COMMENT

Ethics education for contemporary clinical pharmacy practice in Africa

Roland N Okoro, Muslim O Jamiu

Published online on September 20, 2019. DOI:https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2020.098Abstract

The paradigm shift to a patient-centred pharmacy practice model has resulted in dramatic increases in the number and variety of ethical and other dilemmas that confront pharmacists in their routine practice. However, ethical problems may go undetected by many pharmacists in most developing countries. Hence, there is a huge need for sound educational preparation of future pharmacists before they are faced with an urgent decision. This paper highlights the urgent need for pharmacy ethics to be adequately taught in schools of pharmacy, especially at the undergraduate and professional levels, so that future pharmacists can begin their professional careers with adequate ethical knowledge, skills, competencies and experience to detect and resolve ethical dilemmas of the contemporary patient-centred pharmacy practice.Keywords: clinical pharmacy, pharmacy education, pharmacy ethics, pharmacy practice

Introduction

Professional pharmacy practice in community and hospital settings is most common in African countries, including South Africa, Botswana, Kenya, Nigeria (1, 2, 3, 4), among others. As frontline health workers, African community pharmacists provide health screening, family planning, and emergency care services for minor illnesses (5), and also offer a full range of prescription and non-prescription medication services (1). On the other hand, hospital pharmacists have a range of duties and responsibilities, such as administration, medication management, participation in drug therapeutic committees, medication procurement and dispensing, drug information provision, sterile and non-sterile compounding, pharmacovigilance activities, and hospital-based research (2). From the foregoing, it is evident that community and hospital pharmacies settings constitute infrastructural bases for the implementation of pharmaceutical care in Africa. Pharmacy practice has evolved over time from apothecary (primordial times) to compounding (1940s) to distribution (1950s) to clinical pharmacy (1960s) and recently to pharmaceutical care (1990s) (6). Pharmaceutical care is a new model of pharmacy practice geared towards optimising patient health outcomes. However, pharmaceutical care as one of the extended roles of clinical pharmacists has resulted in an upsurge in the number and variety of ethical dilemmas that confront clinical pharmacists. Hence, to be able to detect these ethical dilemmas or resolve them appropriately while providing pharmaceutical care, pharmacy students should be well equipped with the knowledge and skills of healthcare ethics.

Pharmacy ethics has traditionally held a very small place in the scheme of pharmaceutical education, relegated to formal talk and sharing of copies of code of ethics for new pharmacists on the eve of their induction (7). However, previous studies appeared to cast doubt on the relevance of a pharmacy code (8, 9). Pharmacists often struggle to describe ethical situations and this has been demonstrated in lack of ethical analytical skills among them (10). Although pharmacy is not usually involved in some of the more high profile ethical issues that arise in medicine such as ethical concerns about conjoined twins, transplantation and the pre-selection of embryos to eradicate genetic diseases, in vitro fertilisation and gender selection, among others (10). This may have contributed to the neglect of an ethical focus on pharmacy as compared with the more dramatic areas of healthcare such as medicine. Because pharmacists now have close interactions with patients via pharmaceutical care and are considered as an indispensable group of healthcare providers, ethics in pharmacy practice seems to be as important as in medicine. The problem of legal liability, actual and imagined, affects the actions of physicians and pharmacists as each tries to maximise patient care and minimise legal liability.

In comparison with medicine, relatively little research has considered ethical concerns in pharmacy, despite the paradigm shift to pharmaceutical care with an increasingly important ethical dimension, thereby highlighting the need for a refocusing on the ethical dimension of the pharmacist’s new patient-centred role and on sound ethical education to prepare pharmacists for that role.

Pharmacy ethics education in Africa

A pharmacy graduate is primarily required to be able to recognise ethical dilemmas in healthcare and science and understand the ways in which these might be managed by healthcare professionals in the light of the relevant laws (11). In view of this, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education of the US prescribes that “the college or school of pharmacy must ensure that the curriculum fosters the development of professional judgment and a commitment to uphold ethical standards and abide by practice regulations” (12). Similarly, the US Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education requires that “pharmaceutical care be provided based upon sound therapeutic principles and evidence-based data, taking into account relevant legal, ethical, social, economic, and professional issues” (13). Furthermore, the General Pharmaceutical Council, the accrediting body for the master of pharmacy (M Pharm) degree programme in the UK, requires “pharmacy students to recognize ethical dilemmas and respond in accordance with relevant codes of conduct and behaviour” (14). Hence, ethics should be a critical part of pharmacy curricula around the world to equip future pharmacists with ethical knowledge and competencies for their real-world pharmacy practice.

