COVID-19

Clinical ethics during the Covid-19 pandemic: Missing the trees for the forest

Vijayaprasad Gopichandran

Published online on April 30, 2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2020.053Abstract

The SARS-CoV2 pandemic has exposed the acute vulnerability of the health systems of countries worldwide. While countries are scrambling to contain the spread of the infection, the focus is largely on infection prevention strategies such as isolation, quarantine, physical distancing, hand hygiene, cough etiquette and country-wide lock-down. Important ethical concerns arise in the context of the public health interventions. However, while focusing on the forest, the population, attention must also be paid to the trees, the individuals who suffer the illness. This article focuses on the ethical conflicts between the largely public health- driven focus of the Covid19 prevention and containment measures versus patient-centred care for those who suffer the illness and the consequent moral distress of healthcare providers. The key argument is for countries to mainstream clinical ethics considerations for care of patients with Covid-19 as well as “non-Covid-19” illnesses.Keywords: SARS-CoV2, Covid 19, clinical ethics, duty to care, allocation of scarce resources, moral distress

Introduction

The novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV 2, has taken the world by storm (1). On the day this paper was written the virus had infected 2.2 million people worldwide and led to more than 1.53 lakh deaths (2). Many countries, including India, are seeing a surge in infections. In the past few months, the world has been jolted into understanding the importance of public health measures as never before in the recent past. Physical distancing, quarantine of international travellers and their contacts, isolation of people with infection, hand hygiene measures, cough etiquette and wearing of face masks have all been promoted aggressively (3). One of the most forceful and harsh methods of physical distancing adopted by several countries is the lockdown of all travel, work, social, educational and economic activities for protracted periods of time (4). On the one hand there is an argument that states must intervene with such stringent public health measures to save lives and protect their people. But on the other, the huge losses and suffering, especially of the poor and marginalised, due to the lockdown are overwhelming (5). The balance of individual liberties and rights versus the public good is very difficult to achieve in such situations.

Multiple clinical ethics issues have also emerged during this pandemic response. This is the phenomenon of “missing the trees for the forest”. In other words, so much attention is given to the macro-issues such as lock-down, physical distancing, isolation, quarantine, travel bans and other public health measures that their impact on the individual is neglected. This paper will focus on clinical ethics as it applies to two groups of people – people infected with the Covid-19 virus and people with “non-Covid-19” illnesses. It will attempt to draw out important ethical concerns and discuss the substantial moral distress that is faced by healthcare providers while handling these ethical conflicts. It will also argue that governments must set up and operate ethics consultations to help healthcare providers address the moral distress they will face.

Clinical ethics challenges arising in the care of Covid-19 patients

A number of ethical issues arise during the treatment of patients with Covid-19 (Table 1).

Treatment of Covid-19 patients as a means to an end

There is a fundamental difference of approach between clinical medicine and public health. While in clinical medicine the focus is on the individual patient, in public health it is on populations. Clinical medicine cares for individuals after the onset of illness and therefore lays emphasis on the alleviation of suffering, pain, psychological and emotional distress. On the other hand, public health works with healthy populations to prevent illness, or the spread of infection. In pandemics like Covid-19 there is a very fluid distinction between these two approaches. Public health and population protection take priority and all interventions by the state are directed towards containment of infection and reduction of morbidity and mortality. Most decisions are driven by statistics and mathematical modelling based on numbers of those susceptible, exposed, infected, or cured. Testing, detection, isolation, and treatment of individuals become a means to the greater end of keeping the numbers of infected persons low. The foundational tenets of clinical ethics including respect for the individual patient’s rights, values, preferences, care for individual needs, avoiding unnecessary harm to and discrimination against infected persons, all take a back seat during such emergency situations (6). Clinicians whose primary training is in caring for individual patients, are forced to adopt public health strategies during pandemics and this leads to moral distress.

