OBITUARY

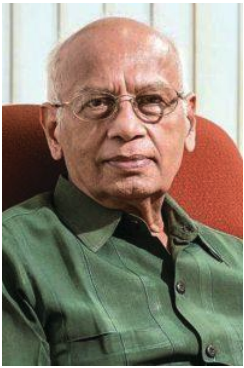

Dr Marthanda Varma Sankaran Valiathan (1934-2024)

Sunil K Pandya

Published online first on July 22, 2024. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2024.045

Childhood and education

Marthanda Varma Sankaran Valiathan was born in Mavelikara in the district of Alappuzha, of Travancore State (now Kerala). In an interview, he credited his parents for his interest in Sanskrit, Malayalam, English, music and ethical conduct. There were several physicians in his family. One of his uncles, Dr VS Valiathan, had studied in Edinburgh in 1902. He decided to follow in his uncle’s footsteps.

After studying in the local school, he went to Trivandrum (now Thiruvananthapuram) where he studied science at University College.

His postgraduate studies were in Liverpool. He obtained the Fellowship of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons of Edinburgh and of England in 1960. He also obtained the M.Ch. in Liverpool.

On his return to India, he worked for a while on the faculty of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh. Wishing to specialise, he travelled to the Johns Hopkins Hospital and Georgetown University Hospital in the USA, for training in cardiac surgery. He was forever grateful to his two mentors — Dr Vincent Gott and Dr Charles Hufnagel. They instilled in him the urge to innovate [1].

Return to India

On returning to India in 1971, he could only obtain an ad hoc appointment to the surgical staff of Safdarjung Hospital in Delhi and could do neither cardiac surgery nor research.

Dr Valiathan moved to the Indian Institute of Technology in Madras (now Chennai) as a visiting professor but found he was spending most of his time in teaching [1].

This is when he was invited by Achutha Menon, then Chief Minister of Kerala, to come to Trivandrum and take charge of the newly created Sree Chitra Medical Centre, intended to be a specialties hospital and teaching institution. The royal family of Travancore had gifted a multistoreyed building to the people and Government of Kerala in 1973 to house the centre. It was close to the Trivandrum Medical College and Hospital but independent of them.

Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology, Trivandrum

As its first Director, Dr Valiathan developed facilities for the treatment of diseases of the cardiovascular and nervous systems. He set a high standard for those who followed him.

He soon faced a problem plaguing all other cardiovascular surgeons in the country — a total dependence on foreign manufacturers for very expensive cardiac valves and other devices. He and his team decided to design and make mechanical valves with a tilting-disc design. He started the Biomedical Technology Wing of the Sree Chitra Institute at the Satelmond Palace, on the banks of the river Karamana, nearly 11 km away from the hospital. This, too, was a gift from the royal family [1].

Dr Valiathan’s team soon developed the valve and arranged to get it manufactured commercially for the benefit of surgeons elsewhere in the country. Many other essentials, including the bag for collecting donated blood, were to follow from this laboratory.

The concept of amalgamating medical sciences and technology within a single institutional framework was regarded as sufficiently important by the Government of India, led by Prime Minister Morarji Desai, for it to be declared an Institute of National Importance. It was now named Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology, Trivandrum and placed under the Department of Science and Technology by an Act of Parliament.

As Director, Dr Valiathan functioned under the Governing Body of the Institute, the Presidents of which were far-sighted, eminent scientists and statesmen.

On retiring from the institute in 1991, he was appointed the first Vice-Chancellor of Manipal University. He held this office till 1999.

Medical ethics

As indicated in the first paragraph above, the principles of ethical behaviour were ingrained in him at home. As he entered the world of medicine in India, he was troubled by the jettisoning of these principles by many members of the profession. His attempts at incorporating ethics as part of the curriculum bore fruit when The Centre for Bioethics was established in the Manipal Academy of Higher Education. This centre now has five professors on its rolls.

In his essay in Current Science (1992), Dr Valiathan took off from where George Bernard Shaw had left off, and revisited the doctor’s dilemma. Whilst the entire essay deserves study, I particularly call your attention to the final section titled “The ethical question” [2]. I shall not rob you of the impact of this essay by disclosing any more details.

Dr Valiathan and the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics

At our request, Dr Valiathan organised a discussion in his office in Manipal on the need to do research and prepare a database on discussions on medical ethics in ancient and medieval India. Dr VR Muraleedharan, Dr N Sreekumar (both from IIT, Madras), Dr Amar Jesani and I were the participants.

He applauded the National Bioethics Conferences and participated in those held in 2007 (where he honoured Dr Anil Pilgaonkar) and in 2014 (where he was honoured by Dr Thelma Narayan).

Dr Valiathan’s paper in the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics in 2008 was on bioethics and ayurveda. It had formed his inaugural address at the National Bioethics Conference in 2007 and focused on health and disease, patients, professional conduct and general conduct as discussed in the ayurvedic classics [3].

