COMMENT

Enhancing the autonomy of Indian nurses

Meena Putturaj, Prashanth NS

Published online: May 30, 2017

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2017.058

Abstract

With additional training and qualification, nurses in several countries are recognised as independent professionals. Evidence from several countries shows that capacitating nurses to practise independently could contribute to better health outcomes. Recently, the idea of nurses practising independently has been gaining momentum in Indian health policy circles as well, and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare is contemplating the introduction of nurse practitioners (NPs) in primary healthcare. We briefly assess the policy environment for the role of NPs in India. We argue for the need to conceptualise health stewardship anew, keeping the nursing profession in mind, within the currently doctor-centred health system in India. We argue that, in the current policy environment, conditions for independent nursing practice or for the introduction of a robust NP in primary healthcare do not yet exist.

Nurses constitute a major proportion of the health workforce, and some of the innovations in health workforce management across the globe have focused on task shifting to non-physician health workers, such as nurses, to decentralise and transform the health system. Apart from playing their traditional roles, nurses in a few countries are performing extended roles with titles such as advanced practice nurse, nurse practitioners (NPs), clinical nurse specialists and nurse anaesthetists. Nurses practise independently in several high-income countries, such as the USA, Australia, Canada, Ireland, the UK, Finland and the Netherlands, and even in some middle- and low-income countries, such as Thailand and Nigeria. In some of the provinces of these countries, the nurses need to have collaborative practice agreements with the physicians to practise independently. There is evidence across the globe to show that NPs are increasingly being used as the point of first contact and that patients are as, or more, satisfied with NPs than doctors (1, 2). The cost of health service is also lower with NPs. Several studies have found that there is no difference between the clinical outcomes with NPs and general practitioners (1, 2).

In recent times, the concept of independent practice by nurses has gained significant momentum within India’s health policy circles as well. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) is contemplating the introduction of NPs in primary healthcare and is already in consultation with the Indian Nursing Council (INC – the national regulatory body for nurses and nursing education) and other stakeholders to take the move forward. The aim of this article is to examine the issues involved in independent nurse practice and its relevance in India.

