ARTICLES

Is there an elephant in the room? Boundary violations in the doctor-patient relationship in India

Sunita Simon Kurpad, Tanya Machado, R B Galgali

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2010.029

Abstract

An anonymous postal survey on the awareness of the occurrence of nonsexual and sexual boundary violations (NSBV and SBV) in the doctor-patient relationship in India was conducted with psychiatrists and psychologists working in the state of Karnataka in India (n=51). Though this was not designed to be a prevalence study on violations, the results suggest that both NSBV and SBV do occur and, more importantly, respondents felt that this is an area which needs urgent attention in India. There was disagreement on whether some behaviours in certain situations could be construed as NSBV in the Indian culture. Though several respondents agreed that there was a need to develop guidelines on this issue in India, there was a perception that the problem was not in the availability of guidelines but in their implementation. The ethical implications of the study are discussed.

Introduction

The doctor-patient relationship is central to the healing art of medicine (1). However, the dynamics of authority, power, control and trust in the relationship can make a patient vulnerable to abuse by the treating doctor. Boundaries exist in the doctor-patient relationship to protect the patient from abuse (2). Defining these professional boundaries and what constitutes boundary violations has been extensively discussed in the West (3). In India, boundary issues have been discussed in the context of psychotherapy (4). Nonsexual boundary violations (NSBV) can encompass a range of behaviours from dual relationships with patients and undue self disclosure to accepting gifts for personal use. Sexual boundary violations (SBV) can range from inappropriate touch and sexual talk to sexual intercourse with a patient.

In the West, doctor-patient sexual boundary violations have been described as a “public health problem”. (5) Anecdotal experiences of doctors working in India suggest that sexual abuse and other forms of boundary violations do occur here. However, we could find little in the form of published literature from India on inappropriate behaviour by doctors towards their patients (6). Both NSBV and SBV can have devastating effects on patients; they can have devastating effects on doctors as well, if the allegations are false (7, 9). There can even be negative consequences to the doctors or therapists to whom the BV is reported. We submit that there is an urgent need for discussion in this area in India. The first step would be to learn whether or not these boundary violations occur in India and, if they do, whether doctors are aware of the existence of this problem. “Consensual” acts of SBV with adults are considered unethical but not illegal (3). Nonconsensual acts which amount to sexual harassment and rape are outside the purview of this study.

Methods

An anonymous postal survey on the awareness of the existence of boundary violations by doctors and therapists in India was conducted among psychiatrists and clinical psychologists practising in Karnataka. This study was not designed to specifically measure the prevalence of boundary violations. A questionnaire designed by the authors, a covering letter explaining the purpose of the questionnaire and a self-addressed stamped envelope was posted to 163 individuals. (The list of psychiatrists and clinical psychologists known to be practising in Karnataka was obtained from the mailing list of the Karnataka branch of the Indian Psychiatric Society and the Karnataka Association of Clinical Psychologists, respectively.) The questionnaire covered a range of NSBV like active socialisation with patients, becoming friends with patients, undue self disclosure, accepting gifts for personal use and accepting free services from patients. It also covered a range of SBV like inappropriate/ unnecessary physical examination, inappropriate touching, sexual talk/ jokes, sexual touching and sexual intercourse with patients. The questionnaire also covered some practice-related issues like physical examination without the use of a chaperone. At the beginning of the questionnaire, the respondents were told that the term “mental health professional” in this survey meant psychiatrist, doctor, psychologist, social worker, nurse or counsellor. The study was approved by the institutional ethical review board at St John’s Medical College, Bangalore.

Results

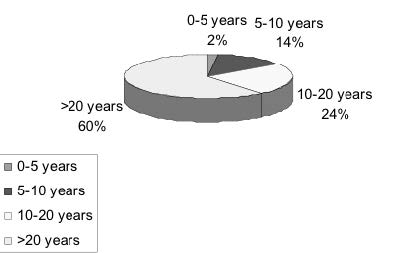

163 questionnaires were posted and 51 replies were obtained (9 female psychologists, 5 male psychologists, 5 female psychiatrists and 32 male psychiatrists). 6 were returned by the postal department as the addressee had moved. The profile of respondents in terms of the number of years after their postgraduate qualification is listed in Figure 1.

