DISCUSSION MEDICAL HUMANITIES

Integrating medical education with societal needs

R Krishna Kumar

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2012.058

Introduction

This paper attempts to present a case for serious reforms in medical education with the primary purpose of sensitising future generations of medical graduates to what our society actually needs from healthcare providers. It is not meant to be a scholarly exploration of how healthcare should be provided in our country from the point of view of policy makers or professionals in the field of public health.

While lamenting the unwillingness of our fresh doctors to serve rural populations, I would argue that sensitising them to the need for this during their training will allow them an insight into this dimension of “doing good”, and may motivate them to voluntarily be a part of this vast and important part of rural healthcare in India.

The first part of the article will broadly identify the major failings in healthcare delivery to the average citizen. I will then try and identify how our present medical education system fails to help connect us with the society that we hope to serve. The last part of the article will suggest the way forward and how medical education in India should be restructured.

Background: Indian healthcare delivery

Healthcare delivery in India has been in a state of crisis for many years. This crisis has, however, escaped public consciousness, which is largely occupied by issues brought to the surface by events that attract media attention. For some reason, the total state of chaos and the extraordinary contradictions that exist in healthcare delivery to the average Indian citizen have not been considered important enough to merit a public debate. Most significantly, some of the brightest minds of the country that have chosen to become doctors are completely oblivious to the magnitude of the crisis.

The core issue that underlies this crisis is that Indian healthcare is not organised in accordance with societal needs. In most countries with relatively good human development indices (Cuba, Costa Rica and Sri Lanka are examples), the government healthcare network supports much of the primary and secondary level healthcare. This allows delivery of basic services in accordance with healthcare needs and priorities.

Since independence, the role of government in catering to healthcare needs in India has progressively diminished. More importantly, there is considerable erosion of standards in services provided by the government, together with substantial deterioration of the quality of many medical colleges.

The burgeoning private sector in India was in a position to step in and fill the increasing void left by the government sector. Unfortunately, it has developed like any service sector industry, driven almost entirely by market forces. Even today it remains largely unregulated, aggressively seeking a market for its services. Unfortunately, illness affects everyone regardless of economic condition and most illnesses can be managed without procedures.

Today’s healthcare crisis is a simple reflection of the fundamental disconnect between the actual health priorities of the population and what the existing healthcare delivery system is seeking to provide.

Aspects of the crisis

The examples below illustrate the disconnect between societal needs and the manner in which healthcare is delivered in India.

- Inequity:This is the most striking feature of dysfunction of healthcare delivery in India. Inequity in healthcare manifests itself in stark contradictions: highly sophisticated healthcare facilities co-exist with extreme deprivation of the most basic services. Wide geographical variations in basic health indices are also a manifestation of inequity (1).

- Inappropriate distribution of government subsidies: It is widely known that government subsidies in India do not reach the poorest. Most of the subsidies are consumed by the relatively affluent because of flawed distribution (2).

- Very little emphasis on preventive services at all levels: While preventive services are extremely cost effective, only a small proportion of healthcare providers are actively involved in supplying them. There are few incentives for provision of preventive services in the private sector, and the government sector suffers from poor accountability (3).

- Absence of an effective national programme or policy for many common illnesses that affect Indians, particularly the rural poor(4).

