THEME: TRUST IN HEALTHCARE

Trust and trust relations from the providers’ perspective: the case of the healthcare system in India

Sumit Kane, Michael Calnan, Anjali Radkar

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2015.045

Abstract

Commentators suggest that there is an erosion of trust in the relations between different actors in the health system in India. This paper presents the results of an exploratory study of the situation of providers in an urban setting in western India, the nature of their relations in terms of trust and what influences these relations. The data on relationships of trust were collected through interviews and focus group discussions with key informants, including public and private providers, regulators, managers and societal actors, such as patients/citizens, politicians and the media.

Introduction

The latest report on the global burden of disease shows that India accounts for around 20.8% of the global burden of disease and 24.6% of the burden of disease in developing countries (1). Within the country, most of the burden is borne by the more than 400 million poor people (2). A government-run healthcare sector co-exists with a vast, diverse and rapidly growing for-profit private sector, which mostly requires out-of-pocket expenditure. While public healthcare services are used largely by the poor, the services of private healthcare providers, across all levels of care, are used by rich and poor alike (3, 4), though the type of private providers used by each group is different. The bulk of the private providers are small enterprises, centred around an individual professional; however, corporate entities with large-scale facilities are increasingly becoming major players. The government (national, state and local), along with professionals’ associations, are mandated and expected to play a key role in the governance and stewardship of the health system.

The health system has consistently fallen short of almost all its goals, particularly of equitable improvements in the health status of the poor, the quality of care provided to them, and social and financial risk protection for them (5, 6). At the core, these failures appear to be failures of governance and stewardship, and the failures of the state and professional associations to uphold their mandates. Regular exposés in the mainstream media (7) and academic literature (8, 9) point to people’s growing frustration with corruption in the health system, and the failure of the government and professional associations to check it. The rising incidence of violence against healthcare professionals and health facilities attests to the same thing (10, 11, 12). An analysis of this situation warrants the adoption of a broader and more fundamental approach, one which focuses on the abuse and erosion of citizens’ “trust” in the systems that deliver healthcare to them, and in the institutions mandated to oversee this “entrustment”.

De Costa et al (3) have shown that there has been erosion in trust even within the healthcare system, and that there is generally a low level of trust between private providers, public providers, health service managers and policy-makers.

Trust and its importance in the health system

Trust is recognised as significant for providing effective healthcare across national systems and provider contexts (13, 14, 15). Rowe and Calnan (16) contend that “the cost of failing to recognise the importance of trust and to address the changing nature of trust relations could be substantial: economically, politically, and most important of all, in terms of health outcomes” (p.6). The widespread erosion of trust and the consequent disenchantment with the healthcare system in India can push people into the hands of quacks and crooks (17), reduce adherence to treatment, compel people to hop from provider to provider, and provoke defensive medicine which drives up costs and compromises the quality of care – all of which ultimately lead to poor health outcomes for all. As Chatterjee (9) and Subha Sri (18) illustrate, the brunt of this failure of trust is borne disproportionately by the poor and vulnerable, who have meagre means, few choices and not much of a voice.

Trust is believed to be particularly important in the context of healthcare because it is a means of bridging the vulnerability, uncertainty and unpredictability inherent to the provision of healthcare. Trust is seen to be made up of intentional trust and competence trust, with the latter being embedded in the former (19). Relationships of trust have, therefore, been characterised by one party, the trustor, harbouring positive expectations regarding the competence of the other party, the trustee (competence trust); the trustor also expects that the trustee will work in his/her best interest (intentional trust). According to the definition of trust adopted in this study (20), the trustor and trustee have allied interests, and trust is seen as a process of communication which enables the trustee to manage vulnerability and uncertainty (21, 22). This definition reflects competence trust in that the trustee is seen to be competent enough to bring about the required outcomes.

In contrast to the sizable amount of literature worldwide that assesses trust from the patient’s perspective (23), studies examining either the value or impact of trust from the practitioner’s perspective or from an organisational perspective are in short supply (19). From an organisational perspective, trust is believed to be important in its own right, ie it is intrinsically important for the provision of effective healthcare and has even been described as a collective good, like social trust or social capital (24). The specific organisational benefits that might be derived from trust as a form of social capital include a reduction in transition costs due to lower costs of surveillance and monitoring and the general enhancement of efficiency (25). The literature also suggests that relationships of trust in the health workforce – between providers, and between providers, health service managers and regulators – may also influence the quality of patient–provider relationships and the levels of trust in these relationships (26, 27, 28). In their conceptual approach to organisational trust, Gilson and colleagues (26) classify the chains of relationships of trust into different tiers, in which “trust in the employing organisation”, “trust in supervisors” and “trust in colleagues” form part of “workplace trust”. Workplace trust might influence professional perspectives and practices, which, in turn, might shape the relationship of trust between patient and professional. According to Gilson (25), relationships of trust between providers, and between providers and regulators can result in better communication and improved cooperation between these actors; the strength of these relations can directly influence patients’ trust in providers by shaping their perceptions of the technical competence and fairness of the providers. Gilson (25) contends that when providers are inclined not to trust their patients, and/or are not given sufficient time with them due to bureaucratic pressures and restrictions, they may end up adopting uncaring attitudes towards specific groups of patients or towards all patients in general; this can undermine the quality of the patient’s interactions with the health system. Such attitudes can quickly get entrenched through the formalisation of practices such as defensively prescribing often unnecessary investigations and medicines, and routinely involving other experts. In addition, with the increasing use of shared care for patient management, both in primary and secondary care, trust between clinicians is even more important (26, with reliability as well as honesty and competence having been shown to be important components of trust (19). This proposed link between organisational trust and interpersonal trust implies both a linear pathway and a top-down approach, not least because of the hierarchy and asymmetry in the power relations between health service managers, clinicians and patients. However, there are circumstances where patients or their advocates can have an influence on organisational trust through their relations with clinicians, ie by voicing their complaints.

Another major level of trust in this context is institutional trust, which relates primarily to trust in the institution of medicine or the healthcare system at the macro level (19). Some authors (29) refer to it as systems trust, which signifies “accountability and the checks and balances and systems that maintain fairness, preventing competence or malign intent” (p.9). However, the relationship between systems trust and interpersonal trust is not straightforward, in that trust in a particular individual clinician or in a local health service or practice might not convert into trust in the institution in its entirety or vice versa. Thus, it may be claimed that there has been a decline in trust in medicine as an institution or in the healthcare system, although the levels of trust in individual doctors and other professionals may still be comparatively high (19).

