ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Iatrogenic error and truth telling

Shishir Kumar Maithel

A comparison of the United States and India, by Shishir Kumar Maithel

At the core of the doctor-patient relationship must lie a feeling of trust between the two. If a patient does not trust his/her physician, then the physician’s effectiveness is greatly compromised. Patients must know that their physicians have their best interests in mind and are telling the truth about their illness and progress. The physician is also ethically obliged to report the truth to the patient, the exact extent being debatable among different cultures.

The history of literature on medical truth telling dates as far back as 1803 when Thomas Percival wrote that “to a patient, who makes inquiries which, if faithfully answered, might prove fatal to him, it would be a gross and unfeeling wrong to tell the truth” (1). This view can be contrasted with, for instance, that of Saul S Radovsky who writes that “doctors are not wise enough to tell in advance who should not be told [and] that shielding is ultimately impossible and that the price of its temporary achievement is an enduring sense of betrayal. Once lied to, even supposedly in their own interest, people will not trust fully again” (2). The trend, from withholding information to telling the truth, is supported by surveys which show that in 1985 at least 70 percent of physicians now believe in telling patients about their cancers as opposed to 12 percent just 24 years ago (2). It is safe to say that most people want their doctors to tell them the truth. The only concern is the manner in which it is disclosed. As Norman Cousins writes, “The real issue is not whether the truth should be told but whether there is a way of telling it responsibly. Certainly it should not be allowed to become a battering ram against the patient’s morale, impairing his ability to cope with the greatest challenge of his life” (3).

One subject of much discussion is whether or not to reveal iatrogenic error. Many physicians are reluctant to inform their patients of their mistakes. In a study of house officers in the US, the patient and/or family was informed of the mistake only 24 per cent of the time (4). Patients, on the other hand, want to be told of any mistakes. In another study, 98 per cent of the patients surveyed “desired or expected the physician’s active acknowledgement of an error” (5). Legal concerns, such as fear of law suit, are considered to be a major reason for physicians withholding information from their patients. However, the same study found patients nearly twice as likely to report or sue their physician if they discovered the mistake independently (5). Thus, it may be in the physician’s best interest to just tell the truth.

There is no universal standard for truth telling. The exploratory study reported here compares the Indian and US systems, specifically on the issues of whether iatrogenic error affects treatment decisions and how mistakes are handled. I expect that fewer Indian physicians would choose to resuscitate a terminally-ill patient who suffers a cardiac arrest, and fewer Indian physicians would choose to disclose and error to the patient and /or family.

Methods

A questionnaire was distributed to convenience samples of physicians in New Delhi, India, at the Indraprastha Apollo Hospital Outpatient Department, and in the US at the University of Chicago Hospitals in Chicago, Illinois.

The questionnaire opened with a clinical case vignette, based on a model developed for another study by Dr. David Cassarett, which presented the physicians three possible scenarios:

- A 75-year-old, terminally-ill patient suffers a cardiac arrest.

- A 75-year-old, terminally-ill patient suffers a cardiac arrest as a result of an unknown allergy to a prescribed antibiotic.

- A 75-year-old, terminally-ill patient suffers a cardiac arrest as a result of a known (by the physician), but forgotten, allergy to a prescribed antibiotic. In each case, the physician is asked whether or not he/she would resuscitate the patient.

This case vignette is designed to reveal any differences in resuscitation decisions when the cardiac arrest is due to iatrogenic error.

The second part of the questionnaire addressed issues such as:

- Who is informed when a mistake is made?

- Are there any legal issues which are of concern when revealing iatrogenic error?

- Was any training received in medical school on how to handle mistakes?

Results

Physicians at Indraprastha Apollo Hospital in New Delhi, India

Of a total 86 Indian physicians available, 41 were approached and 40 complete questionnaires were obtained. Their age ranged from 28 to 60 (mean = 41) years old, and the number of years in practice varied from 1 to 36 (mean = 14) years. 82.5 per cent of the surveyed physicians were male. 34 had received a majority of their training in India while 6 received it in Britain. The majority of physicians were specialists in internal medicine.