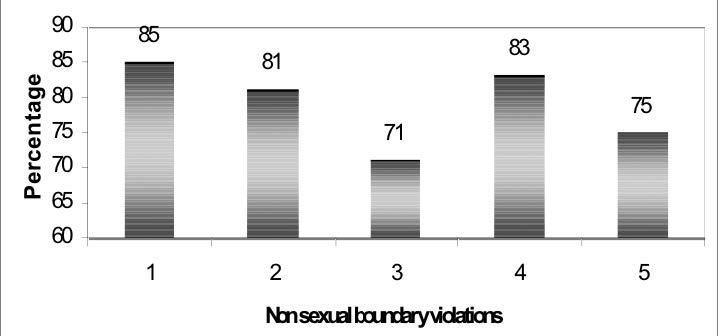

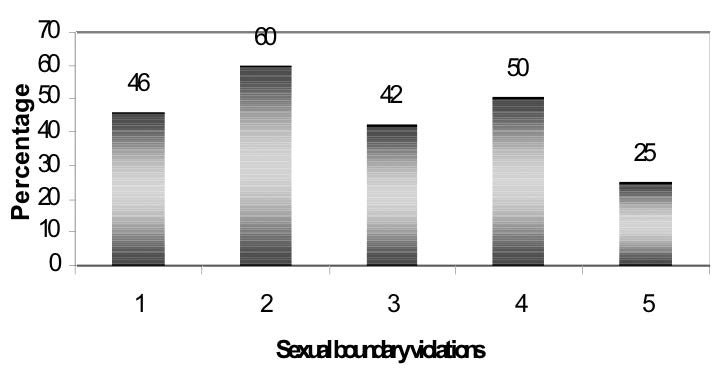

The percentage of respondents who were aware of the occurrence of various kinds of NSBV and SBV is shown in Figures 2 and 3.

- Active socialising with patients

- Becoming friends with patients

- Undue self disclosure to patients

- Accepting gifts for personal use

- Accepting free services from patients

- Inappropriate/ unnecessary physical examination

- Inappropriate touching

- Sexual talk/ jokes with patient

- Sexual touching patient

- Sexual intercourse with patient

| Table1 | |

| Source of information regarding BV | |

| * Source of information | Number of respondents (percentage) |

| Patients | 23 (45) |

| Carers | 17 (33) |

| Colleagues | 30 (59) |

| Case records/ case files | 4 (8) |

* Some respondents cited more than one source

| Table2 | |

| Timing of boundary violation | |

| *Number of years ago | Number of respondents (percentage) |

| <1 | 6 (12) |

| 1-5 | 13 (25) |

| 5-10 | 17 (33) |

| 10-20 | 14 (27) |

| >20 | 9 (18) |

* Some respondents cited more than one source

| Table3 | |

| Number of respondents who felt the some behaviours by doctors/ therapists in certain circumstances DO NOT constitute a BV | |

| Taking gifts for personal use from patients | 15 (29) |

| Becoming friends with patients | 10 (20) |

| Accepting free services from patients | 9 (18) |

| 1-5 | 13 (25) |

| 5-10 | 17 (33) |

| 10-20 | 14 (27) |

| Accepting free services from patients | 9 (18) |

| Actively socialising with patients | 7 (14) |

| Undue disclosing about self to patient | 7 (14) |

| Inappropriate/ unnecessary physical examination | 1 (2) |

| Inappropriately touching patient | 1 (2) |

| Sexual talk/ jokes with patient | 0 |

| Sexual touching patient | 0 |

| Sexual intercourse with patient | 0 |

| Table4 | |

| Awareness of investigations into allegations of SBV | |

| Circumstance | Number of respondents (percentage) |

| Number of respondents who were aware of at least 1 likely false allegation that was investigated | 11 (22) |

| Number of respondents who were aware of at least 1 likely false allegation that was NOT investigated | 15 (29) |

| Number of respondents who were aware of at least 1 likely true allegation that was investigated | 7 (14) |

| Number of respondents who were aware of at least 1 likely true allegation that was NOT investigated | 12 (24) |

