ARTICLES

Compensation for trial-related injury: does simplicity compromise fairness?

Mala Ramanathan, P Sankara Sarma, Udaya S Mishra

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2012.080

Introduction

India’s regulatory framework for research ethics is two pronged. Schedule Y of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940, of the Government of India (1), lays down the requirements for undertaking clinical trials for drugs and medical devices in India; it also requires compliance with the ICMR’s Ethical guidelines for biomedical research on human participants(2) for such trials. Other health research may use the ICMR’s guidelines but this is not mandatory. The regulatory framework is operationalised through the offices of the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation. However, the mechanisms of monitoring drug trials using this framework have proved to be rather weak.

The government of India has been making a concerted effort to strengthen the regulatory framework for clinical trials following disclosures of deaths in clinical trials (3) and the Parliamentary review of the status of regulatory mechanisms (4). The recent draft guidance for determining the quantum of financial compensation to be paid in case of trial-related injury or death is a step in that direction (5). The guidance calls for the following criteria to be used for determining compensation: the participant’s i) age, ii) income and iii) health status, iv) the seriousness and severity of the disease of the participant at the time of recruitment into the trial, and v) the extent of disability caused by the research intervention. It suggests a mechanism of combining these criteria using an algebraic formula which is easy to apply.

While this set of criteria may be acceptable, we have concerns about the methodology recommended for computing the compensation. We illustrate this by computing the sums to be paid under various assumptions, and then discuss the ethical dilemmas involved.

Formulae for computing compensation

The guidance recommends the following formula for computing compensation for a trial-related death (C1):

C1=A x B(1-F/100)

In this formula, ‘A’ is 50% of the participant’s monthly income; this represents what the participant would be contributing to his/her dependents. If the monthly income is less than what it would be with the legal minimum wage, or if the participant does not have any monthly income, ‘A’ will consist of the legal minimum wage (calculated monthly).

‘B’ is a multiplier that is given and varies with the age of the research participant. In this case, age is taken as the age of the research participant at death or disability.

‘F’ is the seriousness or severity of the participant’s disease at the time of recruitment into the trial. The compensation for a participant with a disease is computed as a fraction of what would be due to a healthy individual; for a healthy individual it would be ‘A’ x ‘B’ alone.

‘F’ is to be determined on a scale of 0 to 100, where ‘0’ represents “no deviation from good health” and ‘100’ represents death. The study investigator is required to set the seriousness or severity to this scale, while ensuring that the most serious or severe condition is not set at more than 50%. This means that even for participants for whom death is imminent due to an underlying health condition, the seriousness will not exceed 50%.

To determine compensation for injuries (C2), the guidance suggests the application of a different formula:

C2=A x B(1-F/100) x D/100

Here, ‘A’ is 60% of the participant’s salary, representing the contribution for his/her dependents. ‘B’ varies with age, as it does in the formula for computing compensation for a participant’s death. ‘F’ is the seriousness or severity of the disease at the time of participation. As the formula estimates the compensation for injuries and not death, another variable, ‘D’, is included: the percentage of disability caused to the participant due to trial participation. It is not clear how this is to be determined, but perhaps this is left to the ethics committee.

Computing compensation for death and disability

We used this methodology to compute the different compensation amounts that would be given to an individual with a monthly income of Rs 20,000: who is injured or dies, at the age of 30 and at the age of 40, and with different degrees of disease severity at the time of enrolment – healthy, with type 2 diabetes (T2DM), and with end stage cancer (ESCa). For the purposes of this exercise, the health of the diabetic is discounted by 10%, and the health of the cancer patient discounted by 50%, when compared to a healthy person. Finally, we considered five adverse outcomes: death, and survival with 90%, 70%, 60% and 50% disability.