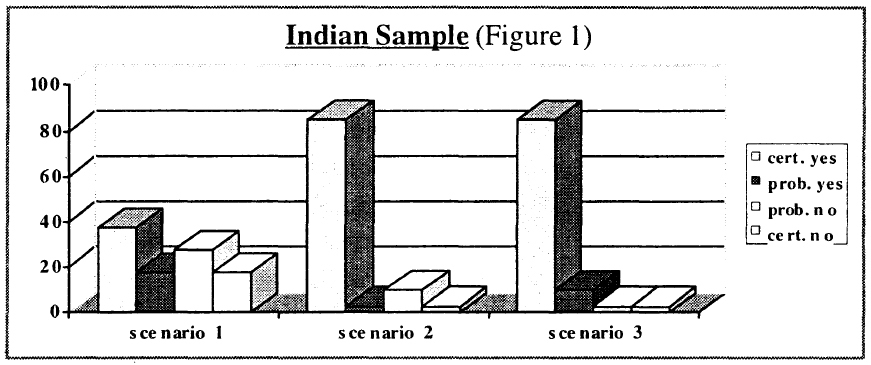

When asked whether they would resuscitate a terminally ill patient, with at most a few weeks to live, who suffers from cardiac arrest (scenario 1), 55 per cent responded that they ‘certainly’ or ‘probably’ would. However, when the cardiac arrest resulted from an unknown allergy to a prescribed antibiotic (scenario 2), the percentage increased to 87.5 per cent. When the allergy was known, but merely forgotten by the physician (scenario 3), the percentage who would resuscitate climbed to 95 per cent, which is all but two physicians (Fig.1).

There was no significant difference between scenarios 2 and 3, suggesting that the physicians were assuming similar responsibility when the allergy was unknown (scenario 2) and when they forgot about the allergy (scenario 3). This may imply that the physicians considered the cardiac arrest to be iatrogenic in both scenarios 2 and 3. The most popular explanation provided by the physicians in their responses was that they were ethically bound to resuscitate and felt a sense of moral duty when the cause of cardiac arrest was iatrogenic in nature.

The next question was if there was an office to which they should report a medical error. Twenty-three (57.5 per cent) responded that no such department existed. Of the 17 physicians who said yes, a variety of answers, including the ‘director of medical services’ were given when asked to name the office.

Seventy-five percent of the physicians practising in India responded that they would report an error to the patient, and 72.5 per cent said they would report to the patient’s family as well. The most common reason for disclosure expressed by the physicians was their sense of ethical duty to be honest with the patient and family. The second most popular reason was that the physicians wanted to discuss the possible complications resulting from the error. Only five physicians would not reveal an error to a patient and five said that it depended on the situation. Thirty-six physicians, or 90 per cent, expressed some concern for legal issues when revealing an error. Because of the recently passed Consumer Protection Act in India, 27 physicians specifically mentioned their fear of a law suit.

Sixty-five percent of the physicians had not received any instruction in their medical training on how to handle a mistake, which interestingly included all six physicians who had received a majority of their training in Britain.

However, when asked to whom a physician is obliged to report an error, the three most common responses were: (1) hospital authorities (2) patient and family (3) medical director or senior physician in charge. Shockingly, 87.5 per cent of these physicians felt this ‘almost never’ happened, and if it did, only ‘less than half’ of the time.

Physicians practising at University of Chicago Hospitals in Chicago, Illinois

Fifty-three physicians were approached at the University of Chicago Hospitals, and 40 completed surveys were obtained. The age of the physicians ranged from 26 to 75 (mean = 38) years old, and the number of years in practice ranged from 1 to 40 (mean = 9.5) years. Sixty percent of the physicians surveyed were male. The majority of physicians were specialists in internal medicine. 36 received a majority of their training in the United States, one received it in India, and three studies in other countries.