Nearly 61% of the respondents had heard of boundary violations by psychiatrists, 45% by other medical doctors, 37% by psychologists, 18% by social workers, 10% by nurses, 22% by other counsellors and 2% by ward boys and OT (quoted exactly as this acronym) personnel. Several had heard of violations by more than one group of health professionals. More than half of the respondents (60%) had heard about a boundary violation by a particular health professional more than once. The source of information regarding BV is listed in Table 1 and the timing of occurrence of BV in Table 2. Many respondents (78%) had heard of physical examination of patients – and 59% had heard of physical examination of children – being done without an attendant, chaperone or guardian being present.

Several respondents stated that in certain circumstances in our culture, certain actions by doctors/ therapists (such as accepting gifts) cannot be construed as boundary violations (Table 3). Some suggested that if a patient insists on the doctor taking a gift, it is not a BV. One said that if the socialisation is initiated by the patient, it is not a BV. One respondent felt that a “long handshake/ hugging in a consoling manner [of patients] with panic disorder is not a BV”. This respondent felt that these actions were actually helpful. The same respondent also felt that “pentothal abreaction would work only if [the] patient and [the] doctor are alone,” and that, in sexually abused patients, “physical examination helps.” On the issue of physical examination without chaperones, some respondents felt that it was often not feasible to arrange a chaperone in India.

About half the respondents (53%) had heard of at least one incident of sexual boundary violation in which it was likely that the allegation was a false allegation and 49% of respondents had heard of at least one incident where it was unlikely that the allegation was false. A third (33%) of respondents had heard of at least one allegation of SBV that was investigated but a larger number (51%) had heard of at least one allegation of SBV that was not investigated. Table 4 lists some details about the investigations.

A substantial number of respondents (41%) felt NSBV were a concern, while about half (49%) felt that SBV were a concern in India. Most respondents felt that the issue was not discussed adequately with various groups. Only 10% felt that the topic was taught to or discussed adequately with students, 22% with colleagues, 8% with patients and with 18% with carers. A large number (88%) felt that there was a need to develop guidelines on the topic of professional-patient boundary issues in India.

Discussion

The study design was aimed at assessing awareness among respondents while retaining their anonymity. It has been reported that studying the area of boundary violations is methodologically difficult and, generally, anonymous surveys have generated useful data (3, 10, 11). We felt an anonymous survey would allow respondents to feel comfortable enough to discuss their experience and opinion on this topic. As our results show, boundary violations are not limited to any one group of health professionals and this is in agreement with evidence from other countries (11, 12). Our data only show the percentage of doctors who are aware of BV by particular groups of health professionals. It should not be assumed that just because more respondents in our survey had heard of BV by psychiatrists, other medical doctors and psychologists, that BV is more common in these groups. It could be that as our respondents were psychiatrists and clinical psychologists, they are more aware of boundary violations within their own group. The finding could also be due to the possibility of several doctors referring to the same incidents. We have used the term “doctor-patient relationship” in a broad sense rather than “mental health professional-patient relationship” in this article.

Though there is a degree of awareness about NSBV and SBV, it is clear that not everyone is aware of its existence in the doctor-patient relationship in India. If treating therapists do not know that this issue exists here, they are unlikely to be adequately equipped to handle it.

The issue of a possible “cultural sanction” with NSBV needs further reflection. Even if it is the patient who insists on presenting gifts for personal use (and even if most doctors have occasionally accepted gifts), it may still be a boundary violation with its attendant problems. The skill to be gently assertive while refusing such gifts without hurting the sentiments of patients and carers usually comes with experience but can be easily taught to junior doctors. Common sense would dictate that accepting a box of sweets by a patient who can afford it, on behalf of the entire treating team and on an occasion, would be acceptable. Self disclosure can be a useful technique to be used by an experienced therapist to help the patient feel better, but undue disclosure about oneself to make the therapist feel better is unacceptable (13). Becoming friends with patients is inadvisable (14).

