COVID-19

Challenges for pregnant women seeking institutional care during the COVID-19 lockdown in India: A content analysis of online news reports

Surbhi Shrivastava, Saurabh Rai, M Sivakami

Published online first on January 18, 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2021.004Abstract

India’s nationwide lockdown to curtail the transmission of Covid-19 has given rise to concerns over the health system’s response to maternal and child health (MCH) services. This paper aims to understand the challenges faced by pregnant women seeking institutional care during the lockdown. We conducted a qualitative content analysis of 54 online news reports, published in English and Hindi, between 25 March 2020 and 31 May 2020. They covered cases across 17 states in India and 16 maternal deaths. Three broad thematic categories of challenges for pregnant women emerged from the analysis: 1) physical access to health facilities, 2) admission to health facilities, and 3) lack of respectful maternity care during the lockdown. In conclusion, strengthening health systems and incorporating MCH into the Covid-19 response is imperative. Failure to provide quality MCH services during the lockdown has implications for the continuum of women’s care, maternal mortality, and human rights.

Keywords: maternal health, Covid-19, content analysis, India

Introduction

Covid-19 is not the first coronavirus disease to afflict the modern world. Its predecessors include the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) of 2002–03 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) of 2012 (1). The response to Covid-19 was similar to previous public health emergencies in that human and financial resources were diverted from various health programmes towards measures to contain the pandemic (2). However, the global uptake of “physical distancing” measures makes it unique (3).

The Indian government imposed a nationwide lockdown as its primary strategy to contain Covid-19, which was first detected in the country on January 30, 2020 (4). With only four hours’ notice, the complete lockdown began on March 25, 2020 and was consecutively extended on April 14, May 3, and May 17 (5, 6, 7, 8). Enforced through authoritarian police action, the lockdown forced a population of over 1.3 billion to stay home (9). The move overlooked people’s need to step out and access health facilities for other major health concerns. Anticipating that this blinkered approach, which several countries adopted, would cause severe problems, the World Health Organization (WHO) urged world leaders to ensure the continuity of other health services and programmes, even when overwhelmed with the response to Covid-19 (10).

Globally, there have been concerns regarding the continued provision of maternal and child health (MCH) services during Covid-19 (11). History shows that outbreaks like these impact sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and MCH in various ways at the individual, societal, and systemic levels (12). The Ebola outbreak in 2014–15 created serious interruptions in the availability, uptake, outcomes, and demand for MCH services in Sierra Leone (13). It displayed the previously well-described “three delays” faced by pregnant women – in seeking care, reaching the facility, and receiving adequate treatment (14) – leading to an increase in maternal mortality.

In the case of India, upholding women’s access to quality maternal care at all times has ethical and human rights implications. India has made great efforts to incentivise institutional birth through the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) and Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK) (15). Therefore, a failure to provide care to women trying to access public facilities is a violation of state-recognised rights. Moreover, the increasing emphasis on respectful maternity care (RMC) in India (16) is a sign that disrespectful and abusive care during childbirth exemplifies maleficence and goes against accepted standards of medical ethics.

Unfortunately, India’s lockdown strategy did not include commensurate measures to ensure its health systems’ preparedness. The aftermath disproportionately affected vulnerable social groups, particularly pregnant women seeking institutional care. Media reports, the only available – albeit unverifiable ¬– source of information during the lockdown, covered some of the difficulties that pregnant women faced in various aspects of MCH (17, 18, 19). On April 14, 2020, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) released guidelines to enable the delivery of essential health services, emphasising that reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH) services are given particular attention while also ensuring the safety of healthcare providers (HCPs) (20). However, these guidelines were rarely implemented in the field (21, 22). Moreover, the lack of quality institutional care during the pandemic can be considered a violation of the government’s Labour Room Quality Improvement Initiative (LaQshya) to promote RMC (23). This underlines the urgent need to provide quality maternal health services, because even in “normal” times, India’s maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is high, at 113 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births (24); the discontinuity of services due to Covid-19 could lead to its escalation.

Although telephonic surveys on women’s health during the lockdown have been carried out in India (25), there has been no empirical research on the availability and quality of MCH. In the absence of such research evidence, a systematic analysis of alternative data sources may provide a glimpse of the ground reality. Against this backdrop, this paper aims to understand the challenges faced by pregnant women seeking institutional care during the Covid-19 lockdown in India through an inductive content analysis of online news reports.

Methods

Even though the government’s institutional birth utilisation data for April, May, and June 2020 were released in August 2020 after delays (26), the current Covid-19 pandemic makes primary data collection difficult. Therefore, we conducted a qualitative, descriptive content analysis (27) using online news articles from India, which could potentially lead to a conceptual map or a model (28). The news articles included primarily those published in English and Hindi between March 25, 2020 (when the total lockdown began) and May 31, 2020 (when it was relaxed). These sources reported on the challenges that pregnant women faced when seeking institutional care during the lockdown. While the lockdown serves as the period of analysis due to its unprecedented nature, we aim to describe all our findings from this period, and not just those that were unique or exacerbated underlying issues.

The search engines used were Google, Yahoo, and Bing. We used keywords such as “pregnant woman” and “pregnant woman denied care” to browse English news articles and “garbhavati mahila” (pregnant woman) and “prasav” (birth) for Hindi articles. We also added the names of each of the Indian states to the keyword search to identify supplemental articles in English. We first identified some articles through content shared in the authors’ social networks, which we then used to locate published versions for analysis. The inclusion criterion was reporting on the challenges faced by pregnant women who sought institutional care during the lockdown, including those who tried but failed to reach a facility. The exclusion criterion was reporting on the challenges of pregnant women in settings other than institutional care, notably migrant workers travelling long distances in the wake of the lockdown. Additionally, we excluded challenges for women who sought abortions and those who experienced miscarriages but did not seek institutional care. We conducted our last keyword search on May 31, 2020.

Our first search yielded 62 articles in English and 47 articles in Hindi. If multiple news articles reported the same incident, we chose the article which, irrespective of language, captured the incident most descriptively from the woman’s perspective. We included a total of 54 articles (31 in English and 23 in Hindi) sourced from 34 online news publications for the final analysis (details in Appendix I).

The first two authors, who are proficient in both languages, conducted a content analysis. This study followed the inductive approach. We analysed the manifest or surface-level content, which requires relatively objective coding without interpretation on the part of the coder (29), to plot state-wise news reports, the reported backgrounds of women, the number of deaths, and the context in which care was sought.

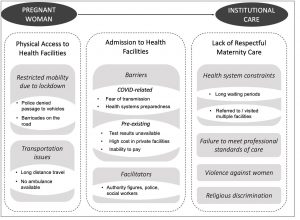

The first two authors read each article separately and extracted the relevant content. We translated the content from Hindi articles to English before our analysis. We removed the names of the pregnant women and their families, doctors, and hospitals to ensure confidentiality. However, we retained anonymous identifiers, such as religion, age, occupation, and type of hospital (government or private) to understand the context of the narrative. We open-coded and clubbed the excerpts to form categories and sub-categories through abstraction. As they emerged, we grouped these further into potential themes related to our topic. The findings evolved into a concept map of the major challenges that women experienced while seeking institutional care. The three broad thematic categories that emerged were physical access to health facilities; admission to health facilities; and lack of RMC during the lockdown.

