COMMENTS

Review of multinational human subjects research: experience from the PHFI-Emory Center of Excellence partnership

Hemalatha Somsekhar, Dorairaj Prabhakaran, Nikhil Tandon, Rebecca Rousselle, Sarah Fisher, Aryeh D Stein

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2012.086

Abstract

Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI), New Delhi, India and Emory University, Atlanta, USA, are lead partners in the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute/UnitedHealth funded Center of Excellence (COE) in Cardio-metabolic Risk Reduction in South Asia which provides a vehicle for the development of collaborative research projects. With funding from the National Institutes of Health/ Fogarty International Center, a project was commenced to ensure seamless, thorough and efficient review of this collaborative research. The primary activities of the project are: 1) fact-finding activities which included conduct of a case study and review of policies and procedures of the involved ethics review committees (ERCs); 2) training workshops for COE ERC members and staff and 3) piloting of parallel review of continuing reviews and amendments. A process of parallel review of collaborative research has now been initiated and projects are now submitted simultaneously to the Emory institutional review board (IRB) and PHFI institutional ethics committee (IEC).

Introduction

A Haitian researcher, Jean Pape, once testified to the complexity of the institutional review board (IRB) process, which he designated as the area where collaborative research is the most difficult:

…for any given project there are multiple IRB clearances. Each IRB meets once a month at different times. Each IRB uses different presentations and consent forms. Each IRB has a different set of rules. Some accept oral consent. Others written consent. Others written consent with witnesses, without witnesses. And depending on who the witnesses are, each IRB responds with different comments that must be addressed, a different time period for approval and, therefore, different time for yearly renewal. (1)

The role of ethics review committees (ERCs) and problems encountered in the review of collaborative research

The critical role of an ERC1 is “to facilitate ethical human subjects research by assuring the rights and welfare of study participants” (2). Ethically-engaged research requires a commitment to universal ethical norms, such as those expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki (3) and the Belmont Report (4), tempered by the recognition that their implementation and the relative weight given to competing ethical principles may vary across cultures. Research funded by the United States of America (USA) government, regardless of the setting where the research takes place, must conform to the ‘Common Rule’ (45 CFR 46) that defines and regulates the scope and review of federally-funded human subjects research (5).

With the increase in inter-institutional and international research collaboration, and the requirement for multi-country, multi-site ERC review, there are increasing chances for variation in the scope and capacity of human subjects protection programmes to adequately protect participants from the risks inherent in their participation in research (6). The practice of multi-site ERC reviews has also been criticised for duplication of effort, wastage of time and resources and inappropriate delays. There is even reason to believe that not only do these duplicate reviews provide relatively few benefits, they may actually reduce the likelihood of the studies conforming to relevant ethical standards (7).The present report provides an example of one approach to resolve this dilemma.