Disappointingly, undergraduate/professional pharmacy ethics education in most parts of the world predominantly deals with the legal aspects of pharmacy practice, with pharmacy ethics receiving far less coverage in the curriculum. Additionally, pharmacy law and ethics are usually combined as a single course taught didactically only.

The Nigerian undergraduate pharmacy ethics syllabus is included in a forensic pharmacy and pharmacy ethics single course for the Bachelor of Pharmacy (B Pharm.) programme as approved by the country’s regulatory body for higher education (15). This course is dominated by pharmacy law with the ethics of the pharmacy profession in Nigeria, and ethics and good business practice as the only ethics topics. Against this background, pharmacy ethics is not taught to students because no curricular time is assigned to it in most Nigerian pharmacy schools.

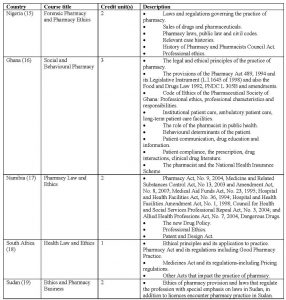

A quick review of the undergraduate pharmacy curricula of some schools in Africa revealed a similar trend (Table 1). For example, the pharmacy school at the University of Ghana has ethics included in the social and behavioural pharmacy course (16). This course is overloaded with so many aspects of pharmacy practice including pharmacy law, pharmacists in primary healthcare, among others that have no capacity to impart any meaningful ethical knowledge, awareness and skills to students for clinical pharmacy practice on graduation. In Namibia, the school of pharmacy at the University of Namibia includes the pharmacy ethics syllabus in a combined pharmacy law and ethics single course (17). As expected, the pharmacy ethics syllabus of this course is far from being well-developed. Professional ethics is the only ethics topic contained in this combined single course. Also in South Africa, pharmacy ethics is not well-developed, as evidenced by the health law and ethics combined single course of the school of pharmacy at the University of KwaZulu-Natal which has ethical principles and its application to practice as the only ethics topics (18). Finally, in Sudan, the ethics and pharmacy business combined course of the School of Pharmacy at Ahfad University for Women also reveals a shallow ethics content. The ethics of pharmacy provision is the only ethics topic of this course (19).

Table 1: B Pharm programme pharmacy law and ethics syllabi of some African countries

From the foregoing, it is evident that the curricula of pharmacy education in Africa contain law and ethics as a single course with pharmacy law being the dominant component. However, in pharmacy practice, law and ethics share many similar characteristics while fulfilling separate, but occasionally overlapping functions in regulating pharmacist’s behaviour (20). This combination has created room for ethics syllabi to be underdeveloped and relegated to the background. Additionally, it leads to ethical issues being entwined with legal issues. When taken together as a single course, without doubt, students will often will become confused in trying to differentiate between legal and ethical principles when deciding what type of conduct is mandated by law or expected as part of ethical service. In order to address these shortcomings, a model for pharmacy ethics education is proposed here by the authors of this paper.

A proposed model for pharmacy ethics education in Africa

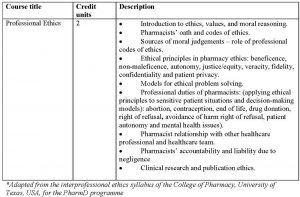

The goal of ethics education is to provide ethical knowledge, skills and competencies. This must be kept in mind when the content of an ethics syllabus is determined. Therefore, a standalone pharmacy ethics course is proposed to make room for a well-developed pharmacy ethics education, with deeper content and diverse modes of delivery that will ensure the ethical development of future pharmacists. Since, the skill in question here is that of critical ethical thinking, part of the content must be ethical theory balanced with laboratory experience, such as the involvement of students in concrete ethical problems so that the skill of ethical thought may be learned. This is because models for ethics education should include both a theoretical and a practical component in the form of case debate, case discussion, small group discussion and team-based learning. This innovative strategy has the capacity not only to enrich pharmacy students with professional, ethical reasoning but also with cultural perspectives of ethical problems.

Table 2: A proposed model for a pharmacy ethics syllabus (21)*

Conclusion

Currently, the undergraduate pharmacy education in Africa predominantly deals with the legal aspects of the pharmacy practice compared with ethical aspects. Therefore, improving pharmacy ethics education by adopting a standalone pharmacy ethics course is critical to providing the best pharmaceutical care and making sound ethical clinical decisions at all times. A well-developed, culturally adapted standalone pharmacy ethics syllabus is highly recommended to pharmacy educators in Africa to help overcome the traditional dominance of law in the existing pharmacy law and ethics combined single course of most schools of pharmacy.

