COVID-19

A qualitative inquiry into stigma among patients with Covid-19 in Chennai, India

Vijayaprasad Gopichandran, Sudharshini Subramaniam

Published online first on March 1, 2021. DOI:https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2021.013Abstract

Introduction: The Covid-19 pandemic has left a serious impact on the lives of people globally. One key social consequence of the infection has been the stigma associated with it.

Objectives: This study was conducted to explore the lived experiences of stigma among persons who have recovered from Covid-19 in Chennai, India.

Methods: In depth telephonic interviews were conducted among 12 persons who had recovered from Covid-19 in Chennai. The participants were encouraged to narrate their experiences of stigma. The telephonic interviews were transcribed and coded by both the researchers. The codes were then grouped into meaningful themes and the lived experiences of stigma described with the help of rich narrative quotes.

Results: The common manifestations of stigma were exclusion from public spaces and essential services, loss of livelihood, loss of social support and, in an extreme case, physical violence. The stigma was also manifested in health facilities in the form of neglect, and rude and insensitive treatment of patients. The factors that aggravated the stigma included fear of infection, lack of information, legitimisation of segregation by forced public health interventions, involvement of police in contact tracing, and isolation. Stigma was associated with psychosocial consequences such as loneliness, uncertainty, anxiety, anger, and humiliation. Demonstration of empathy, advances in communication technology, solidarity in communities and protecting confidentiality could potentially mitigate stigma. The intersectionality of age, gender, poverty, and disability worsened the experience of stigma.

Conclusions: People who had recovered from Covid-19 experienced various degrees of social stigma. The future impact of the pandemic will depend strongly on the ability of health systems to address stigma.

Key words: Covid-19, stigma, social isolation, segregation, intersectionality, in depth interviewIntroduction

The Covid-19 pandemic spread rapidly throughout the world, starting from late 2019 (1). The SARS CoV2 virus, by virtue of being highly infectious and leading to a large proportion of subclinical and mild infections, became a suitable candidate for creating an outbreak of pandemic proportions (2). The pandemic caused serious disruptions in normal life despite the mortality rate being low. The subsequent restrictive lockdowns seriously hampered the global economy (3). The fragile health systems of low- and middle-income countries faced a major shock, which worsened the outcomes for even moderately severe infections. One of the important social impacts of this pandemic was the stigma associated with the disease (4).

From a sociological perspective, stigma is defined as the phenomenon in which the stigmatised person possesses an attribute that reduces their value in society and degrades them in that context (5). Many diseases are associated with stigma including tuberculosis, leprosy, HIV/AIDS and mental illnesses. Several scholars have attempted to understand and describe the lived experience of stigma associated with these illnesses (6). One of the major consequences of stigma is a refusal to seek care for the illness for fear of being stigmatised (7). This has seriously impaired efforts to eliminate diseases like tuberculosis and leprosy as people hesitate to seek care and undergo treatment for these conditions (8). Stigma has also been associated with poor outcomes of disease due to lack of appropriate access to care (9).

Covid-19 has been associated with different patterns of stigma, such as stigma based on region, religion, occupation and persistent stigma even on recovering from the illness (10). The infection originated in China and so, early during the pandemic, people of Asian descent were stigmatised all over the world (11). In India there were reports of people from North Eastern states facing discrimination as they have Asian physical characteristics (12). There was a large religious gathering in New Delhi, following which many clusters of Covid-19 were identified throughout the country (13). This led to a severe form of stigmatisation of people belonging to that religion. Doctors, nurses and healthcare providers were stigmatised based on their high-risk occupation and were evicted from their rented houses and excluded from public spaces (14). Healthcare providers who died due to Covid-19 were denied space for burial or cremation due to fear of contagion (15). There were also reports of stigmatisation of people who had recovered from Covid-19, on returning home (16).

Research on stigma and Covid-19 is emerging from various contexts all over the world. A case study reported the lived experiences of stigma among Covid-19 patients in India (17). A qualitative study from South Africa highlighted the role of misinformation in the worsening of stigma (18). A study from Nepal revealed stigmatisation of frontline health workers (19). A quantitative survey of 91 people who had survived Covid-19 infection in Kashmir, India, showed a high level of enacted and externalised stigma ie stigma which is a consequence of social interactions of the infected persons (20). However, there are not many qualitative interview-based studies. We conducted this study as a qualitative inquiry into the lived experiences of stigma among persons diagnosed with Covid-19 at various stages of their disease from the point of onset of illness, through diagnosis, care seeking, hospitalisation, isolation, recovery, and discharge, to returning home after recovery.

