RESEARCH ARTICLE

Ethical and humanitarian considerations in allocating healthcare resources during infectious disease emergencies: A scoping review

Mohammad Reza Fallah Ghanbari, Mehdi Safari, Katayoun Jahangiri, Zohreh Ghomian, Mohammad Ali Nekooie

2026. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2026.003Abstract

Background: Infectious diseases can lead to emergencies, posing ethical and humanitarian challenges in allocating basic minimum and specialised healthcare resources. This study aims to investigate the ethical and humanitarian considerations in allocating healthcare resources during infectious disease-related healthcare emergencies.

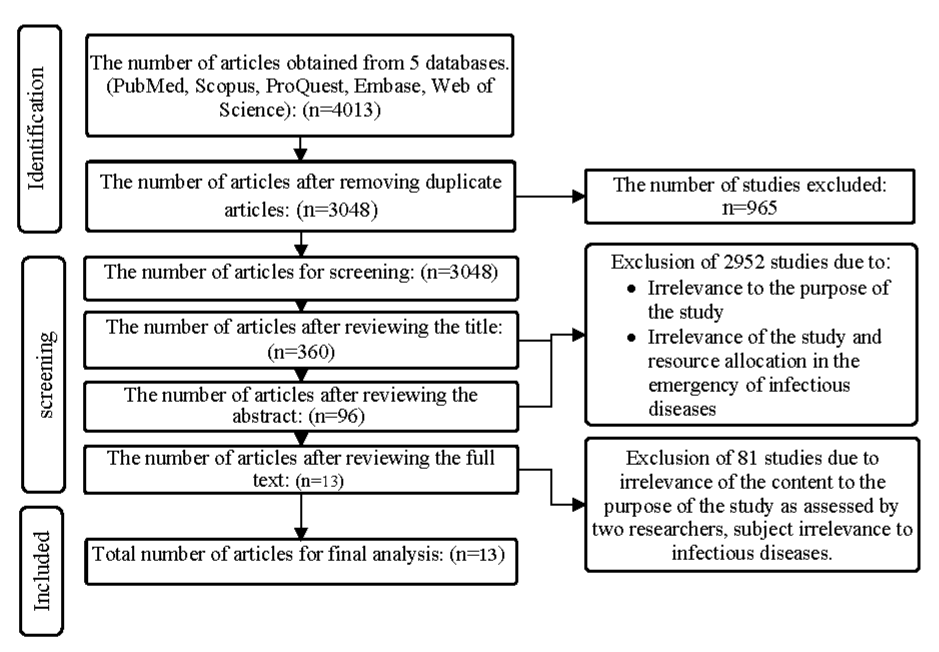

Methods: This research employed a scoping review approach following Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. Keywords related to the research topic were searched for in medical subject headings, including PubMed, Scopus, ProQuest, Embase, and Web of Science, covering the period from 1992 to 2023.

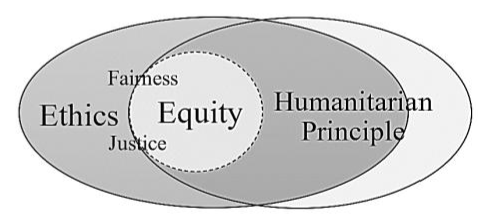

Results: Out of 4,013 articles, 13 relevant articles were extracted for final review. Findings reveal a limited application of humanitarian principles, with ethical principles like equity and justice dominating hospital-level decisions. Equity was defined under the ethics theme, and achieving equity can be considered the central theme of the framework of humanitarian principles. Humanitarian principles guide aid in crises; but ethical principles shape broader human conduct. Also, there is a significant relationship between ethics and humanitarian principles.

Conclusion: This study emphasises the need to integrate humanitarian and ethical principles into resource allocation to ensure their effective implementation in healthcfare delivery, particularly during infectious disease outbreaks, to prevent discrimination and injustice. Additionally, establishing practical criteria aligned with humanitarian principles is essential for equitable resource distribution in pandemics.

Keywords: humanitarian principles, ethical principles, resource allocation, infectious disease, epidemics, healthcare.

Introduction

Infectious diseases pose a significant threat to human society, primarily manifested in resource-scarce regions [1]. Pandemics can challenge the healthcare system while allocating scarce resources, which is further exacerbated in the contexts of poverty, malnutrition, insecurity, and weak infrastructures [2]. Infectious diseases can potentially give rise to humanitarian emergencies. This condition would affect the lives and well-being of a substantial section of the community, necessitating the involvement of various institutions in response [3]. In recent years, the Covid-19 pandemic presented numerous challenges to the healthcare system, with resource allocation being among its major issues worldwide. During this pandemic, the demand for essential medical equipment escalated significantly so that the available resources could not meet these needs. For instance, the need for hospital beds and prioritisation for patient placement became intricate challenges [4]. Some items needed during the Covid-19 pandemic were specialised equipment, which, even in normal conditions, involve unique provision and access challenges [5].

