THEME: DISABILITY RIGHTS: ACCOMMODATION, AUTONOMY, AND ADVOCACY

Admission of persons with disabilities into nursing and midwifery courses: Progress made by the Indian Nursing Council

Hareesh Angothu, Sharad Philip, Revathi Somanathan, Krishnareddy Shanivaram Reddy, Deepak Jayarajan, Krishna Prasad Muliyala, Jagadisha Thirthalli

DOI:https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2020.111Abstract

India’s Persons with Disabilities Act, 1995 (PWD Act, 1995) mandated a minimum enrollment reservation of 3% for persons with disability (PwDs) across all educational courses supported by government funding. Following this, the Indian Nursing Council (INC) issued regulations limiting such an enrollment quota to PwDs with lower limb locomotor disability ranging between 40%–50%. The Medical Council of India (MCI) also restricted admissions under the PwD category to PwDs with a lower limb locomotor disability to comply with the Act. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPwD) Act, 2016, which replaced the PwD Act, 1995, raised the minimum reservation to 5% for all government-funded institutions of higher education and extended this reservation to PwDs under 21 different clinical conditions, rather than the seven conditions included under the PwD Act, 1995. Following the enactment of the RPwD Act, 2016, the MCI issued regulations that allowed PwDs with locomotor disability and those with a few other types of disabilities in the range of 40%–80%, to pursue graduate and postgraduate medical courses, while the INC has not made any changes. This article addresses the complexities of inclusion of PwDs in the healthcare workforce, offers suggestions for inclusive measures; and compares the INC admission regulation released in 2019 to the MCI 2019 admission guidelines for graduate and postgraduate medical courses.Keywords: nurse, professional midwife, benchmark disability, inclusion, Indian Nursing Council

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO), in its global nursing forum statement, described nurses and midwife professionals (NMP) as frontline professionals who use an integrated and comprehensive approach, which includes health promotion, disease prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care. They contribute to the reduction of morbidity and mortality, which may result from emerging and re-emerging health problems (1). The American Nursing Council (ANC) describes the dimensions of nursing as the promotion of health and abilities, prevention of injury, alleviation of suffering, and advocacy during care (2). An adequate number of trained NMPs is vital to achieve the sustainable development goals and adhere to the philosophy of “leave no one behind”. The WHO report suggests that there are around 28 million global nursing personnel, among whom 19 million are professional nurses, and the rest are either associate nurses or unclassified (3). An editorial on this report in the Lancet highlighted the inequitable distribution of nurses, with a significant shortage of nurses in Africa, south-east Asia, and the eastern Mediterranean; it also opined that the lack of nurses and midwives could severely affect the universal health coverage goal, one of the sustainable development goals (4). Moreover, in these regions, poorer countries have the greatest shortfall of trained healthcare workers (5). In an economic model based on current demand for healthcare workers, current growth, and estimated production of human resources in about 150 countries, a global shortfall of 15 million healthcare workers is expected by the year 2030 (6). Nursing is also one of the most rapidly expanding healthcare workforces, providing potential career opportunities to many. There is little extant literature about persons with disabilities (PwDs) pursuing training or careers as nurses and midwives. From experiential accounts of PwDs who have had nursing careers, misconceptions about PwDs’ ability to provide safe and effective healthcare seem to be widely shared (7). Legislative, systemic, procedural, attitudinal barriers, and knowledge gaps pose barriers to the entry of PwDs into this rapidly expanding sector.

Disability rights in India

The estimated prevalence of disability varies, based on the conceptual framework and research method used to measure it. In its 2011 report on disability, the WHO cited the World Health Survey’s estimation that 15.6% of persons who were older than 15 years of age had some disability, and 2.2% of adults had very significant difficulty in functioning. The Global Burden of Disease study, cited in the same document, estimated that 19.4% of persons older than 15 years of age had some disability, and 3.8% of adult population had severe disability (8). India, the second-most populous country after China with about 1.2 billion population, had estimated through its census in 2011, that about 22 million Indians had some type of disability (9). Since her independence in 1947, India has enacted two landmark legislations which mandated reservations for PwD in education, employment, and other social welfare schemes to promote inclusion and equal participation. The first was The Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act, 1995 (PwD Act, 1995) (10); and the second was its replacement, The Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPwD) Act 2016 (11). The PwD Act, 1995, mandated that all government-funded educational institutions should enroll a minimum of 3% PwDs across all courses, including professional ones. The RPwD Act, 2016, increased this quantum of PwD reservation to a minimum of 5% in government or government-aided education programmes and codified a minimum of 4% reservations for employment in government institutions for persons with benchmark disabilities (PwBMDs) – a term which refers to persons certified by the relevant authority to have not less than forty percent of a specified disability notified under the provisions of the RPwD Act, 2016 (11). A report by the Ministry of Labour in the year 2019 (12) suggested that only about 42,000 persons were employed under the PwD quota across all governmental organisations. The total number of employees under the Government of India (GOI) is about 3.2 million. This suggests that only about 1% of employees under the GOI are PwBMDs. The RPwD Act, 2016, has become a tool for PwDs to fight for their rightful inclusion across all sectors, including professional medical courses. A few PwDs and disability advocates had filed cases in courts of law against the criteria notified by the Medical Council of India (MCI) for persons having one or other specified disability to pursue medical graduation and post-graduation courses. Sruchi Rathore versus Union of India, Purswani Ashutosh (minor) versus Union of India are some of the cases in which the courts have struck down a few access barriers for the inclusion of Persons with Benchmark disabilities in the medical graduation courses, on par with others (13, 14). The provisions of the RPwD Act, 2016, a few court verdicts as mentioned above, and consistent efforts by advocates for the inclusion of persons with disability into the graduate and postgraduate medical courses led to significant changes in the MCI’s admission criteria for persons with benchmark disabilities. We aim to explore whether the criteria for inclusion of PwDs in the nursing and midwifery professional courses have evolved to reflect this model of disability as well.