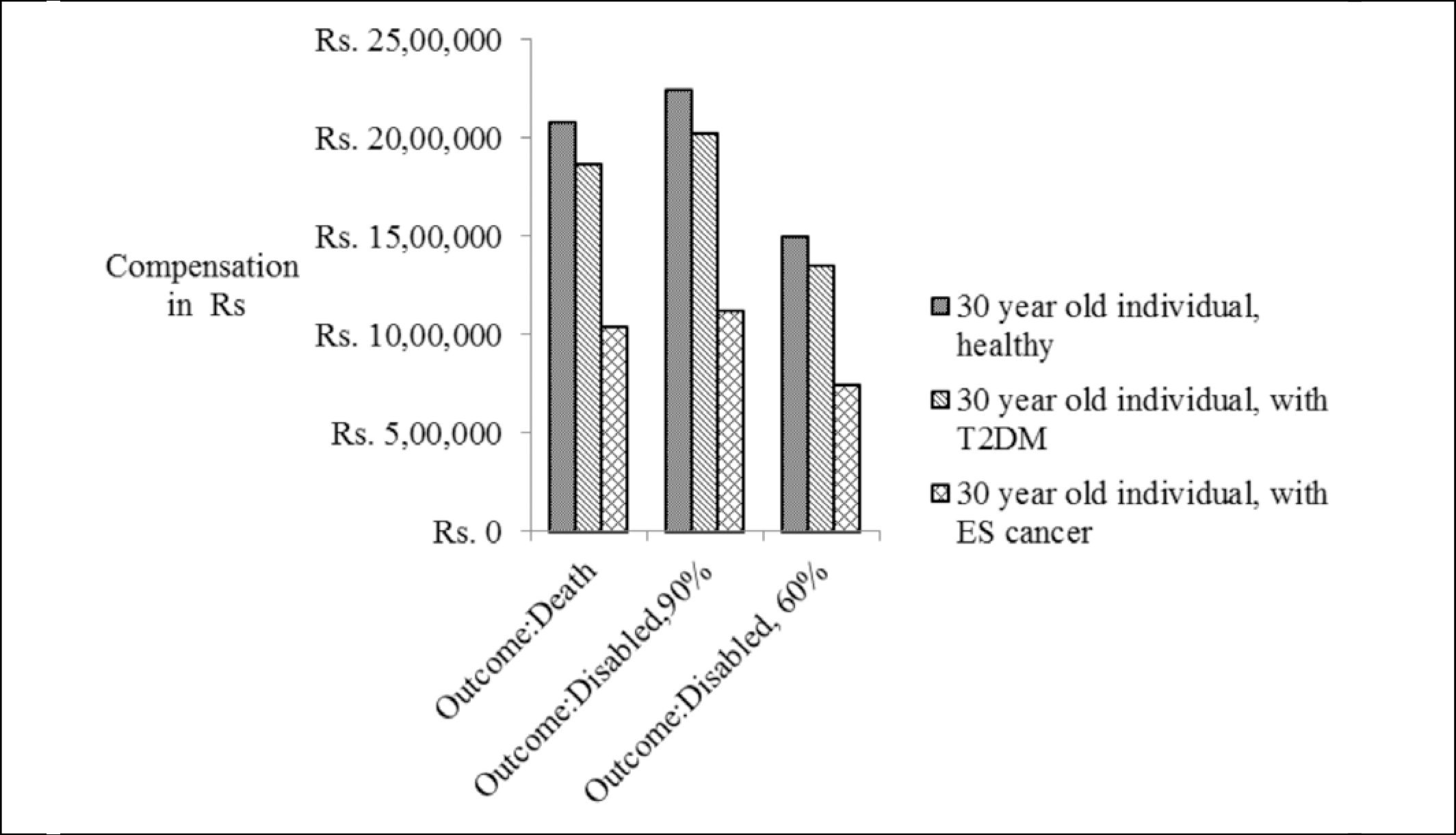

Figure 1 represents the result of this exercise for age 30 and for adverse outcomes death and survival with disability of 90%, 70% and 50%. Table 1 represents the results for two ages – 30 and 40. This will facilitate an understanding of the variation in compensation by age, health status at participation, and outcomes in terms of death and levels of disability. It can be seen from Figure 1 that at any specific age, the compensation for disability of 90% resulting from participation in clinical trials is higher than that for death. But for disability levels lower than 90%, the level of compensation declines to lower than the compensation for death. People living with disability must support themselves and their dependents. When a participant dies, the dependents alone need to be supported. Therefore it seems reasonable to argue that compensation for the disabled should be higher than that for the dead. But the current formula privileges death over disability except in the case of very severe disability. This is because of the manner in which the health status at the time of participation, and the extent of disability, are adjusted. This causes the compensation to increase when disability is around 90% and then decline very rapidly as the extent of disability reduces. The compensation due for a 70% disabled person becomes less than what is paid in the case of a dead person. The result is that participants who are alive but unable to carry on productive work may be better off dead in terms of the compensation received.

Figure 1: Variation in compensation by severity of disease at enrolment and outcome