The Center of Excellence network and its ethics review experience

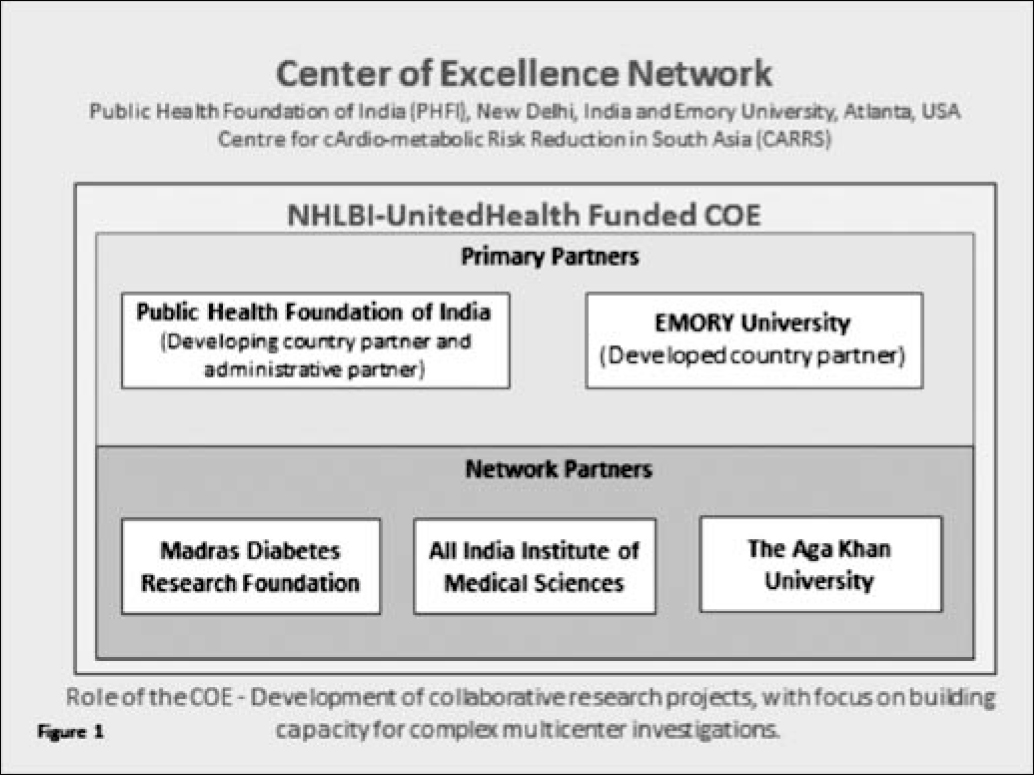

The Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI), New Delhi, India and Emory University, Atlanta, USA are lead partners in the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI)/UnitedHealth funded Center of Excellence (COE) for Cardio-metabolic Risk Reduction in South Asia (CARRS). This COE, one of a network of 11, brings together researchers from PHFI, Emory and has network partners throughout India and Pakistan (Figure1). It provides a vehicle for the development of collaborative research projects, with a focus on building capacity for complex multi-centre investigations. Its activities span a wide range of research modalities, from survey-based research through secondary analysis of clinical data to complex multi-centre intervention trials. All these research projects require efficient ethical review, which unfortunately has not always been the case.