Results

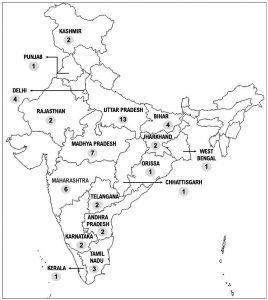

The articles that we analysed reported cases from 17 states in India (Figure 1). Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Madhya Pradesh (MP) topped the list in terms of the number of pregnant women denied quality institutional care, with 13 and 7 reported cases, respectively, whereas West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, Orissa, Punjab, and Kerala had one reported case each. Most news reports did not mention the backgrounds of the pregnant women. However, six articles described the women as “wife of a labourer”, “wife of a daily wage worker”, or “wife of a migrant”. Thirteen articles reported the challenges faced by Muslim women, whereas two reported on the experience of Covid-positive pregnant women.

Figure 1: State-wise number of online news reports on challenges faced by pregnant women seeking institutional care during the Covid-19 lockdown in India (N= 54)

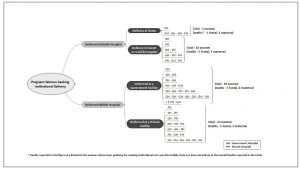

Figure 2 shows a pathway analysis of how women sought institutional care, the types of facilities they were referred to, and their eventual site of birth. From all the articles, we could determine clear pathways for 49 women. Seventeen women – more than one-third of the cases – either delivered at home, at the roadside, outside the hospital, or in transit (in an ambulance or other vehicle). Totally, 32 women delivered at a hospital (19 at government facilities and 13 at private facilities). However, only a third of them were provided care at the first facility they visited, whether government or private. Most women visited two or three hospitals before they were admitted, and some visited more than five facilities, going back and forth between government and private hospitals before finally being admitted. Overall, 27 articles reported deaths; of those, 16 were foetal deaths and 16 were maternal deaths.

Figure 2: Summary of pregnant women’s facility-wise pathways when seeking institutional care during the lockdown in India (N = 54)*

Physical access to health facilities

The unprecedented lockdown created hurdles for pregnant women starting from the first level of seeking institutional care – reaching a facility.

Restricted mobility due to lockdown

Several articles have reported that some women could not reach health facilities due to the nationwide lockdown. The police stopped and questioned them, even denying passage to ambulances carrying women in active labour. In the absence of police personnel (second quote below), barricaded roads impeded women’s transportation to health facilities. In such cases, women delivered in transit or even succumbed to death:

- The ambulance in which she was being taken to the *** hospital was stopped by the police for nearly 20 minutes on Tuesday. The police said the vehicle was entering a red zone in violation of the lockdown restrictions… As the woman’s relatives pleaded with the cops outside, her condition deteriorated, and she died of excessive bleeding in the ambulance. (Andhra Pradesh (AP), New Indian Express, May 20)

- The husband tried to rush her to a doctor on a scooter but there were barricades at every corner in the area blocking the roads due to the lockdown… He removed barricades from three places, but when he got down to remove another roadblock, his wife delivered on the road at around 2:30 am… one km away from the *** hospital. (AP, Times of India, April 17)

Women reportedly travelled 31–217 km to reach health facilities. While some managed to get ambulances to travel long distances, other women’s families had to arrange transport themselves because of the non-availability of ambulances. Due to the lockdown, some families could not even hire private vehicles.

- Her husband said that getting an ambulance or any vehicle was proving to be a task, so he took her to *** on his bike. (Maharashtra, Mumbai Mirror, 29 April)

- They travelled 31km to reach the facility. The doctor referred the woman to another hospital but there was no way for the family to go. So, the husband lay his wife down at a cycle stand outside the hospital. Some people helped him take her to the other hospital. (UP, Hindustan, 16 May)

Several news reports highlighted the problems faced by pregnant women in gaining timely admission to health facilities. Lockdown measures ensuing the Covid-19 outbreak raised fear all around and caused several routine services to close down. Some women were able to secure admission after interventions from people in positions of authority or access.

Covid-related barriers

Women who had not been tested for Covid-19, or whose test results were pending, were reportedly denied admission by health facilities out of fear of transmission. Women who showed any symptoms similar to Covid-19, or those coming from “high-risk zones” – areas with a large number of Covid-19 cases – were also denied admission. Further, the emergency night shift staff at hospitals were reassigned to other duties to address the gap in human resources caused by the pandemic.

- A pregnant woman who lives in a remote ‘red zone’ village in south Kashmir was denied admission to four hospitals and was forced to travel more than 100 km in the night before she could deliver her child. (Kashmir, The Wire, 5 May)

- Riding pillion on a motorbike, she and her husband struggled for nearly three hours to find a hospital… The local government primary health centre (PHC) was empty with its gates locked. Health officials claimed that all doctors at PHC were shifted for COVID-19 duty at nearby *** and there was no staff available for emergency night duty at PHC. Later, two private facilities too refused to attend her… Seeing the woman writhing in pain and her condition deteriorating, the policemen arranged for wooden benches and called an acquaintance nurse from her home and other women from the neighbourhood and asked them to safely deliver the baby there itself. (Punjab, Indian Express, 4 April)

Some facilities reportedly denied admission to Covid-positive pregnant women because they were not equipped to handle them. Meanwhile, others denied treatment to non-Covid women because the facilities were Covid-dedicated. Moreover, the staff at one facility were unclear if deliveries could be conducted during this period, as they had received no communication from higher officials. Such instances negatively impacted pregnant women:

- In the case of the 29-year-old, she approached 10 hospitals soon after she tested positive… But all south Mumbai hospitals refused admission, stating they do not have the facility to help infected women deliver. (Maharashtra, Indian Express, 22 April)

- The guard of the hospital stopped a pregnant woman at the gate and said that no one could enter the building without thermal screening, hence she had to wait. Within 15 minutes another woman in labour arrived at the facility but she was also refused admission. As both women waited, screaming in advanced labour, other women gathered around and used some cloth to create privacy and shielded the women while they gave birth. Around then, another pregnant woman arrived at the facility and she was also turned away. Her labour pains increased sharply. Hearing her screams, the women came running and helped her deliver too. (UP, Navbharat Times, 11 May)

Pre-existing barriers

Pregnant women were reportedly denied admission based on the non-availability of results of blood tests and ultrasound. Moreover, private facilities demanded exorbitant amounts and used the patients’ inability to pay as grounds for non-admission and denial of treatment.

- The hospital asked for blood tests and ultrasound before admitting the woman. Since these facilities were not available at the hospital, the woman’s family took her to a diagnostic centre and managed to get blood tests done by the afternoon. But the hospital refused to admit the woman without the ultrasound report. (UP, News18, 17 May)

- The hospital asked for Rs. 23,000 for [the] operation and Rs. 8,000 for [a] corona kit. When he expressed difficulty, they refused admission. (UP, Amar Ujala, 5 May)

- The hospital staff asked him for money. The husband deposited the Rs. 1000 he had at the time and told the staff he would go and arrange for the rest of the money. The money was not arranged in the next half an hour, so the woman was removed from the operation theatre and was left on the street outside the hospital.” (UP, Etoi News, 18 May)

A few reports mentioned that some pregnant women’s families approached people in positions of authority to have them admitted to facilities after the health staff had refused them. Some people reportedly used their political connections; others sought help from police officers and social workers. In some instances, family members or others informed higher officials within the bureaucracy of such cases of non-admission, and they intervened.

