (33, 9.6%) from all batches also suggested that they would have called in a senior doctor. A majority of students from both the nursing (76-83%) and medical (69-83%) batches were of the view that the introduction of attitude, ethics, and communication (AETCOM) training in the course curriculum would be beneficial in empowering young doctors and nurses to better deal with such instances.

Factors responsible for violence against HCWsThe medical and nursing students were asked to rank each perceived cause of WPV against HCWs, and the average of the ranks given by the students of a particular batch was taken and tabulated [Table 3].

Table 3: Factors responsible for violence against healthcare workers as perceived

by medical students

Factors |

Average rank (Scale 1-7) |

|||

Final |

Pre-final |

Second |

First |

|

| Rising distrust among patients towards doctors | 3.26 |

3.85 |

3.01 |

2.30 |

| Increased patient load: increased patient to doctor ratio | 3.50 |

4.05 |

3.72 |

3.24 |

| Easy accessibility of medical information on the internet | 4.40 |

4.03 |

4.50 |

3.61 |

| Uneducated patients | 2.68 |

4.18 |

3.85 |

2.70 |

| Impact of media on patients’ perceptions about healthcare workers | 4.60 |

4.62 |

3.83 |

3.26 |

| Rising cost of healthcare | 4.45 |

4.07 |

4.19 |

2.81 |

| Patient’s characteristics such as intoxication, acute psychosis, delirium and drug seeking behaviour | 4.97 |

3.39 |

4.82 |

3.40 |

Patient’s condition at the time of admission such as intoxication, acute psychosis, delirium and drug seeking behaviour, or external factors such as easy accessibility of medical information on the internet, impact of media on patients’ perception, rising cost of healthcare, increased patient to doctor ratio, were ranked higher by medical students as the most probable cause of violence towards HCWs [Table 3].

Patient’s frustration pertaining to hospital policy, increased patient load, increased patient to nurse ratio, decreased quality of healthcare, long waiting hours and impact of media were reported as the most probable causes of violence against HCWs by nursing students [Table 4].

Table 4: Factors responsible for violence against healthcare workers as perceived by nursing students

Factors |

Average rank (Scale 1-10) |

|||

Final |

Pre-final |

Second |

First |

|

| Patient frustration pertaining to hospital policy | 6.40 |

6.60 |

5.36 |

6.03 |

| Understaffed hospitals | 5.61 |

5.15 | 5.02 |

5.60 |

| Increased patient load; Increased patient to nurse ratio | 5.86 |

7.08 |

5.61 |

5.18 |

| Rising cost of healthcare | 5.20 |

5.65 |

5.76 |

5.81 |

| Biased mindset of patients | 5.47 |

5.30 |

6.15 |

4.98 |

| Patient’s characteristics such as intoxication, acute psychosis, delirium and drug seeking behaviour | 5.64 |

4.52 |

5.37 |

6.32 |

| Long waiting hours for the patient | 5.58 |

6.38 |

5.21 |

4.93 |

| Decreased quality of healthcare | 4.59 |

4.69 |

5.26 |

5.90 |

| Uneducated patients | 5.52 |

5.17 |

5.38 |

5.05 |

| Impact of media on patients’ perception about healthcare workers | 5.10 |

4.45 |

5.46 |

5.06 |

Suggestions

Qualitative analysis was done to generate themes based on the suggestions given by the students regarding prevention of WPV. Most of the medical and nursing students considered introduction of ethics in the curriculum, explaining hospital policies to patients, increased security, reduction of healthcare costs, increased communication, guidance of senior doctors and proper informed consent explaining all the complications, as some of the measures to prevent violence against HCWs [Table 5].

Table 5: Themes generated based on suggestions by students to prevent healthcare-related violence

Medical students (N = 272) |

Nursing students (N = 343) |

||

Themes |

n (%) |

Themes |

n (%) |

| Increased security | 239 (88) |

Explain hospital policy to the patients | 320 (93) |

| Introduction of ethics in curriculum | 209 (77) |

Increased security | 296 (86) |

| Stricter government laws and policies | 196 (72) |

Interpersonal relationship | 293 (85) |

| Public awareness programmes via the media and social media | 187 (69) |

Increased empathy | 288 (84) |

| Informed consent including all complications | 176 (65) |

Introduction of ethics in curriculum | 238 (69) |

| Increased communication | 175 (64) |

Stricter government laws and policies | 212 (62) |

| Guidance to junior doctors by the senior doctors | 157 (58) |

Public awareness programmes via the media and social media | 212 (62) |

| Reduction of healthcare cost | 133 (49) |

Better nurse to patient ratio | 181 (53) |

| Soft skills training programmes for doctors | 62 (23) |

||

| Limited working hours | 46 (17) |

||

| Appointment based OPDs | 106 (39) |

||

| Self-defence classes | 21 (8) |

||

Some verbatim suggestions from the medical students to prevent such instances of violence were:

- 1. There should be increase [in] the seats in medical colleges to compensate doctor: patient ratio.