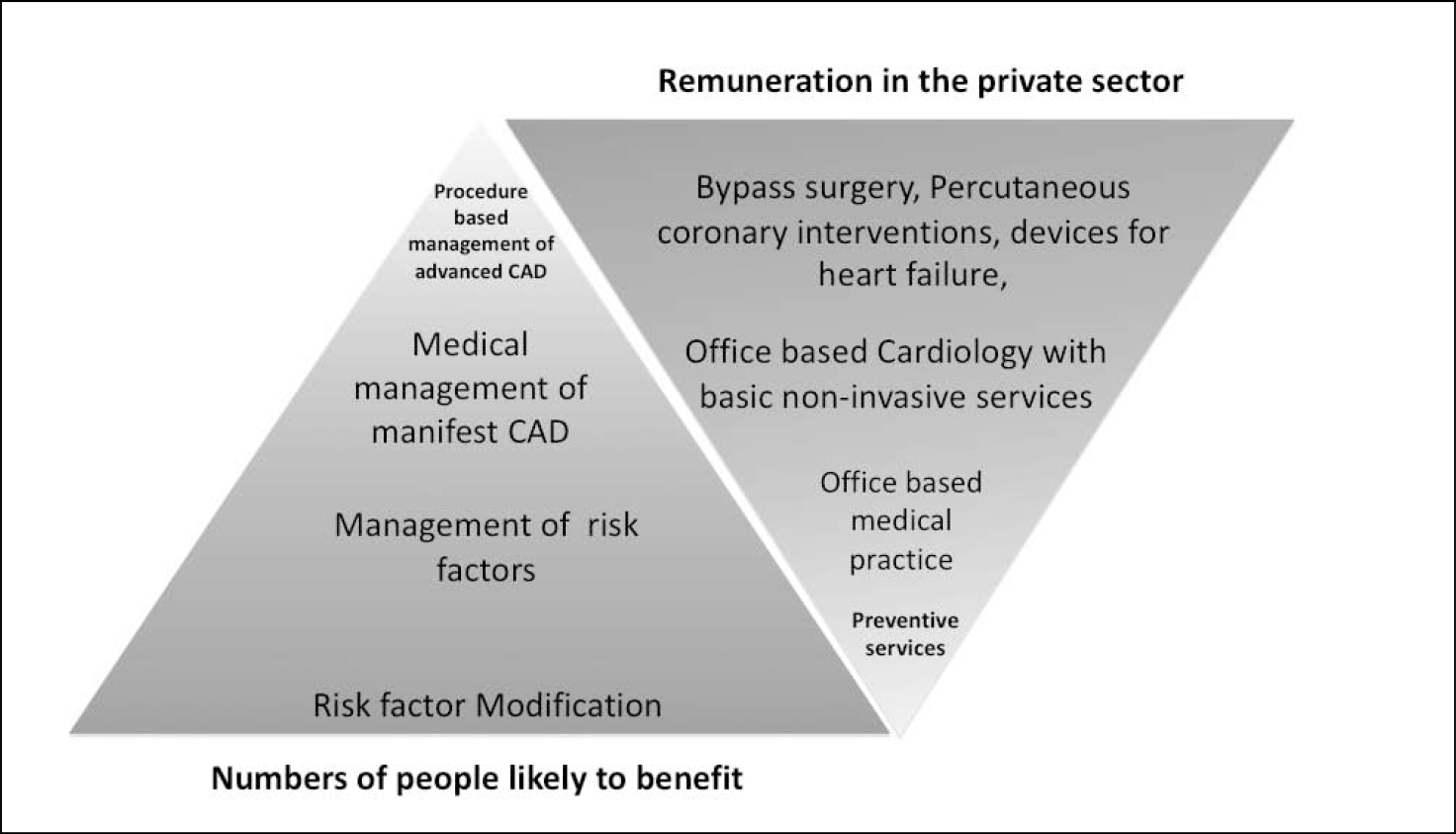

- Disproportionate growth of procedure-based services as against cognitive services, since they offer a much higher compensation (Figure1) (5).

- Inappropriate recommendation of expensive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures for situations with marginal or doubtful benefit (6).

- Wide-spread acceptance of unethical practices:Malpractices such as cut practice for patient referral are no longer considered unacceptable by most members of the Indian medical fraternity today (6).

- Promotion of international medical tourism in the face of serious domestic inequity (7).

