ARTICLES

The big Cs of the informed consent form: compliance and comprehension

Shankar V Kundapura, Thirtha Poovaiah, Ravindra B Ghooi

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2013.071

Abstract

The informed consent process is a shield which protects subjects from harms that may be caused by a scientific enquiry. Only a competent participant with a complete understanding of the trial can give informed consent. Although the content of a valid informed consent form (ICF) has been established, the Drugs and Cosmetics (First Amendment) Rules, 2013 have stipulated that ICFs must fulfil the requirements of Appendix V of Schedule Y. We considered 50 ICFs and analysed whether they complied with Appendix V. Our analysis reveals a gloomy picture, with 70% of the ICFs deviating from the requirements of the law. We have identified the elements most commonly overlooked in the ICFs analysed. We recommend certain points which must be incorporated into ICFs to help participants better understand the trial. Our findings indicate that adequate action needs to be taken to ensure the protection of the rights of research participants.

Introduction

The informed consent process is the practical application of the principle of autonomy (1). Informed consent that is given freely is central to ethically sound research. This practical application of autonomy ensures that in no instance are there elements of coercion, deceit or abuse. Informed consent must be obtained in the right manner from participants in research and patients in clinical care (2).

Informed consent is essential for upholding the patient’s autonomy, safeguarding individual rights and promoting ethical research. It aims at helping potential participants who have been deemed suitable for recruitment in a particular study to reach a decision on whether or not to participate. Obtaining informed consent is not a one-time procedure limited to the time of the recruitment of the participant. The process must be a continuous one that lasts till the end of the study. The three cornerstones of an ethical and valid informed consent process are:

- effective communication,

- full information, and

- freely given consent (3).

For the informed consent process to be completely effective in protecting the patient’s rights, the patient must take a decision based on complete comprehension and voluntariness.

The concept of making informed consent in research and clinical practice mandatory is based on the principle of “respect for the patient”. However, there are several challenges that impede the smooth implementation of obtaining effective informed consent. One of the obstacles has its roots in the phrase itself – the first component, ‘information’, comes from the principal investigator, while the other, “consent”, comes from the participant. The patient-doctor relationship is fraught with many problems, including the paternalistic behaviour of doctors, as well as inadequate communication and lack of comprehension (4).

Ambrosius Macrobius once said, “Good laws have their origin in bad morals.” Indeed, a long history of abuse, deceit and lack of moral fibre gave birth to the practice of informed consent. The earliest documented reference to the concept of informed consent dates back to the nineteenth century, and precedes the Nuremberg Code. The Prussian government’s ministry for religious, educational and medical affairs issued a directive which mandated that people could be enrolled in non-therapeutic research only after they had been given an explanation regarding the risks they might face, and after they consented to enrol. The directive also emphasised written documentation and held the medical director responsible for ensuring the ethical conduct of research (5). The first ever documented use of an informed consent form was the one introduced by Major Walter Reed (of the US army) during his experiments on the transmission of yellow fever. He went to great lengths to ensure that the subjects were fully aware of the risks involved, even translating the consent documents into Spanish for the benefit of Cuban volunteers (6).

Although the concept of informed consent became more structured in the Nuremberg Code (7), it was never universally accepted and instances of unethical research mushroomed. Stringent action became necessary to curb this trend. Among the efforts to ensure that research involving human subjects should be ethical was the formulation of guidelines for ICFs in The Declaration of Helsinki (8). These were adopted by the World Medical Association in 1964. The declaration provides guidelines to formulate an informed consent document and conduct the informed consent process.

Informed consent is deemed necessary for most types of experimentation on humans, but may not be so in the case of some experiments. Experiments on humans in the field of behavioural studies might not require the informed consent of the participants; on the contrary, providing information for consent might defeat the purpose of the investigation. In these trials, the participants” interest is best served if they are not given any information about the trial, that is if the trial does not pose any physical or mental risk to the patient. For example, a worker’s response to a fire drill can be best studied if information on the experiment is withheld from the worker. The US Code of Federal Regulations (9) has laid down the following conditions under which the informed consent process can be waived.

- The research involves no more than minimal risk to the subjects.

- The waiver or alteration will not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the subjects.

- It is not practicable to carry out the research without the waiver or alteration.

It is also specified that whenever appropriate, the subjects will be provided with additional relevant information after participation. This process is often referred to as “debriefing.”