Methods

We conducted in-depth interviews among purposively selected persons who had been diagnosed with Covid-19 and had recovered from the illness. Both of us, VG (male) and SS (female) conducted the in-depth interviews over mobile phone in order to maintain physical distancing and reduce the risk of transmission of the virus. Both of us are trained in qualitative research methods and interview techniques. We were actively involved in Covid-19 control activities in our respective institutions. While SS was involved in coordinating public health activities, VG was delivering clinical services in Covid-19 outpatient settings.

We identified the participants from the isolation ward and outpatient departments of our respective hospitals. A rapport was established between us, the researchers and the participants, before the interviews. To enable the qualitative inquiry process, we selected only those patients whom we perceived as capable of providing rich descriptive narratives.

Initially, our sample covered eight individuals, including both men and women, from the two health facilities. It is worth noting that two of these participants were interns who got infected while working in the Covid-19 wards. Their narratives are unique in that they have a dual perspective, first as healthcare providers, and second, as survivors of Covid-19 and the stigma associated with it. We performed a preliminary coding at the end of eight interviews and identified a few emerging themes. We then conducted four more interviews from among specific participant groups for better insights into the intersectionality of various social factors influencing stigma. From the preliminary analysis, we found that the narratives of women, the elderly, and persons with disabilities were different from those of men, the young, and persons without disabilities. In order to achieve saturation of themes and comprehensiveness of the experiences of stigma, we purposively sampled an elderly woman from a non-poor background, a young man from a non-poor background without disability, and a young woman from a poor background with disability. We conducted one more additional interview to confirm data saturation, which had started appearing from the 10th interview.

We took prior permission from the selected participants to make phone calls and conduct the interviews. We called them and administered a verbal informed consent. Each interview lasted between 20 and 40 minutes. The interviews were conducted in the Tamil language. Since we conducted the interviews telephonically, we could protect participant privacy. The other advantages of telephonic interviews include convenience in time, perceived anonymity, reduced distraction and reduced self-consciousness of the participants (21). We used a checklist of items to guide the interview which is provided in Supplementary File 1, but the interview was open ended and was guided by the narration of the participants. We transcribed the interviews within 24 hours, enriching them by using notes taken during the interviews.

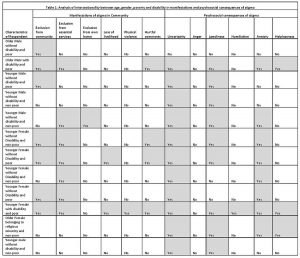

VG did the preliminary analysis by performing open coding of the narratives obtained from the initial eight interviews in Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet. SS then reviewed the codes, and both discussed the coding of the data. After this, we identified the main emerging themes and decided on further sampling to gather information to fill gaps in the emerging understanding of experiences of stigma. We completed four more interviews, achieved data saturation, coded all interviews, grouped themes, and identified the main emerging concepts related to stigma. The coding tree is provided in Supplementary File 2. We then identified representative quotes from the transcripts to support our themes. We also performed an intersectional analysis by representing the key manifestations of stigma and psychosocial consequences in the columns of a matrix and observed the density of the manifestations and consequences among different groups of people with intersecting social determinants namely age, gender, poverty and disability in the rows. We used this to infer the intersectionality in social determinants of stigma.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the ESIC Medical College and PGIMSR with IEC No. IEC/2020/1/13 on May 8, 2020. The interviews were conducted between May and July 2020.

Results

Stigma was perceived as a social evil which violates the human rights of people. Stigmatisation of persons with Covid-19 led to loss of trust in humanity. Covid-19 as a disease leads to much physical suffering and loss of life, but the stigma associated with it was perceived to be worse than the disease itself. The stigma was characterised as “inhuman”, “unacceptable”, and a “violation of rights” by the participants.

Manifestations of stigma against persons with Covid-19Stigma in the community

Stigma manifested itself in the community as exclusion from public spaces, exclusion from the neighbourhood, and loss of support from friends and neighbours. Neighbours who were previously helpful, stopped providing any form of support once the diagnosis of Covid-19 was made. A participant admitted into the isolation ward said,

- Previously when my wife was hospitalised, our neighbours were immensely helpful. They came and visited us in the hospital and took care of our food. This time they avoided us completely after knowing that I am Covid-19 positive.

This experience of exclusion was prominent among people who lived in over-crowded resource-poor neighbourhoods. People who lived in the more well-off parts of the city, and people who lived in apartment complexes did not express this kind of exclusion from neighbourhood and public spaces.