- 2. It is the duty of the doctor to explain all the complications and every aspect of the case.

- 3. More than one hospital staff should be present with the doctor in the patient’s room at a time and security should be tight.

- 4. Senior doctors should assist junior doctors in early stages and guide them.

- 5. Do not reply aggressively even if the attendant is rude. It can worsen the situation.

Some verbatim suggestions given by the nursing students were:

- 1. Counsel the patient and attendant regarding any problem faced by them during their hospital stay.

- 2. Show empathy to the patient and relative and talk politely.

- 3. Increase nurse to patient ratio (due to less number of staff nurses this problem is observed in hospitals)

- 4. If patient becomes violent, call the security and take appropriate strict action against the patient or his relative.

Discussion

Workplace violence against HCWs is a global issue, and according to WHO, between 8% and 38% of healthcare workers suffer physical violence at some point in their careers. Many more are threatened or subjected to verbal aggression (9). Out of violence faced by healthcare professionals, the most important is patient and visitor violence (PVV) (10). The present study focusses on the perceptions of medical and nursing students regarding PVV.

The age of our study participants ranged from 17-23 years, representing a relatively younger age group as compared to other studies which had interns, post-graduate students and doctors/nurses as the target population (11, 12).

In our study, a smaller percentage of medical students (9.5%) reported having experienced or observed violence against HCWs in hospital settings, in contrast to other studies which were conducted mainly amongst interns, post-graduate residents and senior residents (10, 11, 12). In a study conducted among second- and third-year resident doctors from three colleges in Uttar Pradesh, it was observed that 69.5% of doctors reported experiencing violence in one or other form in the previous one year (11, 12). Another study conducted at a teaching hospital in Punjab reported that 97% of participants reported being aware of rising incidents of violence against doctors (12). The low exposure to violence reported by our medical students may be because of less clinical exposure among undergraduate medical students as compared to post-graduate students or senior residents. The present study however, showed a larger number of nursing students (35-78%) reported having experienced first-hand or observed violent acts in their clinical postings. This was consistent with a similar finding in a research study conducted among practising nurses in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, wherein three-fourths of the participants reported having experienced such acts of violence (13). A possible reason for the disparity among the nursing and medical students could be greater clinical exposure of nursing students during the training period compared to medical students.

Many medical and nursing students in our study were not aware of legal provisions in the Indian legal system regarding punishment or penalty for offenders involved in workplace violence. There is also lack of faith in the judicial system among students, which is alarming and raises a need to make laws and policies more stringent. We need a robust judicial system that will support the medical fraternity as well as the general public, wherever it is needed. There have been attempts by many state governments to make laws to protect medical professionals against PVV, but very few cases have reached the courts or seen the culprits penalised (14).

There could be many factors leading to such acts of violence including the poor health condition of the patient leading to relatives being under stress and financial pressure due to high healthcare costs. The nurses, students, and residents become a soft target for relatives to vent the anger they feel against the system. Easy accessibility to medical information on the internet, uneducated patients, increased patient to doctor/nurse ratio, impact of the media on patients’ perception about HCWs, etc, were perceived to be some of the leading causes of violence by the students in the present study. In another similar study, the factors considered responsible for WPV were unexpected death, unexpected complication, patient unlikely to improve, extended hospital stay, staff shortage, poor hospital administration, etc (15).

Their responses to the video reflected that though many medical students perceived that in triggering that act of violence, both the doctor and the relative could be at fault, there were some students who considered either the relative or the doctor to be at fault, and said they would have referred the patient to another doctor if they had been busy. The responses of medical students to the second video were also varied and most students felt that an explanation of all possible complications is imperative while taking informed consent. On being shown the video, the nursing students’ responses regarding who was at fault were divided, some feeling it was the nurse and others the relative, or the relative alone, or that no one was at fault. Many students considered that a better response to a patient’s aggressive behaviour is counselling and empathy rather than resorting to counter arguments and violent measures. This study had two-dimensional implications. The video that was shown to the students acted both as a means of sensitisation and of assessing how the students would act in a similar situation.