Based on the experience of the author and other clinicians providing care for patients with Covid-19, it is observed that patients in isolation wards are often alone without any social or psychological support. In order to reduce the risk of infection to healthcare providers, they do not visit these patients frequently. Even when they go on rounds or to check on patients, they are all in full personal protective equipment, looking like faceless robots, with no warm smile to reassure them. In fact, many health facilities have actually deployed robots to dispense food and medicines for patients in isolation wards, thus removing even minimal human contact (7). Touch, which is one of the most valuable modes of communication in a healthcare provider-patient relationship is minimised to reduce transmission of infection. With curbing infection being the priority, many individuals are neglected and left to suffer alone and in silence. Hippocrates said, “Cure sometimes, treat often, comfort always.”. Covid-19 has made comforting the patient the least of the three priorities. Communication is one of the fundamental aspects of a good patient – provider- relationship and in clinical medicine, it is not just verbal communication but associated cues like touch, physical presence, body language, facial expression, which help patients feel reassured and comforted. This aspect of the patient – provider relationship suffers during admission in isolation wards. Unfortunately, infection control supersedes clinical care.

Working with uncertain evidence and unproven therapies

When a pandemic occurs due to a new infective agent, without any definitive treatment or drug, all clinicians clutch at straws to somehow save lives. This is the case with the SARS-CoV2 virus too. Hydroxychloroquine, in combination with Azithromycin, features in the treatment protocol for moderate to severe illness in India (8). Some state treatment protocols also include Oseltamivir, originally a drug against influenza virus, in the treatment of mild to moderate illness (9). Other anti-viral drugs such as Lopinavir/Ritonavir, originally an oral combination therapy against HIV, is also being studied in many contexts. Umifenovir is a repurposed anti-viral agent of interest as a therapeutic agent. Nitazoxanine, an antihelminthic agent, has also been proposed as a treatment. Remdesivir, a broad spectrum anti-viral agent with potent in vitro activity against SARS-CoV2 is said to be showing promising results (10). All these agents are still under clinical trial and none has so far been proven effective at the time of writing. Immunomodulatory agents such as Tocilizumab and Sarilumab are also under trial as agents to manage the “cytokine storm” that is associated with the Covid-19 illness. Treatment with convalescent plasma or hyperimmune immunoglobulin is being tried and reported to be successful (11). Such immunoglobulin therapy is going to be tried in India as well.

At present, other than supportive treatments and management of typical syndromes like acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septicaemia, multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), and cytokine storm, there is no established treatment. As some of these treatments feature in state recommended protocols, there is a risk that patients and the community may mistake these for definitive treatments. Besides, some of these drugs have serious adverse effects and may result in greater harm than good. One such example is the use of hydroxychloroquine among patients with severe illness. Often, such patients are of advanced age and have multiple comorbidities. This puts them at greater risk of cardiac arrhythmias, a known side effect of hydroxychloroquine (12). Working with such uncertain evidence can also lead to moral distress among the providers. In such pandemics, clinicians are left with no choice but to try experimental therapies on compassionate grounds. However, the level of uncertainty and the distress that it causes must be acknowledged and clinicians must be supported to overcome this distress. A trustworthy and transparent line of communication about the level of evidence and status of new therapies must be established.

Duty to care versus right to protection

One of the most contentious issues globally during this pandemic has been the scarcity of personal protective equipment (PPE) for healthcare personnel working with Covid-19 patients (13). They are directly exposed to high viral loads and therefore susceptible to more severe illness. Deaths of healthcare providers due to Covid-19 illness have been reported in large numbers in Italy, China, the United States and many other countries (14). There is a debate on whether healthcare providers have the duty to care when the health system does not protect their health and safety through adequate provision of PPE. In the UK, doctors and nurses appeared in a video, pleading with the government to improve the supply of PPE for their safety. This video was projected on to the walls of the Palace of Westminster (15). Doctors and nurses in Zimbabwe staged protests, and several resigned their jobs over lack of PPE (16). These examples highlight the global nature of the debate on duty to care versus right to protection.