There has been little research in the area of relationships of trust in healthcare in India, but the subject is increasingly drawing attention (30, 31). This paper explores the situation from the provider’s perspective, eliciting views on the nature of providers’ relations with other actors, including health service managers, complementary medical practitioners, and patients/citizens.

Methods

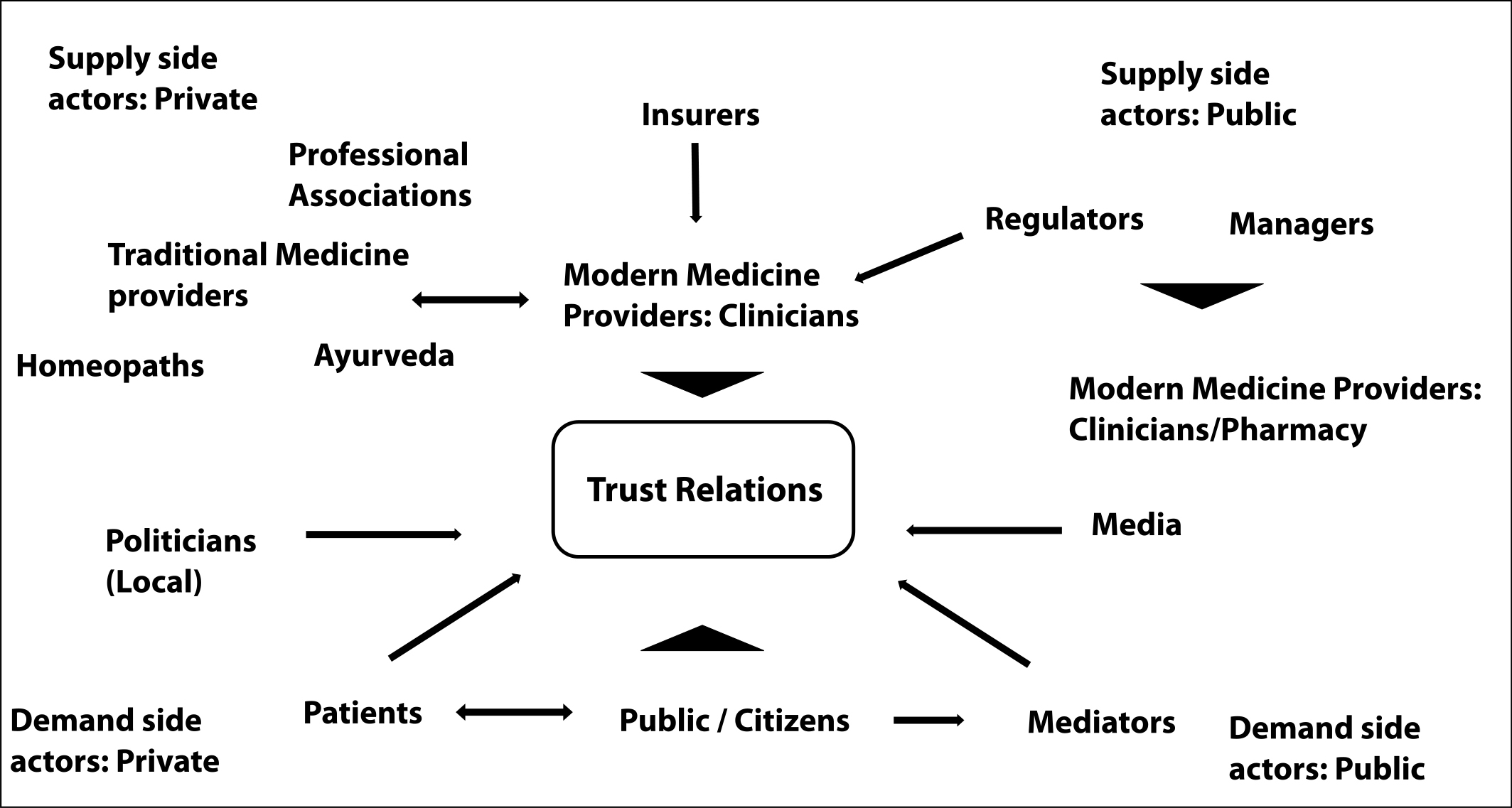

Design: This study adopts a sociological approach to understand how providers experience trust in their relations with society; how wider social structures influence the meaning and demonstration of trust; and in particular, how changes in the organisation, delivery and regulation of healthcare, and broader social changes, affect relationships of trust between providers, as well as between providers and regulators. The literature was reviewed to specify the research questions, and to map and identify the categories of informants and their potential relations of trust, as well as the influences on these relations. The insights gained were refined on the basis of the data analysis and with the help of inputs from our informants. Figure 1 presents the results of the mapping exercise. The study was conducted in an urban setting in western India.

Sampling: The informants for the interviews and focus group discussions were selected purposively. To ensure that the reference points of the informants’ experiences and views would be comparable, informants knowledgeable in the maternal health domain were selected. Informants with potentially different perspectives of the subject under study were selected so as to expose multiple facets of the situation. Anattempt was made to seek those who played more than one role and could reflect on the subject from various angles. The informants included (numbers mentioned in parentheses): a) service users (citizens) (10); b) private providers (4 – two allopaths, one ayurveda, and one homeopathy practitioner); c) public provider –medical doctor (1); d) public health services manager who is also an academic (1); e) representative of a professional body(body responsible for regulation of professional conduct and practice) – who is also a private provider (1); f) civil society representative(1); g) media person (1); h) pharmacist (1); i) health insurance company manager (1); and j) local politician (1). All service users were women, residents of urban or peri-urban areas, from the middle/lower middle class, and literate. Of the 10, six participated in a focus group discussion; while four were interviewed face-to-face.The focus group discussion preceded the interviews. We refer to our citizen informants as service users to distinguish them from other informants who were professionals.

Recruitment: The informants were identified through the contacts of the researchers (SK and AR), who have been working in the region for many years, through a snowball sample of referrals by the initial informants. For instance, the informant from civil society, who was the first to be interviewed, pointed out that health insurance companies were becoming an increasingly important actor and suggested that we interview someone knowledgeable from the industry. We accepted the suggestion and identified the informant through one of the faculty members of the university. Service users were recruited from two locations: the volunteer group of a corporate social responsibility initiative of a local industry, and a women’s self-help group under the National Livelihoods Mission.

Context factors: These independently, and/or concurrently influence the actors, their intent, behaviors and performance. These include, but are not limited to factors like: Social networks, Gender norms, Cultural practices, Beliefs, Economy, Environment, Political Situation, Security, and Governance.

