Abstract

Background: Parents need to be asked to provide informed consent on behalf of their child for participation in genetic research. Decision making for such parents is difficult because ethical challenges in paediatric genetic research studies are different from similar adult studies. This paper focuses on interviews conducted with parents who were asked to consent to their children’s participation (or not) in a genetic research study of intellectual disability and/or autism.Methodology: After oral consent, parents referred to the research team were informed by their treating psychiatrists about the purpose of the study and requested to give written consent. Regardless of their giving or refusing consent to participate, they were requested to participate in an anonymous recorded interview on a specially constructed structured questionnaire regarding their attitude towards genetic studies. Only one of the parents could participate, due to logistic and analytic issues. The study was carried out from*August 2011 to March 2015.

Results: A total of 84 parents completed the interview which was recorded, translated and transcribed. Majority of the parental participants comprehended the elements of informed consent and said that they understood it properly. Nevertheless, 36% opined that if they refused to participate in the research study, it might affect their child’s treatment (the consent form had an explicit paragraph denying this consequence). Thematic analysis was conducted on interview narratives and six themes emerged: research as part of treatment, participation for self-interest, prosocial interest, understanding/not understanding the value of written consent, confidentiality is important/not important, no acceptance of genetic origin.

Discussion: There were varied reasons for participation by parents. While all said that they understood the nature of informed consent, it appeared that they did not fundamentally do so, even though the research team was physically separated from their treating psychiatrist, and only 84/311 referred, had agreed to participate. Though their understanding of genetic issues around their child’s disorder was limited, they still agreed to participate for altruistic reasons. While the individuals in our sample belonged to lower socio-economic groups, they were well aware of the importance of confidentiality in research, the importance of research, and the stigma around the conditions, but trusted the research team because of the government funding source and the government institution where the research was carried out.

Introduction

For several hereditary disorders, genetic testing helps to confirm the diagnosis, serves as a medical monitoring tool, and plays a role in treatment and research (1)). In order for their child to participate in genetic research, parents are asked to provide informed consent. In doing so, they are asked to consider the risks and benefits for their other children as well as for the family. Parents may view these decisions, in their role as decision-maker for their child, somewhat differently from the way they may view such decisions for themselves. Ethical challenges in paediatric genetic research studies are therefore, different from those in similar adult studies.Parents’ attitudes towards genetic testing of their child for research alone need to be examined as they become decision makers for their child’s research participation and genetic testing. Studies have explored why families enrol their children in such research (2) and the ethical implications of including children in genetic studies (3, (4, (5, (6, (7) but not in the Indian public health setting.

Parents consent to participation in such research reveal a variety of motives, which have been reported in several studies on autism. In a survey of parental attitudes towards genetic research procedures of children with autism (N=3539) 1549 parents responded, 83.6% parents were willing to participate in genetic testing and 71.3% stated that it is important to participate in genetic testing to support research on Autism Spectrum Disorder (8). Trottier (9) published a qualitative study on the motivation of families (n=9 age range 39-49 years) for participating in genetic research in autism and expectations arising from this participation. The themes that emerged from the respondents’ interviews were:

• an amalgamation of motives for benefit both to “self” and to “others”

• participation not simply to obtain a genetic research result; but for the value in the act of participating itself, as distinct from the value of genetic information

• expectations of what a genetic result means have evolved with time

Other themes related to self-perceived “scientific” reasons:

• connecting with experts

• the value of having genetic result as related to alleviating guilt

• promoting awareness, increasing acceptance and decreasing judgement

• certainty of genetic research results.

In another study on communicating research results, (158 parents: 89 mothers and 69 fathers with at least one autistic child) (10), 97% of respondents expressed a strong desire to receive research results, either general or individual ones, and a majority of respondents indicated that the research team should take on the responsibility of communicating results. The study reported that 37% of respondents felt the findings, whether favourable or unfavourable, would help them “to be prepared for the future”; 21%, each, felt they would have either “no impact”, or “not necessarily any impact”; while 14% felt they would at least bring relief or understanding.