In one case, the family of the patient who recovered from Covid-19 stigmatised and excluded their own family member. A participant said,

- Do you know that the society will not accept people with coronavirus? My own wife will not allow me to come inside my home now. She is telling me that I will infect her and our sons. She is asking me to stay away from my own home. All this is because of you (health system doing testing and treating activities).

Patients who recovered from Covid-19 experienced exclusion from the essential services due to stigma. They described being barred from eating in public dining spaces such as hostel canteen, bathing in public bathrooms in hostels, entering a shop to buy groceries, and collecting water from the public tap. Such exclusion from daily necessities caused severe hardship to all these persons. A resident intern said,

- The other major problem is when I go to the mess (common dining room) to have my food. When I enter and sit at the dining table, all the girls sitting nearby get up and move away. They are not even subtle. They are obvious.

Simple activities which were quite easy to organise earlier became cumbersome after the diagnosis for people with Covid-19. This difficulty was a serious manifestation of stigma. One of the participants said,

- I have diabetes and high blood pressure. Now how will I eat proper diabetic and low-salt food if I am sent out of my own house? How will I manage my life?

Some of the persons interviewed mentioned that they were excluded from their workspaces and lost their livelihood. Loss of job and livelihood is a serious consequence of stigma associated with Covid-19 and could have implications far worse than the disease itself. A participant said,

- I was at work when the call came. My phone is very loud and so all the people working by my side could hear everything that the official said on the phone. So when they heard that I have coronavirus, they all got shocked and, just like that, dropped all the clothes they were holding and moved out of the room. When I finished the call and looked up, there was nobody else in the room.

She lost her job and her source of livelihood after the diagnosis due to the stigma. Another participant reported physical violence due to stigma:

- One of the rogues in my colony took a stone and threw it at me. It hit my forehead and I fainted. When I fainted, they lifted me and took me away to the hospital.

Stigmatisation was not only present in the community, even health facilities stigmatised the patients. Patients reported that they were neglected and ignored by many healthcare providers in the hospitals. They expressed this kind of stigmatisation starting right from the person at the reception desk up to the doctor providing care for them in the isolation ward. A participant said,

- After the nurses started suspecting that I have Covid-19, they stopped coming near me. They stopped checking my temperature and BP. They even stopped giving me tablets and medicines. They kept the medicines and tablets on the table and my daughter had to go and pick it up. Till that time, I was happy with the treatment in the hospital, but after they started avoiding me, I got very angry and upset.

One of the participants narrated,

- For the first two days after we were admitted, nobody came to check us or examine us. We were contacted by phone and they asked us to check our own pulse, BP, oxygen saturation and text it to the doctors. Along with us there were two housekeeping staff and a staff nurse and her husband. We were asked to examine them and monitor them also. Only after two days a doctor came to check on us and draw blood samples. We felt like even our own doctors do not care for us.

Healthcare providers were perceived as being insensitive to the condition of the patients. A participant who recounted the experiences of being stigmatised and discriminated against in the health facility said,,

- Seeing the doctor literally run away from me, my son got angry. He asked the doctor why he was reacting like that. The doctor shouted at my son and said that he should also stay away from me if he wanted to be alive. My son got even more angry.

A participant suffered the serious social consequences of ostracisation by neighbours in his building, because of stigma. He remarked that healthcare providers at health facilities act in a socially insensitive manner. He said,

- This corona test is just another test for you. You think you have to ask a few questions, keep the stethoscope here and there and check us and then order the test. With that your job is over. But do you know how much we have to suffer because of the results of the test?

The interviews revealed several individual and health system level factors that aggravated the stigma. The single largest contributor to stigma was fear of transmission of the virus. The fear of transmission to themselves as well as their families led people to exclude and discriminate against those with the infection. There were reports of people dying in large numbers due to Covid-19. This added to the fear. Lack of awareness about the disease and irrational beliefs aggravated the fear and this in turn worsened the stigma. These irrational beliefs did not even spare healthcare providers. A participant experienced stigmatisation among her colleagues. She said,

- The day I returned to duty after my 14 days of isolation was the worst (day). The staff nurses asked me to go away. They said that they all have young children at home and I am a hazard to them.

Implementation of public health legislation and forced isolation of patients diagnosed with Covid-19, though done with the intention of containing the disease, was reported to be the major aggravating factor behind stigma. It compromised the autonomy of the individual. A participant ready to be discharged from the isolation ward broke down in tears and said,

- Then the health officers came to my house in an ambulance and they forced me to get into the ambulance. I kept saying, “I am ok, I am ok” and kept crying. Everyone was watching me…

The police was involved in identification, contact tracing and isolation of patients with Covid-19 in Chennai, India. The involvement of police worsened the stigma as it made people associate Covid-19 with crime. A participant recollected that the worst part of the stigma was involvement of the police in admitting her to the hospital. She said,

- The sub inspector of police from the nearby police station came to my home. As soon as he came, all my neighbours gathered around my house. The police forced me to go to the hospital. That was the worst part of the whole experience.