No single culture defines India. However, if one accepts that a boundary violation is anything that violates the dynamic of the doctor-patient relationship, it would not be difficult to introspect and differentiate between a boundary crossing and a violation (15). Of course, situations may arise in which an occasional gift taking or having a social or business contact becomes inevitable for some reason. A simple “self test” for doctors could be, “Never do something you would not like other colleagues to know about.” The major concern is that NSBV are the well known “slippery slope” to SBV (16). Not all NSBV lead to SBV, but nearly all SBV have started with NSBV (17). Setting limits protects not only patients but also doctors. It is known that behaviourally disturbed patients can also harass doctors (18).

In sexual abuse literature the world over, it is known that false allegations are rare but do occur (9). Unfortunately, by the time the inquiry “clears” the doctor the damage to that doctor’s reputation is already done. Physical examination of patients without a chaperone is an area in which some doctors put themselves at risk. It is inadvisable to lower standards of good and safe practice citing logistic reasons in India. A “comfort touch” can be risky in some situations as it is the meaning of the doctor’s behaviour to the patient and not his/her intention that determines harm (19).

Our questionnaire was designed only to ascertain whether respondents were aware of investigations into allegations of SBV; it did not seek to ascertain why some cases were investigated and some were not. Our data show that awareness of the occurrence of SBV allegations that were not investigated was higher than those which were investigated (especially in the cases where an allegation was likely to be true). However, we cannot presume that allegations that are investigated are more likely to turn out to be false, as it has been noted earlier that false allegations are likely to be over-reported (10).

Is there an elephant in the room?

Our data suggest that both SBV and NSBV do occur in the doctor-patient relationship in India and that it is not a new phenomenon. As there is no published scientific literature in peer reviewed journals on this topic in India, it suggests to us that the idiom about the elephant in the room is an appropriate one (implying that there is an obvious problem that is being ignored).

This elephant is not a cultural or an Indian phenomenon. There is a parallel in the western literature in the natural history of disclosure of sexual abuse. Usually incidents come to light after several years (20). Patients are usually reluctant to report these issues due to concerns about confidentiality, shame, not being believed or even because they are emotionally attached to the doctor. Others may have been victims of past sexual abuse (“the sitting duck syndrome”) and therefore find it even more difficult to disclose the problem (21). Family members might not want to make complaints due to confidentiality and stigma issues. Offending doctors can be reluctant to seek help for behavioural difficulties as they fear adverse publicity. “Third party” doctors (doctors to whom the patients subsequently disclose the history of abuse) might not report the abuse due to concern about causing “further harm” or the perceived suicidal risk to the patient (especially if the patient and their family are unwilling for an inquiry process to take place). Others might not believe the patient, they may not understand the seriousness of the BV if it did not amount to sexual intercourse or they may be unaware of the risk of serial offences by the offending doctor. Their additional concerns may be the consequences to the errant doctor and even to themselves if they are perceived to be “whistleblowers”. Whistleblowing can have serious career consequences (22, 23). Mandatory reporting laws regarding sexual abuse of patients by doctors have received mixed reviews across the world (24). Doctors have felt they would rather consult a senior colleague or counsel the offending colleague themselves when they come of know of professional misconduct (25).

In India additional factors are also relevant. When faced with (nonsexual) medical malpractice, patients and carers are generally disinclined to give formal complaints to local medical councils and courts, as there is an impression that anyway justice will not be served (26). Media reports suggest that in the few cases of sexual abuse which find their way to court, the inquiry process is perceived to be as abusive as the original abuse (27). So, the reason why no one openly talks about doctor-patient abuse is not because it does not occur. Rather, talking about it can lead to adverse consequences to everyone who knows about it. This can lead to a false sense of security in which we feel that doctor-patient abuse is not an issue in India because we do not often hear of it.