Causal beliefs about autism (whether genetics or brain abnormality) affected the treatment choices of parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (hereafter, autism). Tabor et al (11) in their qualitative study of parent perspectives on paediatric genetic research participation, and specifically on genotype-driven research recruitment, reported that six out of twenty-three parents had experienced genotype-driven research recruitment and 17 had not. Five themes emerged in their study regarding parents’ perceptions of their children’s research participation:

• avoiding harms,

• time and convenience,

• helping: an opportunity for altruism and positive action,

• “rewards” of research participation, and

• relevance of the study to the family and perceived importance to society.

Comparatively, there is a paucity of research studying attitudes of parents of children with intellectual disability. Murphy and Johnson (2009) reported on attitude towards psychiatric genetic research in discussions among focus groups of African-American parents. The main emerging themes from parents’ participation were: belief in environmental/ childhood upbringing/ early socialisation/ community as a cause of psychiatric disorders, understanding of genetics as traits that are passed down from parents to children/ superficial knowledge of terminology as DNA, RNA and so on (12).

Our study focuses on interviews conducted with parents asked to consent or refuse the participation of their children in a genetic research study of either intellectual disability or autism. The other arm of the research study included asking parents to participate in psychoeducation sessions for dealing with their child’s day to day issues. The third arm, on attitudinal questions, focussed on understanding how parents make decisions about enrolling their children in genetic research and what they think about genetic research. Both consenting and non-consenting parents answered questions on what determined their decision. This was important for developing effective and appropriate approaches for children’s research recruitment in genetic studies.

Methodology This study formed a part of the project “Effect of Parental Psycho Education, Ethics of Research Participation, and Array Comparative Genomic Hybridisation in Subjects with Mental Retardation (MR/ID) and/or Autism”, funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India.

The first arm of the study was to evaluate children with intellectual disability/ mental retardation (ID) and autism using whole genome Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (CGH) and to identify novel microdeletion/micro duplication syndromes. The second arm was to examine parental attitudes to participation in genetic studies; and the third was to develop a psychoeducation module for parents. All three arms of the study were independent of each other. Thus, parents could agree to their child’s and their own participation in one, two or all three arms of the study, or refuse.

Children between 3-18 years (and their parents) were eligible. Permission to carry out the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Atal Bihari Vajpayee Institute of Medical Sciences (formerly PGIMER) and Dr RM Lohia Hospital, and the Centre for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics (CDFD, Hyderabad) where array CGH was carried out. The study was carried out from August 2011 to March 2015 at the Department. of Psychiatry, PGIMER. Dr RML Hospital.

The children and their parents were informed about the study by their treating psychiatrists and asked if they would like to participate. The parents were informed about the three arms of the study, and expressed interest in participation by providing oral consent. The interested parents were then asked to approach the research team (which worked from a separate room in the same complex) where they were explained the details of the study and written consent was obtained if they agreed.

A structured Hindi questionnaire (Table 2) was developed to understand the reasons for agreeing/refusing their child/ren’s participation in the study, parental understanding about informed consent, genetic illness, genetic studies and attitude toward genetic studies. It consisted of 11 questions. The questionnaire consisted of questions that required “yes” or “no”, answers and then the parent was asked to explain their choice. A longer, non-directed interview was not planned as participation entailed other time-consuming procedures, and non-consenting parents were willing to give still less time for the interview. Even if both parents were present, due to logistical issues about recording, they were requested to have only one of the parents respond to the interview. Sometimes, the other parent, if present, intervened and clarified the answer.

All parents were asked for their consent to be interviewed, as well as for its recording (arm 3). If they refused the participation of their child/ren in the genetic study (arm 1), they were nevertheless informed about the questionnaire and themselves requested to participate in the parental attitudinal interview (arm 3). All interviews were recorded anonymously. All were in Hindi as the original questionnaire had been developed in Hindi. These narratives were transcribed by research personnel and then translated. Codes were extracted from these translated narratives. Thematic analysis in which collected narratives and analyses were integrated with the interview guides was conducted for extracting themes.