The experiences of the 2020 Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo also demonstrated the need to establish and evaluate ethical and human considerations in resource allocation [1]. In these conditions, the lack of ethical frameworks for fair distribution and the gap between expectations and resources can lead to dissatisfaction among recipients [2]. In this regard, equity and utility have been proposed as guiding principles for resource allocation during pandemics. However, balancing equity and utility in resource allocation during pandemics remains challenging, fuelling debates over ethical versus societal priorities. Key issues include prioritising equitable access while maximising societal benefit [6].

Humanitarian principles — humanity, impartiality, neutrality, and independence — should guide crisis response, including in infectious disease emergencies, ensuring dignified, non-discriminatory assistance independent of political or socio-economic biases, as adopted by the United Nations and 450 international organisations [3]. During pandemics, the right to health demands safe, timely, quality care, with resource management prioritising this right [7]. However, optimal disaster management hinges on time-constrained decisions with limited information, often leading to moral dilemmas for healthcare professionals prioritising patients amid resource scarcity [8, 9]. Inappropriate resource allocation can cause societal dissatisfaction and erode trust in the system [10].

Resource management during infectious disease outbreaks involves complex, multi-level challenges that extend beyond routine operational constraints. Critical issues include case detection, quarantine implementation, diagnostic testing, vaccination rollout, treatment provision, and ensuring equitable access to care and medications at both individual and societal levels. These multifaceted demands render resource allocation decisions particularly challenging [1]. Given the issues raised, this scoping review was undertaken to explore how humanitarian and ethical principles are applied in resource allocation during infectious disease outbreaks, and to identify the barriers and facilitators influencing their effective implementation.

Method

Following the Arksey and O’Malley framework [11], this study used a scoping review to examine how resource allocation based on humanitarian and ethical principles was applied in infectious disease emergencies.

The search inquiry guiding the study was: “How are humanitarian and ethical principles applied in resource allocation for infectious disease-related emergencies?”

Protocol registration and reportingThis study was approved by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran under the code of IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1401.155. The study protocol is also registered under the Research Registry database (reviewregistry1820) and is being reported in accordance with the recommendations specified in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis: extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [Supplementary File 1]. The planned review will be reported using the PRISMA-ScR 2018 statement and any amendments to the protocol will be documented in the final review [12].

Databases and search strategyIn this study, all articles published in five databases, PubMed, Scopus, ProQuest, Embase, and Web of Science, in the time period 1992 to 2023 were selected. Keywords related to the research title were searched using controlled vocabulary terms in the Medical Subject Headings in the databases, and a consistent strategy was applied across all databases after reviewing the results in PubMed. The search strategy for all scientific databases is provided in Supplementary File 2. The search strategy in PubMed was as follows:

((”emergency*”[Tiab] OR “Disaster”[Tiab] OR “Pandemic”[Tiab] OR “Epidemic”[Tiab]) AND (”Communicable Disease”[Tiab] OR “Infectious Disease”[Tiab] OR “contagious disease”[Tiab]) AND (”Humanitarian Principle”[Tiab] OR “conduct code*”[Tiab] OR “humanity”[Tiab] OR “neutrality”[Tiab] OR “impartiality”[Tiab] OR “independence”[Tiab] OR “Ethics”[Tiab] OR “resource*”[Tiab] OR “Resource management”[Tiab] OR “Resource Allocation”[Tiab] OR “Humanitarian action”[Tiab] OR “Humanitarian logistics”[Tiab] OR “Humanitarian aid”[Tiab] OR “Humanitarian supply Chain”[Tiab] OR “Humanitarian supply Chain management”[Tiab] OR “Emergency Medicine”[Tiab] OR “Relief”[Tiab]))

In this study, all articles and scholarly texts relevant to the research question were considered for analysis.

Inclusion criteria: Since humanitarian principles are more recent than ethical principles and were introduced in 1991, texts published in the time frame of 1991 to 2023 in the databases were sought [13]. Additionally, this study includes texts focused on resource allocation in infectious disease-related emergencies, specifically those aligned with humanitarian and ethical principles, where the search keywords appear in the title or abstract. It encompasses various publication formats, such as original research, review articles, case studies, and letters to the editor. Additionally, studies discussing the barriers and facilitators to applying humanitarian and ethical principles were included.

Exclusion criteria: Articles were excluded if they were published in languages other than English or if their full text was not accessible.

Selection and charting dataArticles were imported into EndNote X7 for efficient management. Two researchers (MF, MS) initially assessed titles and abstracts against inclusion/exclusion criteria, reviewing full texts when needed for final selection. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, with a third researcher (KJ) consulted if necessary. Articles were excluded if irrelevant, lacking resource allocation content, or with inaccessible full texts [14]. The quality of included articles was evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) instruments. Data were methodically collected, synthesised, and documented, including details such as title, year, country, author, study type, methods, and key findings. The PRISMA checklist related to the article is provided in Supplementary File 1. A deductive thematic synthesis categorised findings under humanitarian principles (humanity, neutrality, impartiality, independence) and ethical issues, while an inductive approach identified barriers and facilitators from contextual study data [12, 15].

Results

A total of 4013 articles were retrieved across five databases using search terms, with 3048 remaining after deduplication. Title screening reduced these to 360, abstract review to 96, and full-text assessment reduced the list to 13 articles in the final list. Figure 1 depicts the articles selection process, and Table 1 shows data charting. Findings are organised by ethical and humanitarian principles below.