Nursing and midwifery professionals in India

The Indian Nursing Council (INC) was established following the enactment of the INC Act 1947 (15). The INC is the regulatory authority and statutory body overseeing the education and licensing of qualified nursing & midwifery professionals (NMPs) in India. The 2018-19 annual report of the INC states that a total of 8,837 nursing educational institutions offered nursing and midwifery training to a total of 3,26,384 persons each year for different courses (16). Such courses range in duration from a two-year Auxiliary Nurse and Midwife (ANM) course, a three-year General Nursing and Midwifery (GNM) course, to a five-year PhD (Doctorate) course. By the end of 2018, about 3 million NMPs were registered under the INC (17). An exploration of PwD admission guidelines into the NMP courses turned up a few notifications by the INC in 2014 and 2019.

A recently reported case is Ms Yasmeen Mansuree vs Union of India, in which the litigant challenged a nursing recruitment notification issued by a GOI-run hospital over the non-inclusion of acid attack victims in the quota reserved for PwDs (18). “Acid attack victim” is listed among the 21 specified disabilities deemed eligible for educational and employment reservations specified in the RPwD Act 2016, if such instance leads to benchmark disability under the locomotor disability category. Global inequity and lack of diversity in medical educational programmes carry significant costs as they may negatively influence potential innovations, and the inclusion of PwDs in the healthcare sector as physicians, nurses, therapists could promote the care of patients with disabilities and their nuanced needs (19). It is also necessary to re-examine the inclusion of PwDs in the Indian healthcare sector because of the following developments:

• a paradigm shift from a medical model of disability to an integrated socio-medical model of disability (20);• provisions under the RPwD Act, 2016, mandating a minimum 4% of jobs across all categories in state-funded or supported establishments for eligible PwDs, and a minimum of 5% seats in all professional courses in state-funded higher educational institutions for eligible PwDs (11);

• lack of evidence to suggest that PwDs as nurses or other healthcare professionals would compromise the safety of patients (21);

• published reports of PwDs’ successful completion of their nursing education, and their ability to fit into a range of selected healthcare services (22);

• technological advances in healthcare over the last few decades including digital stethoscopes, automated blood pressure measuring apparatus, sensor-based recognition of deranged vital functions for patients in intensive care, computer-mediated drug delivery into the body, robotic assistance in surgeries, and software for conversion of text to voice and vice versa, vibration based recognition of alerts for nurses with hearing impairments and others which have the potential to reduce access barriers to learn and perform a range of healthcare services (23, 24);

• changes in teaching methods due to advances in digital technology with augmented reality, and virtual reality-based learning possibilities (25);

• advances in healthcare service delivery modes such as health education through telemedicine (26);

• current and estimated future shortage of nursing professionals to meet healthcare service delivery requirements (6).

The statutory and autonomous bodies, INC and MCI, regulate the nursing and medical education professions, respectively. Eligibility criteria for admission to these courses are largely similar. Methods of training for a few clinical skills and expected competency for a few emergency clinical skills bear similarity. NMPs and medical doctors are required to register with INC and MCI, respectively, after completing their courses. A periodic renewal of their registration and a need to update their knowledge, skills, and advances in treatment have been mandated by both bodies. Considering this and the lack of any published literature regarding the inclusion of PwBMDs in the nursing course, we have also attempted to compare INC and MCI guidelines for the inclusion of PwBMDs.

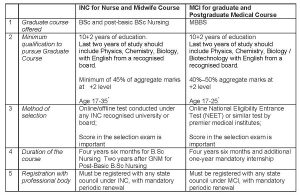

Table 1: Pathways to the nursing or medical professions in India (not for PwBMDs)

* Relaxations in maximum age for entry depends on the course they may choose under INC. [This table is synthesised from information described in admission criteria notified for the admission into these courses (27, 28, 29). As illustrated in Table 1, the minimum eligibility criteria for anyone’s entry into either the NMP course or the graduate medical course (MBBS) is broadly similar.]