Data analysis

All translations were analysed by members of the research team, all of whom happened to be clinical psychologists and psychiatric social workers. Frequencies of all answers as affirmative and negative were calculated. Qualitative data were coded by one researcher into rough codes with longer text. After the first stage of simple coding, codes with similar content were clubbed together into higher order codes. A third researcher checked the third order codes after rereading the entire narrative (for inter-rater reliability). Interview responses were systematically analysed to identify responses grouped around common themes, reflecting interviewees’ perspectives, understanding, concerns, and interests. We examined parents’ responses to specific questions related to their reasons for research participation, their perceptions about the risks and benefits of receiving individual genetic research results, and their understanding of the goals of the research.Results

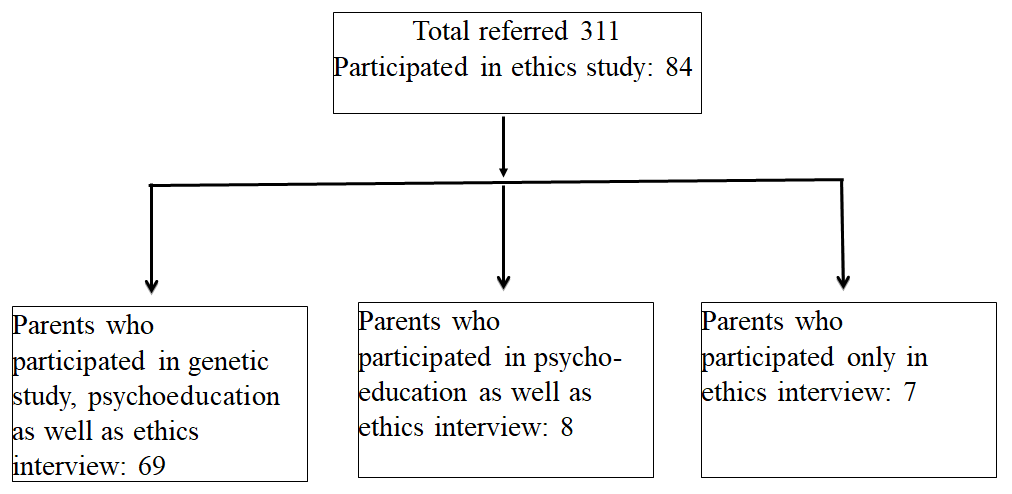

Participants A total of 311 children with autism or ID, with accompanying parents, were referred for participation in the study. Only 90 parents, aged between 25 years to 59 years, consented to their child/ren’s participation in the genetic study. However, all parents did not have time to participate in the interview or the psycho-education session. Out of 90, 69 agreed to participate in the genetic study as well as ethics interview. In addition, 15 parents who refused to participate in the genetic study, did participate in the ethics interview.Figure 1. Flowchart of recruitment:

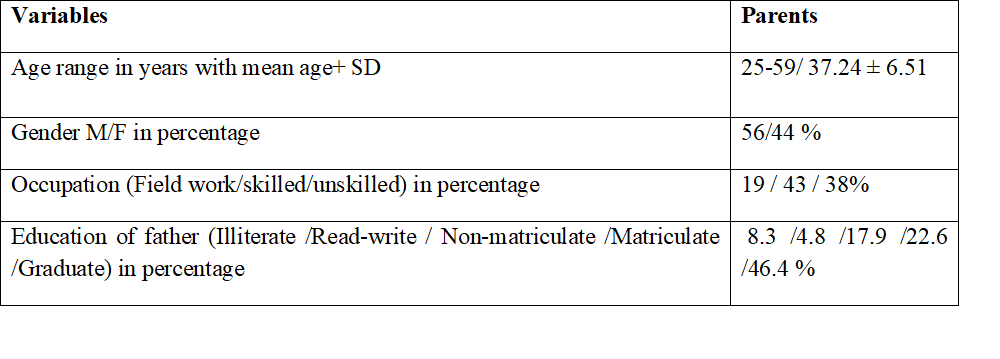

Table 1: Demographic details of the sample (n=84)

Quantitative analysis

Out of 90, 15 (16.66%) refused to participate in the genetics arm of the study but agreed to participate in the ethics interview. Among those who answered, most parents were middle aged, and slightly more than half (56%) were fathers. A large group (46.4%) were graduates but the overwhelming majority (81%) worked as skilled or unskilled labour and thus, a majority belonged to lower socio-economic groups (Table 1). The sample was large enough (84) for the interview.