Public health professionals who were interacting with patients in the field were rude to many of the patients and this was perceived as another reason for worsening of the stigma. A participant recollected the rude behaviour of the frontline health worker,

- I felt extremely scared. I started crying when I got the phone call from the corporation officer. He was very rude. He kept asking me about my contacts. He kept calling again and again to check if I have gone to the hospital. Every time my phone rang, I was worried, and I was

Concealment of information and lack of transparency in the pandemic-related communication by the authorities created fear and the fear aggravated the stigma. One of the patients, who was just discharged from the isolation ward said,

- …they did not even tell me about the diagnosis. I understood it myself that I must have tested positive for Covid-19. My son and daughter in law were not asked to come to the hospital. They must have tested negative.

He felt that this inadequate provision of information created room for rumours and fear among his neighbours thus worsening the stigma.

The participants perceived unregulated and poor-quality media coverage of the disease as a major reason for worsening of the stigma. A participant said,

- I think the main reason is because of news and media. Everybody is talking about the disease and how it is spreading and killing a lot of people. Everyone is afraid that it will spread to them and they will also die.

Some individuals and communities adopted measures to mitigate the stigma that patients with Covid-19 faced. Some patients understood the disease characteristics, accepted the risk, and isolated themselves. They used this individual level coping style to mitigate the stigma. A participant, completely isolated herself, thus avoiding high levels of stigma. She said,

- Then I thought, being there (in the hostel) I may spread the infection, and people will also feel awkward so better I should go there (to the isolation ward).

In one unique case, a patient explained how solidarity and a sense of community helped mitigate stigma:

- Most of the members of our community work in various capacities in the industrial estate. Our occupation is our linking factor. We are a closely knit community and we all know each other well. We participate in family functions and festivals together. This community link was useful in bringing us together.

Some of the measures adopted by the public health system such as distribution of food and groceries inside containment zones, deployment of volunteers to cater to their needs and to provide physical support to those isolated in their homes were reported as being helpful in overcoming the stigma in the community. A participant said,

- Our entire area was completely sealed off. Outsiders could not enter our area and we could not go out. The corporation officials arranged for vegetables and other provisions to be delivered to us in our street. That way we were together in this difficult time. We supported each other and helped each other.

People also felt that when the number of persons affected by Covid-19 is larger in a particular area, the level of stigma tends to be reduced. A participant explained how their area did not experience much stigma due to Covid-19, because many people were infected and they all became familiar with the illness early on. He said,

- One of the senior members of our community, also a security guard, was the first person to be diagnosed to have Covid-19. After that, his entire family got the infection, then my immediate neighbours got it. We got it after them. So, we all knew about the disease. We stuck by each other.

Advances in mobile-based information and communication technology was perceived as a substantial mitigating factor by providing opportunities to retain lines of communication despite isolation. A participant who was admitted in the isolation ward said that having the ability to communicate through mobile helped her overcome the mental trauma of loneliness and stigma. She said,

- …I also became comfortable because I could talk to my family over the phone.

One interviewee mentioned that if only the public health system trusted people to follow advisories and protected their confidentiality, rather than publicly disclosing their Covid-19 positive status, it would greatly reduce the stigma. A participant, who suffered serious stigmatisation in her community recommended,

- Yes, in future when patients come to your hospital, please do not inform the corporation whether we have coronavirus or not. Please keep the information between us. We will obey all government orders and restrict ourselves in our homes. We will not move outside and infect others. We will also get admitted and follow all orders. We will be responsible. But if you reveal it to the corporation and they come in the ambulance and pick us up and take us away. This is bad because everyone in the neighbourhood knows about our disease. This is the main reason for stigma. If you maintain our information as a secret, all of us can benefit. Please do not inform the corporation

Some participants reported that the efficiency of the public health system reassured them and helped them adhere to instructions issued by the system. This also helped them avoid and overcome stigma. A participant who was very satisfied with the services offered by the hospital and the public health system said,

- …. I went to the hospital where I gave the test (RT-PCR test for COVID-19). The doctor examined me and told me that even though I am Covid-19 positive, as I do not have any symptoms, I can isolate myself at my home. It sounded like a good plan and so I accepted. The doctor gave me a form to sign. I signed it …. everything happened efficiently.