Current status of inclusion of PwDs in nursing and midwifery professional courses

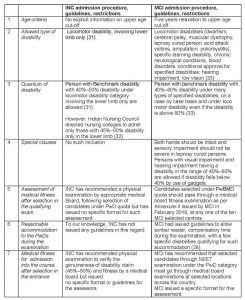

An INC report stated that, by 2019 (16), around 1,25,000 candidates had completed the graduate nursing course (BSc. Nursing) – which is a four and a half year course – annually. Similarly, around 1,20,000 people finished the 3-year diploma course GNM every year. In December 2018, the INC decided to phase out the three-year GNM diploma course and replace it with a three-and-half year BSc Nursing graduate course (30) Within a few years from now, after realising these changes, about 200,000 people would enter the graduate nursing course every year across India. Therefore, a minimum of 10,000 PwBMD could potentially enter the graduate nursing course (BSc Nursing) every year. We could not come across any INC guidelines or notifications on the process of accommodation for PwBMD either during entry, or during the course continuation phase. A comparison of MCI notifications and guidelines for the admission of PwBMD into the graduate medical courses and the INC guidelines suggests significant differences in the approaches to including PwBMD taken by these two statutory bodies. Specifically, aspects of the INC guidelines appear less inclusive, arbitrary, and potentially discriminatory with regard to PwBMD. MCI in the year 2019 notified amended guidelines for allowing candidates into the MBBS course under the PwBMD reservation quota. These guidelines are in consonance with the RPwD Act, 2016, and have expanded the list of conditions under the specified disabilities, making it more inclusive (Table 2).

Table 2. Discrepancies in admission practices for PwBMD of INC and MCI.

Table 2 ─ synthesised from the information notified by the MCI and INC (31, 32, 33) ─ highlights the significant difference in the range of severity of disability for a PwBMD to be considered for admission under the 5% PwD reservation quota. The MCI notified that PwBMD in the range of 40%–80% of measured disability would be eligible to pursue the MBBS course in the absence of specified gross sensory impairments. This inclusive notification is the result of court litigation for greater inclusion of PwDs, and the outcome of efforts by advocates for the inclusion of PwDs in professional courses. Before this notification, an expert committee constituted to examine the inclusion of PwD submitted its recommendations on the criteria for selective inclusion of PwD into graduate medical courses to the president of the MCI (34). These recommendations were criticised for being arbitrary, unfair, and discriminatory (35). Facing an outcry about MCI’s less inclusive approach, the Ministry of Health finally notified more inclusive admission guidelines for PwD aspirants seeking entry into medical courses (29). Disability measurements in the current format as per the guidelines measure the structural or sensory impairment in most cases, and it would be equated to a quantum of disability (36). Such impairment-based disability quantification as 50%, 60%, 80% is arbitrary, simplistic, and reductionist; it fails to reflect the strengths or potential of a PwD. The INC, while notifying PwD admission guidelines in 2019, appears not to have considered the expanded rubric of locomotor disabilities, the added list of other specified disabilities, reasonable accommodation construct, as well as the emphasis on non-discrimination and equality of opportunity as enshrined in the RPwD Act, 2016. It is unclear if the INC included nursing professionals with disabilities while approving such exclusions for the admission of PwDs to the nursing courses. It is worth mentioning that INC had allowed admission for persons with colour blindness into the nursing courses by notification in the year 2018. However, INC had issued guidelines that candidates with colour blindness should wear correcting lenses (37). To our knowledge MCI had not issued any similar notification. It is confusing and concerning that though INC had notified on April 10, 2019, that PwDs with disability in the range of 40%–50% in lower limbs only should be allowed into nursing education, it had issued a letter to all universities admitting nursing students that only PwDs with locomotor disability in the range of 45%–50% in lower limb should be allowed under the PwD quota (31, 32). In addition to eligibility criteria, the explicit inclusion of provisions for scribes, compensatory time, and screen-reader facilities during the exam in the MCI guidelines does not find a place in the 2019 INC guidelines. The INC still considers only PwDs with lower limb involvement and having a disability in the range of 40%–50%, or perhaps 45%–50%, to be eligible for admission into graduate nursing courses under the 5% PwD reservation quota.

These norms could – and should – be improved to make them more scientific, inclusive, and non-discriminatory. This could be done by expanding the spectrum of disabilities considered for reservation, through a reasonable accommodation construct, emphasis on non-discrimination, and equality of opportunities. We also believe that there are complexities in involving PwDs in professional medical and nursing courses; ethical and safety concerns related to patients also need to be addressed. To have a deeper understanding of this issue, we have examined challenges in the inclusion of PwDs in the NMP professions in the United States of America (USA).