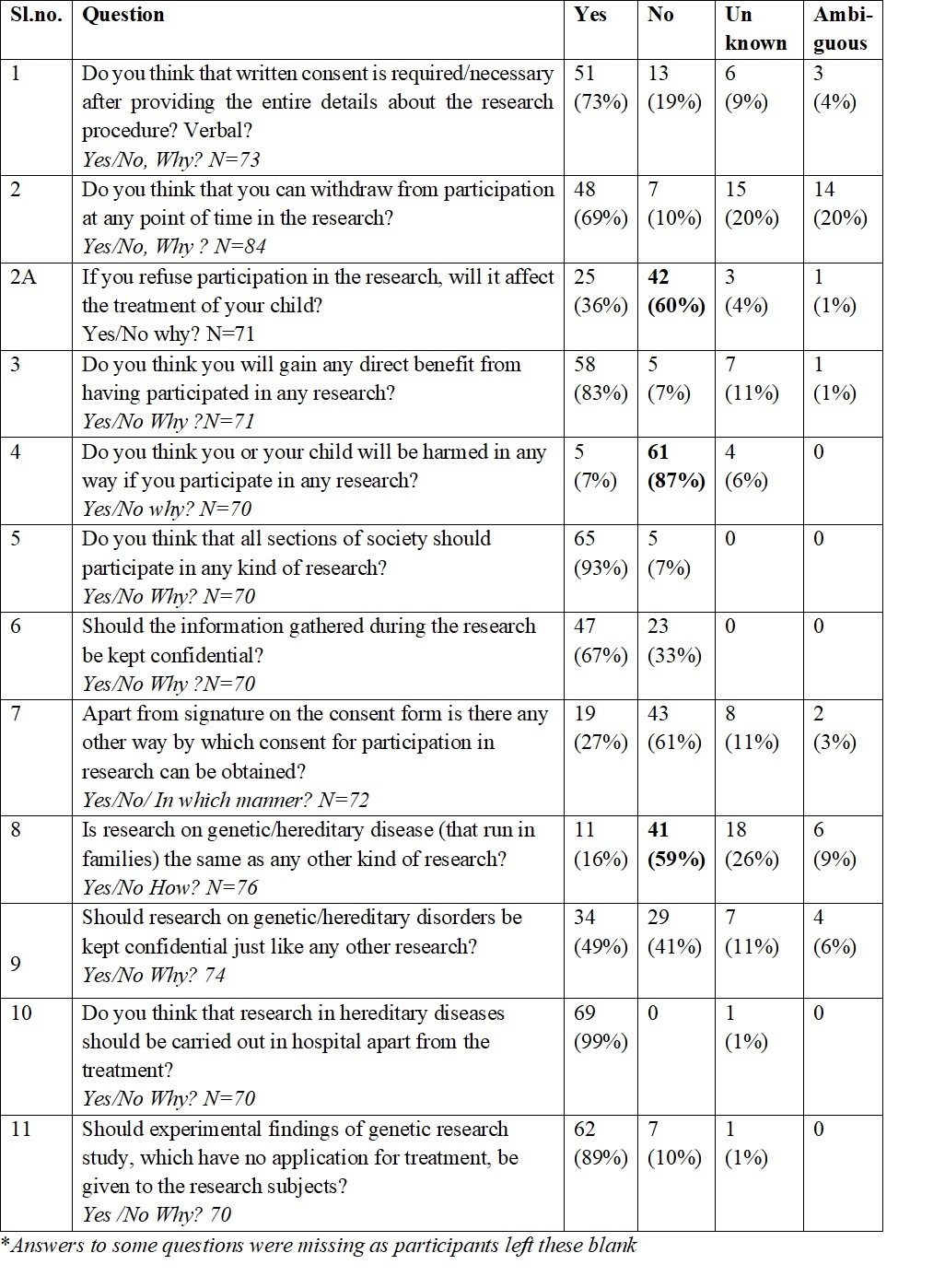

On most of the questions of the interview (Table 2), a majority of the participants understood the elements of informed consent and answered in the affirmative. Nevertheless, there were certain discrepancies in their answers. While 87% of parents agreed that their child would NOT be harmed in any way in genetic research, 83% felt they would gain directly from the study; 69% understood that they could withdraw from the study at any time, yet 36% opined that if they refused to participate in the research study, it might affect their child’s treatment. Half ie 50%, were not sure if they could withdraw from the study at any time (the interviewer had cleared this issue before obtaining written informed consent). Regarding confidentiality, the majority agreed that the research data should be kept confidential; and 67% felt that confidentiality of the research data was important.

Table 2: Frequencies and percentages* of replies to the ethics questionnaire:

Thematic analysis

The following themes emerged from the narratives of participants in reply to questions:

(i) Research as part of treatment

Parents perceived research as a part of the government’s initiative to frame policies that would combat problems faced by children with ID / Autism. They complained that, at present, there were very few training centres, schools, rehabilitation centres and trained professionals available in government hospitals. In addition, the available facilities were very expensive. Others believed that research was important for creating awareness programmes. On asking whether they would like to withdraw from participation at any point of time, one parent replied that they would never withdraw because they would not like to keep the “treatment” incomplete.

(ii) Participation for self-interest (the benefit of “self”)

Parents thought their interests would be served by participating. For instance: “We are taught to teach the children in such a way that we can apply that. For that if we go for some other training then we will have to spend a lot of money” (888021-021). Regarding psycho-education, the parent shared the expectation from such training “…through it (research participation), whatever we are getting to know will be getting