Healthcare providers have multiple duties during such pandemic times, including the duty to care for their patients, the duty to protect themselves from getting infected so that they remain productive and in action throughout the period of the pandemic, the duty to protect their families and neighbourhoods, and to their colleagues, many of whom may become sick and have to go on leave, whose jobs they may have to cover, and finally a duty to society at large (17).

Nobody else can provide the unique and specialised services that healthcare providers can. They have spent years in learning these skills, and they must be put to maximum use during pandemics. There is a moral obligation based on a social contract between the healthcare provider and society that the provider will deliver healthcare services in time of need. While they have these duties to care, they also have the right to be protected from harm to themselves, because only then can they actually continue to serve society.

The General Medical Council (GMC) of the United Kingdom recommends that doctors must not refuse to treat patients because exposure will endanger their lives. Furthermore, the GMC recommends that striking the balance between serving during the time of need and protecting the health and welfare of healthcare providers must be ensured at the local level by providing adequate PPE to protect their health to the maximum extent possible (18). The American Medical Association adds that “physicians should balance the immediate benefit to the patients with their long-term ability to serve many patients” (19). The Code of Medical Ethics Regulations of the Medical Council of India, 2002, amended up to 2016, states that no physician can refuse to treat a patient during an emergency (20). There is no specific mention of the conundrum of duty to care versus protection of the self in the MCI code of medical ethics.

The emerging consensus across different international ethical guidance seems to be that duty to care during pandemics and emergency situations must be voluntary and must be associated with reciprocity from the health system, the government and society to protect providers. This can be in the form of provision of PPE, duty hours that offer adequate time for rest and recuperation, comfortable rooms to stay in while separated from family and loved ones, and adequate incentives in the form of monetary or non-monetary compensations. However, the fear, anxiety and guilt of transmitting the illness from patients to their loved ones is likely to cause substantial distress among healthcare providers and impact the care that they provide.

Rationing of scarce resources in pandemic situations

Though rationing of scarce resources is a public health concern, it has important implications for clinical care provision and clinical ethics. Many countries, including Italy and the United States, are facing a major resource crunch during the Covid-19 pandemic (13). Hospital beds, ventilators, medications, personal protective equipment for healthcare providers, are all becoming scarce resources. Clinicians are pushed into making morally contentious decisions on allocation of beds, ventilators and medicines. Making such decisions takes a heavy toll on the psyche of healthcare providers. Scarce resources are allocated based on ability to save most lives, ability to save most life years, priority to those who are likely to make significant contributions eg, healthcare providers, etc. These decision algorithms select a few patients in preference to others based on criteria such as age, presence of comorbidities, contribution to society etc, and having to make these decisions causes the clinician severe moral distress (21). Since these decisions have a significant impact on the community, active community engagement in order to understand community perspectives, values and priorities is important. Local guidelines must be developed to support healthcare providers in making rationing decisions that are relevant and acceptable to the community (22).

Dignity in death

Families of patients who die due to Covid-19 face serious emotional stress. Firstly, the patients die alone in the hospital isolation ward or the critical care unit. Their family and loved ones do not get a chance to say goodbye. The formalities of disposal of the body without contamination of the environment further place severe restrictions on certain important traditions and rituals that are performed as part of funeral rites. In a recent incident in Chennai, the cremation of the body of a doctor who died of Covid-19 infection was not allowed by the local community, for fear of contamination (23). This completely dehumanises the dead and strips the last shreds of their dignity. In some cases, patients die even before the test result for SARS-nCoV2 come out, and this leads to delays in disposal of the body. All of these are also major causes of ethical distress for providers.