Table 1. Characteristics of the final selected articles

|

Title |

Year |

Country, (author) |

Type of study, Methods |

Key findings |

|

Allocation of intensive care resources during an infectious disease outbreak: a rapid review to inform practice |

2020 |

Canada, (Kirsten M) |

Rapid review, Data charting |

Criteria for triage when ICU resources are scarce: Substantive values (distributive justice or fairness, duty to plan, duty to provide care, equality, equity, reciprocity, stewardship, trust) Procedural values (reasonable, open and transparent, inclusive, responsive, accountable), In general, triage is grounded by utilitarian theory. |

|

Ethical challenges experienced by UK military medical personnel deployed to Sierra Leone during the 2014–2015 Ebola outbreak |

2017 |

United Kingdom, (Draper, H) |

Semi-structured, interviews, content analysis |

Having previous experience, professional ethics, ethical values in response to the Ebola disease, only one participant introduced the use of humanitarian principles as the basis for actions.

|

|

Ethical considerations for allocation of scarce resources and alterations in surgical care during a pandemic |

2020 |

United States (Rawlings, A) |

brief communication |

Fundamental ethical principles in a pandemic: Beneficence, justice, autonomy, and non-maleficence, the application of these may need to change and include these criteria: maximizing benefits, most lives saved, most life-years gained, equal treatment, lottery system, first-come, first-served, and prioritize the worst off. |

|

Ethical considerations for vaccination programmes in acute humanitarian emergencies |

2013 |

South Africa. (Moodley, K) |

Policy & practice |

The authors lay out the ethical issues in mass vaccination, including beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy and consent, and justice. |

|

Ethical Dimensions of Public Health Actions and Policies with Special Focus on Covid-19 |

2021 |

Egypt (Basma M) |

Review |

The occurrence of Covid-19 highlighted the need for reviewing the existing ethical procedures and protocols for resource allocation. Decision-making regarding resources is a multifaceted process, and various approaches to prioritizing resources have been introduced, which may not necessarily lead to fairness. Principles such as transparency, comprehensiveness, continuity, and responsiveness have been proposed for utilizing specialized ICU equipment. |

|

Ethics for pandemics beyond influenza: Ebola, drug-resistant tuberculosis, and anticipating future ethical challenges in pandemic preparedness and response |

2015 |

Canada (Maxwell J.)

|

Review |

This article delves into the topic of ethical guidelines against the pandemic. The nature of infectious diseases necessitates the development of ethical contingency plans, and experiences from previous influenza pandemics have revealed shortcomings in addressing ethical issues. Current plans do not guarantee effectiveness in managing future infectious disease pandemics. |

|

Ethics of emerging infectious disease outbreak responses: Using Ebola virus disease as a case study of limited resource allocation |

2021 |

United States (Ariadne. A) |

semi-structured interview |

The principle of reciprocity was suggested as the basis for resource allocation for healthcare personnel. In times of resource scarcity, informed consent and the involvement of individuals can be appropriate for resource allocation. |

|

Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19 |

2020 |

United States (Ezekiel J) |

Sounding Board |

The four principles for resource allocation in pandemics – maximizing utility, equal treatment, instrumental value, prioritizing the sickest-serve as ethical foundations in pandemics. These principles, along with their respective instances, form the basis for ethical decision-making during pandemics. Additionally, six recommendations have been proposed for the fair distribution of resources. |

|

Human Dignity as Leading Principle in Public Health |

2018 |

Germany (Sebastian F) |

systematic review |

Three ethical principles of autonomy, utility, and justice in the context of public health and their applications in the policies and programs of Germany were examined. The results indicated that the existing programs align closely with the principles of justice, human rights, and non-maleficence. |

|

A multi-stage stochastic programming approach to epidemic resource allocation with equity considerations |

2021 |

United States (Xuecheng Yin)

|

multi-stage stochastic programming epidemic-logistics model |

Using a mathematical equation, a formula was offered for fair distribution, based on equality and optimization in resource allocation in the case of Ebola. The concepts of equality in capacity and equality in infection are introduced as novel elements in this article. |

|

Resource allocation on the frontlines of public health preparedness and response: report of a summit on legal and ethical issues |

2009 |

United States (Daniel J. Barnett) |

invitation-only Summit and tabletop exercise |

The 10 Summit-derived principles represent an attempt to link law, ethics, and real-world public health emergency resource allocation practices, these 10 principles are grouped into three categories: obligations to community; balancing personal autonomy and community well-being/benefit, and good preparedness practice. |

|

The right to health, public health and COVID-19: a discourse on the importance of the enforcement of humanitarian and human rights law in conflict settings for the future management of zoonotic pandemic diseases |

2021 |

United Kingdom (M.C. Van Hout) |

narrative review |

International humanitarian law, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the right to health, and the Geneva Conventions serve as the bases for providing healthcare services and allocating resources in military conflicts and during the Covid-19 pandemic. Achieving the right to health without discrimination and on an equal basis is a challenge in military conflicts. |

|

Striving for Health Equity: The Importance of Social Determinants of Health and Ethical Considerations in Pandemic Preparedness Planning |

2022 |

Germany (Hanno Hoven) |

commentary |

The ethical principles for public health in pandemics encompass treating people with respect and dignity, reducing harm, cooperation, fairness, reciprocity, proportionality, flexibility, and appropriate decision-making. Some social indicators play a significant role in these principles. |

Ethical principles

Ethical principles serve as a framework for decision-making in resource allocation during pandemics, but their application varies by context [16]. While ethical principles such as equity, justice, autonomy, and non-maleficence are universally recognised, their operationalisation differs depending on the circumstances of the disaster [1, 16, 17]. Common principles include:

Maximising benefits: Prioritising actions that yield the greatest societal good, often through utilitarian approaches [18, 19, 20].