Data collection: All informants were assured of confidentiality and offered the opportunity to refuse participation or recording. All but one agreed to participate; the head of the local medical association met us, but could not come for the interview and referred us to a colleague. Written informed consent was taken from all informants, both for the interviews and recording of the interviews. The interviews and focus group discussions were conducted in Marathi as well as English; some informants used both languages. The data were collected over a two-week period, using a topic guide developed on the basis of an initial literature review, and also on the experience of one of the researchers (19) who had carried out similar studies in other parts of the world. Digital recordings were transcribed verbatim; thus, the transcripts were a mix of Marathi and English, and these were analysed as such (two of the authors, SK and AR, are fluent in English and Marathi). Informants’ quotes were translated into English at the time of analysis and writing up of findings.

Analysis: The Framework Method was used for the thematic analysis of the transcripts (32). A provisional coding framework was developed on the basis of a literature review, earlier experiences of similar studies (19), and the field notes. New codes were added and some existing codes were modified as the data analysis progressed. At the end of each day, the three researchers shared their field notes and impressions with each other, and discussed and analysed the findings of the day (in English, as one of the researchers, MC, does not speak Marathi). They also agreed upon any modifications to be made to the line of enquiry, as well as to the topic guide. Data were collected until theoretical saturation was reached and no more meaningful constructs emerged. The transcripts were analysed with Nvivo 10 by SK, in consultation with AR and MC. Using the NVivo output, narratives were developed on the main themes. All responses were anonymised when developing the narratives.

Ethical considerations and approvals: The study was conducted in a large urban region in western India, an area where thousands of healthcare providers, both public and private, deliver services. Our sampling method, coupled with the small sample size, means that our informants cannot be identified. The data management processes followed to ensure anonymity and confidentiality made doubly sure of this. The profile of informants was such that they had no hesitation about sharing their thoughts. This was perhaps also because, as many informants stated, the subject studied is discussed regularly in society and people are vocal about it. In addition, the detailed informed consent ensured that the informants knew about the nature and scope of the study, our boundaries and their entitlements. The study was approved on the condition that informed consent would be taken and the confidentiality and anonymity of the informants be maintained. It was also necessary to obtain the approval of the Director General of Health Services of the state as some serving public officials were to be interviewed, according to the original protocol (ultimately, none of the serving officers was interviewed, although approval was received).

Findings

The first part of this section consists of a discussion of themes related to the changing context of healthcare in India. This is followed by a discussion of two major themes – “cut practice” and “role of technology” – and their effects on the relations of trust on the provider’s side. In the later sections, relations between private providers and regulators, private providers of different systems of medicine, and private and public providers are examined.

Changing nature of healthcare: from a “family doctor-based care model” to a “corporate culture-based care model”

In general, the informants felt that the major change in the nature of healthcare delivery is the gradual disappearance of the general practitioner who is based in and serves the community.

“Now the concept of the family doctor is diminishing so people are… if it is doctor they are visiting only in the rarest of rare occasions. They might not be having trust in him …and people think doctor may be right or may be wrong … people think that he is making money.” (Informant from the media)

The private providers pointed out that people like to repose trust in “someone” to help them make health- and care-related decisions, and that this someone is often a private provider who plays (or had played) the role of a family doctor for their family.

“I have been practising here (in this community) for a long time … when a patient comes to you a few times … for delivery … then later they say let us show our child here … a relationship develops … you become the family physician. They consider the family physician like a family member … then they share their household problems … you know …social problems, too … they say ‘Madam, this happened’, and then one needs to counsel and guide …” (Private practitioner 2)

A quote from a citizen informant illustrates this poignantly, “All of us go there. Uncles, aunts, my mother in law, everybody. The clinic is nearby and he (the private provider/family doctor) does a lot for us, that’s why we go there. Without asking my family doctor I don’t do anything”. (Service user 4)

The “family doctor based care model” is increasingly being replaced by a “corporate culture” based care model. The former, as the above quotes illustrate, lends itself more easily to the development of trusting relations between patients and provider; the latter, as the following section illustrates, less so. This change seems to be central to the changing nature of trust relations between society and healthcare providers, and amongst healthcare providers.

Marketisation of healthcare

According to our informants, market forces are aligned in such a way today that the family doctor-based care model is becoming increasingly unsustainable in major urban settings. The costs involved make it unviable to establish and operate private practices – at a service fee acceptable to people –in urban areas.

“A regular medical graduate does not have the kind of financial resources that one now needs to establish his own clinic, definitely not in a big city … it is very expensive.” (Professional body representative – private provider)

Another private provider, a general practitioner, implied that the corporatisation of healthcare was abetted by the regulatory arrangements, and opined that, eventually, small entrepreneurs would be pushed out of the market. She was frustrated with this changed situation, and felt that it meant the beginning of the end of community-based family practices. She warned that society would have to bear the consequences of this commercialisation, through rising costs due to indiscriminate investigations and hospital admissions.

According to one private provider, “Care provision is becoming difficult and expensive, and who can establish these big hospitals … it is these industrialists who can invest lots of money … a regular doctor cannot invest this kind of money …” (Private provider 2)

Marketisation of medical education: perceptions of trustworthiness of private medical college graduates

The informants also reflected on how the changing nature of entry to medical training and medical training in general has shaped the way people look at doctors, and how it has shaped the relationship between doctors and patients. One informant indicated that the common knowledge that one could get admission, both for undergraduate and postgraduate medical studies, in the many private medical colleges, not necessarily on merit, but by paying large sums of money, had sown seeds of doubt in people’s minds about the competence of doctors.

“(There are) … those who are coming new. Those who don’t deserve admission in the medical college and they get admission by hook or crook.” (Private provider 1)

“Since these private medical colleges have come, Ithink there is some element of doubt about the doctors who have been trained in these private medical colleges … there is a difference … people now wonder … where did you study … people wonder if this doctor is someone who got admitted into medical training just paying money … they wonder if he is someone who paid for his grades … whether he has really studied anything at all.” (Private provider 2)

It appears that doctors who have trained in the new private medical colleges are not entirely trusted by their colleagues who trained in public medical colleges, both in their competence and, to some extent, their intentions. Doctors who have trained in private medical colleges probably know how some of their co-professionals, and perhaps some patients, view them. Since doctors are required to display their degree certificates in their offices, their patients would know where they have received their training. This knowledge might also subtly influence the way these doctors view their patients and practise medicine.

“Cut practice”: a few rotten apples

All the doctors interviewed acknowledged that, often, doctors get paid when they refer patients to others, advise diagnostic tests or prescribe specific medicines. All, however, emphasised that while this practice, called “cut practice”, was probably common, it was not universal.