In India, Schedule Y of the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules, introduced in 1988, set forth regulatory guidelines for the launch of new drugs. It was amended in January 2005 to bring about harmonisation between the Indian guidelines and the guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). Schedule Y recommended formats for critical documents used in clinical research, one of which is the ICF (10). The mandatory provisions regarding the contents of ICFs are provided in Appendix V of the Schedule. Thus, it is legally binding for the ICFs of trials conducted in India to be in accordance with Appendix V. The Drugs and Cosmetics (First Amendment) Rules, 2013, in sub-paragraph 3(ii) under the section on Responsibilities of the Investigator(s), specify: “The investigator will provide information to the clinical trial subject through the informed consent process as provided in the Appendix V about the essential elements of the clinical trial and the subject’s right to claim compensation in case of trial-related injury or death.” Thus, the law requires every ICF to contain the elements of Appendix V.

In this article, we have attempted to check whether the format of a sample of ICFs is in agreement with Appendix V of Schedule Y. This has been accomplished by investigating whether the contents of the selected ICFs contain all the mandatory elements specified in the Schedule Y. Schedule Y requires each ICF to incorporate 19 essential elements in their entirety. We have compared the contents of the ICFs with the mandatory elements quite strictly.

Materials and methods

We collected 50 ICFs which were used for trials conducted between 2008 and 2013. These ICFs were collected from a site for clinical trials that was located in a tertiary care centre in Pune. The ICFs were the 50 most recent and consecutive ICFs approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). All the 50 ICFs considered were for drug trials and only the English versions were analysed for the study. Due permission was obtained from the hospital authorities and the IRB to analyse the ICFs. An attempt was made to check whether the contents of the ICFs were in accordance with the 19 mandatory elements specified under Schedule Y (11). These elements are as follows:

- Statement that the study involves research and an explanation of the purpose of the research

- Expected duration of the subject’s participation

- Description of the procedures to be followed, including all invasive procedures

- Description of any reasonable foreseeable risks or discomforts to the subject

- Description of any benefits to the subject or others reasonably expected from the research. If no benefit is expected, the subject should be made aware of this

- Disclosure of specific appropriate, alternative procedures or therapies available to the subject

- Statement describing the extent to which confidentiality of the records identifying the subject will be maintained and who will have access to the subject’s medical records

- Trial treatment schedule(s) and the probability for [sic] random assignment to each treatment (for randomized trials)

- Compensation and/or treatment(s) available to the subject in the event of a trial-related injury

- An explanation about who to contact for trial-related queries, rights of subjects and in the event of any injury

- The anticipated prorated payment, if any, to the subject for participating in the trial

- Subject’s responsibilities on participation in the trial

- Statement that participation is voluntary, that the subject can withdraw from the study at any time and that refusal to participate will not involve any penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled

- Statement of foreseeable circumstances under which the subject’s participation may be terminated by the investigator without the subject’s consent

- Additional costs to the subject that may result from participation in the study

- The consequences of a subject’s decision to withdraw from the research and the procedures for orderly termination of participation by subject

- Statement that the subject will be notified in a timely manner if significant new findings develop during the course of the research which may affect the subject’s willingness to continue participation will be provided

- A statement that the particular treatment or procedure may involve risks to the subject (or to the embryo or foetus, if the subject is or may become pregnant), which are currently unforeseeable.

- Approximate number of subjects enrolled in the study.

We examined the ICFs not only for their content and the presence and completeness of these mandatory elements, but also for the language, writing style and presentation of information. We identified certain key words in statements related to the mandatory elements. When these key words/ phrases were absent, the elements were considered to be “present but incomplete.” Certain elements had been omitted altogether from the ICFs. In this case, the elements were regarded as “not present.” Only an element which was present and complete with the key words/phrases was regarded as “present in its entirety.” Let us take the example of the element: “Statement that participation is voluntary, that the subject can withdraw from the study at any time and that refusal to participate will not involve any penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled.” If the word “voluntary” or the phrase “penalty or loss of benefits” is missing, we have termed it “present but incomplete.” All the elements in the ICFs were grouped under the three categories mentioned above. Each instance of an element was recorded as a ‘count’. It was recorded if it was missing but required, as well as if it was present but not required.