Figure 1. Articles screening and selections flowchart

Reciprocity and instrumental value: Ensuring resources are allocated to those contributing significantly to societal welfare [1, 21, 22].

Respect for individuals: Upholding autonomy, consent, and privacy [1, 2, 22, 17].

Non-maleficence and justice: Avoiding harm and ensuring fair resource distribution [1, 2, 19].

Procedural values: Promoting transparency, accountability, and inclusivity in decision-making [17, 18].

Despite their recognition of these principles, many pandemic response programmes fail to provide operational structures for implementing them [17]. Ethical values are often acknowledged but practical criteria for guiding resource prioritisation are inadequate, leading to inconsistent application [16, 18]. For instance, prioritisation strategies (eg, lottery systems or need-based distribution) vary, and programmes rarely differentiate between ethical values (eg, fairness) and processes (eg, civic participation) [17, 19]. To further clarify two primary ethical frameworks guide resource allocation:

Utilitarianism: This approach focuses on maximising societal benefits, often prioritising the greatest number of lives saved or life-years gained [18, 19, 20].

Non-utilitarian approaches emphasise preserving every life equally, regardless of societal outcomes [20].

Past pandemics reveal that while ethical principles are acknowledged, their translation into practical criteria remains a challenge, necessitating integration with legal frameworks to enhance public health responses [17, 20].

Equity: Equity is a cornerstone of ethical resource allocation, intersecting with the right to health and social determinants of health [24]. Three distinct approaches to equity are identified in resource allocation: Parity: equal access to medical treatment for all individuals [23]. Proportionality: distributing resources based on existing disparities [23]. Prioritisation: allocating resources to those with the greatest clinical need [18, 23].

Equity is manifested in various dimensions, including capacity, infection control, and intergenerational considerations [24, 17]. However, achieving true equity is complex. For example, the lottery system has been found more effective than first-come, first-served approaches in promoting fairness, but overemphasising equity may exacerbate disease spread or increase costs [1, 20, 19, 24]. Contextual factors, such as security conditions during conflicts, further complicate equitable distribution [2].

Inequities in health, particularly during pandemics, arise from disparities in exposure, infection, treatment, and resource access, often influenced by race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status [24]. To address this, triage protocols emphasise distributive justice, ensuring resource allocation that avoids discrimination based on non-clinical factors (eg, race, gender, disability) [18]. Universal health coverage is proposed as a mechanism to reduce health inequities, ensuring balanced access to critical resources for both pandemic-affected and other patients [24].

Justice and fairness: Justice, closely tied to equity, is a central ethical consideration in resource allocation [2, 17, 18, 19]. It is categorised into distributive justice ie, fair allocation of limited resources, ensuring benefits and burdens are equitably distributed [2, 18,]; and procedural justice ie, engaging stakeholders in transparent and inclusive decision-making processes [2, 17].

Justice emphasises reciprocity, maximising protection against diseases, and ensuring equal access to resources [17, 21]. Social justice requires equitable access to resources, while procedural fairness demands social participation in allocation decisions [17]. However, inequities often persist, conflicting with principles of fairness, particularly when influenced by non-clinical factors [24].

Humanitarian principlesHumanitarian principles are deeply connected to the management, distribution, and allocation of resources. The International Humanitarian Law (IHL), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and United Nations refugee laws are among the guiding documents that uphold the principles of the humanitarian approach in times of crises, affirming the right to equitable health access for individuals [7, 25].

Humanity: Central to the principle of humanity, human dignity recognises the inherent value of every individual. It comprises two levels viz unconditional respect for individuals as a moral benchmark and ethical principles of utility, autonomy, non-maleficence, and justice, which align with pandemic responses. Patient rights must correspond with human rights, foundational to international laws, emphasising dignity [21]. IHL, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and UN refugee laws support access to healthcare in crises [7, 25].

Impartiality: Impartiality ensures healthcare is provided based solely on need, without bias. Medical teams in conflict zones must assist all parties equitably [26]. Governments are required to deliver sufficient, non-discriminatory healthcare services [22]. Race is associated with inequities in resource distribution, and lack of fairness and impartiality [23]. Societal needs must be met without discrimination based on race, culture, nationality, religion, gender, residence, or financial status [17].

Neutrality: Neutrality mandates that medical aid in conflict zones be delivered without favouring any side [26]. UN regulations for resource management in crises, including pandemics, include the right to medical care as a human right [25]. Neglecting neutrality and other principles may impair effectiveness in humanitarian efforts [24].