Inclusion of PwDs in nursing courses: Ethical and pragmatic views

Misconceptions, and beliefs about poor abilities of PwDs have shaped the societal practices of exclusion of PwDs, across a range of occupations, particularly healthcare-related occupations. In the healthcare sector, the patient’s safety is of primary importance. Standard procedures for healthcare delivery, treatment guidelines, standards in clinical skills necessary for professionals, and establishment of professional bodies to regulate all such matters, exist primarily to safeguard patients.

Such exclusion of PwD entry into healthcare-related occupations like nursing appears to exist across countries, including the developed countries like the USA and the United Kingdom (UK). Though the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 in the USA barred any discrimination based on a person’s disability, it was only after the enactment of the Americans with Disability Act (ADA) 1999, that many US nursing schools opened their doors to candidates with disability, by providing reasonable accommodation for admission into nursing courses (38). Unfortunately, there is scant published literature about the impact on patient care of healthcare workers with disabilities. It is argued that such discrimination and exclusions are not limited to occupations directly involving patient care; but also extend to areas of scientific research in healthcare funded by State agencies. Recent data suggests that PwDs as principal investigators (PIs) for research funding are less likely to get funding from the US National Institute on Health (NIH) in contrast to those who do not have a disability or who do not declare it. A decline in the percentage of PwDs who received funding as PI is also reported (39).

The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) released a series of documents on this issue: The Americans with Disabilities Act: Implications for Nursing Education” and “White Paper on Inclusion of Students with Disabilities in Nursing Educational Programs” are two examples (40). Minority nurse is an online US publishing forum from Springer, which posts the success stories of nurses with disabilities, suggesting that, in spite of significant impairments, PwDs can pursue nursing careers successfully (41). The UK Royal College of Nursing (RCN) also issued a range of career options for nurses with severe ill health or impairments. The RCN suggested that there were numerous possibilities like health advisory through the telephone, teaching, counselling, administration, task coordination, assessing disability, promoting health, and clerical roles where nurses with impairments may be accommodated (42, 43). The US National Organization of Nurses with Disabilities (NOND), through its campaign for employment, conducts awareness programmes about the range of challenges and the range of possibilities (44). Perhaps INC’s less inclusive approach of allowing only PwDs with mild lower limb disability may be based on the assumption that such candidates will not have major difficulties in acquiring skills which are described as essential skills for a practising nurse. It may also be due to the assumption that PwDs with one hand (and other types of disabilities) would never be able to master the necessary clinical skills to become nurses. Perhaps to dispel such misconceptions, NOND had posted video demonstrations on YouTube titled “How to insert intravenous cannula with one hand”, and “How to administer intramuscular injection with one hand” (45).

Neal-Boylan argues that nursing educators worry about the abilities of nurses with impairments to acquire the necessary clinical skills. The tendency of people to focus on disability rather than on ability, misconceptions about what a nurse with disability can do, and unsubstantiated concerns about a nurse with disability jeopardising patient safety, are among the many significant barriers to entry of PwDs into nursing courses (46, 47, 48). We believe such attempts at inclusion would not be without challenges at various levels, and career trajectories of physicians and nurses with disability can be challenging without reasonable accommodation (49). We submit that assumptions regarding nursing tasks, such as feeding the patient, positioning or transporting the patient, performing intravenous cannula insertion, changing wound dressings, taking notes while attending clinical rounds, performing vaginal delivery alone, caring for the new-born child alone, and performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) alone, may have shaped the current INC guidelines. A presumption that a PwD with upper limb disability would never be able to achieve such skills is challenged by a few registered nurses in the US, who have only one hand (50, 51, 52). In our opinion, such assumptions about clinical skills of nurses with disabilities may be also shaped by a belief that skills learned as part of nursing training would be permanent. However, the retention and refinement of competencies in clinical skills among persons working in the healthcare sector is dependent on their continuous medical education and training. These perspectives often fail to consider the full range of services within the scope of nursing practice. The traditional assessment methods of whether or not a nurse has a set of minimum essential skills like the ability to stand for a few hours, or to lift a particular weight, are barriers for PwD inclusion into the healthcare workforce and deserve to be re-examined.

Telemedicine guidelines issued by the GOI, though intended for registered medical practitioners only, hint that the model of healthcare delivery in the future would be different from the traditional in-person approach. Ignorance or an unwillingness to consider possibilities – such as nurses with walking difficulty monitoring telemetry in a cardiac unit, or a nurse with one hand performing quality checks, or a nurse with hearing impairment using telecommunication devices for the deaf to perform routine tasks – will preserve barriers to the inclusion of PwDs in graduate nursing courses. Nurses with physical disabilities could effectively discharge their duty as faculty, as health educators and advisors (53, 54). The story of Helen Cherry, the first person with deafness to become a nurse in 1977 could become an inspiration for PwDs with hearing impairment to pursue a nursing career (55).