“Really speaking, there is a lot of unethical practice …and people know about it.. ya, and people know about it.” (Public provider)

“As the saying goes, one rotten mango doesn’t mean all mangoes are rotten. I concede that it can affect, but who is it going to affect the most? The new people joining the profession.” (Private provider1)

All the doctors, the regulator and the health service manager labelled “cut practice” unethical, and felt that it was a major reason for the erosion of trust in the medical profession. The doctors stated that they had been approached by touts of various private hospitals, with offers of commissions for referrals.

“There are so many of these on the prowl …coming from specialist physicians, cardiologists … to get us to send patients.” (Private provider 1)

“They come …but I don’t believe in this types of practices …” (Private provider 3)

This perception was affirmed by the politician; on being asked if people had doubts in their minds about whether doctors were taking ‘cuts’,” she replied:

“Not just doubts .. people are convinced that this is the case … and that it is at a very big scale .. yes.” (Politician)

The private providers interviewed indicated that they chose not to be party to such practices. To a great extent, they defined their identities as upright professionals by distancing themselves from those “others” who indulged in such practices. This “othering” (33) was a regular feature of the language the informants used to disapprove of such practices, and to claim and occupy high moral positions; the “others” were placed on a morally inferior plane, and the informants’ identities were defined by contrast. All the informants offered many explanations – not necessarily excuses – as to what had led to this situation. A common one was that the high investment costs – both for training in a private medical college and investment to start one’s own practice – drove doctors to resort to such practices.

“You tell me … if someone has spent 10 million rupees to establish a practice, then to cover the minimum interest rate of 12% per annum, he must at least make 100,000rupees per month … from Day 1 to cover these costs … how is he going to make that kind of money … and do we expect him to have the guts to say to someone who has referred a patient for surgery… that ‘no this patient doesn’t have appendicitis, I won’t operate’?” (Private provider 1)

The private providers indicated that unlike themselves (they were well established, and well past their professional peaks), the younger medical doctors who were in the early stages of practice, were rather frustrated and disillusioned with what they were experiencing in the profession. They indicated that this was also possibly the case with many specialists who expectedly had a referral-based practice. They urged us to explore this in depth. One informant added that doctors of the younger generation were effectively “trapped”.

“The situation is that the young generation (of doctors) is trapped … Now nobody is satisfied with a graduate degree, everybody decides that they should have post-graduation and now in cities … you must have super-specialist degrees.. This is the trend. Suppose you are a super-specialist … you need to have a CT scan facility… you need to have an MRI facility … then you need to take a loan … to pay it you must have an assured business, this much, if not you are in loss. Simple logic then … if I don’t want a loss then I must meet my target … the young people are trapped.” (Health services manager)

The providers we interviewed displayed a certain resigned acceptance of the situation. While we did not probe, none ventured any reflection on whether the situation could have been even partly due to falling professional standards or weak oversight by professional and regulatory bodies.

While all the service users were aware of the problem, their views were relatively more mixed, and perhaps more understanding of doctors indulging in “cut practice”. When one of them was asked whether she feared over-prescription and overcharging by private providers or “cut practice”, she said:

“Not really … I don’t feel that way because … they must have their own problems, that is why they take … a little bit is OK. After all it is someone’s occupation … as a doctor (occupation) they have got to make money.” (Service user 2)

Another added that people’s way of looking at doctors and their trust in them had not changed much.

“It hasn’t changed .. what has happened is that doctors don’t want to take any chances anymore. For even small things they ask you to get tests, sonography. That wasn’t the case before .. now they first tell to get tests and only then treat.” (Citizen 3)

This willingness to accept the risk of being overcharged might signal a sense of inevitability, and might indicate an absence of hope for justice – a clear pointer to the broader stewardship failure in the health system. This may however in some ways also point to the fact that people have not totally lost trust, but that perhaps the nature of trust is changing. However, it definitely indicates that there is room for rebuilding trust. This argument, however, needs to be examined further. For instance, unlike the affluent user who can be critical and shop around for providers, it might be more difficult for those who have less means to be critical. They may be effectively being forced to trust, as they cannot afford to be critical. This is illustrated by the following interaction regarding private providers advising repeated sonographies from specific sonologists,

“P1: On follow-up after a sonography, they say now we will do it again in 2–3 months. The doctor must be receiving some kickbacks .. that’s why he sends (again and again). F: Do you really think this could be the case? P1: That is all decided .. I send, so they have to take (the pregnant woman for sonography). One has to understand … why refer to that specific sonologist? P2: Why not to an intelligent doctor? P1: Even if we say we like to go somewhere else .. some insist ..one can then understand that there is a link. P2/3: From that … one can understand. F: And yet you still go to whoever you are sent to? P1: Because when we are told … one has to go.” (Focus group discussion)

This was affirmed by the politician. When asked if people had doubts about whether doctors were taking “cuts”, she replied:

“Not just doubts .. people are convinced that this is the case … and that it is at a very big scale .. yes.” (Politician)

The private providers we interviewed, also expressed disappointment and exasperation over the situation, and came across as honest professionals keen on serving society, and wishing to change the situation. One private provider said,

“I tell people (medical professionals)… People should know … the poor patients on whom we learnt our medicine .. in the public hospitals … we owe them something; we owe something to society too ….We have to give back.” (Private provider 1)

Importance of personal manner in the building of trust

The importance of building and cultivating trust and reputations – with patients and within communities – emerged as a major theme. Communicating well and giving patients time were identified as critical factors for the development and maintenance of trust-based relations between doctors and patients (and communities). The following quotes reflect the providers’ thoughts on this issue.

“After some sessions they are just like family to us.” (Private provider 3)

“So if they find that somebody is ready to listen, they are (pause)… they are always happy.” (Private provider 4)

“Some patients have … have family problems… mostly females have those problems … so when we talk about their daughter-in-laws, about their husbands, whatever …just by having a few words also they are relaxed … and they come.” (Public provider)

These findings confirm what Baidya et al have reported from Tamil Nadu (34). They are also echoed to an extent by some of our service user informants. A doctor who is personable and has an affable manner, however, is not enough for them – they expect providers to be competent, too, and find it easier to trust such providers. In many ways, it is a given, an embodied form of trust.

“Good service, not needing to wait long … and you know how it is, if you are given Attention.. then for the patient .. if the doctor does these things.. then ofcourse you like that doctor. Interviewer: So giving time and attention is really very important, ..eh?

Citizen 1: “It is, but not the only thing … giving time is okay,..but finally it is all about what medicine he writes for you.” (Service user 1)

Role of technology in the building of trust

The private providers indicated that the providers’ reputations also depended on other factors which, too, could contribute to winning the patient’s trust. For example, patients were more likely to trust providers who worked in a health facility – whether a small private one or a large corporate one –with sophisticated equipment. They were dismayed by the changing nature of healthcare and the fact that people now placed greater trust in services characterised by superior technology and facilities.