Medical education: where it all began

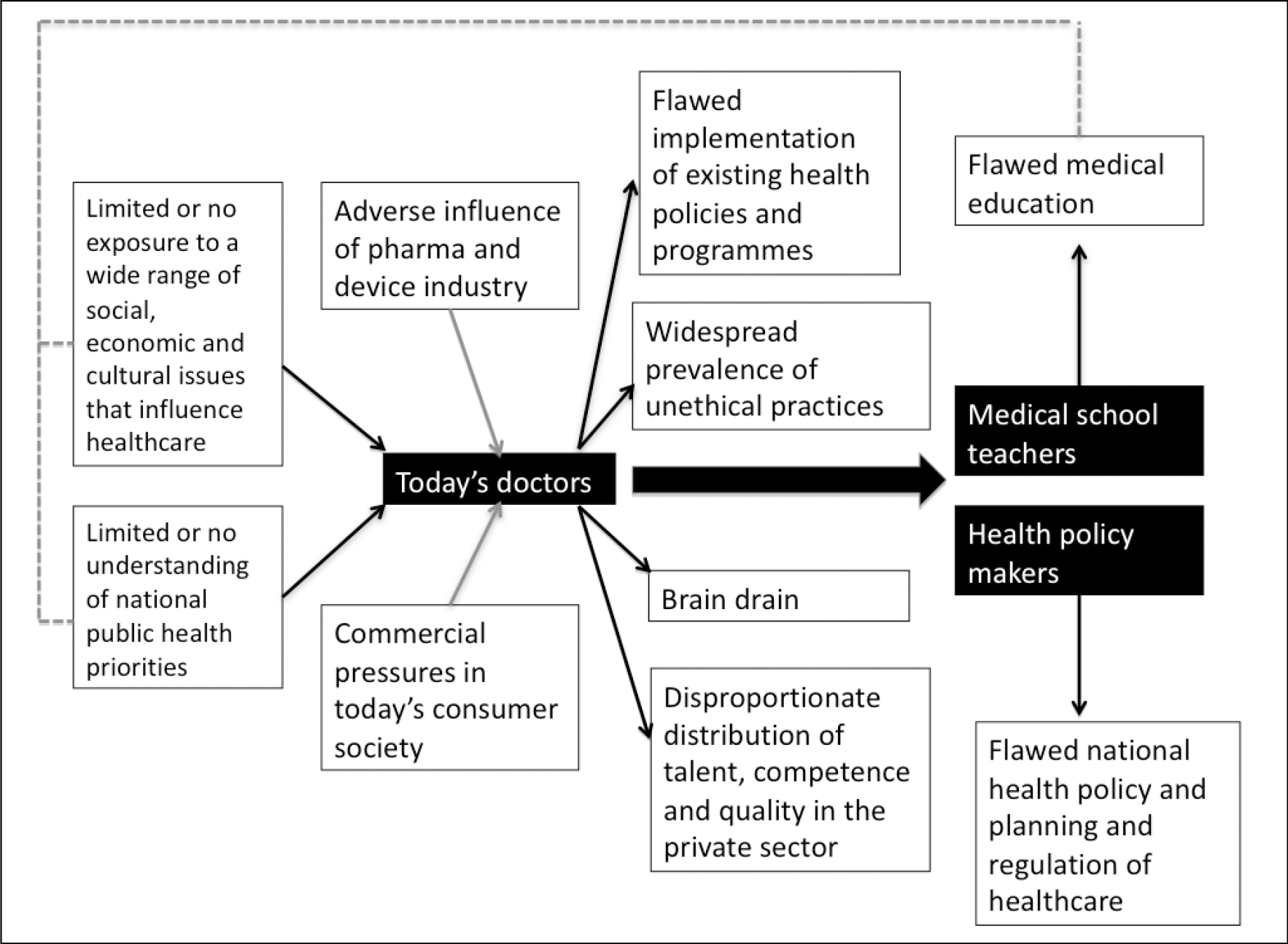

The origins of this deeply dysfunctional situation in our healthcare system canbe traced back to our medical education. The seeds of societal disconnect are sown in the formative years of medical education (Figure 2).

Reflecting on my own years as an undergraduate in Maulana Azad Medical College and as a postgraduate at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, I recall that the brightest among us chose to settle overseas, mostly in the United States and England. The motivation to move out was not necessarily money. All those who left felt that the existing opportunities in India would not satisfy them intellectually. This trend has persisted even when it is increasingly obvious that there are many more opportunities in India, an emerging economy; rather than in the US, wherehealthcare opportunities are on the decline. Very few visualise the prospect of making a much larger impact in the health sector in India where there is a strongly felt need for quality professionals.

It is increasingly apparent that with every generation there is a growing disconnect between our medical students and the society they live in. Why do we, in our formative years, seldom develop a deep desire to serve the society that we live in? Why do medical students graduate without internalising the healthcare priorities of the country? The most academically accomplished young doctors do not necessarily find the health challenges in India intellectually stimulating, and choose to leave the country. Why are we unable to harness their intellect to address the nation’s problems?