Declaration regarding prior publication of similar work: A similar paper that considered the Nigerian scenario only has previously been published by the first author (see Reference 6).

Conflicts of interest and external funding: None declared.

References

- Gray A, Riddin J, Jugathpal J. Healthcare and pharmacy practice in South Africa. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2016 Jan-Feb; 69(1):36-41.

- Awayk D, Jaguga CDP, Nkonge NG, Kinuthia R, Ambale C, Awle IA. Pharmacy Practice in Kenya. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2017 Nov-Dec;70(6):456-2.

- Ekpenyong A, Udoh A, Kpokiri E, Bates I. An analysis of pharmacy workforce capacity in Nigeria. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2018;11: 20, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-018-0147-9.

- Drame I, Connor S, Hong L, Bimpe I, Augusto J, Yoko-Uzomah J, et al. Cultural sensitivity and global pharmacy engagement in Africa. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019 May; 83(4):7222.

- Malangu N. The future of community pharmacy practice in South Africa in the light of the proposed new qualification for pharmacists: Implications and challenges. Glob J Health Sci. 2014 Nov; 6(6):226-33.

- Okoro RN. Ethics education for contemporary clinical pharmacy practice in Nigeria: Shortfalls and needs. Bangladesh J Bioeth. 2018;10(1):1-5.

- Buerki RA, Vottero LD. Ethical responsibility in pharmacy practice. 2nd ed. Madison, WI: American Institute of the History of Pharmacy; 2002.

- Chaar B, Brien J, Krass I. Professional ethics in pharmacy: the Australian experience. Int J Pharm Pract. 2005;13(3):195-204.

- Hibbert D, Rees JA, Smith I. Ethical awareness of community pharmacists. Int J Pharm Pract. 2000; 8:82-7.

- Cooper R. Ethical problems and their resolution amongst UK community pharmacists: a qualitative study. PhD thesis, University of Nottingham. 2007 [cited 2019 May 10]. Available from: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/10265/1/6gpdf.pdf.

- General Pharmaceutical Council. Step 6 Accreditation of an M Pharm degree course. Report of an accreditation event, University of Ulster, 16-17 May 2012 [cited 2019 May 10]. Available from: https://www.psni.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Ulster-MPharm-accreditation-step-6-May-2012-REPORT-Final-Education-section.pdf.

- Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Chicago, Illinois: ACPE; 2011 [cited 2019 May 10]. Available from: https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/FinalS2007Guidelines2.0.pdf.

- American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education. Educational outcomes 2004. [cited 2019 May 10]. Available from: http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/documents/CAPE2004.pdf.

- General Pharmaceutical Council. Future pharmacists: standards for initial education and training for pharmacists. May 2011. [cited 2019 May 10]. Available from: http://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/GPhC_Future_Pharmacists.pdf.

- Benchmark and Minimum Academic Standards for Undergraduate Programs in Nigerian Universities, Pharmaceutical Sciences. Nigerian University Commission. 2018. Available from: https://www.pcn.gov.ng/files/BMS.pdf

- University of Ghana, Department of Pharmacy Practice and Clinical Pharmacy. Course Schedule. 2014 [cited 2019 Aug 25]. Available from: http://www.ug.edu.gh/ppcp/academics/course_schedule.

- Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Pharmacy, University of Namibia, Prospectus 2019 [cited 2019 Aug 25]. p 30. Available from: https://www.unam.edu.na/newsletter/school_of_pharmacy_prospectus_2019.

- University of KwaZulu-Natal, College of Health Sciences, Handbook for 2018. [cited 2019 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.saa.ukzn.ac.za/files

- Ahfad University for Women Undergraduate Catalogue 2016-17 & 2017-18 [cited 2019 Aug 25]. p 163. Available from: https://www.ahfad.edu.sd/images/2017/PDF/AUW-Undergraduate-Catalogue.

- Gallagher CT. Building on Bloom: A paradigm for teaching pharmacy law and ethics from the UK. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2011;3(1):71-6.

- University of Texas College of Pharmacy. Pharm. D. Curriculum. [cited 2019 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.pharmacy.utexas.edu/students/programs-of-study/pharm-d-program/pharm-d-ccurriculum.