knowledge …. well-being of our child will be there and then even parents will also get to know about how to take care of the child, so in my opinion, participation is very important…”(777057-065). They were also motivated by the genetic testing being free of cost, as these tests are very expensive at private laboratories. In the words of one of the participants “We can show the blood report to any doctor, and if there is any medical benefit, we will be able to avail it.” (777024-028). Some also thought that by participating in the research project, the child’s intelligence would improve. Some thought that the research would be useful for the prevention of genetic illness.

(iii) Prosocial interest (benefit of “others”)

Parents also participated for the welfare of society and science. A participant mentioned that “We are always ready to participate in research that benefits people, whatever research it is” (777024). Many parents believed that every section of society should be involved in research for better results and “standard” research. Some parents wanted to involve all sections of society in research. One participant said that “Absolutely every section should be involved… because research is about data collection… there will not be one sided result… if there is only one type of section who take interest in research then result could be affected, it will defeat the purpose of the research” (777035-039). This also showed a degree of research sophistication. Participation in research would be useful for prevention of genetic illness, new methods of precautionary measures could be developed before planning the family: that “… whatever experiment you are doing should get proper results on time so that in future there is no problem, it can be beneficial to other children…..so that people will know what are the problems during pregnancy and if taken care can be useful for healthy children” (777048-055). Some respondents hoped that research would benefit the next generation. Some participants did not want to keep the results of genetic research confidential so as to benefit others, who could be informed about illness and treatment and go in for treatment early. Parents were motivated by both self-interest and societal benefits at the same time.