Alternative approaches that may aid the inclusion of PwDs into nursing courses

Policymakers and members of the INC’s executive body who have the authority to carry out modifications or amendments to the nursing course admission guidelines could consider the following approaches to make them more inclusive:

-

• INC should conduct, fund or supervise research to examine the inclusion of PwDs into the nursing professions. Qualitative research involving PwDs who have been nurses in the last few decades, nursing supervisors, trainers, colleagues who had worked with nurses with a disability, and patients who received care from nurses with disability will aid the development of fairer inclusion or exclusion criteria for nursing admission under the PwD category.

• An examination of practices related to inclusion of nurses with disabilities during the training period and at the workplace in a few developed countries like the USA , the UK and Australia, could be helpful in this regard (56). For instance, training resources for nursing students with disabilities, and resources for faculty to train nursing students with disabilities, like those developed by the York College of Pennsylvania could be prepared by INC to aid such inclusion (57).

• A committee with PwD as members to address issues related to assisting PwDs during their training period, guiding the universities for better inclusion, for the destigmatisation of PwD entry into the nursing field, and to prevent any discrimination would be helpful. Specialised technology-savvy volunteer professionals with or without disabilities can assist in identifying workplace situations and solutions.

• Sensitisation of nursing trainers, administrators and supervisors about the social model of disability and the effect of reasonable accommodation in training and at the workplace (for improved and safe performance by nurses) could break down attitudinal barriers.

• Guidelines to institutions to conduct periodic reviews of their programmes to provide reasonable accommodations for training, testing, and practice, would aid the institutions to adhere more closely to the spirit of inclusion of all under the RPwD Act of 2016.

• Screening questions and voluntary disclosures at the time of licensure or registration would provide appropriate opportunities to identify issues and need for assistance (58).

• PwD inclusion or exclusion in graduate nursing courses should be based on a case by case approach and only after careful examination of fitness on providing reasonable accommodation (59).

• Maintaining a register for nurses with disabilities, including them in various INC subcommittees while preparing any minimum technical standards and appropriate methods of teaching and of performance assessment could be a few among many measures necessary to maintain the spirit of the RPwD Act, 2016. Consent and a respect for privacy concerns must also guide the creation of such registries.

• It would be prudent to include the social model of disability and disability competencies in the current and future nursing educational curricula to embrace the spirit of the RPwD Act, 2016, which mandates the inclusion of disability rights in educational curricula (60).

• Learnings from regulations in other countries could be a first step in the direction of broadening our understanding of PwD inclusion in nursing courses. The Drexel University of Philadelphia adopted a policy of assessing the technical standards for admission of PwD into the graduate nursing courses for their academic progress, and for the assessment of their successful completion of graduation (61).

Conclusions

INC’s prior notification to comply with 3% reservation under the PwD Act, 1995, and the current admission guidelines that “only PwD with 40%–50% locomotor lower limb disability would be admitted under 5% reservations meant for the PwD category, assume that nursing acumen and skill have an inverse relation to the quantum of disability a PwD may have (62). Current INC guidelines categorically exclude several PwDs who are otherwise eligible from pursuing graduate medical courses when compared to the MCI graduate course admission guidelines. Considering the change in the disability construct under the RPwD Act, 2016, and the legal imperative to provide reasonable accommodations for persons with disability, the INC guidelines may attract criticism and legal challenges.

Notifications such as those issued by the INC for categorical exclusion of PwDs having above 50% disability, in contrast to a more inclusive approach taken by the MCI, may raise doubts about the willingness of such professional and statutory bodies to facilitate the inclusion of PwD as envisaged in the RPwD Act, 2016, and towards fulfilling India’s commitments under the United Nations Convention on Persons with Disability (UNCRPD).

A more inclusive approach by INC for PwD admissions into the nursing courses is required, not only to comply with the RPwD Act, 2016, but also to foster motivational success stories like the story of Leenie Quinn, adaptive athlete, nurse & rugger, born with one hand (63). Opening the doors to the inclusion of PwDs by INC could lead to the creation of a larger number of qualified nursing health professionals, and thereby reduce the shortage of nursing professionals in the country. Nurses with disabilities could perform a broad range of much needed public health and quality assurance activities such as health screening interviews, health education, medical notes maintenance through voice typing, nursing administration, and teaching if assisted with reasonable accommodation. Advocates for the inclusion of PwDs in nursing assert that they may become better nurses, because they have experience of suffering and going through challenges in performing their life activities. Such experiences could help them in relating to patients for providing better empathetic care (64).

Lastly, disability may occur at any time in one’s life. Planning for the inclusion of PwDs at the stage of admission into nursing courses could spur innovations that will help nurses who may become disabled during the course of their careers. Creation of technical standards for the assessment of clinical skills and clinical competencies in nursing students with or without disability should be considered, instead of assessing the ability of a nurse to lift an arbitrary weight as a measure for the assessment of ability to turn the patient on a bed (65). Creation of a system to periodically assess the support required for nurses with disability, during their training and after training at their work place can be a beginning towards the creation of inclusive healthcare delivery systems. (66).