Table 1: Ethical issues in the clinical care of patients with Covid-19

Clinical ethics considerations in the care of “non-Covid-19” patients

Clinical ethics challenges arise during a pandemic in relation to “non-Covid-19” patients, such as denial of clinical care for non-emergency conditions, and lack of clinical support for mental illness. In the rush to prepare hospitals and health facilities to receive the deluge of patients with Covid-19, many hospitals at the district and medical college levels have been converted into dedicated Covid hospitals. Here, basic clinical services which are considered “non-emergency” have been suspended by a government advisory (24). This is done for two main reasons ie hospitals are hot-beds of transmission of SARS-CoV2 and overcrowding in hospitals will make social distancing difficult to practise. In the current situation, most government health facilities have closed their non-emergency services and many private clinics and nursing homes have also been shut down in containment zones. Small, congested single-doctor clinics in many cities have also shut down because of the fear of community transmission of the disease (25). Reproductive and child health services, including antenatal care, delivery services, post-natal care and care of the new born child including immunisation is likely to suffer due to closure of several hospitals as well as redirection of grassroots health workers to Covid-19 containment activities. The worst hit during this situation are patients who have chronic non communicable diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiac diseases and chronic lung diseases. Many of these patients may not have an acute emergency. However, they will require long term medication, and have to face the effects of interruptions in their supply. Similarly, patients on long term drug treatment for tuberculosis and HIV are likely to suffer from shortages because of difficulties in reaching a health facility as well as supply chain problems. Patients on dialysis for chronic kidney disease, and those receiving treatment for cancer, also suffer due to access barriers and shut down of treatment facilities.

Prior experience from the Ebola pandemic of 2014-15 showed that deaths due to neglect of measles, malaria, HIV and tuberculosis were far more in number than Ebola deaths (26). The World Health Organisation released a document that outlined the key principles of maintaining essential health services during an outbreak situation (27). The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, followed by releasing a guidance on April 14 regarding maintaining essential health services through utilisation of non-Covid hospitals, empanelled private hospitals under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojna (PMJAY) – National Health Protection Scheme, telemedicine, home visits by frontline health workers and triaging patients in hospitals (28). (29) The operational feasibility of these guidelines and the way they are implemented on the ground needs to be observed closely.

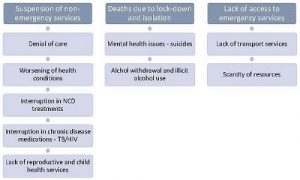

There are also reports of people suffering from mental health problems due to the prolonged lock-down as well as isolation and social distancing.(29) These individuals do not have access to care for their mental health problems. Another group of individuals badly hit by this pandemic are those dependent on alcohol. Several instances of people dying due to alcohol withdrawal have been reported, as all alcohol outlets were closed due to the lock down.(30) There have also been instances of individuals consuming toxic substitutes for alcohol such as paint varnish and shaving lotion which led to their deaths. These patients suffered due to lack of clinical alcohol deaddiction, detoxification support. Though emergency medical services are open and functional in many hospitals, patients find access to the emergency services difficult due to the lockdown. Further, interruptions in the supply chain lead to many hospitals facing drug shortages, so that even the quality of the limited services available in hospitals is poor. The various ethical issues in the care of “non-Covid-19” patients are described in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Ethical issues in clinical care of “non-Covid-19” patients

Moral distress of healthcare providers:

The Covid-19 pandemic has laid bare the gross under-preparedness of most health systems in the world in the face of a major, catastrophic health event. The healthcare providers, namely doctors, nurses, technicians and others are not in a situation to address these major ethical issues as described above. Some of these emerge from the conflict between their responsibility to the individual patient versus responsibility to the public during a public health crisis. Such ethical issues are a cause for severe moral distress among healthcare providers. In addition, health care providers face a serious dilemma as to whether they should turn whistle-blowers about the lack of PPE, lack of reasonable duty timings and suffering of vulnerable populations due to non-availability of non-Covid 19 services. They face probable punitive action that may extend to termination of service in some instances. The moral distress that healthcare providers are likely to face must be addressed (31). In addition to the numerous webinars on training healthcare providers to manage critical care of patients with Covid-19, infection prevention and control practices within the hospital and isolation ward settings, support must be offered through counselling to address moral distress arising while treating patients during pandemics. There are examples of a nurse in Italy and the finance minister of a German state who took their own lives probably because of the stress and irreconcilable moral distress arising from the pandemic (32,33). Support to healthcare providers to address moral conflicts can be offered as an ethics helpline within the hospital setting. The government must also focus on setting up Clinical Ethics Consultations, either on the telephone or through video conferencing for any healthcare provider or team faced with a moral conflict.