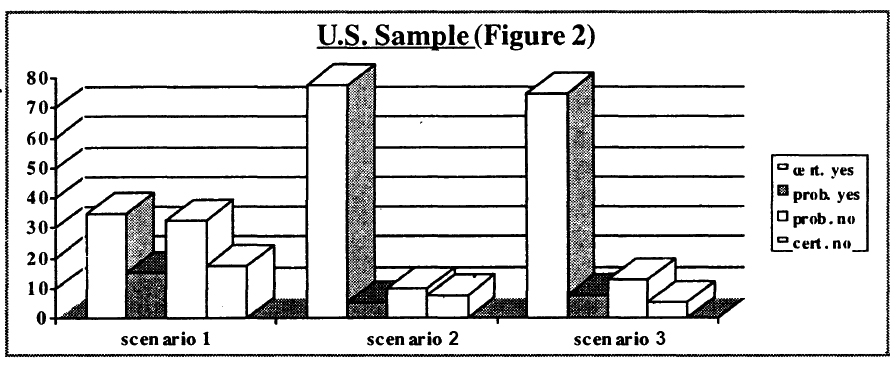

When asked about the terminally ill patient, scenario 1 revealed that 50 per cent ‘certainly’ or ‘probably’ would resuscitate the patient. The percentage increased to 82.5 per cent for both scenario 2 and scenario 3. (Fig. 2).

Again, there is no difference between the results of scenarios 2 and 3. The physicians expressed an obligation to resuscitate the patient, especially when the cause of the cardiac arrest was iatrogenic in nature.

Eighty-five percent (34 physicians) of the U.S. physicians said that there was an office to which to report medical errors, and an overwhelming majority of them agreed that it was the medico-legal (risk management) department.

Ninety percent (36 physicians) said that they would report an error to the patient, and 75 per cent would reveal the error to the patient’s family. As with the Indian physicians, a sense of moral duty to be honest with the patient and family was the motivation. The decrease in percentage to reporting to the family may be explained by the opinion of some physicians that it is the patient’s decision whether or not to tell the family. 34 physicians, or 85 per cent, expressed some concern for legal issues when disclosing the error, of which all but two specifically mentioned the fear of a malpractice law suit.

Fifty percent of the physicians said their medical training did not include instruction on how to handle mistakes. However, when asked to whom a physician is obliged to report an error, the majority agreed that the patient should be informed. Compared to the 87.5 per cent of Indian physicians, only 52.5 per cent o the U.S. physicians felt that this rarely or almost never happened.

Conclusion

Except for two of the survey questions, the responses of the Indian and U.S. physicians did not differ significantly.

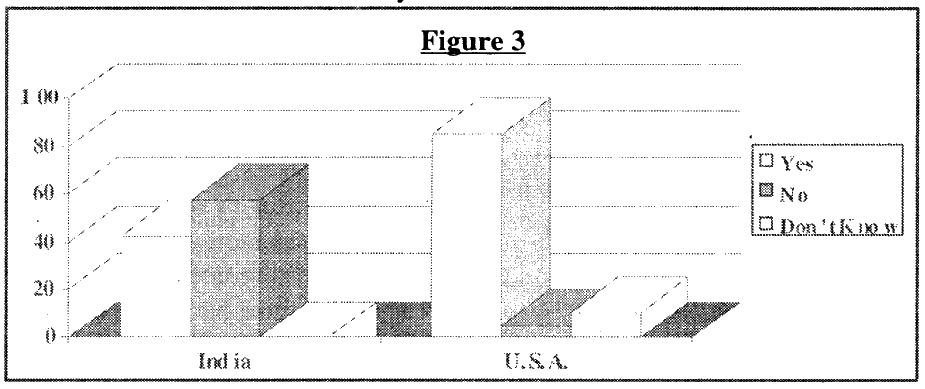

One difference was when the physicians were asked whether or not an office / department existed in the hospital to which to report a medical error. Twice as many US as Indian physicians said that such a department existed. (Fig. 3).