Conflicts of interest and funding support: None declaredAcknowledgments: The authors wish to acknowledge Dr Barbara Cohen, PhD, JD, RN, (New York, USA) for her gracious editing and research efforts provided in the preparation of this article.

References

- World Health Organization. Nursing and Midwifery Workforce and Universal Health Coverage: Forum Statement. 2014 May 14-15[cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from https://www.who.int/hrh/events/22May2014ForumStatement.pdf?ua=1

- American Nurses Association. Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.) Silver Spring, MD: ANA; 2015 [cited 2020 September 5]. Available from https://www.lindsey.edu/academics/majors-and-programs/Nursing/img/ANA-2015-Scope-Standards.pdf

- World Health Organization. State of the world’s nursing 2020- Executive Summary. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331673/9789240003293-eng.pdf

- The status of nursing and midwifery in the world. [Editorial]. Lancet. 2020 Apr 7 [cited 2020 Sep 5]: 395(10231); 11-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30821-7.

- World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory. Data repository. Nursing and midwifery personnel. Updated 2020 Jun 23[cited 2020 September 5]. Available from https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.HWFGRP_0040?lang=en

- Liu, J.X., Goryakin, Y., Maeda, A. Bruckner T, Scheffler R. Global Health Workforce Labor Market Projections for 2030. Hum Resour Health 2017 Feb 3; 15(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0187-2

- Neal-Boylan L, Smith D. nursing students with physical disabilities: dispelling myths and correcting misconceptions. Nurse Educ. 2016 Jan-Feb;41(1):13-8. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000191.

- World Health Organization. Summary. World Report on Disability. 2011[cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70670/WHO_NMH_VIP_11.01_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. India at a glance -Census 2011 data: Population. 2011[cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from http://censusindia.gov.in/Census_Data_2001/India_at_glance/glance.aspx

- Ministry of Law, Justice and Company Affairs, Government of India. The Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act, 1995, Act 1 of 1996. [cited 2020 May 22]. Available from http://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A1996-1.pdf

- Ministry of Law and Justice, Govt of India. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016. Act No. 49 of 2016. Sec.2. 2016 Dec [cited 2020 May 22]. Available from https://indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2155?view_type=browse&sam_handle=123456789/1362

- Ministry of Labour, Government of India. Annual Report 2018-19. 2019 Jul [cited 2020 May 22]. Available from: https://labour.gov.in/annual-reports

- Supreme Court of India. Sruchi Rathore v Union of India. 2017 Aug 18 [cited 2020 Sep 4]. Available from: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/102595185/

- Supreme Court of India. Purswani Ashutosh (Minor) v Union of India. 2018 Aug 14 [cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/159789271/

- Indian Nursing Council Act, 1947, Act no. 48 of 1947. 1947 Dec 31[cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.indiannursingcouncil.org/pdf/inc-act-1947.pdf

- Indian Nursing Council. Annual Report 2018-19. New Delhi: INC; Date unknown [cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from: http://www.indiannursin gcouncil.org/pdf/Annual_Report_INC_2018_19

- Indian Nursing Council. Types of Nursing Programs. New Delhi: INC; 2012-13[cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from https://www.indiannursingcouncil.org/nursing- programs.asp?show=prog-type

- Delhi High Court. Yasmeen Mansuree vs Union of India. W.P(C) 6897/2018.) 2018 Sep 26 [cited 2020 May 5]. Available from: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/88592525/

- Meeks LM, Maraki I, Singh S, Curry RH. Global commitments to disability inclusion in health professions. Lancet. 2020 Mar 14;395(10227):852-3. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30215-4.

- UN General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Resolution / adopted by the General Assembly, A/RES/61/106. 2007 Jan 24 [cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.refworld.org/docid/45f973632.

- Marks BA. Jumping through hoops and walking on egg shells or discrimination, hazing, and abuse of students with disabilities? J Nurs Educ. 2000 May;39(5):205-10.

- Marks B, McCulloh K. Success for students and nurses with disabilities: A call to action for nurse educators. Nurse Educ. 2016 Jan-Feb;41(1):9‐12. doi:10.1097/NNE.0000000000000212.

- Swarup S, Makaryus AN. Digital stethoscope: technology update. Medical devices (Auckland, N.Z.)/ 2018 Jan 4; 11, 29–36. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S135882. eCollection 2018.

- blog.diversitynursing.com.. Erica B. Robots designed to help nurses, not replace them (January 3rd, 2017). Available from http://blog.diversitynursing.com/blog/robots-designed-to-help-nurses-not-replace-them

- Saxena N, Kyaw BM, Vseteckova J, Dev P, Paul P, Lim KTK, et al. Virtual reality environments for health professional education. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Oct; 2018(10):CD012090. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012090.pub2.