- Finally, I sought help from a social worker to get her admitted to ***… After much pleading and political pressure, the hospital agreed to admit her. But she was no more. (Maharashtra, Hindustan Times, 29 May)

- On Monday, the matter came to the notice of the District Collector, the Sub Divisional Magistrate and the Chief Medical and Health Officer. She was again admitted to the district hospital, but it was too late. Before reaching there, the foetus had died in the womb. (Chhattisgarh, Pioneer, 19 May)

- The woman, a resident of *** was admitted to the hospital after she complained of labour pain yesterday. After the medical staff realised that she had come from a COVID-19 buffer zone and her husband who had recently returned from another state and is in quarantine, they asked her family members to leave with the patient… Later, following the intervention of [an] MLA *** and [a] Zilla Parishad member, the woman was re-admitted to the hospital where she was kept in an isolation room. (Odisha, Odisha TV, 27 May)

The analysis of news reports revealed that pregnant women experienced poor quality of care during the lockdown due to various reasons. Some were related to systemic issues related to the health system while others pertained to the individual care provided by HCPs.

Health system constraintsArticles reported that on admission, women did not always receive RMC. They experienced long waiting periods which, in many cases, led to referral to another hospital or denial of admission. Several women reported having visited multiple facilities before being provided with any maternity care. Health staff asked family members to procure basic medical supplies like gloves before they treated pregnant women. Moreover, the staff did not communicate with the pregnant women and family members regarding their health issues.

- (The woman) approached *** PHC for delivery on April 24 but the PHC staff referred her to *** District Hospital. On reaching there, the doctors asked her to go to Kurnool in neighbouring Andhra Pradesh as her blood pressure was high and she was anaemic… an ambulance was arranged to shift her to *** District Hospital, about 100 km away. The doctors, after examining the woman at *** Hospital, found that her condition was critical and asked her husband to take her to *** Hospital in Hyderabad, another 100 km away. When the woman was shifted to XYZ Hospital, the doctors asked her to first undergo a COVID test as she was coming from a COVID hotspot. She was shifted to ABC Hospital, where she was tested for COVID-19. As the test report came negative, the next day she was shifted back to *** Hospital, where she delivered a baby boy. (Telangana, Outlook, 4 May 2)

- Around 11 pm, I was asked to bring a pair of surgical gloves before they could begin her treatment. Due to the lockdown and this being a late hour, I was not able to get the gloves even after searching for more than an hour. Denied any treatment at the hospital till 3 am, I took back my wife home. (UP, Times of India, 26 May)

Many facilities neglected post-birth complications, and, in some instances, the patients were discharged shortly after the birth.

- Around 6 hours after delivering, the woman experienced some discomfort after which the staff put her on a saline drip. She became unconscious and the family members requested the staff to refer her to the district hospital. The nurse who was on night duty told the family members that the doctor who will report for duty in the morning shift would do the referral. In the morning, the doctor referred her to the district hospital without even a check-up to ascertain the seriousness of the case. On reaching the district hospital the doctor there declared her dead. She had [had] low haemoglobin and the post-delivery bleeding proved to be fatal. (MP, Dainik Bhaskar, 15 May)

- The doctor suspected that she had symptoms of corona and so admitted her to the isolation ward, and she delivered there in a few hours. After that, no gynaecologist came to examine her, over three days. Her sample for COVID-19 test was sent to another hospital but the results were not sent even after three days. Her child had not received the Hepatitis B vaccine even two days after birth. (MP, Dainik Bhaskar, May 18)

Two reports described physical assault, verbal abuse, and sexual violence by HCPs.

- The woman was bleeding when she reached the government hospital. A female hospital staff, on seeing the blood on the floor, started hurling abuses at her based on her religion, forced her to clean the blood from the floor and thrashed her with slippers. The brother of the pregnant woman intervened and stopped her, and they left the facility. (Jharkhand, Janta ka Reporter, April 20)

- The woman informed her mother-in-law that during her stay in the isolation ward, one of the health workers sexually assaulted her for two days due to which she experienced excessive bleeding and had a miscarriage. When she told the security guard about the incident, he told her to think about her family’s reputation. Three days after returning from the isolation ward, the woman passed away. (Bihar, Tricity Today, 9 April)

Some articles reported that HCPs discriminated against pregnant Muslim women, denying them admission at the facility. HCPs also held the opinion that Muslim women were more likely to be Covid-19-positive, as they linked them to the Tablighi Jamaat event held in March at New Delhi, after which many Muslim men tested Covid-positive. This was their reason for denying care.

- The woman shared “The doctor told me that Muslims have connection with the Tablighi Jamaat, therefore, we cannot treat you here” … The doctor even refused to prescribe medicine to her and also treated other Muslim women in the same manner. (Delhi, Muslim Mirror, 23 April)

- The woman and her family pleaded with the doctor on duty but he along with other hospital workers flatly refused to treat the pregnant woman because she was Muslim. (UP, News18, 17 May)

Discussion

We analysed the content of online news reports to understand the challenges faced by pregnant women seeking institutional care during the Covid-19 lockdown in India. The concept map (see Figure 3) presents the three broad categories of challenges and their underlying issues. In the Indian context, the unavailability of ambulance services and staff at health facilities; long waiting periods; multiple referrals; failure to meet professional standards of care; and VAW are pre-existing issues (30) that also emerged in our study. However, other issues – such as restricted mobility due to the lockdown, fear of Covid-19 transmission, and the health systems’ lack of preparedness for a pandemic – emerged as additional challenges for pregnant women (11). Several documents show that routine healthcare is disrupted during such pandemics (11) as resources are diverted towards the emergency response, reducing access to care for other health issues (31). Thus, the additional issues posed by the pandemic exacerbate the existing challenges that pregnant women have to overcome when seeking institutional care.

Figure 3: Concept map of challenges faced by pregnant women seeking institutional care during the Covid-19 lockdown in India

The information around Covid-19 has led to the stigmatisation of possible carriers of the disease. Amidst the virtual epidemic of misinformation, there is immense fear and anxiety among people, which must be addressed through better communication (32). We found that though HCPs are better positioned to understand the scientific aspects of Covid-19, they also harbour these fears. The refusal to admit women hailing from red zones is reflective of their fear of transmission without proof of infection. Regardless, Covid-19 testing is not mandatory for pregnant women seeking institutional care, according to another MoHFW guidance note dated May 24, 2020 (33). Therefore, the state must amplify legitimate communication regarding Covid-19 and ensure that HCPs follow their guidelines so that the community complies with safety procedures and requirements.