People who experienced stigma due to their Covid-19 positive status reported several psycho-social consequences. The most dominant were the feelings of loneliness, anxiety, anger, humiliation, and helplessness. A participant who was getting ready for discharge from the isolation ward said,

- I am feeling very lonely here in the hospital. I want to go home. I am feeling slightly better that I will be going home today.

Though the wards were full of patients, people experienced loneliness because of the absence of their loved ones who could attend to and take care of them. A patient commented,

- Though the wards were full of patients with fever, cough and cold. I was initially very scared and felt lonely in the ward….

There was general uncertainty and anxiety about possible stigma when people went back to their community. One participant was getting discharged from the isolation ward, but he was worried about the possibility of facing stigma after going back home. He said,

- Today is the fifth day and the doctors have told me that I can be discharged. But I am very disturbed and worried about going home. I am afraid people will isolate me in my community.

Anger was a prominent consequence of stigma. Stigma is an issue of injustice, as there is perceived unfairness and discrimination due to illness. This injustice caused anger among those who were stigmatised. A participant explained,

- My son was so angry, but he could not say anything to them (neighbours who excluded them) He came back and expressed how bad he felt.

In one extreme case of stigma, a participant reported her experience of being humiliated in her community by her landlord. She said,

- I got a phone call from the house owner that she has packed everything that belonged to me and kept it near the garbage bin in the corner of the street. She asked me not to even enter the street. I have to pick up my things from that place and go to a new place to live.

The other prominent psychological expression of the stigma was a feeling of helplessness. A participant reported that,

- The day I got admitted, my wife and children were very scared. My wife was crying inconsolably. She was afraid. The news is full of disease and death. So, she was really afraid. I was unable to help her or comfort her. At that time, I really regretted having myself tested. I was afraid to leave them in the apartment alone where people would really discriminate against them.

The intersectionality of age, gender, poverty, and disability in the experience of stigma due to Covid-19 was analysed through a matrix. The matrix is shown in Table 1. It is seen that the intersection of age, poverty and disability created a higher density of codes highlighting the manifestations and psychosocial consequences of stigma. While exclusion from public spaces and essential services were common across all groups, it is noted that loss of livelihood and physical violence were present only in one case, of a poor woman caring for a child with disability. It is also noted that uncertainty and loneliness were common psychosocial experiences across all groups, but humiliation and helplessness were more among the poor with disabilities. The people disadvantaged by older age, female gender, disability, and poverty were more likely to experience higher levels of stigma than their younger, male, non-poor counterparts without disabilities.

Discussion

This study has documented the lived experiences of social stigma among patients with Covid-19 in the south Indian city of Chennai. Some of the characteristics of the stigma experienced by people with Covid-19 are exclusion from public spaces and essential services and in some cases exclusion from their own homes and families. The people who were stigmatised found it difficult even to obtain essential services like food in a common dining hall, washing facilities in a common bathroom, and shopping at the neighbourhood grocery stores. In case of other stigmatising illnesses like tuberculosis, leprosy, HIV/AIDS and mental illnesses, exclusion has a different dimension. It is manifested usually as exclusion from celebrations and functions, exclusion from marital prospects, and in some cases neglect by the family and friends (22, 23). But social exclusion from basic essentials is a worse form of discrimination and was noted prominently with Covid-19 stigma.

Erving Goffman proposed the theory of stigma in which he described stigma as a “situation of the individual who is disqualified from full social acceptance”. His work on the types of stigma continue to inform the sociological understanding of stigma as a serious determinant of health and healthcare (24). Previous studies of stigma in patients with HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis have demonstrated loss of livelihood due to stigma (25, 26) A similar loss of livelihood was found in this study due to stigma related to Covid-19. The co-existence of stigma and violence among transgendered persons living with HIV in Maharashtra showed that multiple layers of marginalisation and disadvantage such as transgender status, poverty and being HIV-positive worsened the stigma and was associated with violence (27). Since violence is a manifestation of power and stigma is yet another such manifestation, the co-existence of violence and stigma in case of Covid-19 was anticipated and observed.

Loss of social support, neighbourhood support and in extreme cases, even the support of their own family were identified as manifestations of stigma in this study. Covid-19, by virtue of being easily and widely transmitted through droplets and surfaces created a deeper fear of transmission compared to other stigmatising diseases such as tuberculosis, leprosy and HIV/AIDS, which had less vigorous transmission. Therefore, the extent of stigmatisation was more intense compared to these other illnesses.