“.. they feel that machines can be (pause) … relied upon, because they feel that machines work .. like science .. perfect science.” (Private provider 1)

Others opined that in urban areas, where there is less of a sense of community due to the mobile population, it is easier for patients to trust new and superior technology and better facilities instead.

“We must take note of the background of the people in the big cities like Nagpur, Bombay, Pune. We have many migrant populations now; these people do not know the unique situations (and people) in the areas they settle in; so they have this habit of checking everything. Earlier people had the opportunity to build relations .. faith-building .. like a family … small village … now these (the new arrivals) people do not have that opportunity. They do not have the advantage of being part of a society. They do not trust themselves and they do not quickly trust other people.” (Representative of professional body)

The following two quotes reflect the informants’ thoughts on how trust in the competence of professionally managed organisations, which have extensive facilities and use modern technology, is slowly replacing the more personal relationships of trust formed with the local healthcare provider.

“The doctors’ face is now lost…what is replacing it now is technology .. sophisticated technology. Now you trust the big nice building .. all this nice infrastructure, all this I am getting .. now that’s what you trust .. rather than the person … people now trust the physical .. the outer looks more.” (Public health manager)

“Then there is the attraction of a big set-up .. you may not trust the place but you go because everything is under one roof.” (Private provider 2)

Breakdown of trust between regulators and providers

Private providers disapproved of the regulatory interventions that they were now subject to. It was not clear whether they disapproved of all regulatory intervention, but they clearly disapproved of the way regulations were implemented by the regulatory authorities. The private providers we interviewed indicated that their peers did not trust the state regulators at all. They indicated that the common experience amongst private providers was that the regulators harassed them, and they had no choice but to make informal payments. The distrust was so acute that it dominated our conversations to the extent that we could not elicit much response to our probing about whether a more nuanced regulatory regime was required to check the unethical practices and the erosion of trust.

“Ah … there is a regulatory system, but usually there are so many doctors in India that the government fails miserably every time.” (Private provider 3)

Asked about the role of regulators and their interaction with them, another private provider responded:

“Nothing … they have nothing to do with us … I mean they just want to harass us. They put their fingers on some regulations, and then that is the pretext they need.”

When probed as to why the regulators would do this, the response was:

“They have a personal interest .. nothing else but money .. and if someone wants to be honest and walk on the straight line, he will be harassed more … the only thing is filling their pockets .. that’s all, nothing else”. She added, “On top of that, there are so many regulations that they are really making it impossible.” (Private provider 2)

Private providers also drew attention to the spate of legal and regulatory changes in the area of healthcare provision, and specifically mentioned the Consumer Protection Act, Pre-Conception, Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act and Medical Establishment Act. According to them, many of these regulations had been abused, leading to a situation in which private providers had begun to feel increasingly afraid of litigation and legal action. This had made them less trusting of their patients. However, they added that this was not the case for all providers, or for all kinds of patients. For instance, this kind of situation was more likely to be faced by specialists, who interact with patients on a one-off basis. General practitioners were more likely to face such situations at the hands of new patients with whom they had not had an opportunity to develop a relationship, as might those working in hospitals and corporate entities. Private providers who offered laboratory diagnostic services hardly ever faced such situations.

The civil society informant, while critical of the medical profession and the way private practices were run, confirmed the above.

“If you look at the trust relations (between private doctors and regulators) in the health system, then they (doctors) look at it like they (regulators) will bring laws and then they will extract money from us; this is how they view it, and they have concrete evidence because in the implementation of PCPNDT Act it has happened exactly like that. So it is not only perception, it is their experience also.” (Civil society member)

The health services manager and regulator agreed that private providers were extremely distrustful of regulators.

“Basically, yes, basically the private sector believes that it is a (pause) ‘police raj’ .. Means … come here … if you are not fulfilling, but if .. if you give something, some commission, some benefits, I will just ignore it.” (Health services manager)

He added that the distrust was mutual.

“The first assumption (amongst the regulators) is that they are not following the rules and regulations and therefore, it is always with suspicion.”

However, he said, this blind lack oftrust was not well founded:

“That is the assumption on private side and this is the assumption on government side.”

The informant from the professional body agreed that this was the case, and said that this was so “because there is hardly any interaction” between the two.

The provider–regulator relationship appears to be characterised by an overwhelming feeling of distrust. The providers think that the regulatory regime is ineffective and allows many local regulatory personnel to abuse it to extort money. The regulators believe –perhaps for valid reasons –that private providers are out to make money at all costs and cannot be trusted.

Trust between providers from different systems of medicine

An exploration of the providers’ decisions on referral, and the reasons behind these decisions, indicated that the providers, both public and private, referred their patients to specific providers.

“I know two or three good gynaecologists, two or three good physicians, or two or three good radiologists. So my references will be to those doctors only, because I trust them and treatment given by them will be perfect treatment, and investigations will be done properly, so I have that trust in them. So I refer to them.” (Private provider 3)

All the providers maintained that their referral decisions and relations with the providers to whom referrals were made were based on “trust”. The basis of this “trust” included the qualifications or professional reputations of those to whom referrals were made, or the fact that earlier referrals to these providers had yielded good results. This was almost always accompanied by a confidence in their own judgment regarding the competence of these providers.

“You know how it is … one agrees with someone’s line of treatment. Over time, one becomes sure about getting results from a particular doctor.” (Private provider 2)

“Yes .. sometimes …we refer to nearby (private) hospitals. We know certain names over the years … know some doctors personally, through the patients we see here. From the treatment (given to the patient referred) we understand.” (Public provider)

Allopaths or practitioners of modern medicine (both in the public and private sectors) unanimously expressed distrust of those ayurvedic and homeopathic practitioners who practise and prescribe modern medicine without a licence or the training to do so. The professional regulator (of modern medicine) and the health services manager felt the same. Their implicit contention was that these providers charged much less (their input costs being lower) than modern medicine-based general practitioners did, and thus were undermining the latter’s establishments and the market at large. They were, however, accepting of those ayurvedic and homeopathic practitioners who practised what they were trained for, and had congenial relations with them. The allopaths interviewed did not refer their patients to homeopathy or ayurveda practitioners; they did, however, know that some of their fellow allopaths did so.

The private ayurveda practitioner and homeopath both exclusively practised their own system of medicine, and reported that their relations with practitioners of modern medicine were congenial and characterised by trust. They spoke of how both they and the providers of modern medicine with whom they worked viewed each other’s systems of medicine as being complementary. They also said they had formed relationships of trust to serve their patients’ needs. Asked about their relations with practitioners of modern medicine, including whether they referred patients to these practitioners, the homeopathy practitioner responded:

“Yes. Especially in skin disorders, when they find that the patient is not improving or he is getting side reactions from allopathic medicines, then they refer them to homeopathy.