The most serious problems in clinical ethics during pandemic situations arise because of neglect of the trees while focusing on the forest. While prioritising prevention of the spread of infection, individual patients, their preferences, values and wellbeing are often neglected. This must be carefully weighed and considered while planning care during pandemic situations.

References

- Lai C-C, Shih T-P, Ko W-C, Tang H-J, Hsueh P-R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and corona virus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Mar;55(3):105924.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report – 84. Geneva: WHO; 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200413-sitrep-84-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=44f511ab_2

- Wilder-Smith A, Freedman DO. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020 Mar 13;27(2):taaa020.

- Lau H, Khosrawipour V, Kocbach P, Mikolajczyk A, Schubert J, Bania J, et al. The positive impact of lockdown in Wuhan on containing the COVID-19 outbreak in China. J Travel Med. 2020;

- Wang Z, Tang K. Combating COVID-19: health equity matters. Nat Med. 2020;1.

- Berlinger N, Wynia MK, Powell T, Hester M, Milliken A, Fabi R, et al. Ethical framework for health care institutions responding to novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Guidelines for institutional ethics services responding to COVID-19 Managing uncertainty, safeguarding communities, guiding practice [Internet]. New York; 2020 Mar 16[cited 2020 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.thehastingscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/HastingsCenterCovidFramework2020.pdf

- Yang G-Z, Nelson BJ, Murphy RR, Choset H, Christensen H, Collins SH, et al. Combating COVID-19—The role of robotics in managing public health and infectious diseases. Science Robotics. 2020 Mar 25;5(40):eabb5589 Available from: https://robotics.sciencemag.org/content/5/40/eabb5589

- Directorate General Of Health Services. Revised guidelines on clinical management of COVID – 19. New Delhi;DGHS; 2020 Mar 31[cited 2020 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/RevisedNationalClinicalManagementGuidelineforCOVID1931032020.pdf

- Department of Health and Family Welfare. Clinical Management Guidelines for Covid19. Chennai; DGFW;2020 Apr 4[cited 2020 Apr 25]. Available from: https://stopcorona.tn.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/TNSOP-6-1-version-1.3.pdf

- Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A review. JAMA. 2020 Apr 13; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6019

- Shen C, Wang Z, Zhao F, Yang Y, Li J, Yuan J, et al. Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. JAMA. 2020 Mar 27[cited 2020 Apr 25]. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2763983

- Hasan SS, Kow CS, Merchant H. Is it worth the wait? Should Chloroquine or Hydroxychloroquine be allowed for immediate use in CoViD-19? Br J Pharm. 2020 Mar 31[cited 2020 Apr 25];5(1):745. Available from: https://pure.hud.ac.uk/en/publications/is-it-worth-the-wait-should-chloroquine-or-hydroxychloroquine-be-

- Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical supply shortages—the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 25[cited 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2006141

- Adams JG, Walls RM. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA. 2020 Mar 12[cited 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2763136

- UK News. NHS staff make plea for PPE in video projected onto Palace of Westminster. Express and Star. 2020 Apr 17[cited 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.expressandstar.com/news/uk-news/2020/04/17/nhs-staff-make-plea-for-ppe-in-video-projected-onto-palace-of-westminster/

- Chingono N. Zimbabwe doctors and nurses down tools over lack of protective coronavirus gear. CNN. 2020 Mar 25[cited 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/25/africa/zimbabwe-doctors-nurses-ppe-strike/index.html

- Simonds AK, Sokol DK. Lives on the line? Ethics and practicalities of duty of care in pandemics and disasters. Eur Respir J. 2009 Aug;34(2):303–9.