The unreasonable implementation of the lockdown by the police impeded physical access to health facilities. This is also true of Kenya, where a pregnant woman died before reaching the health facility due to confusion over who was allowed to travel during the country’s dusk-to-dawn curfew (34). Contrary to the MoHFW guidelines, which allow the provision of MCH services, we found that ambulances were not available. Poor ambulance services, especially in rural areas, has been a long-standing concern (35); it persisted due to restrictions on public and private transport during the lockdown. Additionally, our pathways show that women had to visit multiple facilities – up to seven government hospitals or up to six private ones – to seek admission (see Figure 2). Most facilities, both government and private, denied them admission either due to fear of transmission or due to a lack of preparedness for the pandemic. Helplessness during the lockdown was not limited to pregnant women, and reports also speak about the plight of patients with other urgent health needs who have been unable to physically access health facilities during the lockdown in India (36, 37, 38).

The pandemic has disproportionately affected the poor and vulnerable population – from the absence of basic public health measures to loss of livelihoods (39, 40). As court orders mandate (21, 22), it is incumbent upon the state machinery to improve people’s access to public health. However, our paper reveals that when faced with challenges, women and their families had to approach people with privilege and authority to avail of institutional care. This is reflective of an omnipresent issue of inequitable access to healthcare, even outside of the pandemic. Moreover, while our observation that the HCPs demanded exorbitant amounts for treatment is not a new finding (41), the ability to pay must not be a determinant of access to health services for pregnant women. There is a need to regulate the private health sector so that it follows government advisories and acts as a resource for providing essential health services during Covid-19 (42).

Weak investment in the public healthcare system has posed a broader challenge to India’s Covid-19 containment plans (43), leading to inadequate and differential health systems preparedness at the state level (44). States like Kerala fared well, while other states grappled with their response strategies (45). Our findings shed light on infrastructural shortcomings in health facilities, which left HCPs underprepared to treat pregnant women while themselves staying safe from Covid-19. The shortage of staff due to Covid duties translated into long waiting periods at various facilities. Although these challenges are not unique to the pandemic, the contexts in which they manifest have exacerbated them. Researchers have predicted a long haul for this outbreak in India and have identified a huge requirement for infrastructure (46). Concerted efforts to strengthen India’s health systems through investment in public health infrastructure and human resources are the need of the hour.

This paper found that the treatment pregnant women reportedly received after admission to facilities during the Covid-19 lockdown did not align with RMC. Several facilities did not meet professional standards of care, neglecting and abandoning many women who sought treatment. Some women were reportedly subjected to physical, verbal, and sexual abuse. Such instances are not only detrimental to women’s health – they could also lead to death. This goes against the ethical principle of non-maleficence and violates women’s autonomy, particularly when they are in a vulnerable condition like pregnancy. Some reports also shed light on religious discrimination against pregnant Muslim women, which became an added impediment for them during the lockdown. We argue that discrimination on any grounds is antithetical to several aspects of the Hippocratic oath (47). The systemic failure of the health systems in ensuring access to health facilities for pregnant women, compounded by the HCPs’ non-adherence to professional ethical standards, resulted in several SRHR violations for women during the lockdown.

RMC and women’s health continuumIndia has an insidious problem of mistreatment of women during childbirth, also known as obstetric violence (48). Recognising this, the nation has started to emphasise the principles of RMC, as outlined by the Universal Rights of Childbearing Women charter (49) and the government’s LaQshya guidelines (23). Despite the need for and commitment to RMC, several facilities did not provide quality intrapartum care within a framework of accountability during the Covid-19 lockdown (50). The period of childbirth is crucial for pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality, both of which increased in association with the SARS and MERS outbreaks (51). We found media articles that reported the deaths of 16 pregnant women, and, in some cases, their foetuses, while they sought institutional care during the lockdown. Moreover, the facilities compromised on quality post-natal care by discharging women immediately after childbirth. This supplements pertinent concerns about both maternal and infant mortality, as Covid-19 is feared to have set back several years of progress in lowering the numbers of these basic health indicators (10, (52).

The continuum of care for RMNCH (53) is likely to be adversely affected during public health emergencies, as we can see in the case of Covid-19. The increased burden on health systems due to the coronavirus are likely to substantially reduce access to abortion and contraception (54). Some reports have flagged apprehensions about its impact on pregnant women’s mental health (55), many of whom experienced increased anxiety, became overwhelmingly distressed about the outbreak of Covid-19, and felt vulnerable owing to their pregnancies (56). Moreover, in accordance with proposed modifications to make the continuum of care more inclusive (57), there are major concerns regarding the potential rise in VAW due to restrictions imposed by the lockdown (58), leading some to call it a “shadow pandemic” (59). Therefore, the results of this study must not be seen in isolation, but as a symptom of the larger impending crises of SRHR and MCH, which could negatively impact women’s health outcomes for years to come. Women-centred public health strategies addressing their differential health needs in various settings should be paramount.

Limitations and strengths

This study has certain limitations. First, our proficiency in only English and Hindi restricted us from studying articles in other regional languages. We did not find any relevant news reports from the North East; Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Haryana in the North; or Gujarat and Goa in the West. Second, we have used news reports with the caveat that there may be limitations to the data, which we have not been able to verify. Not all articles reported the background details and contexts of the pregnant women. They also did not provide narratives about the women’s experience while they sought care. Thus, we could not conduct a deeper analysis on the intersection of various determinants of health and how they shaped women’s experience of seeking institutional care during the lockdown. Third, in some instances, multiple news sources reported the same incident, thus giving us some scope to verify the narrative across articles. However, there is no way of ascertaining the motivations behind the media coverage that we analysed in this study, and the results are not a representation of all reproductive care provided by HCPs during the pandemic in India

Despite these limitations, the strength of our study is that in the absence of robust data, it serves as a systematic inductive analysis that provides a picture of the challenges faced by pregnant women seeking institutional care during the Covid-19 lockdown in India. To the best of our knowledge, a similar study in this context has not yet been conducted. This paper can further the discourse of some pre-existing barriers that pregnant women have faced during the lockdown despite the presence of clear guidelines and schemes for safe and respectful institutional birth. Among the previously mentioned “three delays” (14), we describe the second and third delays clearly, outlining challenges in accessing the facility and obtaining prompt, adequate care. Future research can build on these ideas to develop a more robust empirical study that captures all the “three delays” that pregnant women face while seeking institutional care. Moreover, the scope of our analysis was limited to those seeking institutional birth, but future research can explore other important settings, such as migrant workers in transit, where pregnant women did not receive quality care during the pandemic.

Conclusion

In the months between the first Covid-19 case in India and the start of the lockdown lay a missed opportunity for planning concerted public health action. Even the time that the government bought through the lockdown did not see efforts towards inclusive policy decisions. On the contrary, the pandemic is deepening pre-existing inequalities and exposing vulnerabilities in social, political, and economic systems that are amplifying its impacts (60). This paper underscores the need for evidence-based, equitable policy action, during and post-pandemic.

Going forward, this study must be considered a much-needed wake-up call, highlighting the need for long-term changes to India’s health system (44). In sum, ensuring the preparedness of health systems for a pandemic, where facilities provide continuous institutional care and proper referral mechanisms to pregnant women – especially those from marginalised communities – is in line with the central tenets of universal health coverage. The existing guidelines and policies for pregnancy care, especially LaQshya, need better implementation, within and outside of the pandemic. Finally, the government’s legislature, executive, and judiciary must uphold human rights and ethical standards at all times to promote the health of vulnerable populations, especially during a pandemic.