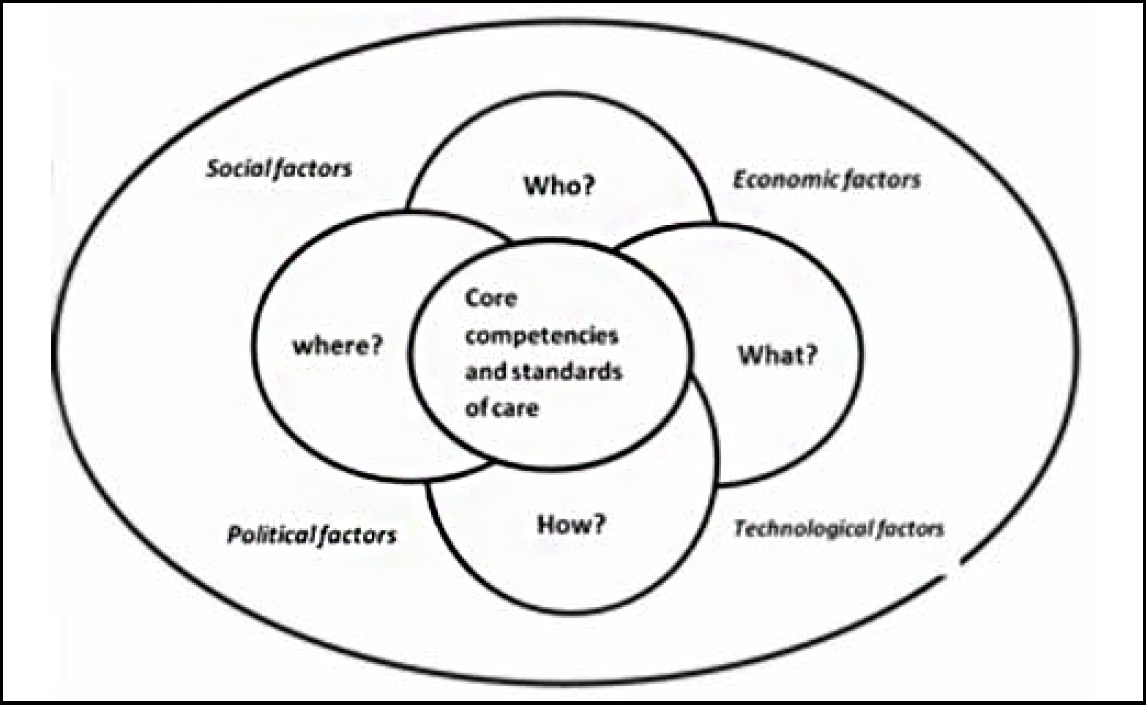

Conceptual framework for independent NPs and comparison of the NP course in critical care with the proposed framework

There are a few frameworks in the literature that conceptualise the role of NPs. The Schuler NP practice model (3), conceptual models by the International Council of Nurses (4), and the Ardene and Ruth model (5) are a few that define the provision of care by NPs. The Gest et al model (6) focuses on an analysis of advanced nurse practice roles. It identifies five drivers of the influence of NPs: (i) healthcare needs of the population, (ii) legal, policy and economic context, (iii) practice patterns, (iv) workforce issues, and (v) education. In countries such as India, where an independent nursing practice is not in place, and where nursing education and practice are hampered by several regulatory and quality-related issues, frameworks on NPs to guide policy should be broader and draw upon other factors in the health system as well. We describe a broader framework.

The INC is working on the curriculum for the course on NP in primary healthcare. While the MoHFW is in the initial stages of developing the course in primary care, the INC has already put up a detailed notification on its official website, inviting applications from nursing colleges to start courses on NP in critical care (7). The main aim of this course, which has been rolled out recently, is to prepare graduate nurses for advanced practice roles as clinical experts, managers, educators and consultants, which would lead to an MSc degree in critical care NP. If we carefully analyse the curriculum of the NP course in critical care, we find that a few of its aspects are aligned with the conceptual framework mentioned above, but many others are deficient.

The role of NPs is influenced by the healthcare demands of the population, and also by social, political, economic and technological factors. At the heart of the framework are the core competencies and standards of care that the proposed NP training will focus on. All the building blocks of our framework are ranged around the central pillar of the NP’s role. There is a need to define the scope of practice, standards of care and core competencies of NPs in their respective area of practice. The current syllabus for the NP course in critical care identifies the core competencies and scope of NP practice in critical care settings. The proposed NP course in critical care requires graduate nurses to be trained to independently/collaboratively administer drugs and therapies, order diagnostic tests and procedures, and handle medical equipment according to the institutional protocols and standing orders. The curriculum is designed in such a way that the clinical component accounts for 85% and theory classes for 15%.

- Who will the NP be? The entry-level criteria and educational qualifications of NPs should be clear. According to the regulations stipulated by the INC for the course on NP in critical care, registered graduate nurses with one year’s clinical experience, preferably in the critical care setting, are eligible to apply.

- Where will the training take place? This refers to the educational institutions and the adequacy of their standards for running courses for NPs. According to the INC, institutions running graduate and postgraduate nursing programmes with a parent tertiary care centre (minimum of 220 beds) can apply for starting a course on NP in critical care. Certain norms have been relaxed for the institutions to start the course. For example, if the institution is running a DNB programme, it does not require a no-objection certificate from the state government. In these times, when nursing colleges are mushrooming and the quality of nursing educational institutions is highly variable, inviting all those institutions owning tertiary care centres to commence an entirely new NP course could prove damaging. Rather, the INC could, on a pilot basis, hand-pick institutions across the country that impart quality nursing education and try out the NP course in critical care. The programme could then be scaled up carefully to other institutions, on the basis of the evaluation of the feasibility, acceptance, outcomes and larger impact of the course.

- What will the career pathways of NPs be within and across professions? The career pathways for nurses in the country are poorly conceptualised, both within government and private health services. Also, hardly any thought is given to the inter-professional mobility of health workers, something that is increasingly finding mention in global human resource policy discussions (8).