Independence: Independence enables autonomous humanitarian action, free from external influence. Excluding this principle may limit the role of humanitarian organisation in healthcare provision efforts [24]. Aligning patient rights with human rights, as outlined in international laws, ensures that aid delivery remains independent [21].

FacilitatorsImplementing humanitarian and ethical principles in resource allocation during pandemics is enhanced by facilitators that promote fairness, transparency, and efficiency in crisis response. Themes related to these facilitators are presented below, elucidating key strategies.

Guideline-driven frameworks: Standardised guidelines provide a structured approach to ethical and humanitarian resource allocation. Documents like the Sphere Handbook and the Health Cluster guide, grounded in beneficiary-focused principles, guide the provision of humanitarian aid in pandemics. Principles such as suitability ensure that actions are appropriate for the context and stakeholders involved. Sustainability prioritises long-term benefits and resource preservation. Informed key persons refer to stakeholders with relevant expertise or influence who improve resource allocation decisions by providing context-specific insights. Supply management focuses on efficiently handling resources to avoid waste or shortages. Licensing knowledge ensures compliance with legal and regulatory requirements. Additionally, transparency promotes openness in decision-making, comprehensiveness ensures that all relevant factors are considered, and accountability holds individuals and organisations responsible for their actions. Together, these principles create a clear and effective guide for ethical and humanitarian decision-making. Triage methods and standards of care, informed by scientific evidence, ensure fair and effective distribution of limited resources, enhancing the operationalisation of these principles [2, 8, 24].

Community engagement and trust: Community involvement strengthens resource allocation by fostering trust and cultural alignment. Community perceptions significantly influence the success of response efforts, and active participation improves public understanding of allocation decisions. Valuing cultural and social norms, reducing rumours, respecting individual autonomy, and establishing culturally sensitive satisfaction mechanisms builds trust between communities and response teams, reinforcing ethical principles and ensuring that humanitarian actions resonate with local values [1, 17, 19, 22].

Stakeholder collaboration and transparency: Collaboration among diverse stakeholders and transparent decision-making processes alleviate moral burdens and enhance trust. Involving triage teams and ethics groups in collective decision-making prioritises societal needs over individual preferences. Transparent methods, coupled with active engagement of vulnerable groups in decision-making, strengthen community trust and uphold ethical standards, ensuring allocation decisions are perceived as fair and inclusive [1, 8, 20].

Legal and educational integration: Integrating ethical principles into legal frameworks and educational initiatives supports equitable allocation. Embedding patient rights and ethical considerations into national laws, while incorporating public opinion and cultural standards, creates robust frameworks for resource allocation. Crisis management laws clarify priorities within and beyond national borders, while educational programmes foster public participation and awareness, aligning allocation practices with humanitarian principles and societal values [17, 18, 21].

Problems and challengesImplementing humanitarian and ethical principles in resource allocation during pandemics faces significant obstacles, reflecting the complexity of balancing fairness and efficiency in crisis settings. In the following, themes related to these challenges are presented.

Decision-making pressures: Healthcare professionals face intense pressure arising from resource scarcity and time constraints, leading to decisions that may deviate from ethical principles, compounded by significant psychological burdens. For example, prioritising based on the severity of harm may seem ethically sound, but it may not be justifiable in terms of resource efficiency during resource shortages. Similarly, criteria like “first-come, first-served” have not led to equal resource distribution because individuals who lack the means to access and relocate are deprived of access to resources [19]. Misinformation distorts public and professional understanding of equity, eroding trust and complicating fair allocation processes. In some instances, it has been witnessed that, despite the principle of equity, individuals’ wealth and social class have influenced their access to resources [1, 19, 22].

Contextual and structural barriers: Infectious disease outbreaks are significantly impacted by contextual and structural barriers. Insecurity, instability, displacement, and poverty disrupt observance to the right to health, despite United Nations conventions [27]. These conditions, coupled with social health disparities in low-income and educationally disadvantaged areas, heighten vulnerability and limit access to resources. Incomplete data on social health indicators further complicate equitable resource allocation and priority-setting for communicable diseases, undermining ethical and humanitarian principles [27, 28].

Inefficiencies in humanitarian and ethical operational criteria: Humanitarian criteria — humanity (protecting life and dignity), impartiality (aid based on need), neutrality (avoiding bias), and independence (autonomous decision-making), lack effective operational frameworks in resource-scarce settings. These are hindered by inadequate needs assessments, incomplete data, external pressures, and political influence. Ethical criteria are also inefficient: prioritising severity of harm fails under scarcity; “first-come, first-served” approaches exclude disadvantaged groups; and allocating resources to terminally ill patients may prolong suffering without benefit [19, 21, 23, 25, 27].

Triage protocol inadequaciesTriage protocols, often developed without public input or sufficient testing, fail to incorporate key societal values such as equity, transparency, and fairness. Excluding public engagement can result in protocols that disproportionately disadvantage vulnerable populations. This lack of alignment with societal values leads to public distrust and creates challenges in ethical implementation, especially when resource shortages require difficult allocation decisions [18, 20].