Results and discussion

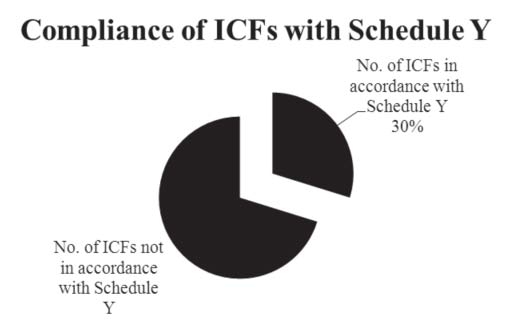

Of the 50 ICFs analysed, only 30% adhered to the norms specified in Appendix V of Schedule Y on the content to be included in an ICF (Figure 1).

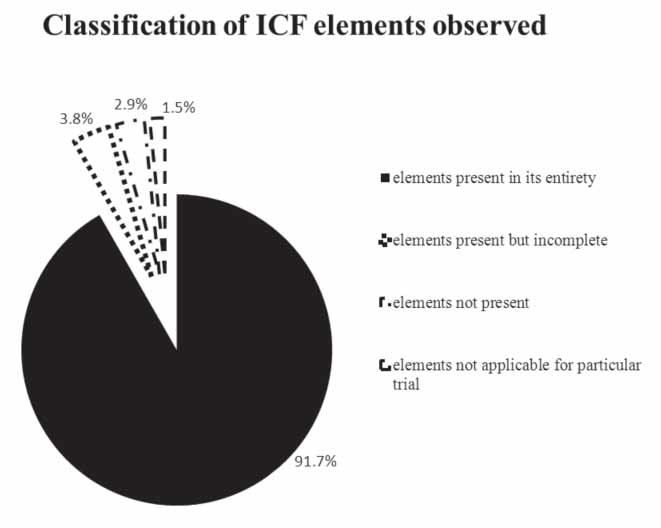

We identified a total of 950 counts of mandatory elements in the 50 ICFs analysed by us. Out of these, 873 counts were present in their entirety, in 63 counts; the element was either absent or incomplete. Among these 63, 37 were “present but incomplete” and 26 were “not present” (Figure 2). In 14 counts, the element was not applicable to the particular trial. Seventy per cent of the ICFs were found not to be in accordance with Schedule Y. These had collectively 63 absent or incomplete mandatory elements with a mean of 1.8 counts of incomplete and/or absent mandatory elements per ICF.

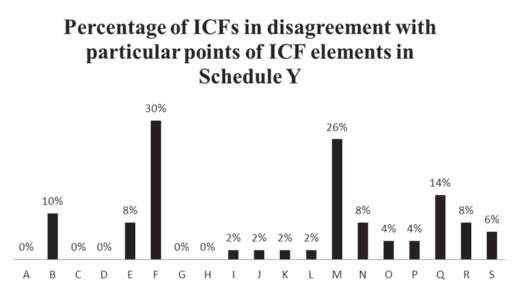

About 30% of the ICFs analysed lacked information on the alternative therapies available to the patient, besides the investigational product. The percentage of ICFs which had not followed this particular norm either said “alternative therapies are available” or contained no statement on the matter at all; there was no disclosure of information on the alternative therapies available to the participant. This implies that the options provided by the ICFs regarding treatment were biased towards the product being investigated. Although it must be noted that the ICFs asked the patients to discuss alternative treatments with their study doctor, Schedule Y clearly mentions the need to “disclose specific appropriate alternative procedures or therapies available to the subject.”

About 26% of the ICFs analysed did not contain a “statement that participation is voluntary, the subject can withdraw from the study at any time and that refusal to participate will not involve any penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled.” ICFs which did not contain key words/phrases such as “voluntary” and “will not involve any penalty or loss of benefits” were deemed to have incomplete or partial information on the said mandatory element. This is an important statement which emphasises the participant’s freedom of expression and action. It ensures that the participants cannot be coerced or blackmailed into participating and continuing to participate in the trial against their will. The participants are free to decide whether they want to participate or continue participating in the trial without fearing any repercussions.

Of the ICFs analysed, 14% did not contain a “statement that the subject—- will be notified in a timely manner if significant new findings develop during the course of the research which may affect the subject’s willingness to continue participation.” In the course of a research study, there are often instances when new information is made available to the investigator from other investigational sites. This information must be passed down to the research participant by the site investigator to keep the process of informed consent active. The new information might affect the individual’s decision to continue participation in the trial. Thus, such information must be given to the participants in a timely manner. The absence of this element increases the burden of risk on participants and keeps them in the dark about the potential peril that may await them.