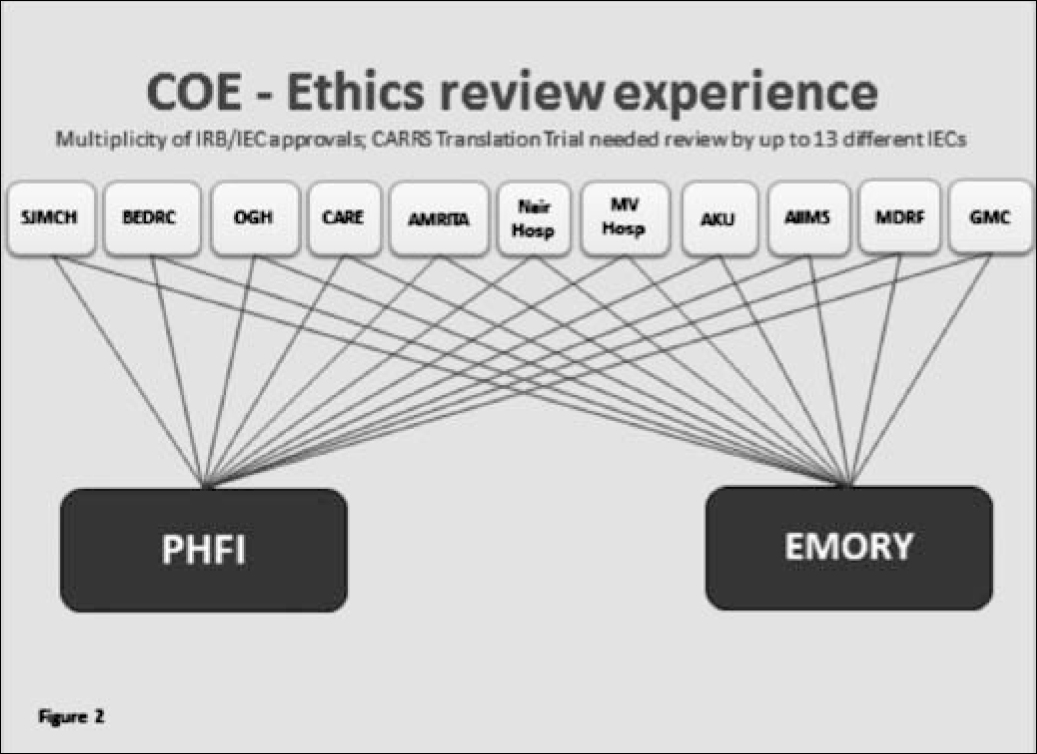

There are numerous challenges to efficient human subject review, especially when multiple ERCs are involved. For example, one of the COE trials required review by up to 13 different ERCs. In addition, nearly 100 investigators/staff needed to be trained in the responsible conduct of human subjects research before the trial could be initiated (Figure 2). The combination of geographical distance; variation in local contexts and cultures; multiplicity of languages in South Asia; differences in ERC format requirements, perceptions of local autonomy and national and international clinical management guidelines; and the complex nature of multi-centre studies with global collaboration have thrown up a plethora of challenges in ethics review. These include delays in the review process, multiplicity of ERC approvals, differences in process and documentation, a need for certification of training in the responsible conduct of human subject research, differences in cultural interpretations, issues of local autonomy, and issues with local and national governments and other approvals. The list is endless.

The project

In order to benefit this complex, multi-institutional federally-funded collaborative research being developed by the COE , a project was undertaken to develop, pilot, and implement a process of thorough, efficient and respectful review of human subjects research in such a setting – in other words, to “facilitate ethical human-subjects research” (1). Funding for this project was provided by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health, USA.

Major project objective and activities

The project aimed to develop a model for the seamless, thorough and efficient review of collaborative human subjects research, and demonstrate its application in practice in a global setting.

The specific aims of the project were: 1) harmonisation of standard operating policies to ensure that US federally-funded research is reviewed according to 45 CFR 46; 2) training of ERC staff and members; 3) parallel review of US federally-funded protocols; and 4) dissemination of results.

The primary activities (described in detail below) included 1) fact-finding activities 2) training workshops for COE ERC members and staff and 3) piloting of parallel review of continuing reviews and amendments.

Fact-finding activities

-

We conducted a case study of the Cardio-metabolic Risk Reduction in South Asia Translation Trial which is one of the studies being conducted by the COE. The Translation trial involves developing and testing integrated multi- factorial cardiovascular disease risk reduction strategies in South Asia .Informal qualitative interviews were conducted with staff who had been involved in the ethics review process for the project. The objective of the interviews was to gather data on project participants’ experiences and interactions with the ethics review process for this study. An attempt was made to incorporate the perspectives of a broad range of representatives from the US and India, including investigators, project coordinators, and ethics review staff. All interviews were conducted face-to-face, with the exception of one phone interview. Data gathered through self-administered structured questionnaires, completed by representatives of each of the six project partner organisations, were used to supplement data gathered through interviews.

Some of the concerns raised by respondents simply reflect the realities of working with multiple partners across multiple countries; some, however, do seem to present opportunities for improvement. Throughout the interviews, the most frequently mentioned challenge was lack of adequate communication between all partners: the developed country partner, developing country partners, and the donor. All interviewees noted an overall lack of awareness among all partners of international regulations and processes. Additional challenges that were mentioned repeatedly throughout the interviews included logistical obstacles; delays due to the need for reviews to proceed in tandem rather than in parallel and for repeated reviews if any institution required changes; all of which resulted in inordinate delays in study implementation timelines.

The case study also compiled suggestions made for improving the multi-centre ERC review process: carrying out exchange visits between partner ERCs; implementing experience-sharing and training exercises; designating a point person from each ERC for direct communication; and issuing conditional approval for the protocols, pending local ERC approval, to avoid the back and forth associated with successive reviews by each partner.

- The second fact-finding exercise took place during a workshop for ERC members and staff of the COE which focused on identifying the major differences between how each partner organisation handles the ethics review for human subjects research. This included a formal review of commonalities and differences in the standard operating policies, such as composition of the ERC; the review processes; experience with US federally-funded research; technical difficulties and other challenges in the review process; measures to ensure ethical conduct of research; and the cost and duration of the review process for each institution.

Numerous themes emerged from the workshop. There were marked differences between the ERC composition in India and Pakistan versus the Emory IRB. Indian and Pakistani ERCs are dominated (and indeed often chaired) by individuals from outside the institution. The ‘member-secretary’ is typically from the institution and provides much-needed continuity. At Emory, almost all members are internal, the IRB chair is an Emory faculty member, and the director is a senior administrator rather than a faculty member or researcher. Indian or Pakistani ERCs do not have a comparable position.