Discussion

Humanitarian principles are foundational criteria for infectious disease outbreak responses, guiding health interventions to align with human rights and ensure equitable access to resources. These principles mandate that resource allocation in pandemics be need-based, free from discrimination based on political, racial, gender, or income-related factors, and accessible to all, as outlined in international guidelines [3]. However, this study has demonstrated that there are challenges in consistently applying these principles during communicable disease emergencies, with ethical considerations and equity frequently serving as primary criteria for resource allocation decisions [1, 2, 9, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26]. Moreover, during patient selection in outbreaks, healthcare professionals often rely on medical ethics principles, such as beneficence and non-maleficence, to prioritise individual patient outcomes [29]. Nevertheless, the close relationship between humanitarian principles and ethical values is evident, as both aim to uphold fairness and dignity, though their practical application varies due to contextual constraints [25].

The global shortage of critical equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic, including ventilators and personal protective equipment, highlighted significant challenges in applying ethical principles effectively [20]. However, it seems that there is a need for a structured strategy that combines humanitarian principles, ethical decision-making, and practical solutions to address both individual and population-level needs in a balanced and equitable manner. In this context, coordination mechanisms, such as those established by the Health Cluster standards, are often formed when existing mechanisms fail to meet needs in alignment with humanitarian principles or when government actions deviate from international standards, as evidenced by instances of restricted aid access [3]. Despite these considerations, this study revealed that practical principles tend to focus more on ethics and equity in hospital units and healthcare service providers [1, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26]. Since resource allocation ultimately impacts individuals, both ethical and humanitarian principles are relevant at individual and group levels, requiring careful integration to ensure fairness [25]. While humanitarian principles are rooted in ethics, the broader scope of ethical considerations encompasses additional dimensions, including justice, fairness, and individual rights, which extend beyond the scope of humanitarian principles alone [25].

The principle of impartiality, which requires aid delivery without bias in politically charged contexts, can conflict with ethical codes, particularly when providing aid to groups involved in conflicts. For instance, offering assistance to terrorist groups may be ethically problematic, as it can aggravate violence [26]. This tension becomes acute in infectious disease outbreaks, where denying aid risks accelerating transmission, while indiscriminate aid may empower violent actors, highlighting the complexity of applying humanitarian principles in such settings [25, 26, 30].

Equity is frequently framed within humanitarian principles, with studies suggesting that its implementation supports fair resource allocation [3]. Researchers identify equity as a key ethical criterion for resource allocation, though achieving consensus on its application remains challenging, due to varying definitions and priorities [19, 23, 24]. In Figure 2, a schematic representation, derived from this study, illustrates the relationships among ethics, humanitarian principles, equity, justice, and fairness in the context of infectious disease outbreaks, highlighting their overlapping yet distinct roles in guiding allocation decisions. These interconnections emphasise the need for a comprehensive approach that integrates these concepts to address diverse needs effectively.

Figure 2. The relationship among ethics, humanitarian principles, equity, justice, and fairness in pandemics in the present study

While the four principles have been introduced as the basis for ethical actions in medical sciences, there is no robust consensus on suitable criteria for resource allocation. Some believe that fair distribution requires a multi-criteria framework, where resource allocation depends on the type of resources and the required services. Therefore, it is necessary to assign weights to the existing criteria to balance these criteria in different situations [22]. Studies advocate for a multi-criteria framework, where allocation decisions depend on resource type, service needs, and contextual factors, requiring weighted criteria to balance competing priorities [22]. For example, prioritising ventilators based on clinical severity may align with ethical principles but may not address broader population needs, necessitating a balanced approach [22].

Differences in ethical values and processes, as well as distinctions between justice in methodology (designing fair processes) and justice in execution (implementing them equitably), highlight the need for structured approaches to apply humanitarian principles effectively [2, 17].

In this regard, frameworks like the Health Cluster and Sphere Standards provide essential guidance for resource management, but their standard conditions may not fully address pandemic-specific challenges in resource-limited settings, requiring context-specific adaptations [2]. Tools such as WHO HeRAMS (Health Resources Availability Monitoring System) and HNO (Humanitarian Needs Overview) support humanitarian responses by assessing needs and prioritising vulnerable populations, aligning with ethical and humanitarian principles [30, 31]. However, their effectiveness in pandemics is limited by insufficient real-time epidemiological data and poor integration with disease surveillance systems, as evidenced by challenges in tracking infection rates during outbreaks [32]. The literature recommends enhancing data integration, proactive preparedness, and community involvement to improve the impact of these tools, ensuring more equitable and effective resource allocation [32].

As mentioned, equity is one of the key criteria in resource allocation decisions, and some argue that equity in pandemics encompasses both equity in capacity and equity in infection, meaning that resource allocation should ensure minimal disparities in infection rates across different regions [18]. Regions with limited resources require significant allocations, yet these may yield limited effectiveness, complicating prioritisation efforts [24]. The literature highlights that prioritising resources based on humanitarian principles involves complex decisions, requiring indicators like service coverage, incidence rates, and preserved life years, supported by triage guidelines and international conventions [33]. For example, prioritising high-risk groups like the elderly during Covid-19 required balancing immediate needs with long-term outcomes [33]. The principle of reciprocity, which involves allocating resources to healthcare workers, is critical, as seen in Liberia’s Ebola outbreak, where 8% of victims were healthcare workers, highlighting the need to protect frontline responders [1, 21, 20]. This example illustrates that relying solely on humanitarian principles without integrating ethical considerations, such as fairness to healthcare workers, is insufficient to address pandemic challenges effectively.