Around 10% of the ICFs analysed lacked information on the expected duration of the patient’s participation. If the ICF does not furnish information on the approximate time for which the participant is to be involved in the trial, there is a possibility that the participant will face exploitation due to the whims of the study doctor or the sponsor. A patient might end up participating in the trial for much longer than required and the repercussions may be similar to those in the Tuskegee trial (12).

Around 8% of the ICFs analysed did not contain the following.

- Description of any benefits to the subject or others reasonably expected from research. This information gives a clear picture of the therapeutic gain that participation in the trial may bring and assures the participant that he/she is not merely a pawn in a scientific endeavour.

- Statement of foreseeable circumstances under which the subject’s participation may be terminated by the investigator without the subject’s consent. In cases in which the principal investigator feels that the patient would do better with alternative therapy or the patient’s condition is deteriorating, the principal investigator can terminate the patient’s participation in the trial without the latter’s consent. When the participant does not abide by the instructions of the study staff, the principal investigator may be forced to expel the subject from the trial without the latter’s consent.

- A statement that the particular treatment or procedure may involve risks to the subject (or to the embryo or foetus, if the subject is or may become pregnant), which are currently unforeseeable. This statement categorically specifies that pregnant and lactating women should not expose themselves to the product being investigated as it can have a damaging effect on the foetus. Women who are taking part in the trial and who may get pregnant and men whose partners can get pregnant must practice safe sex to avoid pregnancy. This would safeguard the unborn from the effect of the product under investigation. This statement is aimed at averting a tragedy such as the thalidomide disaster (13).

About 6% of the ICFs analysed did not contain information on the approximate number of subjects enrolled in the study. Specifying the number of patients taking part in the experimental treatment might help to instil confidence in the subjects, as having an idea of the sheer number of participants may be a source of reassurance to them.

Approximately 4% of the ICFs analysed did not contain the following.

- The consequences of participants’ withdrawal from the trial and the procedures for orderly termination of their participation. This must be explained in the ICF so that the participant can withdraw voluntarily, with no fear and reservations regarding medical care, penalties or deterrents. The procedures for orderly termination of the participation must be explained in the interest of the safety of the participant.

- The additional costs to the subject that may result from participation in the study were not mentioned. A mention of any additional costs is particularly important in the case of add-on studies, i.e. when the trial is conducted to check the efficacy and safety of add-on therapy and not the main therapy. Clear instructions stating whether the patient must pay/not pay for the main therapy would avoid any confusion.

A small percentage (around 2%) of the ICFs analysed lacked the following information.

- These ICFs did not contain information on the compensation and/or treatment(s) available to the subject in the event of a trial-related injury. This is a point which is of the utmost importance, particularly in the light of the recent discussions on the compensation given to participants for trial-related injury (14). The grounds on which compensation should be given to the participant must be elucidated clearly. In case of trial-related injury, detailed information on the treatment of the injury should be supplied. If this information is not duly provided, the matter would have to be resolved in a court of law.

- There was no information on the anticipated prorated payment, if any, to the subject for participating in the trial. This section deals with the possibility of the participant being paid to participate in the trial. The provision of incentives to the participant to take part in a trial is a matter of controversy as this might lead to unethical exploitation of the participant.

- These ICFs did not contain an explanation about who to contact for trial-related queries and in the event of an injury, or for an explanation about their rights. In the course of a trial, certain doubts may arise, the participant may want more information or medical help, or may have other grievances which need to be addressed. For these reasons, the contact information of the principal investigator and representative of the ethics committee must be provided to the participants. It is important to offer participants a line of communication so that their grievances can be addressed.

- These forms lacked information on the subject’s responsibility in the trial. This is a vital aspect of trials which reflects that the participants are an integral part of the trial and must help it function smoothly. They can do so by following the directions given in the ICF about their responsibility and the instructions given by the study staff.

However, all the ICFs analysed did contain the following elements.

- A statement that the study involves research and an explanation of the purpose of the research. This statement emphasizes that the proposed therapy is not being practised currently and research must be conducted to prove the proposed therapy’s efficacy. The ICF must contain a brief explanation of the aim of the research.