Clearly, all partner institution ERCs are under-resourced for the volume of reviews that they are expected to conduct. Deference is being paid to local guidelines by non-US partner institutions, but training is required for adherence to the letter and spirit of the US regulations when reviewing and conducting US federally-funded research under a federal-wide assurance (FWA).There was a discussion on the advantages of deferral of review to another institution using ERC authorisation agreements but there was consensus that the deferral should not be to an ERC outside the region. The development of more efficient ERC systems among institutions would help streamline subsequent COE projects. It was also strongly felt that direct communication among the ERCs would help minimise misunderstandings about expectations.

Training workshops for COE IEC members and staff

The second major activity of this project involved holding training workshops for COE ERC members/staff. The first human subjects review training workshop was held in May 2011 at Mysore. It invited open discussion about what can be achieved in terms of developing smoother interaction between the COE partners’ respective ERCs, and also included training on human subjects review. The training topics covered “What is research”, “Human subjects” and criteria for ethics committee approval. Compliance with FWAs, the process of institutional deferral via ERC authorisation agreements and individual investigator agreements were also covered in great detail. There was agreement that more opportunities to conduct training of member-secretaries, chairs, and members of ERCs within the COE would be beneficial for the COE partners. The second workshop for COE ERC members was held in November 2011 at New Delhi, with participants from PHFI and the COE network partners. The topics covered were: “What are the ethical issues in human research?”, “Ethical issues in human research in India” and “Best practices for improving the ethics of human research”. The faculty was from Emory University and the All India Institute of Medical Sciences.

Piloting of parallel review of continuing reviews and amendments

The third activity, piloting a parallel review with respect to the collaborative research, specifically of continuing reviews and amendments, was also initiated. As part of this process, all documents pertaining to the review are submitted simultaneously to the Emory IRB and PHFI IEC. Staff members of the respective institutions identify likely concerns, discuss and resolve these prior to member review.

This process facilitates review by the Emory IRB concurrently with the Indian partner(s) and approval being obtained from both at the same time, ‘pending approval by the local ERC of record’.

Other activities include establishment of a COE ERC member-secretary network, which is ongoing, and dissemination plans which include setting up a website and adding workshop materials to the PHFI Global Network website. This would include information on how to set up ERCs, case studies, FWA compliance etc. Other plans include disseminating knowledge to other COE partners and field sites by electronic distribution of materials, and by live and web-based training. Collectively, these activities will enhance communication among partner institutions in global research.

Initiation of parallel ethics review

A communication loop has been established between two point persons at the PHFI and Emory ethics committees for the parallel ethics review. This increases efficiency and the coordination of administrative processes wherever possible, and makes adherence to US regulations easier. The role of the point persons of ERCs in the parallel review is to complete a preliminary screening of the documents to identify any glaring problems, examine the application and documents submitted to make sure they are in order, communicate with each other and submit the documents to the committee. A few issues were raised during the first parallel review. For example, Emory has an online IRB submission whereas PHFI is yet to move to online submissions. Would the COE study be given preference over other submissions? Would the submissions involve having a common form? This is not feasible at present but could be attempted to suit both ERCs.

Additional important observations were made by the researchers and staff during the first parallel review of an amendment to a study protocol. One such observation was with respect to proposal submission: “One finding from this already is that the seamlessness and efficiency needs to start with application preparation.” It is important that “Research teams need to confirm with each other exactly what is being submitted, even reviewing each other’s submissions, before putting them in process.” This would reduce communication lapses due to the geographical distance between the research teams. Another important issue which cropped up was related to the different ERC approval periods with different expiration dates for the same collaborative research project. “Would it make sense to try to synchronise the dates? Or would that in itself be too burdensome?” An important fact to remember is that each ERC is independent and so, with the designation of a point person in each, there is now a smoother review process in place. Despite a few initial hiccups, increased communication between the research teams and the two ERCs has improved the ethics review process overall. With an increasing number of reviews, the process should be streamlined in due course.

Conclusion

This project highlights the numerous challenges in human subjects research review when conducting global health research. Considering the different policies and processes being used by the various ERCs within the COE, enhanced communication is the key to providing efficient and timely review of collaborative human subjects research. Clearly, research timelines often suffer in such large international collaborative multi-centre studies but that can be minimised with improved communication and coordination. Tackling the problem of under-resourced partner ethics committees is also crucial.