Therefore, structured processes, including legal frameworks, international conventions, and community engagement, are essential for implementing humanitarian and ethical principles [2, 17]. In this regard, laws and anti-corruption measures play a significant role in ensuring accountability and fairness, as seen in regulatory frameworks that govern vaccine distribution [33].

RecommendationsIt is recommended that, in order to apply ethical and humanitarian principles, pandemic management be supported by inclusive processes and robust tools to ensure equitable and effective responses to complex infectious disease emergencies. Multi-criteria frameworks should also be applied to balance competing priorities, such as allocating critical care resources and implementing preventive measures, to achieve fairer outcomes. In addition, strengthening community engagement is essential for fostering trust and promoting culturally sensitive interventions. Finally, adopting evidence-based tools, such as standardised triage protocols, is recommended to enhance transparency, consistency and accuracy in allocation decisions.

Conclusion

The present study shows that while humanitarian principles serve as the foundation for international responses to emergencies, their practical application in resource allocation during pandemics, particularly in relief and medical aid, remains limited. The findings also highlight the necessity to integrate ethical principles with humanitarian values, as ethics provide a broader framework that complements humanitarian principles in emergency response.

To enhance the implementation of humanitarian principles in pandemics, it is essential to develop structured processes tailored to these challenges. Pre-emergency education and global awareness programmes are crucial for ensuring the commitment of individuals and institutions involved in resource allocation. Strengthening international coordination is also necessary, with organisations like the World Health Organisation playing a key role in guiding and overseeing resource allocation. Moreover, ensuring justice and equity in access to resources requires the addressing of structural, legal, and procedural aspects alongside humanitarian principles.

By considering these factors, resource allocation in future emergencies can be more effective, with stronger integration of humanitarian and ethical principles. Future research should focus on developing quantitative models that utilise artificial intelligence and mathematical methods to enhance resource allocation based on humanitarian principles. Existing models should also be reviewed to ensure they align with justice, equity, and ethical considerations. Also, further investigation into neutrality and its ethical implications in resource allocation remains necessary.

Authors: Mohammad Reza Fallah Ghanbari ([email protected]), Doctoral Candidate, Health in Disasters and Emergencies, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBMU), Tehran, IRAN; Mehdi Safari (corresponding [email protected]), Assistant Professor of Health in Disasters and Emergencies Department, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBMU), Tehran, IRAN; Katayoun Jahangiri ([email protected]), Professor of Health in Disasters and Emergencies Department, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBMU), Tehran, IRAN; Zohreh Ghomian ([email protected]), Associate Professor, Health in Disasters and Emergencies Department, School of Public, Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences(SBMU), Tehran, IRAN; Mohammad Ali Nekooie ([email protected]), Associate Professor , Department of civil engineering, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Alborz university, Alborz Province, IRAN.

Conflict of Interest: None declared Funding: None

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank the authorities of Shahid Beheshti University Medical Sciences for their facilitation and support.

To cite: Fallah Ghanbari MR, Safari M, Jahangiri K, Ghomian Z, Nekooie MA. Ethical and humanitarian considerations in allocating healthcare resources during infectious disease emergencies: A scoping review. Indian J Med Ethics. 2026 Jan-Mar; 11(1) NS: 10-18. DOI: 10.20529/IJME.2026.003

Submission received: June 15, 2024

Submission accepted: October 7, 2025

Manuscript Editor: Rakhi Ghoshal

Peer Reviewers: Priyansh Nathani, Sunu C Thomas

Copyright and license

©Indian Journal of Medical Ethics 2025: Open Access and Distributed under the Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits only noncommercial and non-modified sharing in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Nichol A, Antierens A. Ethics of emerging infectious disease outbreak responses: Using Ebola virus disease as a case study of limited resource allocation. PLoS One. 2021 Feb 1;16(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246320

- Moodley K, Hardie K, Selgelid M, Waldman R, Strebel P, Rees H, et al. Ethical considerations for vaccination programmes in acute humanitarian emergencies. Bull World Health Organ. 2013 Apr;91(4);290-7. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.12.113480

- World Health Organization. Health cluster guide: a practical handbook. 2020 Sep 4 [cited 2025 Nov 5]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/334129

- Lin C, Franco J, da Costa Ribeiro S, Dadalto L, Letaif L. Scarce Resource Allocation for Critically ill Patients During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Public Health Emergency in São Paulo Brazil. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2021 Jan; 20(76)1–4. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2021/e2191

- Dao B, Savulescu J, Suen J, Fraser J, Wilkinson D. Ethical factors determining ECMO allocation during the Covid-19 pandemic. BMC Med Ethics. 2021 Jun 1;22(1).70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00638-y

- Khoo J, Lantos D. Lessons learned from the Covid-19 pandemic. Acta Paediatr. 2020 Jul;109(7):1323-1325. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15307

- World Health Organization (WHO), and United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Right Factsheet 31: The Right to Health. 2008 Jun 1 [Cited 2025 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/publications/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-no-31-right-health