“… now about within last 5–6 years, I have seen that this, we can say, this egoistic approach is now going down. Because this they know … there are many things that allopathy does not have medicine for that. So even if they say no … no … we are the best, if the allopathic doctors gets some problem which is not curable with allopathy, he will come to homeopathy himself. So now that ego factor is going down a lot.”

The ayurveda practitioner also agreed:

“… now the pattern is very changed, means the young generation (of practitioners of different systems of medicine)… they are very, very,very much cooperative.”

The private ayurveda and homeopathy practitioners both acknowledged with some disapproval that many of their peers, particularly in rural areas, prescribed modern medicines even though they were not trained to do so. Some key informants and modern medicine practitioners said that according to their experience, ayurveda and homeopathy were in vogue only among the urban middle classes, and that the rural populace had greater trust in modern medicine. As a case in point, they mentioned that almost all ayurveda and homeopathy practitioners working in rural areas prescribed modern medicines.

The service users we interviewed trusted and used modern medicines more than other types, but also said that they trusted ayurveda in the case of certain kinds of illnesses. They did not have much to say about homeopathy.

“Around here, people take more of allopathic medicines .. (Q. More?) … Yes … you see, with ayurveda you have to follow dietary restrictions and all, and its effects also take time – many days … Of course, it cures the disease from its roots, but it takes time and one gets impatient … and then all these diets …so around here, people prefer allopathic.” (Service user 2)

“At our place, I mean at my in-laws’ place, now .. here .. after all these issues .. everybody trusts allopathy .. our regular doctor. But at my parents’ place (in a city nearby), they trust ayurvedic medicines; they still give all these ‘kadhaas’.” (Service user 2)

This preference for allopathy and the fact that the informants trusted it more than the other systems is related to the definite and quick results of allopathic medicines. As the following interaction in the focus group discussion illustrates, the trust in ayurveda sits comfortably beside the confidence and trust in allopathy.

“F: While you were explaining your experience, you mentioned that you later sought ayurvedic treatment – my question to you all is do people trust one pathy more than others? P4: People trust allopathy more. F: Is it? P4: People also trust ayurveda, but you know how it goes – it’s a bit slow to act. P3: Indeed slow to act. P4: I mean ayurveda works slowly; in allopathic you get quick relief. P2: Yes, ayurveda doesn’t relieve quickly. F: So people think like this? P3: Yes. P2: Yes. P1: And there are no side-effects of ayurvedic medicines. There is benefit, but usually little. P2: And late .. and also one cannot say if there will be any benefit. P4: But people trust allopathy more.”

Relationship between public and private providers

All the private providers felt that the facilities and care in the public sector were poorer than in the private sector. However, they did trust the competence of their peers in the public services.

“Public hospitals…they have a lot of variety of patients.Two or three colleagues of mine are there .. One is a gynaecologist. Very, very brilliant doctors are there who are working in the public hospital…”. (Private provider 3)

The service users had an equal amount of confidence in the competence of the doctors working in the public sector.

“Q: So you say that if you go to a public facility, you will save money, but does that mean that the doctors there are good? A1: The doctors are good … they are good.A2: Yes, the doctors are good. Q: Why do you say so? A1: Doctors there are good. A2: Now you see … how it is .. there are good doctors .. when you are talking of public services .. the doctors are bound to be good ..right .. experts… Q: What exactly do you mean….A1: Means more educated … maybe more experienced. A2: Experienced doctors. A3: They have qualifications, they have experience.” (Focus group discussion, citizens)

The private providers were aware of the operational and managerial constraints under which public providers work. One of them pointed out that this situation made matters worse for those who could not afford private services.

“Aaa .. actually, the hospital set-ups in public sectors are overcrowded in India. So even if the doctor is good who is working there he doesn’t have time to see so many patients. Absolutely impossible. The poor class is actually … the poor patients are most worst sufferers in all this system.” (Private provider 4)

One of the private providers felt that public services used to be better and that poor management had led to the deterioration over the last two to three decades.

“When I was studying (in a government medical college), people would come from all over for treatment of complex conditions, conditions which could not be managed elsewhere. That was how it was (with public services) then. Now … what has happened .. in these 10–15 years, everything has changed. People in a public hospital do not put their hearts into their work ..because .. they don’t have facilities, and the management has become so poor.” (Private provider 2)

The public provider mentioned that working in the public services had its own challenges, including, but not limited to, the fact that people considered these services inferior.

“Yaa… from my point of view .. people think if they pay money for consulting, they think that they are getting a proper good advice. They come here, they pay only 10 rupees… and whatever the general medicine we give .. we are giving them medications at such a low cost .. We know they go outside and throw the medicines … They feel that it is such a low level means the medicines must not be good, the doctors must not be good whatever their ideas are…There are some people who absolutely go outside and throw the medicines.” (Public provider)

Overall decline in trust in society at large?

Many informants, other than the service users, commented that there had been an erosion in trust, as well as in honesty of intent, at the level of society at large. They felt that relations of trust in the health system must be examined in this context.

“Generally, in society.. now.. people trust each other less .. police, politicians, even family members. So this is an aspect of it. The reduction in patients’ trust of doctors, or of doctors’ trust of patients, is a part of this.” (Civil society representative)

“I think there is something very much fundamentally wrong in the society which has to be taken care of … What is correct? What is wrong? You know.” (Insurance company manager)

“Earlier, people used to consider doctors as almost gods. I have seen it with my own eyes – people prostrating in front of doctors (my father) ..saying’I was saved because of you’ … from there to the situation now ..it is a big difference.” (Politician)

Many informants, including some doctors, were of the view that the widening gulf between doctors and their patients – particularly in terms of money – was an important reason for the erosion of trust and deterioration of the relations between them. People grudged the accumulation of wealth by doctors, who were thought to beprospering on the strength of others’ misery and helplessness. Speaking about the matter in the context of the widening economic inequalities, the politician said:

“In the long run, everybody suffers. As inequalities increase, it is all about economic inequalities …. the unrest in society will increase. It will become difficult for everybody.” (Politician)

The service users, however, seemed to view the situation differently. While all of them recognised that there had been a decline in trust in various spheres of public and social life (state, judiciary, police and fellow citizens), they did not think that the overall societal situation had a bearing on trust in the healthcare system. Probing this matter did not yield much insight into the effect of the societal situation on the trustworthiness of the health system or the other relations within the system.