Limitations

Our study was an anonymous postal survey, designed to be simple and non time consuming to maximise response rates from busy doctors. This meant we did not go into detail about the actual incidents of NSBV and SBV that the doctors had heard about. However, the comments section gave doctors the opportunity to discuss any point further (Table 5). Our study focused on asking respondents about their awareness of boundary violations being an issue in India, not whether or not they had violated boundaries. If one is studying prevalence of this issue in respondents, then surveys would tend to underreport the phenomenon as some offenders would not wish to report their own behaviour, even anonymously. As our study was not a prevalence survey, the low response rate would not dilute, but arguably add to, the central finding of this study – that both NSBV and SBV occur in the doctor-patient relationship in India, but not everyone is aware of it and this is not often openly discussed from an academic viewpoint. Surveys do have the intrinsic bias of eliciting a higher response from respondents who feel more strongly on an issue, but some respondents in our survey did participate despite stating that they felt it was not an issue in India. Even a single case report on an important clinical issue is a valid method to draw the attention of the medical fraternity to a medical problem. In the case of sexual boundary violations, one is unlikely to be able to get informed consent from the patient to write up the case report. Therefore, an anonymous survey is an important method to study this issue. One can only guess the reasons for non-response – either the non-responders did not receive the questionnaire, or they were too busy, or they did not think BV was an issue, or the topic made them uncomfortable in some way.

Implications

Acknowledging a problem is the first step towards dealing with it. This preliminary study suggests that not only do both NSBV and SBV occur in the doctor-patient relationship in India but not all doctors are aware of it. As the fundamental ethical principle in medicine is primum no nocere (first, do no harm), there can be no doubt that we need to deal with this issue. However, attempting to do so can pose certain ethical dilemmas. First, awareness about BV has to be made universal among doctors, therapists and all health professionals, as our data show that BV is not restricted to psychiatrists and psychologists. Incorporating the topic into the undergraduate and postgraduate medical ethics curriculum would be a good start (8). However, it has to be done without making students wary about the doctor-patient relationship, which remains central to the practice of medicine (1). Second, there is a need to develop clear, culturally acceptable guidelines on boundary issues in India as that can reduce unethical behaviour among doctors and therapists (28 , 29). Given the cultural diversity in India, developing acceptable, nuanced guidelines might be a challenge (30, 31). Third, third party doctors should have clear guidelines on what needs to be done when a BV is alleged, without risking the costs of whistle blowing. Fourth, we need to have a confidential, workable and credible investigating system headed by specially trained individuals so that the inquiry process is not abusive to patients or to errant doctors. On the one hand, patients and carers should not feel intimidated about making complaints but on the other hand, false allegations must be dealt with strictly if made with malicious intent. The “predating” boundary violator has to be handled differently from the “unwell” violator. Last, as it is unrealistic to expect SBV to never occur, future patients have to be protected. Patient and carer education on this topic can be in the context of protecting oneself from sexual abuse in general. It would be crucial to ensure that the information given is not sensationalised and does not lead to further reluctance to gain access to much-needed psychiatric and medical care in India.

We suggest that, at this stage, one does not need a prevalence study on BV (even if it were feasible in India). We now have more than anecdotal evidence that NSBV and SBV do occur in this country. It really does not change things very much whether it is one doctor or 10 who engage in SBV, as sexual abusers can turn out to be serial offenders. The Kerr Haslam Inquiry in the UK details how a single doctor ended up abusing at least 67 patients and another at least 10 patients spanning a period of two decades (20).

There can be little debate that we need to address this issue now. How we should go about doing it, with minimum collateral damage and keeping sensitivity to cultural issues in mind, should be the subject of future research using qualitative research methodology. Till those data become available, it might be wise not to ignore lessons from the West in terms of managing patient victims of SBV and the alleged offenders (5, 21). This article should not imply that abuse is a phenomenon only in the professional-patient relationship. This is only one facet of the problem of sexual abuse in a society. This study implies that psychiatrists and psychologists want to shake themselves out of their collective learned helplessness on this issue. Having clear, nuanced ethical guidelines and the ability to practise them effectively can only strengthen the doctor-patient relationship, which is the fundamental rock on which the healing art and science of medicine is based.