- How are NPs to be institutionalised? Chalking out a formal system of licensing/registration and accreditation of NPs is important in institutionalising the services provided by the NPs in the health system. It is also equally important to have a strong legislation in place to protect the title of NPs. Legislation is a major determinant of the sustainability of the role of NPs. The countries which have NPs in their health system have a unique legislation to protect the title of NPs. It is also important to think of a mechanism for quality assurance that encompasses the oversight and accountability of NPs. At present, there is neither any legislation in place, nor has the existing Nursing Council Act, 1947 been amended to provide a legal basis for the title of NPs in India. Moreover, the mechanism for quality assurance for such a course on NP seems to be inadequate in the proposed curriculum. The INC mentions that students for this course will be selected on the basis of merit and an entrance examination; but who the entrance examination will be conducted by and how transparency will be ensured in the selection process have not been specified. The institutions wishing to start the NP course have been made accountable for the proposed programme. The INC asks the concerned/competent authorities from the institutions to sign an affidavit, assuming accountability for the programme and issuing standing orders to the NPs to practise in accordance with the INC standards. Whether the NPs will have to or not have to register in the state nursing councils and obtain a separate licence to practise is also not clear. The INC has prescribed minimum standards for institutions running the NP course; however, how often these institutions will be inspected is not known. Even though the course is expected to prepare graduate nurses to assume advanced roles such as those of clinical experts, managers, educators and consultants, the NC does not elaborate upon the career progression pathways of NPs. It is also not certain whether the NPs in critical care will be absorbed into the public health system, in which there is an acute shortage of specialist doctors. There are no guidelines on how the NPs will be compensated in a country where nurses (especially in the private health sector) are underpaid for the work they do.

Worse still is the fact that the discussions about specific health worker cadres are taking place in silos. For example, the draft National Medical Council Bill, which is currently under discussion, does not mention anything about nursing or any other professional council. This is despite the fact that the problems with the medical council that the Bill intends to tackle are larger problems of the regulatory bodies of all health work professions (9). We go on to present a case study of the implementation of the role of NPs in Australia and critically reflect upon its relevance to our settings.

Implementation of the role of NPs in Australia

The antecedents of and policy processes relating to the implementation of the role of NPs in Australia are well documented by the Australian College of NPs. The NP movement commenced in the late 1990s, spurred on by the perceived shortage of doctors and their reluctance to practise in underserved areas. The other factor was the desire of the nursing profession for increased autonomy and an expanded role. In addition, there was strong political support for the movement for independent practice by nurses. An independent NP task force was established in New South Wales to explore the feasibility of the role of NPs. In 1993, the task force released a discussion paper on issues related to the introduction of NPs. In 1994, a series of pilot projects on NPs were initiated. On the basis of the findings of these pilot projects, an NP reference group was established and an NP implementation policy was circulated. New South Wales was the first province in which the title of “NP” was conferred and protected by legislation (The Nurse Practitioners Act, 1998). Certain amendments were also made in other legislations, such as The Pharmacy Act,1964 and The Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act,1966, which have potential implications for the independent practice of nurses. Over a period of several years and after a similar process, the NP role was adopted in other jurisdictions, such as Victoria, Australian Capital Territory and Queensland. NPs were first introduced in rural health and later, in various specialities of hospital-based care, such as emergency care, geriatrics, mental health and primary care/community health. By 2001, NP sites were extended to metropolitan areas. Once the NPs’ roles had been established, measures were taken to determine their career pathways in 2006.

Putting nurses in the lead

The government also came up with nurse-led healthcare delivery models. One such initiative is the Walk-in Centre. This model of healthcare delivery provides treatment for minor ailments and injuries, and is led by a team of NPs and advance practice nurses. Walk-in Centres were seen as a convenient alternative to waiting in the emergency department. The NPs of Australia have their own professional body that aims at advancing the NP movement. The country’s health system currently has more than 1000 NPs. The Australian College of NPs has also developed educational material that targets healthcare consumers with a mind to informing them about the profession’s purpose. Competency and accreditation standards are in place for NPs and these are updated regularly on the basis of the healthcare needs of the population. The government acknowledges outstanding performances by NPs by conferring on them an award titled “NP of the Year”. Since 2010, medical reimbursement has been available for NP care in Australia (10).