Discussion and conclusions

The aim of the study was to explore relationships of trust in the healthcare system from the providers’ perspective. This consisted of an examination of the nature of such relations and what influences the shape of these relations.

It is problematic to explore the subject of trust relations in Indian society as it is not considered morally or culturally acceptable to say that one does not trust someone. For this reason, our informants were somewhat hesitant to make allegations or moral judgments about others. The only exception was the private providers, who expressed their views on the untrustworthiness of the public regulatory authorities unequivocally. The Indian people have had a long tradition of expressing anti-establishment views openly.

The healthcare providers, private and public alike, were open to talking about their perception of their own trustworthiness and their general experience with relations of trust. However, while they acknowledged that there was growing and widespread distrust, they distanced themselves individually from this state of affairs. Thus, they almost defined their professional morality and identity as being in contrast to the “others” –what some have called the process of “othering” (33). The size and scope of these “others”, and the extent to which this morality matches the standards that the larger body of professionals strives towards, remain to be seen. A greater and more nuanced insight into this can form the basis for developing interventions. The providers emphasised that they personally trusted everyone – colleagues, competitors, their patients, generally, and the financers/insurance companies (to a lesser extent) – but not the regulators. The private providers had no doubts about the trustworthiness of colleagues whom they knew or knew of. However, they were not confident that unknown “other” professionals upheld the principles necessary to make the medical profession a trustworthy one. They expressed frustration both at their own inability to do anything about it and about the fact that not much was being done about it. Similarly, the representative of the professional body expressed a sense of inevitability and helplessness about the situation. Societal spokespersons, such as the informant representing civil society, and the local politician, also implied that the situation was a result of professional bodies’ lack of capacity to act, as well as their poor track record in stewardship of the medical profession.

While all the providers held that trust had to be earned and be maintained, they were unhappy with the erosion of blind trust in the profession. The practitioners of modern medicine spoke of stress due to challenges or threats to their professional power, discretion and privilege. They faced stress because of the confusion created perhaps by the challenges to their historically transmitted identity, which was constructed during training and regularly reinforced by society. The confusion was complicated further by the fact that the expectation of a privileged status, hitherto taken for granted, was being simultaneously upheld and challenged by societal actors and institutions.

The problem of “cut practice” in healthcare has been well documented in the Indian literature (35, 36, 37). It is common knowledge that doctors receive “cuts” when they make referrals, yet patients follow their advice regarding referrals. The informants seemed to strongly believe that doctors would place patients’ well-being above their own personal (commercial) interests. People seemed to have the “optimistic expectation” that doctors would ensure their well-being, despite the higher costs of care. There was also evidence of embodied trust in the doctor’s competence. Even if the informants did not fully trust the doctor’s financial intent and motives, they were convinced that he/she would act in their best interest, medically. The doctors however did not make this distinction; they tended to view the situation only in terms of erosion of trust, brought about by a minority or “a few rotten apples” in the profession.

Although the informants were particularly concerned about “cut practice”, and appeared to think that this issue was important for citizens, the service users themselves seemed to show some empathy with, or at the least some understanding of, the provider’s position in relation to their involvement in such practices. This perspective expressed by service users might reflect Gilson’s (25) argument that those who are more vulnerable with lesser resources tend to be more trusting as they cannot afford to be critical due to lack of alternative sources of help. This may also reflect the difference or lack of close fit between the levels and perceptions of trust in the health system as an institution and trust relations at the interpersonal level between practitioner and patient. Thus, the perception of the widespread use of “cut practice” might contribute to the general lack of trust in the system at the institutional level but this does not always manifest itself at the interpersonal level between professionals and patients, where trust relations might be shaped by other influences such as familiarity and personal experiences and knowledge.

Relations between private providers and regulators were characterised by a mutual lack of trust. Regulators seemed to view private providers as driven by money and fair game for extortion. Private providers felt that regulators used the regulations as a pretext to extort money. We must critically examine the lack of faith that both medical professionals and communities have in current regulatory responses to healthcare delivery problems. If we gain a better understanding of the situation, we can identify opportunities to rebuild trust in these important relationships, and better manage healthcare services.

Trust in the relations between private and public providers appeared to be based on the competence of the provider. While public providers did not trust the intent of the larger body of their peers working in the private sector, they did trust specific providers on the basis of their personal experience and familiarity with them. Amongst doctors who had graduated from public medical colleges, there was an element of distrust about both the financial motives, and to some extent the competence, of doctors graduating from private medical colleges. These views were justified with the oft repeated, but suppositious arguments that pressures to recoup costs were the likely driver of the alleged money centeredness.

Trust relations between providers of different systems of medicine appeared to be based on earned trust, earned through interaction and relations developed on a personal basis, and an individual matter; while the ayurveda and homeopathy providers trusted the competence of the allopathy providers and the system of allopathic medicine to deliver results, this sense was not reciprocated by the allopaths, who were ambivalent about the legitimacy of other systems of medicine. In addition, patients tended to trust practitioners who used modern medical technology in their practice which may have led to a preference for allopathic medicine. This evidence raises questions about the viability of any policies aimed at integrating different systems of medicine. Further research needs to explore these questions in more detail as the story emerging from this study contained mixed messages about the relationship between allopathic medicine and ayurveda and homeopathy, with a lack of trust emerging at the systems level but harmonious relations apparent at the interpersonal level.

It was expected that caste would be reported as an influence in trust relations. However, all the informants, including the service users, shrugged the question off without much hesitation, though the interviews were conducted by locals and the caste question was asked in a frank and open way. Patients explicitly stated that trustworthiness was related to competence and familiarity. It could be that in the context of healthcare – a major sphere of social life – people no longer repose trust in providers or make care-seeking decisions on the basis of caste. However, it has been argued that caste has been invisibilised and has escaped scrutiny in Indian society (38). Further research is needed to explore this question and a more sensitive methodology must be developed to get beneath the invisibility of caste and its possible influence on trust in the health system.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study is perhaps the first to examine trust relations amongst those on the supply side of the health system in India and, more broadly, in low and middle income countries, particularly the situation of private care providers. Given the diversity of actors involved in healthcare provision in India, and the pre-dominant role played by private care providers, this study is pertinent as it exposes key issues vis-a-vis trust relations of private providers; in doing so it also sets the stage for innovative areas of research with potentially important implications for population health outcomes. Beyond India, this study is also one of the few empirical investigations on trust relations as experienced by healthcare providers (19).