- Rutledge CM, Kott K, Schweickert PA, Poston R, Fowler C, Haney TS. Telehealth and eHealth in nurse practitioner training: current perspectives. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017 Jun 26; 8:399-409. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S116071.

- Indian Nursing Council, Eligibility Nursing Programs. New Delhi: INC; 2012-13 [cited 2020 May 7]. Available from http://www.indiannursingcouncil.org/nursing-programs.asp?show=elig-crit

- National Testing Agency, Ministry of Education. National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (UG) 2020 – Bulletin Information. New Delhi: NTA;2020.[cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from: https://ntaneet.nic.in/Ntaneet/ShowPdf.aspx?Type=50C9E8D5FC98727B4BBC93CF5D64A68DB647F04F&ID=AC3478D69A3C81FA62E60F5C3696165A4E5E6AC4

- Board of Governors in supersession of Medical Council of India. Guidelines regarding admission of students with “Specified Disabilities” under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016. Appendix H. 2019 Feb 4.[cited 2020 May 9]. Available from: https://mcc.nic.in/PGCounselling/home/ShowPdf?Type=E0184ADEDF913B076626646D3F52C3B49C39AD6D&ID=BE4D979EF9808E41A6ADF3BBEFC4331248E88604.

- Indian Nursing Council. Notification regarding Single entry level for nursing- phasing out of GNM course. Notified on 2019 Sept 19 [cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.indiannursingcouncil.org/pdf/Single_Entry_level_for_Nursing_1110.pdf

- Indian Nursing Council. Resolutions approved by the general body in its meeting held on November 25 & 26th, 2017 on admission criteria for disabled candidates under nursing programmes. Notified on 2019 Apr 10[cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from: http://indiannursingcouncil.org/pdf/Admission_Criteria_for_Disabled_Candidates_Notification.pdf

- Indian Nursing council. Admission Guidelines F.No.22-10/Univ.-2019-INC. 2019 Apr [cited 2020 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.indiannursingcouncil.org/pdf/Letter_to_universities.pdf.

- Board of Governors in supersession of Medical Council of India. Regulations to further amend the “Graduate Medical Education Regulation, 1997.Appendix H-1 2019 May 13. [cited 2020 Sept 5]. Available from; https://ntaneet.nic.in/ntaneet/ShowPdf.aspx?Type=3C5339881A1720DEED325383E8C3839B7748D254&ID=77DE68DAECD823BABBB58EDB1C8E14D7106E83BB.33

- Medical Council of India. Submission of the comprehensive report regarding guidelines for admission of persons with specified disabilities to the President Medical Council of India in pursuance of the communication from ministry of health and family welfare. 2018 June 5 (Cited 2020 Oct 9). Available from https://mcc.nic.in/UGCounselling/Home/ShowPdf?Type=50C9E8D5FC98727B4BBC93CF5D64A68DB647F04F&ID=F6E1126CEDEBF23E1463AEE73F9DF08783640400

- Singh S. Medical Council of India’s new guidelines on admission of persons with specified disabilities: Unfair, discriminatory and unlawful. Indian J Med Ethics. 2019 Jan-Mar [cited 2020 Apr 20]; 4(1) NS: 29-34. Available from: https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2018.064.

- Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities, Govt of India. . Guidelines for the Assessment of Specified disabilities under the RPWD Act 2016. New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment; 2018 Jan 4 [cited 2020 May 9]. Available from: http://disabilityaffairs.gov.in/content/page/guidelines.php

- Indian Nursing Council. Resolution approved by the governing body in the meeting held on colour blind candidates for nursing courses. 2019 Feb 28 [cited 2020 Sep 6] Available from https://www.indiannursingcouncil.org/pdf/COLOUR_BILIND.pdf

- Helms L, Jorgensen J, Anderson MA. Disability law and nursing education: An update. J Prof Nurs. 2006 May; 22(3):190‐6. doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.03.005

- Swenor BK, Munoz B, Meeks LM. A decade of decline: Grant funding for researchers with disabilities 2008 to 2018. PLoS One. 2020 Mar 3;15(3): e0228686.

- Marks B, Ailey S. White Paper on Inclusion of Students with Disabilities in Nursing Educational Programs for the California Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities (CCEPD). 2014 Jun;10.13140/RG.2.1.4741.9606.

- Minority Nurse-The Career and Education Resource for the Minority Nursing Professional. Minoritynurse.com. [cited 2020 Jun 2]. Available from: https://www.springerpub.com/journals/minority-nurse.html

- Royal College of Nursing. Managing your career with ill health and disability-Changing directions. Rcn.org.uk. Date unknown [cited 2020 Jun 3]. Available from https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/your-career/ill-health-and-disability

- Royal College of Nursing. Disability Passports-The RCN Peer Support Service Guide; 2007 Dec [cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.rcn.org.uk/get-help/member-support-services/peer-support-services/disability-passport

- National Organization of Nurses with Disabilities. Resources for nurses with disabilities, nursing students with disabilities, nurse educators/administrators. Nond.org. Date unknown [cited 2020 June 2]. Available from: https://nond.org/what-we-do/resources/

- National Organization of Nurses with Disabilities. Nursing educational videos. Date unknown [cited 2020 Jun 5]. Available from: https://nond.org/what-we-do/educationtraining/open-the-door-film/

- Neal-Boylan L. Miller M. How inclusive are we, really? Teach Learn Nurs. 2020 Oct; 15(4):237-40. doi: 10.1016/j.teln.2020.04.006.