The learning curve in the Australian case study

In Australia, the processes and structures (eg the Council of Australian Governments) within the government make it possible to adopt an evidence-based approach to public policy-making. It is also mandatory for policy-makers to submit a regulatory impact assessment for any policy proposal. In addition, the government explicitly endorses evidence-informed public policy-making in all sectors. The policy environment was also conducive to the design and implementation of polices concerning NPs (11). The development of the NP policy proceeded step by step and the policy was established in a systematic manner. This was possible because of the strong political will and the support of the government, which maintained a consistent stance throughout the NP movement. A lot of planning was done prior to the introduction of the NPs. The role of NPs was piloted to ascertain whether such a concept was feasible in the Australian health system. Various essential policy components were put in place for the implementation of the role of NPs (legislation, licensure, educational preparation, accreditation, etc.), thus preparing the ground for the NP. This ensured the sustainability of the role of NPs.

The scenario in India is very different from the Australian case. The lack of political support and the fragmented “band-aid” or fill-in-the-gaps approach towards using NPs are major deterrents to the establishment of responsive and sustainable healthcare systems. The movement to introduce NPs in the Australian health system was steered by the nurses and backed by strong political will, whereas nurses in India are still struggling. Considering the current scenario, one wonders if the Indian nursing community would come together for a collective negotiation to seek greater professional autonomy and steer a movement to extend its roles in the health system.

Nursing education in India

Before we venture into the debate on the relevance of independent NPs in India, we need to first examine the ways we prepare nursing professionals.

Adequacy

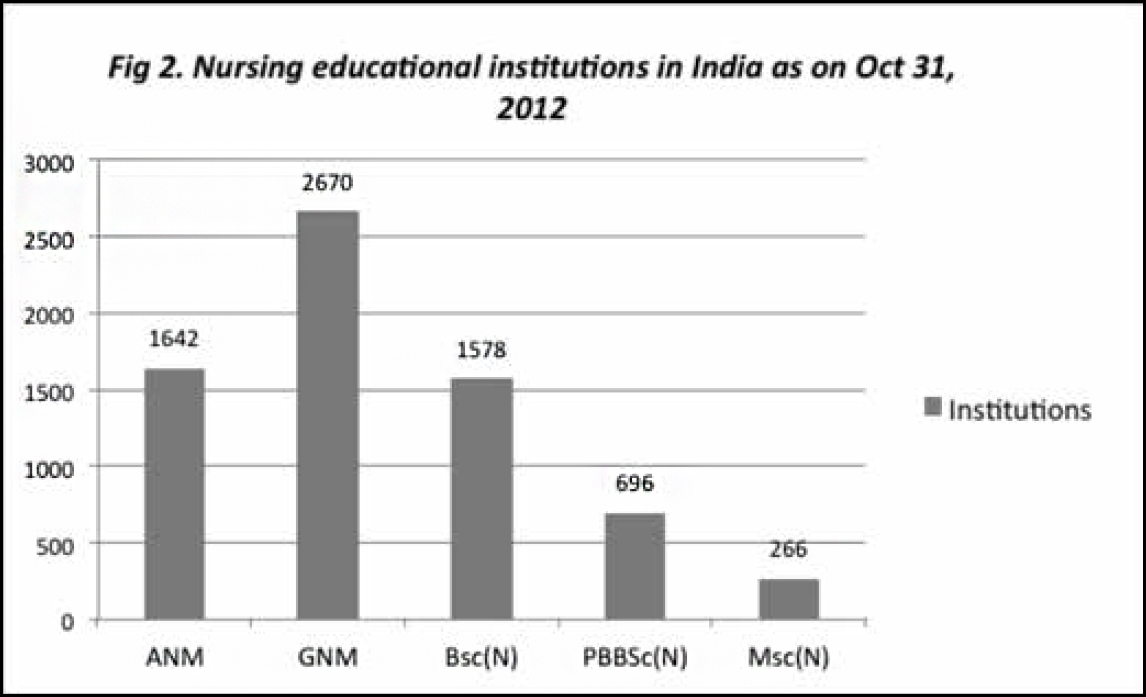

According to INC data (not updated since 2012), every year over 46,000 auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs), more than 100,000 nurses with a diploma degree, more than 100,000 nurses with a graduate degree, and over 3000 postgraduate nurses graduate from nursing educational institutions (7). Nursing educational institutions are mushrooming, yet India faces a phenomenal shortage of qualified nurses, to the tune of 2.4 million (12).