Reflecting on my medical school curriculum and the academic environment I grew up in, I realised that the overwhelming emphasis was on acquisition of technical and scientific knowledge. Medical ethics received minimal attention. I do not recall discussing case studies that raised serious ethical questions. We had absolutely no understanding of the microeconomics of healthcare in India. We were completely unaware that the huge expenditureof most familieson healthcareis a major cause of debt in rural families. The serious shortcomings in our national health indices were seldom discussed in detail.

While interacting with patients, we were encouraged to limit ourselves to information that had a bearing on what could have contributed to the patient’s illness. We specifically distanced ourselves from details that the patient and his family were keen to share, if we did not consider them relevant to arriving at a diagnosis. We made little effort to understand the impact of the patient’s illness on his or her livelihood. We often did not try to determine whether his or her economic condition would allow adequate treatment. There were very few role models among senior physicians who displayed and encouraged a high degree of compassion and were seriously interested in the social and economic condition of their patients.

What is the way forward?

What is urgently needed is perhaps not a newer and better technology, but deeper integration of the existing technology with societal needs. Because of the increasing costs and complexity of healthcare delivery, there is a critical necessity to be familiar with the social and economic determinants of healthcare. This can only happen through an understanding of the society we live in. Medical education in its current form does not equip medical graduates to cope with the demands of the increasingly complex healthcare environment of the future.

If we are able to reorient our medical education significantly and start producing a generation of doctors that is sensitive to societal needs, they could potentially contribute to stemming the rot that has set in. A critical mass of enlightened doctors can potentially influence health policy. Policy makers and regulators who emerge from this pool of sensitised doctors can have a strong impact on the health policies of the future.

It is clear that the undergraduate medical curriculum has to be drastically restructured. This can perhaps be realistically achieved over an extended time frame. Such a restructuring will require inputs from a wide range of experts including social scientists, practising doctors, public health experts and health administrators.Tomorrow’s doctors need to be grounded in the cultural, social and economic determinants that influence health and healthcare delivery. More attention needs to be devoted to the most significant national public health priorities, determinants of various national health indices, and rapidly changing lifestyles as consequences of urbanisation and globalisation. The shortcomings and failings of government healthcare delivery structure at all levels need to be emphasised. The role and impact of the private sector, regulations of healthcare, and the micro and macroeconomic impact of heath should also receive emphasis. A wish list of some of the areas that will need to be integrated with undergraduate medical education is listed in the accompanying table.

While postgraduate training could be hospital-based, the focus for undergraduate education should move towards the community. Adoption of representative families by medical students in the region served by the medical college can help create a deep connection with the community. Students could adopt and follow families that have one or more members affected with significant illnesses and obtain a first-hand understanding of how they impact the lives and livelihoods of the affected families. The complexities of healthcare delivery would be apparent and this will help them develop as more insightful and sensitive doctors. A mandated period of rural service can be a life changing experience if carefully supervised. This period can be used by the medical student to develop insights into social and economic determinants of health and the failings of available healthcare delivery systems.

With serious erosion of ethics at all levels, it is vital that tomorrow’s doctors receive comprehensive education in medical ethics. This is perhaps most effectively done through practical case studies. Examples of ethical dilemmas, and ethical violations should be discussed in carefully structured sessions. This should cover medical research and clinical practice. The relationship between the medical fraternity and the device and pharmaceutical industry should be discussed.

A wish list of disciplines and subjects for inclusion in medical college curricula of the future

National health indices

- Relationship of health indices to human development

- Regional variations (geographic inequity)

- International comparisons

Social, economic and cultural determinants of health

- Education, income, specific cultural practices

Health systems

- Governmental health systems: structure, organisation, and shortcomings

- Alternative providers: private sector, NGOs

- Inequity in healthcare

Regulation of Indian healthcare

- Medical Council of India: original role envisioned and actual impact

- Other regulatory authorities: drug controllers, state medical council

- Regulation of hospital and clinics

Ethics in medical practice and clinical research

- Relationship of the medical fraternity with the healthcare industry

The economics of healthcare

- Government and private insurance providers

- Microeconomics: impact on individual families

- Models of cost-effective medicine

Healthcare planning and policies: core principles

- Defining health priorities and resource allocation

Practical training and workshops

- Communication with patients and their families

- Case studies in ethical dilemmas

- Case studies in ethical violations

- Economic and social impact of illness on individuals and families

The lost art of communicating with patients needs urgent attention. Medical students need to be taught how to communicate with patients on a wide range of issues. In the 28 years that have elapsed since I graduated, I have consistently learnt that it is richly rewarding to get seriously interested in our patients’ lives. This is something that traditional medical education does not necessarily encourage. Some questions that we seldom ask when we evaluate patients are actually of tremendous importance. A few examples could be: How far did you have to travel to get here? How is your family coping with your illness? How will your family cope till you recover? How will you pay for your treatment?