AcknowledgementsWe sincerely value the feedback received from the reviewers which greatly helped us shape the paper. We are grateful to Mr Pravesh Verma for his assistance in locating some of the Hindi newspaper articles included in this study.

Conflict of interests and external funding: None declared

Ethics Committee approval: This research is an analysis of open-access online news reports.

Appendix I: Summary of all online news reports included in the analysis (N= 54)

| Date | Online Source | Reference |

| ENGLISH | ||

| 28 March 2020 | Deccan Herald | PTI. Border gates closed, Bihar woman delivers baby in ambulance in Kerala’s Kasaragod, Deccan Herald, 28 March 2020, https://www.deccanherald.com/national/border-gates-closed-bihar-woman-delivers-baby-in-ambulance-in-keralas-kasaragod-818561.html |

| 4 April 2020 | Indian Express | Goyal D. 3 hospitals turn couple away, two Punjab cops help woman deliver child on roadside. Indian Express, 4 April 2020, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/3-hospitals-turn-couple-away-two-punjab-cops-help-woman-deliver-child-on-roadside-6346600/ |

| 5 April 2020 | Free Press Journal | Pranvendra S. Rajasthan: Controversy erupts after pregnant Muslim woman allegedly denied treatment as baby dies in ambulance. Free Press Journal, 5 April 2020, https://www.freepressjournal.in/india/rajasthan-controversy-erupts-after-muslim-pregnant-woman-allegedly-denied-treatment-as-baby-dies-in-ambulance |

| 12 April 2020 | Mumbai Mirror | Mishra L. Pregnant women bear brunt of stressed healthcare system. Mumbai Mirror, 12 April 2020, https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/coronavirus/news/pregnant-women-bear-brunt-of-stressed-healthcare-system/articleshow/75101923.cms |

| 17 April 2020 | Times of India | Rao CS. In Hyderabad, woman delivers baby on the street amid lockdown. Times of India, 17 April 2020, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/hyderabad/baby-born-on-road-in-suryapet-as-dad-battles-barricades/articleshow/75191209.cms |

| 20 April 2020 | Janta Ka Reporter | JKR Staff. Muslim pregnant woman in Jharkhand ‘denied’ treatment, ‘blamed’ for coronavirus spread; loses child after being allegedly abused and assaulted. Janta Ka Reporter, 20 April 2020, http://www.jantakareporter.com/india/muslim-pregnant-woman-in-jharkhand-denied-treatment-blamed-for-coronavirus-spread-loses-child-after-being-allegedly-abused-and-assaulted/288200/ |

| 21 April 2020 | Hindustan Times | Giri P. Kalimpong’s only Covid-19 hit family triggers panic, discrimination in north Bengal hills. Hindustan Times, 21 April 2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/kalimpong-s-only-covid-19-hit-family-triggers-panic-discrimination-in-north-bengal-hills/story-LQ2aGfawtnjP7Bhbfw6peP.html |

| 22 April 2020 | Indian Express | Barnagarwala T. Amid dearth of maternity hospitals admitting Covid patients, two women give birth. Indian Express, 22 April 2020, https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mumbai/denied-hospitalisation-harrowing-time-for-pregnant-women-with-covid-6373288/ |

| 23 April 2020 | Muslim Mirror | Masoud AB. Take stringent action against Islamophobes: CPI(M). Muslim Mirror, 23 April 2020, http://muslimmirror.com/eng/take-stringent-action-aginst-islamophobes-cpim/ |

| 23 April 2020 | Telegraph | Choubey P. Probe into 2 deaths in coal town. Telegraph, 23 April 2020, https://www.telegraphindia.com/states/jharkhand/coronavirus-outbreak-in-jharkhand-probe-into-2-deaths-in-dhanbad/cid/1767239 |

| 28 April 2020 | Times of India | Natu N, Debroy S. Pregnant woman without coronavirus report turned away by Bandra hospitals. Times of India, 28 April 2020, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/pregnant-woman-without-coronavirus-report-turned-away-by-bandra-hospitals/articleshow/75418724.cms |

| 29 April 2020 | Mumbai Mirror | Ganapatye S. Midwife to the rescue as 4 hospitals turn down woman. Mumbai Mirror, 29 April 2020, https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/mumbai/other/midwife-to-the-rescue-as-4-hospitals-turn-down-woman/articleshow/75439497.cms |

| 1 May 2020 | New Indian Express | Express News Service. Pregnant woman suffers miscarriage after private hospital denies treatment in Tamil Nadu. New Indian Express, 1 May 2020, https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/tamil-nadu/2020/may/01/pregnant-woman-suffers-miscarriage-after-private-hospital-denies-treatment-in-tamil-nadu-2138032.html |

| 2 May 2020 | CNBC TV18 | Shukla A. Rural India and COVID-19: Pregnant women risk long travel in search of safe hospital. CNBC TV18.. 2020 May 2; Available from: https://www.cnbctv18.com/healthcare/rural-india-and-covid-19-pregnant-women-risk-long-travel-in-search-of-safe-hospital-5826661.htm |

| 3 May 2020 | Hindustan Times | Dutt A. With hospitals overwhelmed, pregnant women left with no care or place to give birth. Hindustan Times, 3 May 2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/delhi-news/with-hospitals-overwhelmed-pregnant-women-left-with-no-care-or-place-to-give-birth/story-iqOmJLgWn4TyXwx719O8vM.html |

| 3 May 2020 | Kashmir Monitor | Hassan F. Family on road with body on trolley: Another pregnant woman dies of delayed care in Anantnag. Kashmir Monitor, 3 May 2020, https://www.thekashmirmonitor.net/family-on-road-with-body-on-trolley-another-pregnant-woman-dies-of-delayed-care-in-anantnag/ |

| 4 May 2020 | Outlook | IANS. Telangana HC takes serious note of pregnant woman’s death. Outlook, 4 May 2020, https://www.outlookindia.com/newsscroll/telangana-hc-takes-serious-note-of-pregnant-womans-death/1823928 |

| 5 May 2020 | Wire | Ahmad M. Kashmir: In labour, Woman From ‘Red Zone’ Turned Away From 4 Hospitals. Wire, 5 May 2020, https://thewire.in/health/kashmir-covid-19-red-zone-pregnant-woman |

| 8 May 2020 | NewsClick | Bhattacharya D. women struggle to access maternity care in Delhi, Organisations write to govt. NewsClick. 8 May 2020; Available from: https://www.newsclick.in/COVID-19-Lockdown-India-Health-Access-Pregnant-Women |

| 11 May 2020 | Onmanorama | Onmanorama Staff. Turned away by 3 Bengaluru hospitals, Kerala woman delivers baby in auto-rickshaw. Onmanorama. 11 May 2020. Available from: https://www.onmanorama.com/news/kerala/2020/05/10/kannur-woman-delivers-baby-in-autorickshaw.html |