Table 1: Compensation (in rupees) for death and varying disability outcomes due to participation in a clinical trial, for a person aged 30/40, earning Rs 20,000 per month and with varying underlying health conditions

| Age and health status at participation | For death | For outcomes with different levels of disability | |||

| 90% | 70% | 60% | 50% | ||

| 30 year old healthy | 20,79,800 | 22,46,184 | 17,47,032 | 14,97,456 | 12,47,880 |

| 30 year old T2DM | 18,71,820 | 20,21,566 | 15,72,329 | 13,47,710 | 11,23,092 |

| 30 year old ESCa | 10,39,900 | 11,23,092 | 8,73,516 | 7,48,728 | 6,23,940 |

| 40 year old healthy | 18,41,700 | 19,89,036 | 15,47,028 | 13,26,024 | 11,05,020 |

| 40 year old T2DM | 16,57,530 | 17,90,132 | 13,92,325 | 11,93,422 | 9,94,518 |

| 40 year old ESCa | 9,20,850 | 9,94,518 | 7,73,514 | 6,63,012 | 5,52,510 |

Ethical dilemmas in application

First, the draft document has borrowed the method for computing compensation from Schedule IV of the Workmen’s Compensation Act, 1923 (6).The Act specifies the method for computing compensation for a worker who has other entitlements such as healthcare under the Employees State Insurance Scheme, and is to be compensated for a death or injury in the workplace. The participant in a clinical trial is not a worker or employee under this Act, nor is the researcher an employer under this Act. On the other hand, even when research participants are remunerated for their participation, we assume that the option to not participate rests with them. Therefore the research participant is engaging in an altruistic activity, one that holds the promise of benefit to others, not to him/herself. We hold that any procedure that converts an altruistic act of participation in research to that of work, and reduces the fiduciary responsibility of the researcher to that of an employer, is morally repugnant and needs to be challenged by researchers and participants alike.

Second, the draft document suggests that compensation should be based on age and current income. We recognise the ethical rationale for these dispensations. Age helps determine the number of years that the participant might have lived had s/he not participated in the trial – assuming that nothing else would have gone wrong with his/her life barring this unfortunate event. The participant’s income or economic situation is used to determine the level of compensation; this is necessary to ensure that the risk of death or disability and the consequent potential for its compensation do not become an incentive to participate. However, it also treats participants who do not earn an income as earning the legal minimum wage. This will treat most women, children and other members of the community who work but are not employed in a job as minimum wage earners, and value them at a fraction of the value of an employed person. This is not a fair method of estimating the worth of a person.

Compensation is also dependent on two other criteria – seriousness and severity of the disease at the time of recruitment into the trial – that is, the health status at participation, and percentage of permanent disability. These criteria are relevant in the context of estimating compensation for death or disability. The life aspirations for a participant at the time of consenting to participate would be shaped by their life situation, and the disease affecting them would be part of their life situation. For estimating the seriousness and severity of the disease, – that is the health status at participation – the research investigator is required to use a scale of 0 to 100, with a caveat that it should not be more than 50. This also does not seem unfair on its own; the compensation for the death of a research participant who entered the trial terminally ill would be about half of what it would be for the death of a similarly situated healthy person.

The last criterion suggested for estimating compensation is percentage of permanent disability. However, the guidance does not specify how a percentage should be assigned to the disability caused by trial-related injury. In this context, a mere assessment of the disability level using the prescribed assessment scale under the People With Disabilities Act, 1995 (7) could be inadequate; this assessment would not take into account the extent to which the injury handicaps the person in their everyday functioning. For example, the loss of a portion of the right hand middle finger of a right-handed expert watch mechanic would not be the same as it would be for a left-handed bus driver, even though the social costs would be the same.

The guidance fixes the responsibility for making all these estimations on the ethics committee (EC) (8). In the normal course of events, this would be the same committee that cleared the trial. ECs in India have been found deficient in certain areas such as training of members and institutional support for functioning (9). There is also the chance that non-medical members in the committees are in ‘awe of the medical persons and speak little’ (10). However, in spite of these limitations, there are indications that some ECs are improving in their functioning (11). So the move to thrust the responsibility of calculating compensation on ECs can be welcomed, with caution, as it holds the potential for bringing in accountability.

There is another reason to welcome the move to give ECs responsibility of fixing compensation. The researcher can be expected to have a conflict of interest when determining whether the disability or death was caused by study participation. But a collective of peers, such as the EC, invested with the responsibility for weighing the risks and benefits of participation, is less likely tobe biased in determining compensation. Further, the fact that such a determination is called for itself represents the failure in the EC’s original assessment of risks and benefits. The very same EC therefore will be in a better position to determine the errors in its risk assessment and therefore judge the rationale for compensation better. Therefore, it is acceptable to give ECs the responsibility of determining compensation unless an alternative, unbiased mechanism is identified.