Table 5: Some comments by individual respondents

- Appreciate taking up the issue as awareness on this topic is important and necessary. Need to sensitise other medical personnel too. This is a neglected topic. Worth developing guidelines. Sometimes naive therapists are exploited by patients!

- Maybe less here than in other professions. Personality of offending mental health professional needs to be evaluated. Need to refer for treatment on a case by case basis (if needed). Closing door when patient is alone with doctor should be strictly avoided.

- Non service staff to be included and guidelines given to them too. For example, receptionists, OT attendants after ECT or narco analysis after the psychiatrist leaves (the room).

- Make literate and illiterate patients aware of boundary issues in the context of physical examination. Display ‘Dos and don’ts’ in all major hospitals. Then similar notices can be put in psychiatric hospitals. In case of BVs in the context of therapy, first carer and then patient to be adequately informed. All hospitals should have suggestion box/ complaint box.

- Having guidelines and training are necessary but BV will continue to occur as with (violation of) other ethical guidelines.

- This is an important area. Needs urgent attention. (The issue of boundaries)… is very tough unless therapist has trained himself to be vigilant about his own internal and psychic state. I have not heard of any such reports.

- Therapist should respect the sanctity of the therapist patient relationship. They should not fall prey to momentary pleasures.

- Existing guidelines in any standard textbook is fine if implemented. How to implement them should be the focus rather than reinvent the wheel. Every professional is aware of the risk of crossing boundaries. In spite of knowing, if he crosses boundaries, he will have to face consequences. Boundary violation issue is surely a disgrace to the profession and the fraternity giving enough room for ‘generalizations’ in the minds of the public.

- (In case of an allegation) there should be an investigation by a body comprising a senior psychiatrist and three others. Incident 1- warn if found guilty, incident 2- punish.

- Gift taking and self disclosure an issue. SBV can be a concern in smaller centres. BV usually discussed as gossip and not as a professional issue. There are no clear guidelines as to what one has to do when one notices it (BV).

- From an academic viewpoint it (the study) is appropriate.

- Whilst I think what you are doing is necessary and important the crying need of the hour is public health awareness/ education.

- Thank you for the sensitisation regarding this topic.

- Guidelines are already there. Ethics classes needed. (BV can be due to) mood disorders or manifestations of ‘general loose behaviour’.

- This is an important area. Definitely need guidelines, teaching, monitoring and where needed deterrent action

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the following: Elizabeth Kurian, Postgraduate Student, Department of Psychiatry, St John’s Medical College Hospital, Bangalore, whose clinical skills in a busy outpatient clinic resulted in the preliminary impetus for this study; G D Ravindran, Head of the Department of Medical Ethics, St John’s Medical College Hospital, Bangalore, for his encouragement and support, and Mathew Varghese, Professor, Department of Psychiatry, NIMHANS, Bangalore, for his intellectual inputs into the methodology and design of the questionnaire.

References

- Osler W. Aequanimitas, with other addresses to medical students, nurses and practitioners of medicine. London: H K Lewis; 1904.

- Frick D. Non sexual boundary violations in psychiatric treatment. In: Oldham JM, Riba MB, editors. Review of Psychiatry. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press;1994: 415-32.

- Nadelson C, Notman M T. Boundaries in the doctor patient relationship. Theor Med Bioeth. 2002; 23(3): 191-201.

- Avasthi A, Grover S. Clinical practice guidelines Ethical and legal issues in psychotherapy. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009; 148-63.

- Spickard WA, Swiggart W, Manley G, Samenow CP, Dodd D. A continuing medical education approach to improving sexual boundaries of physicians. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic. 2008;72(1): 38-53.

- Mundakel TT. Blessed Alphonsa. Bombay: The Bombay Saint Paul Society: 2005:25-6.