- Information on the trial’s treatment schedule(s) and the probability of random assignment to each treatment (for randomised trials). This section pertains to when, how and what medications will be administered to the participant during the trial. In the case of randomised trials, information on how each participant would be placed in the treatment arms is to be explained. The failure to explain these matters would leave participants in the dark about what medications to take, as well as when and how to take them.

- A description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts to the subject. This information specifies the possible demerits of the trial that could affect the participant adversely. They must be made aware of these risks before their consent is taken.

- A statement describing the extent to which the confidentiality of records identifying the subject will be maintained and who will have access to the subject’s medical records. This statement ensures that the participants’ identity remains confidential during their participation in the trial. It also clarifies who would have access to this confidential information and the reason for which this access is granted to them.

- A description of the procedures to be followed, including all invasive procedures. This section provides information on all the tests and medical procedures which the participants must endure during the course of the trial. If this information is not provided, they will have no knowledge of the tests that they will be put through and the necessity of the tests. Such a situation may be exploited, to conduct tests and procedures that are not sanctioned, for the sake of medical inquisitiveness.

Our analysis has led us to believe that instituting some changes will increase the transparency of trials and build the patient’s trust in a system that is essentially alien to most. The following suggestions should be considered for inclusion in every ICF. Some of these changes were observed in less than 8% of the ICFs analysed.

- The details of the insurance provider, the total cover and the conditions of claim should be made clear.

- Information should be provided on what to do when the participants miss their medication or visit.

- The participant should be informed whether any offsite services are offered by the site staff.

-

The participants must be given clear information on the

amount of time (hours) they are expected to spend on study

visits every week or month.

When enrolling participants in a trial, the site staff must check whether they have time to spare from their regular schedules for activities related to the study so as to ensure the best possible compliance. Good compliance might increase the likelihood of the drug under study being as efficacious and safe as possible. Thus, if time is an important factor, the participant will find it easier to take a decision on whether or not to participate in the trial if he/she is given information on the amount of time (hours) that might have to be spent per week /month on study-related activities. The provision of this information would lead to better compliance, which would be good both for the study and participants.

- The ICF should contain a statement which makes it clear that participants in the trial can avail of legal assistance and which informs them that signing the ICF is not tantamount to surrendering their legal rights.

- The participant should be provided with information on the regulatory status of the drug under study in other countries.

- There should be a statement reassuring participants that the trial has been approved by the regulatory authority and the IRB/IEC.

- The ICF should contain a statement that the profits accruing from the trial are not intended to be shared with the trial participants.

We believe it is most unfortunate that the participant has no information on the insurance policy taken out on him/ her by the sponsor. There is no information on what the clauses are, the grounds on which the participant would be given compensation, when the participant can claim compensation, and when it is not permissible to seek compensation. These unresolved issues would prove to be a hurdle when seeking compensation for trial-related injuries. We suggest that the participant should be given a copy of the insurance policy (or an abstract) along with the ICF, and be made cognizant of the terms and conditions of the insurance policy before giving consent.

Participants might sometimes forget to take their medications and/or miss a scheduled study visit. In such situations, information on “what is to be done next,” ie when and how to take the next round of medication, could prove to be of vital importance. Missed study visits must be communicated to the study staff immediately and remedial measures taken.

There may be times when the participant, for personal or professional reasons, cannot make the scheduled visit to the study site. It should be made known whether, in such cases, the study site would offer to collect biological material, such as blood, and information, such as knowledge attitude questionnaire, from the participant’s place of choice. These are called offsite services, for which the participant’s consent must be obtained in order to protect his/her privacy.

Although these ideas may seem obvious to the trial staff and those involved in clinical research, such a statement will serve as a useful reminder to the participants of their rights, since they may not be familiar with the functioning of a clinical trial. This statement may give the participants courage to seek legal help if they feel that they have been wronged in any way during the trial. This right is available to them even after signing the ICF.

Information on the status of the drug the world over, including details regarding its presence in the market, efficacy and safety, will help participants assess the benefit of the drug under investigation. Information on whether the drug is available as an over-the-counter drug, only by prescription, or only in hospitals, will help them gain an understanding of the drug.

When lay persons come across an ICF, they are overwhelmed by the quantity of scientific literature and information on the disease itself. An assurance in the form of a statement that the regulatory authorities have examined the trial and certified it as safe for participants is of great help.

If a company has designed any product with the help of the participants’ biological samples and is not willing to share the profits with them, this decision must be stated in the ICF. It should be clarified that there are no profit-sharing models in place for the products developed.