- Guo Y, Ye Y, Yang Q, Yang K. A multi-objective INLP model of sustainable resource allocation for long-range Maritime search and rescue. Sustainability. 2019;11(3):929. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030929

- Simm K. Ethical Decision-Making in Humanitarian Medicine: How Best to Prepare? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021 Aug;15(4):499-503. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.85

- Dubey R. Design and management of humanitarian supply chains: challenges, solutions and frameworks. Ann Oper Res. 2022 Dec 1;319(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-022-05021-7

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method. 2005: 8(1); 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien K, Colquhoun H, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct 2;169(7)467-473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. What are Humanitarian Principles? 2012 Jun 30[Cited 2025 Nov 5]. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/ocha-message-humanitarian-principles-enar

- Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco A, Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews . JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Joanna Briggs Institute. 2024. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-24-09

- Armstrong R, Doyle J, Waters E. Cochrane Update. ‘Scoping the scope’ of a Cochrane review. J Public Health. 2011 Mar; 33(1): 147–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr015

- Smith M, Silva D. Ethics for pandemics beyond influenza: Ebola, drug-resistant tuberculosis, and anticipating future ethical challenges in pandemic preparedness and response. Monash Bioeth Rev. 2015 Jun-Sep;33(2-3):130-47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40592-015-0038-7

- Barnett D, Taylor H, Hodge J, Links J. Resource allocation on the frontlines of public health preparedness and response: report of a summit on legal and ethical issues, Public Health Rep. 2009 Mar-Apr; 124(2), 295-303. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490912400218

- Fiest K, Krewulak K, Plotnikoff K, Kemp LG, Parhar KKS, Niven DJ, et al. Allocation of intensive care resources during an infectious disease outbreak: a rapid review to inform practice. BMC Med. 2020 Dec;18(1):404. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01871-9

- Rawlings A, Brandt L, Ferreres A, Asbun H, Shadduck P. Ethical considerations for allocation of scarce resources and alterations in surgical care during a pandemic. Surg Endosc. 2021 May;35(5):2217-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07629-x

- Emmanuel E, Persaud G, Upshur R, Thom B, Parker M, Glickman A, et.al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 May 21; 382(21): 2049-2055. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsb2005114

- Winter SF, Winter SF. Human dignity as leading principle in public health ethics: A multi-case analysis of 21st century German health policy decisions. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018 Mar;7(3):210-24. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2017.67

- Hoven H, Dragano N, Angerer P, Apfelbacher C, Backhaus I, Hoffmann B, et al. Striving for Health Equity: The Importance of Social Determinants of Health and Ethical Considerations in Pandemic Preparedness Planning. Int J Public Health. 2022 Apr ;67. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604542

- Saleh BM, Aly EM, Hafiz M, Gawad RMA, Kheir-Mataria WAE, et.al. Ethical Dimensions of Public Health Actions and Policies with Special Focus on Covid-19. Front Public Health. 2021 Aug 2; 9:649918. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.649918

- Yin X, Büyüktahtakın I. A multi-stage stochastic programming approach to epidemic resource allocation with equity considerations. Health Care Manag. 2021 Sep;24(3):597-622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10729-021-09559-z

- Draper H, Jenkins S. Ethical challenges experienced by UK military medical personnel deployed to Sierra Leone (operation GRITROCK) during the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak: a qualitative study. BMC Med Ethics. 2017 Dec;18(1):77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-017-0234-5

- Gordon S, Donini A. Romancing principles and human rights: Are humanitarian principles salvageable? Int Rev Red Cross. 2016; 97)897-898(, 77-109. https://doi:10.1017/S1816383115000727

- Van Hout M, Wells J. The right to health, public health and Covid-19: a discourse on the importance of the enforcement of humanitarian and human rights law in conflict settings for the future management of zoonotic pandemic diseases. Public Health. 2021 Mar; 192:3-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.01.001

- Hoven H, Dragano N, Angerer P, Apfelbacher C, Backhaus I, Hoffmann B, et al. Striving for Health Equity: The Importance of Social Determinants of Health and Ethical Considerations in Pandemic Preparedness Planning. Int J Public Health. 2022 Apr;67 https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604542

- Iserson K. Ethical principles-emergency medicine. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2006 Aug;24(3):513-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2006.05.007

- Nickerson J, Hatcher J, Adams O, Attaran A, Tugwell P. Assessments of health services availability in humanitarian emergencies: a review of assessments in Haiti and Sudan using a health systems approach. Confl Health. 2015 Jun; 9:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-015-0045-6

- Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO). Global Protection Cluster. [Cited 2025 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www.globalprotectioncluster.org/node/1026

- Mala P, Abubakar A, Takeuchi A, Buliva E, Husain F, Malik MR, et al. Structure, function and performance of Early Warning Alert and Response Network (EWARN) in emergencies in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Int J Infect Dis. 2021 Apr; 105:194–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.002

- Fallah Ghanbari MR, Jahangiri K, Safari M, Ghomian Z, Nekooie MA. Experts’ Views on Factors Influencing Resource Allocation for Infectious Disease Emergencies Based on Humanitarian Principles: A Qualitative Study. AJPM Focus. 2024 Oct;4(1):100286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focus.2024.100286