A genuine and heartfelt enquiry into the lives of our patients almost invariably helps us connect emotionally with them. This may transform relationships, establish a great deal of trust and eventually enable a much better outcome.

There are successful models of affordable healthcare delivery that have been developed in India. The Aravind Eye Care System is a good example of an innovative network that can be afforded by those living at the bottom of the economic pyramid (8). There are also successful examples of low cost medical implants developed and manufactured in India, such as the Jaipur foot (9) and the Chitra heart valve (10). These accomplishments should serve as a source of inspiration for many of today’s medical students. There are a number of examples of innovations in healthcare that do not find their way into the mainstream consciousness of medical students. It is necessary to contextualise our curricula not just to identify our unique healthcare needs, but also to identify and study successful innovative practices in affordable healthcare in India and the rest of the developing world.

A number of additional measures are worth considering. A system that uses the services of a large number of medical graduates to deliver primary healthcare appears to be an attractive prescription for some of the failings of our health systems. Unfortunately, most state governments have failed to implement compulsory service among under-served populations for medical graduates. The virtual collapse of primary healthcare networks in many areas of the country does not allow for adequate supervision of care delivered by inexperienced doctors. It may be worth exploring the possibility of a mandated rural service of medical graduates after a thorough examination of specific shortcomings that come in the way of successful implementation.

Conclusion

The crisis in healthcare in India today stems from a serious disconnect between healthcare delivery and societal needs, the roots of which can perhaps be traced back to seriously flawed medical education. This can only be remedied through a drastic restructuring, with thoughtful inputs from a wide range of disciplines that includes sociology, economics, ethics and public health.

References

- Balarajan Y, Selvaraj S, Subramanian SV. Health care and equity in India. Lancet. 2011Feb 5;377 ( 9764) :505-15. Epub 2011 Jan 10.

- Mahal A, Yazbeck A, Peters D, Ramana GNV. The poor and health service use in India. Washington, DC: World Bank: 2001.

- O’Donnell O, van Doorslaer E, Rannan Eliya RP, Somanathan A, Adhikari SR, Harbianto D, Garg CC, Hanvoravongchai P, Huq MN, Karan A, Leung GM, Ng CW, Pande BR, Tin K, Tisayaticom K, Trisnantoro L, Zhang Y, Zhao Y. The incidence of public spending on healthcare: comparative evidence from Asia World Bank Econ Rev. 2007; 21(1): 93-123.

- Patil AV, Somasundaram KV, Goyal RC. Current health scenario in rural India. Aust J Rural Health. 2002;10:129-35. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1584.2002.00458.x

- Gangolli LV, Duggal R, Shukla A. Review of healthcare in India [Internet]. Mumbai: Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes. 2005[cited2012 May13], Available from: http://www.cehat.org/go/uploads/Hhr/rhci.pdf

- Yesudasan CAK, Behaviour of the private sector in the health market of Bombay, Health Policy Plan. 1994;9(1):72-80. doi 10.1093/heapol/9.1.72

- Sengupta A. Medical tourism in India: winners and losers. Indian J Med Ethics. 2008 Jan-Mar:5(1):4-5.

- Rangan VK, Thulasiraj RD. Making sight affordable (Innovations case narrative: The Aravind Eye Care System). Innovations. 2007 Fall;2(4):35-49.

- Sethi PK, Udawat MP, Kasliwal SC, Chandra R. Vulcanized rubber foot for lower limb amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1978 Dec;2(3):125-36.

- Bhuvaneshwar GS, Muraleedharan CV, Vijayan GA, Kumar RS, Valiathan MS. Development of the Chitra tilting disc heart valve prosthesis. J Heart Valve Dis. 1996 Jul;5(3):448-58.