| 19 May 2020 | Pioneer | Staff Reporter. Pregnant woman loses fetus due to callousness. Pioneer, 19 May 2020, https://www.dailypioneer.com/2020/state-editions/pregnant-woman-loses-fetus-due-to-callousness.html |

| 20 May 2020 | New Indian Express | Express News Service. Police hurdle kills pregnant woman in Andhra Pradesh. New Indian Express, 20 May 2020. https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/andhra-pradesh/2020/may/20/police-hurdle-kills-pregnant-woman-in-andhra-pradesh-2145586.html |

| 22 May 2020 | News Minute | Bharati SP. A nine-month pregnant woman’s ordeal at a Chennai COVID-19 isolation ward. News Minute, 22 May 2020, https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/nine-month-pregnant-womans-ordeal-chennai-covid-19-isolation-ward-125108 |

| 24 May 2020 | Wire | Kumar S. This pregnant woman was denied treatment at a Buxar govt hospital – and she’s not alone. Wire, 24 May 2020, https://thewire.in/communalism/bihar-pregnant-woman-government-hospitals-treatment |

| 25 May 2020 | New Indian Express | Express News Service. Fearing COVID-19, pregnant woman refused treatment by doctors at two government hospitals in Andhra. New Indian Express, 25 May 2020, https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/andhra-pradesh/2020/may/25/fearing-covid-19-pregnant-woman-refused-treatment-by-doctors-at-two-government-hospitals-in-andhra-2147911.html |

| 25 May 2020 | Times Now News | Mirror Now Digital. Medical apathy in UP: Pregnant woman dies after private hospitals refuse to admit her. Times Now News, 25 May 2020, https://www.timesnownews.com/mirror-now/in-focus/article/medical-apathy-in-up-pregnant-woman-dies-after-private-hospitals-refuse-to-admit-her/596540 |

| 26 May 2020 | Hindu | Special Correspondent. Adambakkam police help pregnant woman. Hindu, 26 May 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/chennai/adambakkam-police-help-pregnant-woman/article31682122.ece |

| 26 May 2020 | Times of India | Lavania D. Agra: Pregnant woman in labour told at CHC to get gloves first. Times of India, 26 May 2020, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/agra/pregnant-woman-in-labour-told-at-chc-to-get-gloves-first-baby-dies/articleshow/75982865.cms |

| 28 May 2020 | New Indian Express | Express News Service. Denied entry to hospital, apartment for home quarantine, Dubai returnee in Mangaluru suffers miscarriage. New Indian Express, 28 May 2020, https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/karnataka/2020/may/28/denied-entry-to-hospital-apartment-for-home-quarantine-dubai-returnee-in-mangaluru-suffers-miscarriage-2149288.html |

| 29 May 2020 | Hindustan Times | Pol M. Pregnant woman dies in Mumbra after hospitals refuse to admit her. Hindustan Times, 29 May 2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/pregnant-woman-dies-in-mumbra-after-hospitals-refuse-to-admit-her/story-nKhKd40t4WNAnS8kkl4TPL.html |

| 27 May 2020 | Odisha TV | Mallick S. Coronavirus agony: Pregnant woman spends 11 hours on hospital verandah In Odisha. Odisha TV, 27 May 2020, https://odishatv.in/odisha-news/coronavirus-agony-pregnant-woman-spends-11-hours-on-hospital-verandah-in-odisha-453803 |

| HINDI | ||

| 7 April 2020 | Amar Ujala | Amar Ujala Bureau. Family circled hospitals, childbirth could not happen due to lockdown, pregnant woman’s breath stopped. Amar Ujala, 7 April 2020, https://www.amarujala.com/uttar-pradesh/bareilly/lock-down-family-members-circling-the-hospital-pregnant-s-breath-stopped-bareilly-news-bly4018806195 |

| 9 April 2020 | Tricity Today | Tricity Reporter. Health worker molests pregnant woman, woman dies. Tricity Today, 9 April 2020, https://tricitytoday.com/news/health-worker-molests-pregnant-woman-woman-dies-7430.html |

| 11 April 2020 | Naiduniya | Naiduniya Representative. Madhya Pradesh News: Pregnant woman did not receive treatment, death in MYH, Indore. Naiduniya, 11 April 2020, https://www.naidunia.com/madhya-pradesh/indore-madhya-pradesh-news-pregnant-did-not-receive-treatment-in-in-myh-indore-death-5480436 |

| 11 April 2020 | Asia Net News | Asianet News Hindi. Inhumanity: ANM slaps a pregnant woman in labour room for moaning in labour pain. Asianet News, 11 April 2020, https://hindi.asianetnews.com/bihar/anm-slaps-pregnant-woman-during-delivery-in-jamui-bihar-pra-q8ma4x |

| 17 April 2020 | Navbharat Times | Lockdown: Woman suffering from childbirth, gave birth to child in police jeep. Navbharat Times, 17 April 2020, https://navbharattimes.indiatimes.com/metro/delhi/other-news/woman-gives-birth-to-child-in-police-jeep-while-going-to-hospital/articleshow/75199489.cms%0D%0A |

| 20 April 2020 | Jagran | Srivastava B. Three dead, including pregnant woman in SRN Hospital, all report coronavirus negative. Prayagraj News. Jagran, 20 April 2020, https://www.jagran.com/uttar-pradesh/allahabad-city-three-died-including-pregnant-in-srn-hospital-but-coronavirus-reports-is-negative-in-all-20206796.html |

| 25 April 2020 | Dainik Jagran | Dainik Jagran. Negligence, woman was suspected and the administration performed the last rites. Dainik Jagran, 25 April 2020, http://jagranmp.com/rewa/2020-04-25/14 |

| 26 April 2020 | Hindustan | Hindustan Team. Pregnant woman becomes a football in game of referral. Hindustan, 26 April 2020, https://www.livehindustan.com/uttar-pradesh/bareily/story-pregnant-woman-becomes-soccer-in-referee-39-s-game-3175621.html |

| 5 May 2020 | Dainik Bhaskar | Bhaskar Correspondent. Left the pregnant woman on a stretcher after drip, she died in the wee hours of the morning, referred the dead body, the ambulance staff returned. Dainik Bhaskar, 5 May 2020, https://epaper.bhaskar.com/detail/526010/14101980116/mpcg/05052020/277/text/ |

| 5 May 2020 | Amar Ujala | News Desk Amar Ujala Bureau. Greater Noida: The hospital refused to admit for not getting 30 thousand, pregnant woman was suffering. Amar Ujala, 5 May 2020, https://www.amarujala.com/delhi-ncr/noida/greater-noida-hospital-not-admit-pregnant-lady-because-as-she-unable-to-30-thousand-rupees |

| 7 May 2020 | Hindustan | Hindustan Team. Pregnant woman did not receive treatment, died after delivery at home. Hindustan, 7 May 2020, https://www.livehindustan.com/uttar-pradesh/story-meerut-woman-died-after-delivery-as-she-did-not-get-proper-treatment-3200211.html |

| 11 May 2020 | Navbharat Times | Navbharat Times. Three women stopped from entering the hospital, delivery was done at the gate itself. Navbharat Times, 11 May 2020, https://navbharattimes.indiatimes.com/metro/lucknow/other-news/three-women-stopped-from-entering-the-hospital-delivery-was-done-at-the-gate-itself/articleshow/75661942.cms |