Quality

A robust health system requires a competent health workforce. The competence of the health workforce depends, to a large extent, on the quality of the education and training they receive during their preparation. Nurses accounted for 30.5% of the total health workforce in the country (13). The quality of the nursing education imparted in India is variable. Various studies and reports have highlighted significant gaps in the nursing curriculum and also, the failure of the INC to fulfil its mandate to assure quality in nursing education (5).

Under-regulation

Nursing education could be better regulated by addressing a few issues that have been identified. These are the high cost of nursing education in the private sector and the corrupt practices used by nursing educational institutions to get a licence to run nursing programmes. A government report found that more than 61% of nursing educational institutions are substandard, but continue to get licences from the state nursing councils and the INC by bribing the inspectors, exerting political pressure and indulging in other unethical practices (14). The other issues affecting the nursing education sector are the prevalence of academic dishonesty among nursing students, poor quality of nurse educators, redundant nature of a few aspects of the nursing curriculum, and a growing divide between theory and practice. This grim situation calls for the establishment of a robust governance structure in nursing education. Unless the inherent structural deformities in the basic training of budding nursing professionals are rectified, following the West and foisting NPs on the Indian health system will do more harm than good. Some substandard nursing educational institutions will be likely to view the NP course as another money-making opportunity.

When only the doctor leads…

The doctor-oriented health system poses a big obstacle to the progress of the nursing profession. Many examples can be cited in this regard. There is little, and sometimes no, space for nurses to influence health policies. All powerful administrative positions in the healthcare delivery system at the Central and state levels are occupied by clinicians, despite the availability of competent administrators in nursing. There continue to be disparities in the pay of Indian nurses and many are migrating to other countries because of economic factors. Dissatisfaction with working conditions, unhappiness with social attitudes towards nursing, and scant opportunities for career advancement are the other factors that contribute to the migration of nurses. This brain drain is costly as the competent nurses who leave are critical for fulfilling the national health goals (15).

Healthcare is provided by a team of qualified professionals and not just by physicians – a fact that is often forgotten. Any attempt to give wings to nurses and enable them to advance is aborted by the medical lobby. For example, in the recent past, the Indian Medical Association (formed by the community of practising physicians) vehemently opposed a Bill which proposed that even trained nurses should be allowed to perform medical termination of pregnancy. Because of the strong medical lobby, the Bill was not passed in Parliament (16). In countries such as Ethiopia and Bangladesh, nurses and other mid-level health workers are legally permitted to provide safe abortion services. In Ethiopia, mid-level health workers perform 82% of the abortion services (manual vacuum aspiration, post-abortion contraception) based in public and private facilities. Global analysis suggests that the quality of abortion services rendered by mid-level providers is of an equally high level as that of the services provided by physicians. Building the capacity of mid-level health workers such as nurses is certainly a wise investment of resources (17).

Time to address health workforce inequities

There has always been a politics of power play within and outside nursing that hinders the progress of the profession. To alter the power equations, therefore, one must carefully examine and diagnose the extent, location and type of power in the health system and in the larger sociopolitical context. This is vital to address the larger issues that ail the health system. The societal necessity to address health inequities makes healthcare as much a sociopolitical enterprise as a medical one. Researchers, policy-makers and health activists have adopted various strategies to study the inequities in the health system and reduce their effect on the population. However, there have been fewer attempts to study the inequities among healthcare providers. The community of doctors usually belongs to the more privileged sections of society, while nurses and allied health professionals belong to various socioeconomic strata. Moreover, nursing is one of the few female-dominated professions. Devaluing the work done by nurses and paying them lower compensation is a reflection of the status of women in our society (18). These elements, ie socioeconomic status and gender, could be among the reasons why nurses do not have much authority or say in the health system.

The prime focus of the health system and healthcare providers should be to ensure health for all. However, due to the constant struggle for power within the health system, among healthcare providers and in the larger society, “health” takes a back seat. The debate is more about who is the legitimate provider of healthcare, rather than what should be done to ensure health for all.