The study has its limitations. Providers working as employees in private corporate hospitals were not interviewed, nor were their managers. If Gupta’s (36) experience is anything to go by, these providers’ and managers’ professional and relational situation and experiences are likely to be very different. Given the growing corporatisation of healthcare delivery, they need to be understood better. The private providers interviewed were all established practitioners, and all general practitioners; their views on the state of trust relations within the health system might be different from those of private providers who are younger, or have a referral-based or specialist practice. All service user informants were women, and it is possible that men have different views and experiences and that trust relation is a gendered phenomenon. Similarly, all service user informants were from the middle to lower middle class, and urban; rural, poorer citizens may have different points of view. The study was conducted in one part of India, and some of the findings may not apply nationally and across regions. Informants, particularly the non-medical professionals, referred to different levels of care when expressing their views; one can expect the nature of trust relations to vary across primary care services, higher levels of services, and diagnostic services; this study was unable to disentangle this post facto, and its scope was in any case insufficient to cover these possible differences. Also, relations of trust on the provider’s side are not merely about relations amongst doctors and regulators. Other intra and inter-organisational trust relations in the health system, trust relations amongst different cadres of health workers (nurses, auxiliaries, physiotherapists, laboratory staff, other staff, and doctors), could also have a bearing on the community’s trust in the health system. However, this was beyond the scope of our work.

In conclusion, this exploratory study exposes potentially important issues around the state of trust relations in the supply side of the health system, particularly in the stewardship of the healthcare system in India; these deserve further and more extensive examination.

References

- IHME. Global Burden of Disease. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2013.

- Sumner A. Where do the world’s poor live? A new update. IDS Working Paper 393. 2012. Institute of Development Studies, Sussex, UK.

- De Costa A, Johansson E, Diwan VK. Barriers of mistrust: public and private health osectors’ perceptions of each other in Madhya Pradesh, India. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(6):756–66.

- Barua N, Pandav CS. The allure of the private practitioner: is this the only alternative for the urban poor in India? Indian J Public Health. 2011;55(2):107-14.

- Balarajan Y, Selvaraj S, Subramanian SV. Health care and equity in India. Lancet. 2011;377(9764):505-15.

- Horton R, Das P. Indian health: the path from crisis to progress. Lancet. 2011;377(9761):181-3.

- SatyamevJayate. Does healthcare need healing? Television Series. Star Plus. 2012 [cited 2013 Feb 9]. Available from: http://starplus.startv.in/satyamevjayate/ShowVideo.aspx?videoid=32907.

- Chatterjee P. Trouble at the Medical Council of India. Lancet. 2010;375(9727):1679.

- Chatterjee P. How free healthcare became mired in corruption and murder in a key Indian state. BMJ. 2012;344:e453.

- Dey S. Over 75% of doctors have faced violence at work, study finds. Times of India. 6 May 2015 [cited 2015 May 28]. Available from: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Over-75-of-doctors-have-faced-violence-at-work-study-finds/articleshow/47143806.cms

- Bawaskar HS. Violence against doctors in India. Lancet. 2014;384(9947):955-6.

- Nagral S. Doctors and violence. Indian J Med Ethics. 2001Oct;9(4).

- Mechanic, D. How should hamsters run? Some observations about sufficient patient time in primary care. BMJ. 2001;323(7307):266-8.

- Dibben RM, Lean M. Achieving compliance in chronic illness management: illustrations of trust relationships between physicians and nutrition clinic patients. Health, Risk and Society. 2003;5(3):241-58.

- Van der Schee, E, Bruan B, Calnan M, Schnee M, Groenewegen PP. Public Trust in health care: a comparison of Germany, The Netherlands and England and Wales. Health Policy. 2007;81(1):56-67.

- Rowe R, Calnan M. Trust relations in health care: the new agenda. Eur J Pub Health. 2006;16(1):4-6.

- Sen A. Learning from others. Lancet. 2011;377(9761):200-1.

- Sri BS, Sarojini N, Khanna R. An investigation of maternal deaths following public protests in a tribal district of Madhya Pradesh, central India. Reproductive Health Matters. 2012;20(39):11-20.

- Calnan M,Rowe R. Trust matters in health care. 2008. Open University Press.

- Möllering G. The Trust/Control Duality: An Integrative Perspective on Positive Expectations of Others. Int Sociol. 2005;20:283-305.

- Möllering, G. Trust: Reason, routine and reflexivity. 2006. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Brown P,Calnan M. Trusting on the Edge. 2012; Policy Press.

- Brennan N, Barnes R, Calnan M, Corrigan O, Dieppe P, Entwistle V. Trust in the health-care provider–patient relationship: a systematic mapping review of the evidence base. IntJQualHealth Care. 2013 Dec;25(6):682-8.

- Khodyakov D. Trust as a process: a three-dimensional approach. Sociology. 2007;41(1):115-32.

- Gilson L. Trust and the development of health care as a social institution. SocSciMed. 2003;56:1453-68.

- Gilson L, Palmer N, Schneider H. Trust and health worker performance: exploring a conceptual framework using South African evidence. SocSci Med. 2005;61:1418-29.

- Calnan M, Rowe R. Researching trust relations in health care: conceptual and methodological challenges—an introduction. J Health Organ Manag. 2006;20(5):349-58.

- Connell NA, Mannion R. Conceptualisations of trust in the organisational literature: Some indicators from a complementary perspective. J Health Organ Manag. 2006;20(5):417-33.

- Pilgrim D, Tomasini F, Yassilev I. Examining trust in health care: a multidisciplinary perspective. Palgrave Macmillan; 2011.

- Gopichandran V, Chetlapalli SK. Dimensions and determinants of trust in health care in resource poor settings—a qualitative exploration. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69170. .doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069170

- Gopichandran V, Chetlapalli SK.Factors influencing trust in doctors: a community segmentation strategy for quality improvement in healthcare. BMJOpen. 2013;3:e004115. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004115.

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117.

- Gingrich, A. Conceptualizing Identities. In: Bauman G, Gingrich A, (eds). Grammars of Identity/Alterity–A Structural Approach. Oxford: Berg Hahn; 2004.

- Baidya M, Gopichandran V, Kosalram K. Patient-physician trust among adults of rural Tamil Nadu: A community-based survey. J Postgrad Med. 2014;60:21-6

- Mani MK. Our watchdog sleeps, and will not be awakened. Issues Med Ethics. 1996 Oct-Dec;4(4):105-7.

- Gupta S. Why I returned to the UK. Indian J Med Ethics. 2004 Jan-Mar;1(2):41-2.

- Jesani A. Professional codes, dual loyalties and the spotlight on corruption. Indian J Med Ethics. 2014 Jul-Sep;11(3):134-6.

- The health of India: a future that must be devoid of caste. Lancet. 2014 Nov 29;384(9958):1901. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62261-3.