| 15 May 2020 | Dainik Bhaskar | Dainik Bhaskar. After giving birth to son, mother’s health deteriorates, death due to lack of treatment. Dainik Bhaskar, 15 May 2020, https://www.bhaskar.com/local/mp/gwalior/ambah/news/mothers-health-deteriorates-after-giving-birth-to-son-death-due-to-lack-of-treatment-127302627.html |

| 16 May 2020 | Hindustan | Hindustan Team. Doctors did not admit pregnant woman to Upper India, referred to Dufferin. Hindustan, 16 May 2020, https://www.livehindustan.com/uttar-pradesh/kanpur/story-doctors-not-admitted-pregnant-in-upper-india-refer-dufferin-3219441.html |

| 17 May 2020 | Hindustan | Hindustan Team. Pregnant women are not getting treatment in CHC. Hindustan, 17 May 2020, https://www.livehindustan.com/uttar-pradesh/meerut/story-pregnant-women-are-not-getting-treatment-in-chc-3219581.html |

| 17 May 2020 | News18 | Sharma A. Shaming humanity! An 8-months pregnant woman dies due to lack of treatment, the infant could not even open her eyes. News18, 17 May 2020, https://hindi.news18.com/news/uttar-pradesh/kasganj-painful-death-of-pregnant-woman-due-to-due-to-lack-of-treatment-upask-nodgm-3121159.html |

| 18 May 2020 | Dainik Bhaskar | Dainik Bhaskar. Corona suspected woman delivered in isolation ward, no doctor arrived for treatment. Dainik Bhaskar, 18 May 2020, https://www.bhaskar.com/local/mp/news/corona-suspected-woman-delivered-in-isolation-ward-no-doctor-reached-for-treatment-127314476.html |

| 18 May 2020 | ETOI News | Editor. Inhumanity of a god-like doctor, in the absence of money. Etoi News, 18 May 2020, https://etoinews.com/humanity-of-a-doctor-called-god-when-there-is-no-money/ |

| 18 May 2020 | NewsD | New. The condition of a quarantine centre in Nalanda: the pregnant woman moaning for four days, the child died in the womb. Newsd, 18 May 2020, https://hindi.newsd.in/bihar-nalanda-pregnant-lady-suffer-pain-for-4-days-quarantine-center-child-died-in-womb/ |

| 23 May 2020 | First India News | First India Correspondent. Orthopaedic doctor became god for woman in labour pains, delivered before reaching ward. First India News, 23 May 2020, https://firstindianews.com/news/Delivery-of-woman-from-Agra-to-RBM-Hospital-in-Bharatpur-1481590070%09%0D%0A |

| 27 May 2020 | Hindustan | Hindustan Team. Pregnant woman in torture, newborn dies. Hindustan, 27 May 2020, https://www.livehindustan.com/uttar-pradesh/shamli/story-pregnant-woman-in-torture-newborn-dies-3242043.html [Hindi] |

| 28 May 2020 | Dainik Bhaskar | News Correspondent. Woman in pain for 4 hours after caesarean in Eling, doctor and nurse missing, death. Dainik Bhaskar, 28 May 2020, https://epaper.bhaskarhindi.com/2690176/Dainik-Bhaskar-Jabalpur/#page/16 |

| 31 May 2020 | Dainik Bhaskar | Dainik Bhaskar. Charged more for delivery in Ratlam, Hospital fined. Dainik Bhaskar, 31 May 2020, https://www.bhaskar.com/local/mp/ratlam/news/charged-more-for-delivery-in-ratlam-hospital-fined-127358705.html |

References

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. COVID-19, MERS & SARS. 2020 [cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/covid-19

- United Nations Population Fund. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Preparedness and Response: UNFPA Interim Technical Brief – Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights, Maternal and. Newborn Health & COVID-19. Geneva: UNFPA; 2020. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/COVID-19_Preparedness_and_Response_-_UNFPA_Interim_Technical_Briefs_Maternal_and_Newborn_Health_-23_March_2020_.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Social Distancing – Keep Your Distance to Slow the Spread. 2020 [cited 2020 May 21]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/social-distancing.html

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. COVID-19 India. 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/

- Press Information Bureau. Government of India Issues Orders Prescribing Lockdown for Containment of COVID-19 Epidemic in the Country. New Delhi: Press Information Bureau, Government of India; 2020. Available from: https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/PR_NationalLockdown_26032020_0.pdf

- Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA). Order. New Delhi: MHA, Government of India; 2020. Available from: https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/MHA Order Dt. 1.5.2020 to extend Lockdown period for 2 weeks w.e.f. 4.5.2020 with new guidelines.pdf

- Home Secretary. MHA DO Letter. New Delhi: Home Secretary, Government of India; 2020[cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/MHA DO letter dt.14.4.2020 to Chief Secretaries and Administrators for strict implementation of Lockdown Order during extended period.pdf

- Ministry of Home Affairs. Order. New Delhi: MHA, Government of India; 2020. Available from: https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/MHAOrderextension_1752020.pdf

- Jain A. Lockdown doesn’t have to involve harsh police action: An expert explains how. HuffPost India. 2020 Apr 11; Available from: https://www.huffingtonpost.in/entry/coronavirus-lockdown-police-action_in_5e8c231cc5b62459a92e52ae

- Menendez C, Gonzalez R, Donnay F, Leke R. Avoiding indirect effects of COVID-19 on maternal and child health. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;1–2.

- Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB, Stegmuller AR, Jackson BD, Tam Y, et al. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;May 12:1–8.

- Hussein J. COVID-19: What implications for sexual and reproductive health and rights globally? Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;28(1):1–3.

- Jones S, Gopalakrishnan S, Ameh C, White S, van den Broek N. ‘Women and babies are dying but not of Ebola’: the effect of the Ebola virus epidemic on the availability, uptake and outcomes of maternal and newborn health services in Sierra Leone. BMJ Glob Health. 2016;1(3):e000065.

- Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too Far to Walk: Maternal Mortality in Context. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(8):1091–110.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Child Health Programme under NHM. New Delhi:MoHFW; 2019. Available from: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1592997

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. LaQshya. New Delhi: MoHFW; 2019[cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1578508

- Nagarajan R. Covid-19 puts immunisation, ante-natal check-ups on hold. Times of India. 2020 Apr 2[cited 2020 May 20]; Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/covid-19-puts-immunisation-ante-natal-check-ups-on-hold/articleshow/74940038.cms

- Shekhar GC. Heroes Of Lockdown: How A Police Constable & An Auto Driver Helped Two TN Women During Labour. Outlook India. 2020 Apr 18[cited 2020 May 20]; Available from: https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/india-news-heroes-of-coronavirus-lockdown-how-a-police-constable-an-auto-driver-helped-two-tamil-nadu-women-in-labour/350981

- Prerana K. How Lockdown & Apathy from Authorities Are Taking a Toll on Jharkhand’s Pregnant Women & Their Babies. News18. 2020 Apr 21[cited 2020 May 20]; Available from: https://www.news18.com/news/india/how-covid-19-lockdown-and-apathy-from-authorities-are-taking-a-toll-on-pregnant-women-and-their-babies-in-jharkhand-2586815.html