Contextualising the NP in India

It is in this context that the idea of the NP has emerged. The national-level consultation on NPs held by the MoHFW in the recent past concluded by emphasising that the NP curriculum designed by the INC should in no way infringe upon the Indian Medical Act, and that NPs should work under predetermined treatment protocols/guidelines. That NPs should work according to protocols/guidelines is not problematic; perhaps it will ensure uniformity in the standards of care provided across the country. What is disturbing is the dominance of the interests of medical professionals in the processes and the design of the protocols/guidelines. It gives them leeway to limit the scope of practice of the NPs. There is no universal definition of independent nurse practice. However, upon reviewing the literature, it was found that NPs are different from regular professional nurses in that they have more autonomy to practise, and the expertise and competencies required both for nursing and medical care of individuals, families and communities. The curriculum of the programme introduced recently by the INC on NP in critical care does not seem to be very different from that of the existing postgraduate (PG) courses in medical surgical and critical care nursing. The main difference is that unlike the latter, the former has adopted a competency-based training approach and includes extensive clinical training, with a few hours of classroom teaching. There is a need to evaluate whether this kind of learning approach can empower nurses to be a part of a healthcare team that contributes actively to clinical decision-making. At the most simple level, will it bring about any positive change in the present situation, in which nurses are viewed as caregivers who are meant to execute doctors’ orders, with no right to question them?

Further, the career opportunities available to those who complete the NP course in critical care are not so different from those available to postgraduate nurses. Ultimately, the role of the NP, as understood by the INC and the Government of India, seems to be “a nurse with additional training to follow the standing orders designed by doctors for some ailments”. This indicates that nurses are likely to remain in the clutches of the medical profession, and autonomy to practise will continue to be just an aspiration for competent nurses. The confusion about the role of NPs may obstruct their progress and deprive us of their potential contribution to service delivery.

The environment in which nurses practise is disheartening. However, there are a few redeeming factors, such as the emphasis laid by health system researchers, health activists and, at times, health policy-makers on the need to strategically position nurses in the health system so as to achieve better health outcomes. The need is to keep up the momentum and pave the way for positive policy directions concerning the nursing profession.

Early experiences with NP

The West Bengal government, in collaboration with Jhpiego, a non-profit international organisation affiliated to Johns Hopkins University, worked intensively to introduce NPs in midwifery into the health system by providing additional training to diploma and graduate nurses in public service (20). According to a research study, these nurses were placed in community health centres following the training sessions. Despite the fact that their performance was satisfactory, the West Bengal government could not create a unique cadre of NPs in midwifery owing to financial and structural issues (21). On the basis of the experience of West Bengal, Gujarat, too, initiated a course on midwifery in 2009. Three batches of nurses underwent the special training, and then rejoined the institutions in which they had been working earlier. “These specialised nurses are still working as staff nurses and waiting to get posted as nurse practitioners in midwifery, despite the sanctioning of 25 posts of midwives in the public hospitals (22). “Reputed institutions, such as Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore, have nurses who perform extended roles, including stoma nurses, family NPs, and diabetes nurse educators, but again, they are trained in-house and their titles are not protected by any legislation.

Global experience shows that legislation has been crucial to the sustenance and visibility of the role of the NP. This role has to be carved out in accordance with the context and the demands of healthcare consumers. In countries where the NPs’ role is implemented successfully, the aspects of the educational preparation of NPs/advanced practice nurses are enunciated clearly and there is legislation to confer and protect the title of “NP”. Further, there is a formal system of licensure, registration, certification and credentialing. NPs are given adequate scope to practise, especially when it comes to shaping the process of care for patients, eg prescribing medication/treatment, referring clients or providing inpatient care. They are also recognised as a legitimate point of contact for clients, have their own case load, provide preventive, promotive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative care, consistent with their area of expertise, and practise in a wide array of healthcare disciplines (23).