- Feldman-Summers S, Jones G. Psychological impacts of sexual contact between therapists or other health care practitioners and their clients. J Consult Clin Psychol.1984 Dec;52(6):1054-61.

- Fahy T, Fisher N. Sexual contact between doctors and patients. Almost always harmful. BMJ. 1992 Jun 13; 304 (6841):1519-20.

- Hall RC, Hall RC. False allegations: the role of the forensic psychiatrist. J Psychiatr Pract.2001 Sep;7(5): 343-6.

- Sarkar S P. Boundary violation and sexual exploitation in psychiatry and psychotherapy: a review. Advan Psychiatr Treat. 2004;10:312-20.

- Wilbers D, Veenstra G, van de Wiel HB, Weijmar Schultz WC. Sexual contact in the doctor-patient relationship in The Netherlands. BMJ. 1992 Jun 13; 304(6841):1531-4.

- Dehlendorf CE, Wolfe SM. Physicians disciplined for sex-related offenses. JAMA. 1998 Jun 17;279(23):1883-8.

- Nisselle P. Is self disclosure a boundary violation? J Gen Intern Med.2004 Sep; 19(9):984.

- Cole-Kelly K. Can friends become patients? Am Fam Physician. 2002 Jun 1;65 (11):2390,2392,2395.

- Gutheil TG, Simon RI. Non-sexual boundary crossings and boundary violations: the ethical dimension. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2002 Sep;25(3):585-92.

- Galletly CA. Crossing professional boundaries in medicine: the slippery slope to patient sexual exploitation. Med J Aust.2004 Oct 4;181(7):380-3.

- Simon R. The natural history of therapist sexual misconduct: identification and prevention. Psychiatric Annals.1995;25(2):90-4.

- Bird S. Harassment of GPs. Aust Fam Physician. 2009 Jul;38(7):533-4.

- Lindsey C, Jones D, Holmes J, Shooter M. Vulnerable patients, vulnerable doctors: good practice in our clinical relationships (Council Report CR101). London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2002.

- Kennedy P. Kerr/ Haslam Inquiry into sexual abuse of patients by psychiatrists. Psychiatr Bull R Coll Psychiatr. 2006 Jun; 30 (6):204-6.

- Kluft RP. Treating the patient who has been sexually exploited by a previous therapist. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1989 Jun;12(2):483-500.

- Faunce T, Bolsin S, Chan W-P. Supporting whistle blowers in academic medicine: training and respecting the courage of professional conscience. J Med Ethics.2004;30:40-3.

- Thomas G. Practising medicine in India: some ethical dilemmas. Indian J Med Ethics.2005 Jul-Sep;2(3):88.

- White GE, Coverdale J. General practitioner attitudes toward mandatory reporting of doctor-patient sexual abuse. N Z Med J. 1998 Feb 27;111(1060):53-5.

- Raniga S, Hider P, Spriggs D, Ardagh M. Attitudes of hospital medical practitioners to the mandatory reporting of professional misconduct. N Z Med J. 2005 Dec 16; 118(1227):U1781.

- Pandya S.K. Doctor-patient relationship: the importance of the patient’s perceptions. J Postgrad Med.2001;47(1):3-7.

- Sharon M. Molested at home, humiliated in court, she fights on [Internet]. IBN Live;2009 Sep 17[cited 2010 Mar 9]. Available from http://ibnlive.in.com/news/molested-at-home-humiliated-in-court-she-fights-on/101542-3.html

- Tubbs P, Pomerantz AM. Ethical behaviors of psychologists: changes since 1987. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57(3):395-9.

- Isaac R. Ethics in the practice of clinical psychology. Indian J Med Ethics.2009 Apr-Jun;7(2):69-74.

- Bloch S, Green SA. An ethical framework for psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry. 2006 Jan;188:7-12.

- Medical Council of India [Internet]. New Delhi: Medical Council of India; c2002. Rules and regulations, Code of ethics regulations 2002 ; 2002 Mar 11[cited 2010 Mar 9]; [about 8 screens]. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/know/rules/ethics.htm