As more nursing and medical students are now having clinical postings especially during the Covid-19 pandemic, they are more exposed to such scenarios at the workplace. The students suggested that sensitisation programmes for the general public via the news and social media, stricter laws and policies, attitude training programmes and soft skills training for HCWs, providing quality healthcare at a reduced cost and increasing security in hospitals, would be effective measures in controlling incidents of violence in healthcare settings. It was also suggested by students that training in handling WPV and in ethics be made a part of the regular teaching curriculum of medical and nursing students. The nursing students suggested that the patients must be made aware of hospital policies to lower the rate of occurrence of such incidents. The foundation course, early clinical exposure, and AETCOM module introduced by the Medical Council of India (now, National Medical Commission) in the MBBS course is a step in the right direction in preparing budding medical students to face such scenarios.

The main limitation of our study is that though the participants were advised to answer with all honesty, some students may have had earlier knowledge of the questions and this may have influenced their responses, as data collection from all batches could not be done at the same time.

In conclusion, the present study showed that medical and nursing students had less experience of violence against HCWs and were unsure about the efficacy of existing laws against perpetrators of violence. So, teaching them about various issues related to healthcare-related WPV, and sensitisation on the importance of ethics and communication in patient care should be an integral part of the undergraduate curriculum.

Funding source: We would like to thank the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) for giving us the opportunity to conduct this research and for fully funding this research under the short-term studentship (STS) project (2019-20589) which was granted to the first author Japleen Kaur.

Acknowledgements:• We would like to thank the Faculty of the Department of Community Medicine, Dayanand Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana for validating the video clips and questionnaire.

• We would also like to extend our gratitude to our technical team, Mr. Arshdeep Singh Lubana and Mr. Bir Devinder Singh, for the technical support provided in shooting the videos.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- The Joint Commission. Physical and verbal violence against health care workers. Sentinel Event Alert. 2018 Apr 17 [cited 2019 Jun 23];59:1-9. Available from: https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sea-59-workplace-violence-final2.pdf

- Amte R, Munta K, Gopal PB. Stress levels of critical care doctors in India: A national survey. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2015 May;19(5):257–64.

- Grover S, Sahoo S, Bhalla A, Avasthi A. Psychological problems and burnout among medical professionals of a tertiary care hospital of North India: A cross-sectional study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018 Apr-Jun;60(2):175–88.

- Dey S. Over 75% of doctors have faced violence at work, study finds. The Times of India. 2015 May[cited 2021 Dec 18]. Available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/over-75-of-doctors-have-faced-violence-at-work-study-finds/articleshow/47143806.cms

- Nagpal N. Incidents of violence against doctors in India: Can these be prevented? Natl Med J India. 2017 Mar-Apr;30(2):97-100.

- Choudhary H. Lalita Kumari v. Government of Uttar Pradesh: touching upon untouched issues. (AIR 2012 SC 1515, November 2012) Nirma University Law Journal. 2013 July; 3(1): 99-108.

- di Martino V. Workplace violence in the health sector. Relationship between work stress and workplace violence in the health sector. 2003[cited 2020 Nov 18] Available from: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/interpersonal/WVstresspaper.pdf

- World Health Organization. Workplace violence in the health sector – WHO – Country case studies research instruments, Survey Questionnaire. 2003[cited 2019 Apr 18] Available from: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/interpersonal/en/WVquestionnaire.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organization. Preventing Violence against Health Workers. 2003 Jul 3[cited 2019 Oct 08] Available from: https://www.who.int/activities/preventing-violence-against-health-workers

- Kumar M, Verma M, Das T, Pardeshi G, Kishore J, Padmanandan A. A Study of workplace Violence Experienced by Doctors and Associated Risk Factors in a Tertiary Care Hospital of South Delhi, India. J Clin Diag Res. 2016 Nov;10:LC06– 10.

- Singh G, Singh A, Chaturvedi S, Khan S. Workplace violence against resident doctors: A multicentric study from government medical colleges of Uttar Pradesh. Indian J Public Health. 2019 Apr-Jun;63:143-6.

- Sood R, Singh G, Arora PK. To study medical students’ perspective on rising violence against doctors. Do they consider obstetrics and gynecology a risky branch? Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug; 6(8):3314.

- Mishra S, Chopra D, Jauhari N, Ahmad A, Kidwai NA. Violence against health care workers: a provider’s (staff nurse) perspective. Int J Community Med Public Heal. 2018 Sep;5(9):4140.

- Reddy IR, Ukrani J, Indla V, Ukrani V. Violence against doctors: A viral epidemic? Indian J Psychiatry. 2019 Apr; 61(Suppl 4):S782-S785.

- Sharma S, Gautam PL, Sharma S, Kaur A, Bhatia N. Questionnaire based Evaluation of Factors Leading to Patient-physician Distrust and Violence against Healthcare Workers. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2019 Jul; 23(7):302–9.