It is also important to keep in mind the requirement for adherence to US regulations when non-US organisations conduct US federally-funded research, and also when such research is reviewed.

In addition to improving communication between ERCs, reducing multi-layered, repetitive ERC review by making use of the deferral process is worth advocating. Researchers have argued that the cumbersome multi-ERC system, by creating administrative obstacles, may itself be unethical, as it drives up costs of research and creates unnecessary delays (8, 9).Suggestions for overcoming these obstacles included creating a single ERC application that would be accepted by all sites (10) and giving local ERCs complete control over the informed consent process (8, 9).

The US National Bioethics Advisory Commission has published a number of useful suggestions to tackle these issues, both from researchers who provided testimony, and from respondents to NBAC commissioned surveys (1):

- Seek ways to increase communication among multiple ERCs responsible for review of US sponsored research conducted in other countries, perhaps through an annual meeting of the chairs of the IECs/IRBs from collaborating countries.

- Develop a system of coordination among investigators and local ERCs.

- Seek input from host country ethics review committees or community members in the host country in designing the consent process before review by a US IRB. The US IRB should be flexible and receptive to such proposals.

- Have local investigators design consent forms in the host country, followed by approval by the local ERCs, rather than having the documents and their approval come from the US.

- Include members who have experience of working or living abroad on US IRBs that review protocols for research in other countries.

Once the process of parallel ethics review is fully functional, we expect the review efficiency to be much improved in terms of reduced time for review and approval. Researcher satisfaction will also be obtained at the end of the project.

Besides ensuring the adequate protection of human subjects by all the institutions involved, harmonising of policies and procedures for the highest quality of review enhances and eases this kind of research. This project builds partner institution capacity to conduct reviews of protocols pertaining to human subjects in accordance with the National Institutes of Health requirement, which ensures that the recipients of US federal funding conform to the Common Rule. This model is also generalisable to any other bilateral or multilateral research collaboration.

Acknowledgement:

We thank KM Venkat Narayan, Hubert Department of Global Health Emory University, for his insights.

Note:

1 In the US, ethics review committees are called institutional review boards (IRBs). In India they are more commonly known as institutional ethics committees (IECs). We have referred to them as ethics review committees (ERCs) throughout the text, except for a specific committee where we have used the term that the committee uses for itself, eg the Emory-IRB or the PHFI-IEC.

References

- National Bioethics Advisory Commission. Ethical and policy issues in international research clinical trials in developing countries [Internet]. Bethesda: National Bioethics Advisory Commission, 2001[cited 2012 Sep 28]. Chapter 5. Ensuring the protection of human participants in international clinical trials; 19p. Available from: http://bioethics.georgetown.edu/nbac/clinical/Chap5.html

- Emory University Institutional Review Board [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Emory University IRB; [date unknown] [cited 2012 Sep 28] Available from: http://www.irb.emory.edu./

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects[Internet]. Seoul, Korea: WMA; 2008 [cited 2010 Mar 18]. Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html

- HHS.Gov, US department of health and human services [Internet]. Washington D.C: US department of HHS. The Belmont Report.Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research [Internet].1979 Apr 18 [cited 2012 Sep 28]. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/belmont.html

- HHS.Gov, US department of health and human services [Internet]. Washington D.C: US department of HHS. Code of Federal Regulations Title 45 Public Welfare Part 46: Protection of human subjects [Internet]. 2009 Jan 15[cited 2012 Sep 28]. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html

- Cohen ER, O’Neill JM, Joffres M, Upshur RE, Mills E. Reporting of informed consent, standard of care and post-trial obligations in global randomized intervention trials: a systematic survey of registered trials. Dev World Bioeth. 2009 Aug;9(2):74-80.

- Menikoff J. The paradoxical problem with multiple-IRB review. N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 21;363(17):1591-3.

- Gilman RH, Anderton C, Kosek M, Garcia HH, Evans CA. How many committees does it take to make a project ethical? Lancet.2002Sep 28; 360(9338):1025-6.

- Gilman RH, Garcia HH. Ethics review procedures for research in developing countries: a basic presumption of guilt. CMAJ. 2004 Aug 3;171(3):248-9.

- Pape JW. Institutional review boards: consideration in developing countries. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(3 Suppl): 547.