Pressing need for strong stewardship

There is a dearth of invigorating nursing stewards to take up issues that have an impact on the environments in which nurses practise. The prevalence of corrupt practices in nursing educational institutions reflects the loopholes in the regulatory processes adopted by the INC. There are several professional organisations for nurses in the country. These professional bodies can be broadly classified into two categories, based on the focus of their activities. First, there are those which conduct continuing education activities for nurses and thus, contribute to professional development. These are the Society for Community Health Nurses in India, Indian Society of Psychiatric Nurses, Society of Midwives of India and Nursing Research Society of India, to name a few. The second category of professional bodies, eg The Delhi Nurses Association, The Maharashtra Government Nurses Federation, Rajakiya Nurses Sangh in Uttar Pradesh, All India Government Nurses Federation, and United Nations Association, advocate for better working conditions and the economic welfare of nurses. There have been instances of nurses joining labour/trade unions and resorting to strikes and demonstrations to draw the government’s attention to their demands (24). The Trained Nurses Association of India (TNAI) has a relatively wide membership and has a presence across the nation. It is the oldest among the professional bodies for nursing in the country and is perceived of as a platform for nurses to voice their opinions. However, the TNAI has expressed its inability to act as the nurses’ legal representative in negotiations with the government, even at the local level, citing various reasons. Along with other professional bodies, the TNAI had filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court, highlighting the exploitation of nurses in the private health sector. The Supreme Court directed the Central and state governments to make laws to increase the pay and improve the working conditions of nurses in the private sector. This illustrates that the professional associations have taken a few halting steps to usher in reforms in the nursing profession (25). It is essential to build the capacity of these associations further and restore the credibility of the INC, given the gravity of the problems faced by nursing professionals.

The government is keen to introduce reforms in the sphere of doctors’ education. To this end, it has been proposed that the National Medical Commission (NMC) will replace the existing Medical Council of India. This is an opportune time for the government to baptise the NMC the National Health Commission and expand its scope to the regulation of nursing and allied health courses. This would be appropriate because the issues distorting medical education are not so different from those distorting the nursing education system. Moreover, nurses and midwives outnumber physicians, so any reforms that have an impact on the nursing sector will significantly change the health outcomes of the population.

It is important for the healthcare community to be open to and accept nurse-led models of the delivery of care, not for the sake of nursing but to achieve the goals of the overall health system. The provision of basic nursing education of a high quality will automatically pave the way for expanding the role of nurses in the health system. The first step in initiating independent nurse practice is to acknowledge that our nurses have the requisite capacity and then to strive for progressive changes. It would also be useful to consider the factors that have influenced the successful implementation of independent nurse practice in other countries and adapt the lessons learnt to the Indian context.

Funding support: None

Competing interests: The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

References

- Horrocks S, Anderson E, Salisbury C. Systematic review of whether nurse practitioners working in primary care can provide equivalent care to doctors. BMJ [Internet] 2002 [cited 2017 Mar 11]; 324:819. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7341.819. (Published 06 April 2002). Available from: http://www.bmj.com/content/324/7341/819

- Martínez-González NA, Rosemann T, Djalali S, Huber-Geismann F, Tandjung R. Task-shifting from physicians to nurses in primary care and its impact on resource utilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Care Res Rev. [Internet] 2015 Aug [cited 2017 Mar 11]; 72(4):395-418. doi: 10.1177/1077558715586297. Epub 2015 May 12. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25972383

- Shuler P, Davis J. The Schuler nurse practitioner practice model: a theoretical framework for NP clinicians, education and researchers. Journal of American Academy of Nurse Practitioners [Internet]. 1993;5(1) [cited 2017 Mar 11]. Retrieved from http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/documents/CAPNAH/files/Shuler%20Article.pdf

- Affara F. ICN framework of competencies for the nurse specialist. ICN regulation series; 2009 [cited 2017 Mar 11]. Available from: https://www.google.co.in/?gfe_rd=cr&ei=U57jV8q-FeiK8QfAuaPwDg#q=icn+framework+competencies+nurse+specialist

- Vollman RA, Misener RM. A conceptual model for nurse practitioner practice. Canadian Nurse Practitioner initiative, December; 2005 [cited 2017 Mar 11]. Available from: https://cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/pagecontent/pdf-en/05_practicefw_appendixa.pdf?la=en

- De Geest S, Moons P, Callens B, Gut C, Lindpaintner L, Spirig R. Introducing advanced practice nurses/nurse practitioners in health care systems: a framework for reflection and analysis. Swiss Med Wkly [Internet] 2008 Nov 1 [cited 2017 Mar 11]; 138(43-44):621-8. doi: 2008/43/smw-12293. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19005867