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt of India. Enabling Delivery of Essential Health Services during the COVID 19 Outbreak: Guidance note. New Delhi: MoHFW, Government of India; 2020[cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/EssentialservicesduringCOVID19updated0411201.pdf

- Sama Resource Group for Women and Health v. Union of India and Ors. Order. In the High Court of Delhi at New Delhi, India; 2020[cited 2020 May 20] p. 5. Available from: https://www.livelaw.in/pdf_upload/pdf_upload-373668.pdf

- Mohiuddin Vaid v. State of Maharashtra & Ors. No Title. In the High Court of Judicature at Bombay, India; 2020[cited 2020 May 20] p. 5. Available from: https://www.livelaw.in/pdf_upload/pdf_upload-375218.pdf

- National Health Mission Government of India. LaQshya- Labour Room Quality Improvement Initiative. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2017. Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/RMNCH_MH_Guidelines/LaQshya-Guidelines.pdf

- Office of the Registrar General India. Special Bulletin on Maternal Mortality in India 2016-18. Sample Registration System. 2020[cited 2020 Oct 18]. p. 4. Available from: https://censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/SRS_Bulletins/MMR Bulletin 2016-18.pdf

- Population Foundation of India. Impact of COVID-19 on young people: Rapid assessment in three states, May 2020 (Bihar, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh). New Delhi: PFI; 2020.

- Rukmini S. COVID-19 Disrupted India’s Routine Health Services. IndiaSpend. 2020 Aug 27; Available from: https://www.indiaspend.com/covid-19-disrupted-indias-routine-health-services/

- Cole F. Content analysis: process and application. Clin Nurse Spec. 1988;2(1):53–7.

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15.

- Neuendorf K, Kumar A. Content Analysis. In: Mazzoleni G, editor. The international encyclopedia of political communication. Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell; 2006. p. 221–30.

- Nair H, Panda R. Quality of maternal healthcare in India: Has the National Rural Health Mission made a difference? J Glob Health. 2011;1(1):79–86.

- World Health Organization. Managing epidemics. Geneva: WHO; 2018[cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/managing-epidemics/en/

- Mehta RM, Mehta R, Balaji AL, Mehta H. Perceptions on COVID-19: A ground-level analysis to guide public policy. Lung India. 2020;37:282–3.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Guidance Note on Provision of Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child, Adolescent Health Plus Nutrition (RMNCAH+N) services during & post COVID-19 Pandemic. New Delhi:MoHFW;2020[cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/GuidanceNoteonProvisionofessentialRMNCAHNServices24052020.pdf

- Green A. Maternal health services take a hit amid global lockdown. Devex. 2020 May 25; Available from: https://www.devex.com/news/maternal-health-services-take-a-hit-amid-global-lockdown-97263

- Singh S, Doyle P, Campbell OMR, Rao GVR, Murthy GVS. Pregnant women who requested a ‘108’ ambulance in two states of India. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(3):e000704.

- Basu S. Non-communicable Disease Management in Vulnerable Patients During Covid-19. Basu S. Non-communicable Disease Management in Vulnerable Patients During Covid-19. Indian J Med Ethics. 2020;V(2):103–5.

- Lalwani V. Coronavirus: ‘How do I reach a hospital?’ Cancer and kidney patients worry about 21-day lockdown. Scroll.in. 2020 Mar 25[cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://scroll.in/article/957108/how-do-i-reach-a-hospital-cancer-patients-ask-as-21-day-lockdown-looms-ahead

- Dore B. Covid-19: collateral damage of lockdown in India. BMJ. 2020;369:m1711.

- Thomas G. Death in the time of coronavirus. Indian J Med Ethics. 2020;V(2):98–9.

- Corburn J, Vlahov D, Mberu B, Riley L, Caiaffa WT, Rashid SF, et al. Slum Health: Arresting COVID-19 and Improving Well-Being in Urban Informal Settlements. J Urban Health. 2020;Apr 24:1–10.

- Bhattacharya S, Sundari Ravindran TK. Silent voices: Institutional disrespect and abuse during delivery among women of Varanasi district, northern India. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):1–8.

- Rajalakshmi TK. In search of a road map. Frontline. 2020 May;15–7. Available from: https://frontline.thehindu.com/cover-story/article31544715.ece

- Chatterje P. Gaps in India’s preparedness for COVID-19 control. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):544.

- Editorial. India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet. 2020;395(10233):1315.

- Kurian OC. How the Indian state of Kerala flattened the coronavirus curve. Guardian. 2020 Apr 21; Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/21/kerala-indian-state-flattened-coronavirus-curve

- Schueller E, Klein E, Tseng K, Kapoor G, Joshi J, Sriram A, et al. COVID-19 in India: Potential Impact of the Lockdown and Other Longer-Term Policies. The Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy; 2020[cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://cddep.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/India-Shutdown-Modeling-Slides-Final-2.pdf

- Editorial Team. The Hippocratic Oath Updated. Indian J Med Ethics. 1994;2(4):1. Available from: https://ijme.in/articles/the-hippocratic-oath-updated/?galley=html

- Shrivastava S, Sivakami M. Evidence of ‘obstetric violence’ in India: an integrative review. J Biosoc Sci. 2020;52(4):610–628.

- White Ribbon Alliance. Respectful Maternity Care: The Universal Rights of Childbearing Women. Washington DC: WRA; 2011.

- Dutta SS, Bajpai N, Suryawan S. COVID lockdown hits maternal health services. New Indian Express. 2020 May 16[cited 2020 May 20]; Available from: https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2020/may/16/covid-lockdown-hits-maternal-health-services-2143968.html

- Rasmussen SA, Smulian JC, Lednicky JA, Wen TS, Jamieson DJ. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(5):415–26.

- MacKinnon J, Bremshey A. Perspectives from a webinar: COVID-19 and sexual and reproductive health and rights. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;28(1):1763578

- Kerber KJ, de Graft-Johnson JE, Bhutta ZA, Okong P, Starrs A, Lawn JE. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet. 2007;370(9595):1358–69.

- Ahmed Z, Sonfield A. The COVID-19 Outbreak: Potential Fallout for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. Guttmacher Institute. 2020[cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2020/03/covid-19-outbreak-potential-fallout-sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-rights

- Thapa SB, Mainali A, Schwank SE, Acharya G. Maternal Mental Health in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(7):817-818.

- Yassa M, Birol P, Yirmibes C, Usta C, Haydar A, Yassa A, et al. Near-term pregnant women’s attitude toward, concern about and knowledge of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2020;33(22)3827-3834.

- Langer A, Horton R, Chalamilla G. A manifesto for maternal health post-2015. Lancet. 2013;381(9867):601–602.

- Roesch E, Amin A, Gupta J, García-Moreno C. Violence against women during covid-19 pandemic restrictions. BMJ. 2020;369:m1712.

- Mlambo-Ngcuka P. Violence against women and girls: the shadow pandemic. UN Women. 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 30]. Available from: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/4/statement-ed-phumzile-violence-against-women-during-pandemic

- United Nations. Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women. New York: UNO;2020[cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-en.pdf?la=en&vs=1406