An alternative suggestion for estimating compensation

An attempt to mathematically compute the quantum of compensation has the potential to reduce a morally compelling act to one of administrative largesse, with attendant clerical rather than moral responsibility. It would be more advantageous and ethical to provide guidance to IECs on how to make this determination along the lines of what other countries have done (12) and leave the responsibility for determining the exact amount of compensation to them. The guidance could list the various criteria that need to be used and the rationale for these criteria, and the potential for trade-offs across criteria. Some possible criteria would be the extent of handicap in everyday social and professional life experienced by the participant as a result of the disability, the number of dependents and their characteristics, and so on. This would provide the flexibility required to manage the known criteria, and any others that may be recognised by the EC while undertaking this exercise. If such general guidance has served well in the determination of potential risks and benefits (which to this day have not been converted to an exact measurement of a net risk-benefit ratio), it would serve to determine a just compensation for a life lost or disabled. It has the potential to make ECs more meticulous in their engagement with research protocols. In the long run, one hopes that it would serve us to make death or disability due to clinical trial very rare for a participant.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Mr Ashwin Mishra, III Semester BPSc LLB (Hons.)Student, NLU, Jodhpur, for explanations regarding the legal aspects of worker compensations and Prof V Raman Kutty, AMCHSS, SCTIMST, for commenting on an earlier draft of this paper. This draft also benefited by discussions the first author had with Dr N Sreekumar, Associate Professor, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT, Madras, and Dr Nandakumaran Nair U, Visiting Professor, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Department, SCTIMST. Errors, if any, are our own.

References

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The Drugs and Cosmetics Act and Rules, The Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 and The Drugs and Cosmetics Rules, 1945 (as amended up to the 30th June, 2005) [Internet]. New Delhi: MOHFW, Government of India; 2005 [cited 2012 Sep 21]. 553p. Available from: http://cdsco.nic.in/Drugs&CosmeticAct.pdf

- Indian Council of Medical Research. Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research on Human Participants [Internet]. New Delhi: ICMR; 2006 [cited 2012 Aug 27]. 120p. Available from: http://icmr.nic.in/ethical_guidelines.pdf

- Press Information Bureau. Clinical trials [Internet]. New Delhi: MOHFW, Government of India;2010 Aug 6[cited 2012 Sep 21]. Available from: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=86675

- Department-related Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare. Fifty-ninth report on the functioning of the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) [Internet].New Delhi: Rajya Sabha Secretariat, Parliament of India; 2012 May 8[cited 2012 Sep 21]. 118p. Available from: http://164.100.47.5/newcommittee/reports/englishcomittees/committee%20on%20health%20and%20family% 20welfare/59.pdf

- Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO). Draft guidance, Guidelines for determining quantum of financial compensation to be paid in case of clinical trial related injury or death [Internet]. New Delhi: CDSCO;2012 Aug 3 [cited 2012 Sep 21]. Available from: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/compention.pdf

- Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India. Workmen’s Compensation Act 1923 (Amendment) Act 22 of 1984. Schedule IV. Factors for working out lump sum equivalent of compensation amount in case of permanent disablement and death [Internet]. New Delhi: Government of India;1983 [cited 2012 Sep 21]. Available from: http://lawmin.nic.in/legislative/textofcentralacts/1984.pdf

- Office of the Chief Commissioner for persons with disabilities. Guidelines for other disabilities [Internet]. New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. 2001 Jun 1 [cited 2012 Sep 21]. Available from: http://www.ccdisabilities.nic.in/page.php?s=reg&p=guide_others&t=yb

- The Gazette of India Extraordinary. Part II-Section 3-Sub-section (i). Regd.No.D.L.-33004/99. Published by Authority. No. 625.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (Department of Health) Notification [Internet]. New Delhi: MOHFW, Government of India; 2011 Nov 18 [cited 2012 Sep 21]. 13p. Available from: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/html/compensation_during_clinicaltrial.pdf

- Mathur R, Muthuswamy V. Survey of institutional thics committees in India – a preliminary report. In: Annual HRPP Conference; 2008 Nov 17-19; Orlando (Florida). Boston (MA): Public Responsibility in Medicine and Research; 2008 [cited 2012 Sep 21]. Available from: http://www.google.co.in/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCoQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.primr.org%2FWorkArea%2Flinkit.aspx%3FLinkIdentifier%3Did %26ItemID%3D6107&ei=1UlcUPWFJYGQrge6zYGQCg&usg=AFQjCNFC1TeGt94TOlBnCtO-Z3sJ8gBseQ

- Thomas G. Institutional ethics committees: critical gaps. Indian J Med Ethics. 2011 Oct-Dec; 8(4):200-1.

- Kadam R, Karandikar S. Ethics committees in India: facing the challenges! Perspect Clin Res [Internet]. 2012 Apr-Jun [cited 2012 Sep 12];3(2):50-6. Available from: http://www.picronline.org/

- Australian Government. Department of Health and Ageing.Therapeutic Goods Administration.Access to unapproved therapeutic goods.Clinical trials in Australia [Internet]. Woden ACT (Australia); TGA, Department of Health and Ageing: 2004 Oct [cited 2012 Sep 21]. Available from: http://www.tga.gov.au/industry/clinical-trials-guidelines.htm