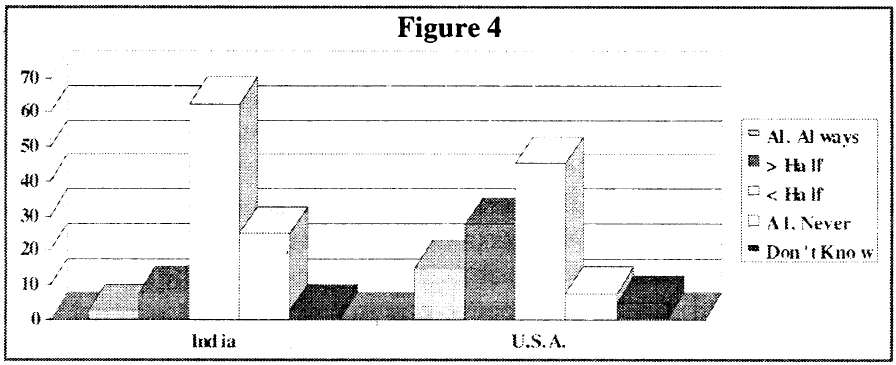

The second major difference was on how often physicians in the two countries felt medical errors were reported. In India, 87.5 per cent of the physicians felt that it happened ‘less than half’ to ‘almost never’ of the time as compared to 52.5 per cent of the U.S. practicing physicians (Fig. 4).

Discussion

The similarities between the physicians’ responses is striking, and unexpected. This study was conducted with the expectation that physicians in the US would be more likely to resuscitate than those in India, mainly because the U.S. has more resources and its legal system encourages resuscitation. It was also believed that in India, physicians would be less likely to resuscitate a 75-year-old, terminally-ill patient because of cultural/spiritual beliefs. In fact, the actual percentages of resuscitation were higher, though not significantly for the Indian sample.

It was also believed that the U.S. emphasis on having informed patients and the emphasis on truth-telling as a part of ethical medical practice would encourage US physicians to disclose errors to the patient and / or family.

However, similar percentages of Indian and U.S. physicians responded that they would discuss the error with the patient and/or family. The Indian physicians also had the same legal concerns and a similar percentage had received training on how to handle mistakes.

This exploratory study thus serves to point our similarities between the two countries. One cannot assume that a developing county with limited resources will differ in every aspect when compared to a rich country. The results suggest that at least these two samples of physicians share a common mentality and protocol when dealing with iatrogenic error and truth telling.

However, the significant differences mentioned suggest that the Indian medical system is not as prepared and equipped to handle legal affairs as is the U.S. medical system. In the United States, malpractice suits are common. Thus, the University of Chicago Hospitals have invested the time, money, and man-power to create a department to handle legal affairs and protect physicians. Physicians are aware of this support, perhaps encouraging them to say that the proper authorities / people are informed of a medical error. However, malpractice suits are relatively new in India. Hospitals may not be prepared to handle such extensive legal affairs, explaining why fewer Indian physicians reported that such an office existed, the variety of responses on which the office was, and why fewer Indian physicians feel the need to report a medical error.

While the small convenience samples and sensitive issues addressed prevent generalisation of these conclusions, these findings suggest that cultural differences, and similarities, exist and are not necessarily what we would expect these to be.

The author would like to acknowledge the contributions of Carol B Stocking, PhD, and the MacLean Center for Clinical Studies.

References

- Leake CD, ed. Percival’s medical ethics. Baltimore: Williams of Medicine 1927:186-96

- Radovsky, Saul S. Bearing the news. New England Journal of Medicine 1985; 313: 586-88

- Cousins, Norman. A layman looks at truth telling in medicine. JAMA 1980; 244: 1929-30

- Wu, Albert W.et a.l. Do house officers learn from their mistakes? JAMA 1991; 265:2089-94

- Witman, Amy B. et al. How do patients want physicians to handle mistakes? Archives of Internal Medicine 1996; 156:2565-69