One other unique characteristic of the stigmatisation associated with Covid-19 was that healthcare providers and hospital staff also discriminated against people diagnosed with Covid-19. This is probably because of the high rates of infection and mortality among healthcare providers during the pandemic (28). There have been reports of doctors refusing admission and treatment of patients with Covid-19 due to risk of infection (29, 30, 31). Similar stigmatisation of patients with HIV by healthcare providers has been reported (32). The stigmatisation was manifested as “differential treatment”, and “refusal to treat”. Patients were not only denied treatment for Covid-19, but also for other common illnesses due to fear of Covid-19. In addition, the patients also perceived healthcare providers as being rude and insensitive. Disrespectful behaviour by healthcare providers not only blocks channels of communication between them and the patients, it also impacts clinical outcomes (33).

Social stigma has been reported to be associated with mental health consequences. The stigmatised persons experience anger, depression, and adoption of adverse health behaviours such as smoking and alcohol (34). Such psycho-social stress related to stigma was also reported in the present study. It was reported as loneliness, anxiety, uncertainty, and helplessness.

One of the major aggravating factors for stigma associated with Covid-19 was the mandatory public health interventions such as display of stickers and application of tin sheets as barricades outside houses of people with Covid-19 and forced admission to isolation facilities. Such mandatory interventions compromised the autonomy and liberty of individuals. Though they may be justified during public health emergencies for the sake of the common good, they were seen to worsen the perception of stigma. The segregation of infected people and families legitimised the stigma (4, 10). The words “isolation”, “quarantine” became household terms and the frequent use of these words in public health communication gave legitimacy to social segregation of people, thus increasing the burden of stigma on the infected.

The use of the police in enforcing the lockdown to achieve physical distancing of people to control the pandemic and for contact tracing and identification of the infected also resulted in aggravation of the stigma associated with Covid-19 (35). Involvement of the police is associated with compulsion and force. People also associate involvement of police with some wrong act and this comes with its own baggage of stigma. The appearance of police officers at their doorsteps created fear and aggravated the stigma that they experienced (36).

This study also sought to connect the social determinants of stigma and the intersectionality between age, gender, poverty, and disability in worsening the stigma faced by persons with Covid-19. Stigma has four components:

- • Identification and labelling of differences happens first, during which people with the particular adverse attribute are identified, in this case Covid-19 disease

- • Then “stereotyping” takes place, which includes associating some adverse social or cultural attribute with the identified condition. For example, when many individuals who attended a social gathering of a particular religious group in India developed Covid-19, the members with the religious affiliation was stereotyped as “super spreaders” of Covid-19 (37).

- • The process of ‘othering’ or differentiation of people with the attribute “them”, very different from “us”, happens and this strengthens the justification for exclusion of the stigmatised.

- • Finally, discrimination and loss of status takes place which disempowers people (5).

This theory of stigma proposes that a power imbalance is essential for stigma to act. This was demonstrated clearly in our study. The poor woman, single parent of a child with developmental disability had a more severe experience of stigma compared to the non-poor man without disability. The power differential that exacerbated the stigma was caused by the presence of intersectionality between age, gender, poverty, and disability. The intersectionality between the disease and race, gender, sexuality, disability has been studied as a factor perpetuating stigma in various illnesses such as HIV/AIDS, mental illness and physical disability (38). The understanding of this intersectionality in factors aggravating stigma has important clinical and public health implications. The most vulnerable sections of the society are also likely to be those most affected by stigma. Therefore stigma reduction and awareness generation interventions must focus on improving the life of the most vulnerable.

This study is a systematic attempt at documenting the lived experiences of stigma among persons who were diagnosed with Covid-19. The strength of the study is the diversity of the sampling and attempt at achieving theoretical saturation to capture the dimension of intersectionality in aggravating stigma. The deep immersion of the researchers in providing Covid-19 care in isolation facilities is both a strength and a limitation. It is a strength because the researchers had an insider perspective to the experience of stigma in the health facility. It is a limitation because it is possible that some of the patients were inhibited by the fact that the interviewers were healthcare providers themselves, though they were not directly involved in their care in the isolation facilities.

The findings of this study help in understanding one of the social consequences of the pandemic, namely stigma. Though the World Health Organization and governments are taking action to increase awareness and reduce the stigma associated with Covid-19, stigma continues to be a major obstacle in achieving effective disease control. All stakeholders must initiate measures to limit stigma associated with the illness, lest the stigma turns out to be worse than the illness itself.