Conclusion

The Drugs and Cosmetics (First Amendment) Rules have made the elements of Appendix V of Schedule Y mandatory for every ICF used in trials in India. We fear that there is a long way to go before ICFs become compliant with the provisions of Appendix V. In our small analysis, a meagre 30% of the total ICFs analysed were in agreement with the norms of Schedule Y. More than three-fourths were not in accordance with the regulatory norms of the country. Among the 63 counts of deviation from the elements mandated in Schedule Y, 37 fell under the category of “incomplete”, which signifies partial information and even the absence of key words/phrases mandated in the statements. About 26 deviations related to the omission of the elements required. In 14 instances, a few of the mandatory elements included were not applicable to the particular trial. For example, a statement that the particular treatment or procedure may involve currently unforeseeable risks to the participant (or to the embryo or foetus, if the participant is or may become pregnant) does not apply in observational trials.

In some ICFs, the information was presented in a disorganised manner. Some were written very eloquently, though it is doubtful how far a person with an average command of English and medicine would be able to grasp the contents of such an ICF. It must be noted that some ICFs met every requirement of the Schedule Y guidelines. However, the language and style of writing would, in our opinion, make it difficult for the average Indian patient to comprehend the information and connect with the trial. We have suggested certain elements which, when incorporated, could help the patient gain a better understanding of the issues involved.

It is worth noting that, even as the ethical and regulatory issues pertaining to clinical trials are being made more stringent, ICFs continue to be incomplete or misinformed. Most of these ICFs belonged to trials conducted between 2008 and 2013. The observations which have been made here reflect trends; an analysis of 50 ICFs may not amount to statistically significant findings. In any case, the analysis presents a grim picture and the matter is worth pursuing further. We would also like to suggest that trials must be approved by the ethics committee only when their ICFs contain all the mandatory elements mentioned in Schedule Y.

References

- Osman H. History and development of the doctrine of informed consent. Int Electron J Health Educ. 2001;4:41-7.

- Gelling L, Bishop V, Fitzgerald M, Johnson M, Kenkre J, Greenhalgh T, Haigh C, Read S, Watson R. Informed consent in healthcare and social care research, RCN guidance for nurses. 2nd ed. London: Royal College of Nursing; 2011.

- Ministry of Education, Special Education (GSE) New Zealand. Informed consent guidelines [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2013 Sep 9]. Available from: http://www.minedu.govt.nz/~/media/MinEdu/Files/EducationSectors/SpecialEducation/FormsGuidelines/InformedConsentGuidelines.pdf

- Wood SY, Freidland BA, McGrory CE. Informed consent: from good intentions to sound practices. Proceeding of the Population Council; 2001; New York: The Population Council Inc.; 2002.

- Vollmann J, Winau R. Informed consent in human experimentation before the Nuremberg Code. BMJ. 1996;313:1445-7.

- Yellowfever.lib.virginia.edu [Internet]. University of Virginia Health Sciences Library, Historical Division. Yellow Fever Commission [cited 2013 Sep 9]. Available from: http://yellowfever.lib.virginia.edu/reed/commission.html

- Trial of War Criminals before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No 10. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office;1949;10(2):181-2.

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects [Internet]. Last revised 2008 Oct [cited 2013 Sep 13]. Helsinki, Finland: WMA General Assembly;1964, Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/17c.pdf

- Code of Federal Regulation. 45 C.F.R 46.116. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html#46.116

- Bhatt A. Evolution of clinical research: A history beyond James Lind. Perspect Clin Res. 2010;1(1):6-10.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Drugs and Cosmetics (II nd Amendment) Rules 2005: Schedule Y, Appendix V. Requirements and guidelines for permission to import and / or manufacture of new drugs for sale or to undertake clinical trials [Internet]. New Delhi: MoHFW; 2005 Jan 20[cited 2013 Sep 9}. Available from: http://dbtbiosafety.nic.in/act/schedule_y.pdf

- Cobb WM. The Tuskegee syphilis study. J Natl Med Assoc. 1973; 65(4): 345-8.

- Lécutier MA. Phocomelia and internal defects due to Thalidomide. Br Med J. 1962 Dec 1; 2(5317): 1447-8.

- Appendix XII, Drugs and Cosmetics (First Amendment) Rules, 2013. The Gazette of India, Part II- Section 3-Sub-section (i) (January 30th, 2013)