- Indian Nursing Council. Inviting application for nurse practitioner in critical care residency programme [cited 2017 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.indiannursingcouncil.org/

- Flexner A. Medical education in the United States and Canada. Bulletin Number Four; 1910 [cited 2017 Mar 11]. Available from: http://archive.carnegiefoundation.org/pdfs/elibrary/Carnegie_Flexner_Report.pdf

- Rao N. A national health commission would serve India better than a medical commission. The Wire [Internet] 2017 [cited 2017 Mar 11]. Available from: https://thewire.in/99213/health-commission-bill/

- Australian College of Nurse Practitioners (ACNP). Australian College of Nurse Practitioner history. Nurse Practitioner Movement in Australia [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 11]. Available from: https://acnp.org.au/history

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Government capacity to assure high-quality regulation in Australia. OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform; 2010 [online] [cited 2017 Mar 11]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/australia/44529857.pdf

- Roy S. Where have all nurses gone. Business Standard. 2015 [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.business-standard.com/article/opinion/subir-roy-where-have-all-the-nursesgone-115110301549_1.htm

- Anand S, Fan V. The health workforce in India. World Health Organisation [Internet]; 2016 [cited 2017 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/16058health_workforce_India.pdf

- Bhaumik S. Can India end corruption in nurses’ training? BMJ. [Internet] 2013 Nov 18 [cited 2017 Mar 11]; 347:f6881. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6881. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/content/347/bmj.f6881

- Li H, Li J, Nie W. The benefits and caveats of international nurse migration. International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 2014 [cited 2017 Mar 11];1(3):314-17. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2014.07.006

- Sharma RK. IMA opposes government’s proposed amendments to the MTP Act. The Economic Times [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 11]; 2014. Available from: http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2014-11-06/news/55835712_1_indian-medical-association-ima-members-20-weeks

- Ipas. Expanding the role of providers in safe abortion care: a programmatic approach to meet the women’s needs. Ipas [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 11]; 2016. Available from: http://www.ipas.org/en/Resources/Ipas%20Publications/Expanding-roles-of-providers-in-safeabortion-care-A-programmatic-approach-to-meeting-womens-needs.aspx

- Rao M, Rao KD, Kumar AK, Chatterjee M, Sundararaman T. Human resources for health in India. Lancet [Internet]. 2011 Feb 12 [cited 2017 Mar 11]; 377(9765):587-98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61888-0. Epub 2011 Jan 10. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)61888-0/abstract

- Arora R, Nakazi E, Morgan R. Gender and health systems leadership: increasing women’s representation at the top. IHP [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 11]; 2016. Available from: http://www.internationalhealthpolicies.org/gender-health-system-leadership-increasing-womensrepresentation-at-the-top/

- Jhpiego. Towards a strengthened nursing cadre in India. Inspiring stories of success. Jhpiego (an affilliate of Johns Hopkins University) [Internet]; [cited 2017 Mar 11] 2016. Available from: https://www.jhpiego.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Addressing-Jhpiego-India-Human-Resources-2016.pdf?x96543

- Nandan D, Mavalankar D, Bagga R, Sharma B, Sharawat R. Assessment of nursing management capacity in West Bengal. National Institute of Health and Family Welfare [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 11]. Available from: http://nihfw.org/pdf/Nsg%20Study-Web/West%20Bengal%20Report.pdf

- Sharma B, Mavalankar D. Health policy processes in Gujarat: a case study of the policy for independent nurse practitioners in midwifery. Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 11]; August 2012. Available from: http://vslir.iima.ac.in:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11718/11385/2012-08-01.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Masso M, Thompson C. Nurse practitioners in NSW ‘gaining momentum’: rapid review of the nurse practitioner literature. Centre for Health Service Development, University of Wollongong [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 11]; 2014. Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/nursing/practice/Publications/nurse-practitioner-review.pdf

- Mahindrakar S. Why nurses go unheard in India – even when they strike. Scroll.in [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 11]; 2016. Available from: https://scroll.in/pulse/815812/why-nurses-go-unheard-in-india-even-whenthey-strike

- Trained Nurses Association of India. Policy statement – strikes. TNAI [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.tnaionline.org/news/Policy/37.html