He returned to these subjects again and again.

Ayurveda and the history of medicine

In 1999, he was awarded a Senior Fellowship by the Homi Bhabha Council to pursue a study of Caraka. He did so under the respected ayurvedic physician and scholar, Sri Raghavan Thirumulpad in Kerala who was in his 80s. He wrote “I would inform him in advance that I would be coming with notes on my understanding of three to five chapters of the Samhita—sometimes only one—so that he too would have looked at the text. I would discuss what I had understood; he would point out my mistakes, the need for greater clarity, for abridgment, or expansion, etc. He would also share with me related ideas and his own experience, which was invaluable. They were highly enlightening discussions.” [4]

This resulted in the publication of The Legacy of Caraka. He dedicated this book to his parents.

Later, as National Research Professor, he studied the works of Susruta and Vagbhata and completed the series of volumes on the three pillars of Ayurveda. He later added two more volumes on Ayurveda — An introduction to Ayurveda in 2013, and Ayurvedic Inheritance in 2023.

Dr Valiathan explained in an interview why he turned to Ayurveda:

I think that my upbringing in an Ayurveda-friendly environment has a lot to do with it. Our family used to consult a reputed Ayurvedic physician nearby for any illness except for those warranted surgical intervention. However, all through my active professional career in modern medicine, Ayurveda had disappeared from my sight only to resurface in the 1990s, a time when the feeling that nothing in my cardiac surgical practice, or indeed in the modern medicine, had been contributed by an Indian started to dominate my thoughts. The fact that there had been no global contribution by an Indian in areas like causation of a disease, a drug, a surgical technique, a technology, a prophylactic regime in medicine disturbed my mind… I started to probe the history of our country to find out whether there was a period when we were creative and innovative. It led me to the life and times of scholarly sages ‒ Charaka, Susruta, and Vagbhata. [1]

During the remaining years of his life, Dr Valiathan kept emphasising that ayurveda is not only the mother of medicine but also of all life sciences in India. He strove for a common ground where physicists, chemists, immunologists and molecular biologists interacted with ayurvedic physicians. He felt that these were the interdisciplinary areas where advances would take place. He conducted seminars, workshops and delivered talks on this and related subjects.

He was especially fond of referring to ethics as it was taught by the three ayurvedic pioneers he had written about. In The Legacy of Caraka, he imagined the sage addressing our generation of physicians:

You would do well to remember that you are on new ground where knowledge is preferred to wisdom, where profit is confused with happiness and success is mistaken for triumph. You should look at where you are and where you are headed. Do not expect miracles of me. I have none to offer. I have left you a heritage which, though all-embracing, exists within a world of unknown reserves of knowledge, experience and faith. It behoves you to explore the trackless land, even as your forefathers did, and enhance your power to heal. But far from glorifying knowledge, you should celebrate good conduct, free from extremes and errors of judgement. Ayurveda owes its call not to selfish goals or worldly pleasure, but to compassion for fellow beings. In seeking to know my legacy, you have but seen the leaves of a universal tree, too vast for your eyes. May your sight grow and your quest never end. [5]

Accolades, awards

He was a respected member of several national academic organisations such as the Indian National Science Academy, Indian Academy of Sciences, Indian National Academy of Engineering, the World Academy of Sciences, American College of Cardiology, Royal College of Physicians of London, International Union of Societies of Biomaterials and Engineering, and presided over some of them. He received numerous accolades and awards including Padma Vibhushan (2005), Dr BC Roy National Award, the Jawaharlal Nehru Award, JC Bose Medal, and Dr Samuel P Asper Award for International Medical Education from Johns Hopkins University. France appointed him Chevalier of the Order of Palmes Académiques. He was Hunterian Professor of the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

He died on 17 July 2024, aged 90, in Manipal Hospital.

References

- Anonymous: Every Morning Brings a Noble Chance – An interview with Dr. M.S. Valiathan. Agappe blog. [Cited 2024 Jul 19]. Available from: https://www.agappe.com/in/blog-details/every-morning-brings-a-noble-chance-an-interview-with-dr-m-s-valiathan.html.

- Valiathan MS. Doctor’s dilemma – a postscript. Curr Sci. 1992 Apr 10[Cited 2024 Jul 22];62:495-497. Available from: https://www.currentscience.ac.in/Volumes/62/07/0495.pdf

- Valiathan MS. Bioethics and ayurveda. Indian J Med Ethics. 2008 Jan-Mar;5(1):29-30. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2008.011

- Joshi K. Insights into Ayurvedic biology—A conversation with Professor M.S. Valiathan. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2012 Oct-Dec; 3(4): 226–229. https://doi.org/10.4103%2F0975-9476.104450

- Valiathan MS. The Legacy of Caraka. Orient Blackswan;2003. 634 pp