- General Medical Council. Good Medical Practice. Pandemic Influenza: Responsibilities of Doctors in a National Pandemic. London; 2009[withdrawn 2012 Nov]. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/pandemic-influenza-2009—2012-55677705.pdf?la=en

- Morin K, Higginson D, Goldrich M. Physician obligation in disaster preparedness and response. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2006 Fall;15(4):417–31.

- Medical Council of India. Code of Medical Ethics Regulations. New Delhi: MCI;2002, amended up to 2016 Oct 8 [cited 2020 Apr 26] Available from: https://www.mciindia.org/CMS/rules-regulations/code-of-medical-ethics-regulations-2002

- Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 23[cited 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb2005114

- Biddison ELD, Faden RR, Gwon HS, Mareiniss DP, Regenberg AC, Schoch-Spana M, et al. Too many patients.A framework to guide statewide allocation of scarce mechanical ventilation during disasters. Chest. 2019;155(4):848–54.

- Express News Service. Nellore doctor’s cremation blocked by locals in Chennai. New Indian Express. 2020 Apr 14[cited 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: www.newindianexpress.com/states/andhra-pradesh/2020/apr/14/nellore-doctors-cremation-blocked-by-locals-in-chennai-2129895.amp

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Advisory for hospitals and medical education institutions. New Delhi: MoHFW;2020 [cited 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/AdvisoryforHospitalsandMedicalInstitutions.pdf

- Chitharanjan S. Small clinics shut down in Kozhikode due to Covid19 scare. The Times of India [Internet]. 2020 Apr 13[cited 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kozhikode/small-clinics-shutdown-in-kozhikode-due-to-covid-19-scare/articleshow/75119896.cms

- Elston JWT, Cartwright C, Ndumbi P, Wright J. The health impact of the 2014-15 Ebola outbreak. Public Health. 2017 Feb;143:60–70.

- World Health Organization. COVID-19: Operational guidance for maintaining essential health services during an outbreak. Geneva:WHO; 2020 Mar 25[cited 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/covid-19-operational-guidance-for-maintaining-essential-health-services-during-an-outbreak

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Enabling Delivery of Essential Health Services during the COVID 19 Outbreak: Guidance note. New Delhi: MoHFW; 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/EssentialservicesduringCOVID19updated0411201.pdf

- Goyal K, Chauhan P, Chhikara K, Gupta P, Singh MP. Fear of COVID 2019: First suicidal case in India! Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Feb 27;49:101989.

- Nidheesh M. In God’s own country, 1 died of Covid-19 but 7 commit suicide after alcohol ban. Livemint. 2020 Mar 29[cited 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.livemint.com/news/india/in-god-s-own-country-1-died-of-covid-19-but-7-commit-suicide-after-alcohol-ban-11585483376504.html

- Mazanec P. Covid 19 Resource: Ethical dilemmas facing nurses during the Coronavirus crisis: Addressing moral distress. Sigma CNE Course, Sigma repository; 2020 Mar 26[cited 2020 Apr 26] Available from: https://sigma.nursingrepository.org/handle/10755/20413

- Steinbuch Y. Italian nurse with coronavirus kills herself over fear of infecting others. New York Post. 2020 Mar 25[cited 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://nypost.com/2020/03/25/italian-nurse-with-coronavirus-kills-herself-amid-fears-of-infecting-others/

- Rahn W. German state finance minister Thomas Schäfer found dead. DW.com. 2020 Mar 29[cited 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.dw.com/en/german-state-finance-minister-thomas-schäfer-found-dead/a-52948976