- Shpigelman CN, Zlotnick C, Brand R. Attitudes toward nursing students with disabilities: Promoting social inclusion. J Nurs Educ. 2016 Aug 1;55(8):441-9. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20160715-04.

- Neal-Boylan L, Hopkins A, Skeete R, Hartmann SB, Iezzoni LI, Nunez-Smith M. The career trajectories of health care professionals practicing with permanent disabilities. Acad Med. 2012 Feb;87(2):172-8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823e1e1c.

- Sowers J, Smith M. Nursing faculty members’ perceptions, knowledge, and concerns about students with disabilities. J Nurs Educ. 2004 May;43(5):213-8.

- Ella J. Prosthetic hand allows nursing student to follow her dream. Seattletimes.com. 2010 Nov 30[cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/health/prosthetic-hand-allows-nursing-student-to-follow-her-dream/

- Staff Reporter. Nursing Student inspires others with one hand. Ardmoreite.com. 2016 Feb 5 [cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from https://www.ardmoreite.com/news/20160205/nursing-student–inspires-others-with-one-arm

- Loss of arm creates meaningful new purpose for New Jersey nurse: CBSN. New York. 2019 April 30[cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from https://newyork.cbslocal.com/2019/04/30/new-jersey-nurse-one-arm/

- Rao N. An exceptional resource for would-be nurses with disabilities: Insightinto diversity.com. 2015 March 31[cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from https://www.insightintodiversity.com/an-exceptional-resource-for-would-be-nurses-with-disabilities/

- Resetar A. What’s it like to become a nurse with hearing loss? Hearinglikeme.com. 2018 Sep 20[cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.hearinglikeme.com/being-a-nurse-with-hearing-loss-2/

- RCN Magazine.rc.org.uk. [internet] Breaking boundaries. Rcn.org.uk. 2017 Dec [cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.rcn.org.uk/magazines/bulletin/2017/december/breaking-boundaries

- Ailey SH, Marks B. Technical standards for nursing education programs in the 21st Century. Rehabil Nurs. 2017 Sep/Oct; 42(5):245-53. Doi: 10.1002/rnj.278. PMID: 27197703.

- Davidson PM, Rushton CH, Dotzenrod J, Godack CA, Baker D, Nolan MN. Just and realistic expectations for persons with disabilities practicing nursing. AMA J Ethics. 2016 Oct 1; 18(10):1034-40. Doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.10.msoc1-1610.

- Horkey E. Reasonable academic accommodation Implementation in clinical nursing education: a scoping review. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2019 Jul/Aug; 40(4):205-9. Doi: 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000469.

- Singh S, Cotts KG, Maroof KA, Dhaliwal U, Singh N, Xie T. Disability-inclusive compassionate care: Disability competencies for an Indian Medical Graduate. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(3):1719-27.

- Drexel University website. Accommodations, Disability Resources from the Office of Equality and Diversity; Philadelphia, PA. Date unknown[cited 2020 May 29] Available from https://drexel.edu/oed/disabilityResources/students/Accommodations/

- Indian Nursing Council. Resolutions F.No.1-5/2014. New Delhi: INC; 2014[cited 2020 Sep 5]. Available from http://nmcouncil.ap.nic.in/circular/1.pdf

- Leenie Quinn, Adaptive athlete, nurse and rugger, born with one hand. Headsntales Blog. 2015 Nov 8 [cited 2020 Sep]. Available from: http://www.headsntales.org/blog/10

- Neal-Boylan L. Having a disability may make you a better nurse. Workplace Health Saf. 2019 Nov; 67(11):567-8. doi: 10.1177/2165079919860541.

- York University website. Information for Applicants with Diagnosed Disabilities. Date unknown [cited 2020 May 30]. Available from https://futurestudents.yorku.ca/requirements/applicants-diagnosed-disabilities

- Matt SB, Maheady D, Fleming SE. Educating nursing students with disabilities: Replacing essential functions with technical standards for program entry criteria. Journal on Postsecondary Education and Disability. 2015; 28 (4): 461-8. Available from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1093588

- Howlin F, Halligan P, O’Toole S. Development and implementation of a clinical needs assessment to support nursing and midwifery students with a disability in clinical practice: part 1. Nurse Educ Pract. 2014 Sep;14(5):557-64. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2014.07.003.