Conclusions

People treated and discharged from isolation facilities for Covid-19 experienced various degrees of social stigma. This was aggravated by social factors including lack of awareness, forced public health interventions and involvement of the police force in public health activities. People experienced various degrees of mental distress because of the social stigma. There is an intersectionality between age, gender, poverty, and disability in worsening the stigma experienced by persons with Covid19. There is a need to immediately address this stressful problem of social stigma associated with Covid-19 to effectively control the pandemic. The lessons learned from this study regarding stigma related to infectious diseases can also help us plan better for future outbreaks and pandemics.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge the guidance provided by Professor Mala Ramanathan, Professor, Achutha Menon Centre for Health Science Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, India, on intersectional analysis of social determinants of stigma.References

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;6736(20):1–10.

- Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020[cited 2029 Dec 15] ;6736(20). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9

- Human Rights Watch. India: COVID-19 Lockdown puts poor at risk:Ensure all have access to food, health care. New York:HRW; 2020 Mar 27[cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/27/india-covid-19-lockdown-puts-poor-risk

- Krishnatray P. COVID-19 is leading to a new wave of social stigma. Wire. 2020 May 12[cited 2020 Dec 15]; Available from: https://thewire.in/society/covid-19-social-stigma

- Link B, Phelan J. Conceptualizing Stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–85.

- Baral SC, Karki DK, Newell JN, Smith I, Rieder H, Rouillon A, et al. Causes of stigma and discrimination associated with tuberculosis in Nepal: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2007 Aug 16[cited 2020 Dec 15];7(1):211. Available from: http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-7-211

- Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Friedman SJ, Meyers BS. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(12):1615–20.

- Patil S, Mohanty KK, Joshi B, Bisht D, Rajkamal, Kumar A, et al. Towards elimination of stigma & untouchability: A case for leprosy. Indian J Med Res. 2019 Jan[cited 2020 Dec 15];149(Suppl):S81–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31070183

- Kane JC, Elafros MA, Murray SM, Mitchell EMH, Augustinavicius JL, Causevic S, et al. A scoping review of health-related stigma outcomes for high-burden diseases in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Med. 2019[cited 2020 Dec 15];17(1):17. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1250-8

- Bhattacharya P, Banerjee D, Rao TSS. The “Untold” Side of COVID-19: Social Stigma and Its Consequences in India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020 Jul 14[cited 2020 Dec 15];0253717620935578. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0253717620935578

- Misra S, Le PD, Goldmann E, Yang LH. Psychological impact of anti-Asian stigma due to the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for research, practice, and policy responses. Psychol Trauma. 2020 Jun 11; 12(5): 461-4.

- Wangchuk RN. Stop Calling People From the Northeast ‘Coronavirus’. It’s Unacceptable. Better India. 2020 Mar 18[cited 2020 Dec 16]; Available from: https://www.thebetterindia.com/220430/india-coronavirus-covid19-delhi-northeast-racism-unacceptable-opinion-nor41/

- Trivedi S. Coronavirus: The story of India’s largest COVID-19 cluster. Hindu. 2020 Apr 11[cited 2020 Dec 15]; Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/coronavirus-nizamuddin-tablighi-jamaat-markaz-the-story-of-indias-largest-covid-19-cluster/article31313698.ece

- Zaman R. Nurses face stigma in Covid-19 fight. Telegraph Online. 2020 May 12[cited 2020 Dec 15]; Available from: https://www.telegraphindia.com/north-east/coronavirus-outbreak-nurses-face-stigma-in-covid-19-fight-in-assam/cid/1772460

- Jane S, Omjaswin M. Chennai neurologist denied dignified burial as mob vandalises ambulance, injures staff. New Indian Express. 2020 Apr 20[cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/chennai/2020/apr/20/covid-19-chennai-neurologist-denied-dignified-burial-as-mob-vandalises-ambulance-injures-staff-2132770.html

- TNN. Recovered coronavirus patients face social stigma in Bihar. Times of India. 2020 Apr 10[cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/patna/recovered-corona-patients-face-social-stigma-in-state/articleshow/75071886.cms

- Sahoo S, Mehra A, Suri V, Malhotra P, Yaddanapudi LN, Dutt Puri G, et al. Lived experiences of the corona survivors (patients admitted in COVID wards): A narrative real-life documented summaries of internalized guilt, shame, stigma, anger. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Oct;53:102187.

- Schmidt T, Cloete A, Davids A, Makola L, Zondi N, Jantjies M. Myths, misconceptions, othering and stigmatizing responses to Covid-19 in South Africa: A rapid qualitative assessment. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0244420.

- Singh R, Subedi M. COVID-19 and stigma: Social discrimination towards frontline healthcare providers and COVID-19 recovered patients in Nepal. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Oct;53:102222.

- Dar SA, Khurshid SQ, Wani ZA, Khanam A, Haq I, Shah NN, et al. Stigma in coronavirus disease-19 survivors in Kashmir, India: A cross-sectional exploratory study. PLoS One. 2020 Nov 30[cited 2020 Dec 20];15(11):e0240152. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240152

- Drabble L, Trocki KF, Salcedo B, Walker PC, Korcha RA. Conducting qualitative interviews by telephone: Lessons learned from a study of alcohol use among sexual minority and heterosexual women. Qual Soc Work. 2016 Jan;15(1):118–33. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26811696

- Mukerji R, Turan JM. Exploring manifestations of TB-related stigma experienced by women in Kolkata, India. Ann Glob Health. 2018 Nov 5;84(4):727–35. doi: 10.9204/aogh.2383.

- Loganathan S, Murthy SR. Experiences of stigma and discrimination endured by people suffering from schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry 2008 Jan;50(1):39–46. Available from: doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.39758.

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2009.

- Chidrawi HC, Greeff M, Temane QM, Doak CM. HIV stigma experiences and stigmatisation before and after an intervention. Health SA Gesondheid 2016 Dec[cited 2020 Dec 15];21:196–205. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1025984815000356

- Courtwright A, Turner AN. Tuberculosis and stigmatization: pathways and interventions. Public Health Rep. 2010]cited 2020 Dec 15];125 Suppl(Suppl 4):34–42. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20626191

- Ganju D, Saggurti N. Stigma, violence and HIV vulnerability among transgender persons in sex work in Maharashtra, India. Cult Health Sex 2017/01/30. 2017 Aug[cited 2020 Dec 15];19(8):903–17. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13691058.2016.1271141

- Lai X, Wang M, Qin C, Tan L, Ran L, Chen D, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-2019) infection among health care workers and implications for prevention measures in a tertiary hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Netw Open 2020 May 21[cited 2020 Dec 15];3(5):e209666–e209666. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9666

- Ahmad M. COVID-19 patient delivers baby in hospital corridor after doctors “refuse” to treat her. Wire 2020 Jun 8[cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: https://thewire.in/health/kashmir-covid-19-pregnant-woman-refused-treatment

- DNHS, Kolar. Jalappa hospital refuses to treat COVID-19 patients. Deccan Herald. 2020 May 16]cited 2020 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.deccanherald.com/state/kolar-chikkaballapur-tumakuru/jalappa-hospital-refuses-to-treat-covid-19-patients-838446.html

- Yamunan S. Fear of Covid-19 spread makes private hospitals turn away patients – or charge them higher bills. Scroll. 2020 Apr 23[cited 2020 Dec 16] Available from: https://scroll.in/article/959727/fear-of-covid-19-spread-makes-private-hospitals-turn-away-patients-or-charge-them-higher-bills

- Dong X, Yang J, Peng L, Pang M, Zhang J, Zhang Z, et al. HIV-related stigma and discrimination amongst healthcare providers in Guangzhou, China. BMC Public Health. 2018 Jun 15;18(1):738. Available from: doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5654-8.

- Grissinger M. Disrespectful behavior in health care: Its impact, why it arises and persists, and how to address it-Part 2. P&T. 2017 Feb[cited 2020 Dec 15];42(2):74–7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5265230/

- Frost DM. Social stigma and its consequences for the socially stigmatized. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2011 Nov;5(11):824–39. Doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00394.x

- Mangla A, Kapoor V. How policing works in India in Covid-19 times. Hindu Business Line. 2020 Jun 2[cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/columns/how-policing-works-in-india-in-covid-19-times/article31729922.ece#

- Satish D. Social stigma, fear of police, onus on god: Why cops are facing a tough time tracing suspected Covid-19 patients. News 18. 2020 Apr 2[cited 2020 Dec 15]; Available from: https://www.news18.com/news/india/social-stigma-fear-of-police-onus-on-god-why-cops-are-finding-it-difficult-to-trace-suspected-covid-19-patients-2561469.html

- Associated Press. As Muslims face stigma and blame for surge in infections, India’s coronavirus fight weakens. News 18. 2020 Apr 25[cited 2020 Dec 15]; Available from: https://www.news18.com/news/india/as-muslims-face-stigma-and-blame-for-surge-in-infections-indias-coronavirus-fight-weakens-2592251.html

- Jackson-Best F, Edwards N. Stigma and intersectionality: a systematic review of systematic reviews across HIV/AIDS, mental illness, and physical disability. BMC Public Health. 2018 Jul 27[cited 2020 Dec 15];18(1):919. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-018-5861-3