(iv) Understanding/not understanding the value of written consent

Parents wanted written consent forms, so that, in case they faced any problem during participation in research, the consent form could be used as proof. Also, this evidence of their responsibility towards research and thus, their “authenticity”, was useful for research procedures, documentation and legal use. Some parents anticipated that if they found any improvement in their children, they might use the written consent documents as a reference to spread this information to similarly placed parents for use. A few participants considered the consent form as proof of research, it provided details of the research, usage of information and authenticity of the study. Others believed that written consent was important because it can be an identity proof for permission to ‘enter the department’ (erroneous belief). A few parents expressed the thought that trust in the hospital was more important than written or verbal consent “I think the best thing is a trust between the doctor and the patient/parents also…… This written consent is not mutual consent. I think mutual consent is moreover trust… best thing is we should believe in the doctor…. It will benefit both child and is for betterment of child…” (777057-065). When we asked for suggestions for improvement in the consent process, the main suggestions were: maintaining photographs or audio/video recordings as proof of consent, and distributing leaflets to increase the participants’ understanding of research. They also suggested that participants should be given time to discuss with their relatives and others before giving consent (they should be allowed to take the form home) (which they are told as a matter of course).

(v) Importance/or not of confidentiality

Parents wanted confidentiality, with information to be shared with doctors only. Disclosing the genetic origin of illness would affect the status of the whole family: “entire family will be impacted, so it should remain hidden as a fundamental right” (777035-039). One important theme that emerged was the discrimination in society if others came to know about the illness…. “Our child is abnormal so we think ok does not matter, but others with normal children may not allow him/her to mingle in society or in school as they (other children) may learn bad habits like scratching, biting etc. from our kids” (999006-006). They perceived that the future and career of the child was also impacted. One of the parents commented that if there was a chance of breach in confidentiality, he would not allow participation as there could be career problems in future. Marriage – even for others in the family- was also an important reason to keep the information confidential. Another set of parents thought that there was no need to keep their diagnosis and research participation confidential. They felt that by participating in research they were not doing anything against the norms, so there was no need for secrecy. Some parents wanted the knowledge to be made public, so that others were benefitted. An option probed for ways to decrease stigma and increase awareness was: “you should not keep it secret …. And if someone suffers from the same disease then people can tell to bring the patient to that hospital and doctor.” (888004-004). Genetic results should be published in a way that while the main theme was published, it should not be mentioned that the illness was transferred from father and mother.

(vi) Denial of genetic origin

This last theme was quite surprising to us as many parents had already attended NGO or special school services and had been referred to Dr RML Hospital for evaluation and assessment of their child. The majority of parents had no idea about genetic research. Some parents offered to withdraw if sensitive questions regarding the child and the family were asked. The verbatim response was “Yes, if we are forced to answer too sensitive questions then we should be allowed to withdraw at any point of time” Also “my child should not be harmed. Sensitive questions may hurt…” (777042-049). Genetic results should be published without any identifiers (confidentiality above). The family origin of that genetic research should not be mentioned in the consent form. Most parents believed consent was important before publishing the research data with identifiers. A few gave suggestions for improving research procedures. Income being a sensitive issue should not be included.

Discussion

Genetic studies are an important part of human biological research. Children should not be deprived of the benefits of research into diseases that are manifested in childhood. However parental consent is essential in these cases. Obtaining written informed consent from prospective research participants is the most important aspect of a research study. It is even more important when vulnerable participants are involved (children, the poor, and those recruited for genetic studies) (13), Prospective participants in genetic research may consent without fully understanding the information provided for informed consent, for reasons such as more frequent contact with the research team, or unknown reasons like poor recall of why they consented initially, or refuse due to social stigma (14, (15, 16).Ours was a sample from a free government treatment facility. Parents had approached or were referred to the facility for diagnosis and management of their child or children with ID or autism. Ours was a relatively low socioeconomic and lower education group. Parents probably believed they would receive additional attention or care by participating in research (since the larger research project promised genetic testing as well as psychoeducation), which they could not afford at private facilities. Parents could understand issues around genetic testing. Their consenting or otherwise was determined by social, economic or environmental factors. Participation in research needed extra time and effort, which the majority could not afford. Although they were poor, and viewed the government institution as their last resort, they considered all factors before consenting.

Nevertheless, only socio-economic factors may not determine who agrees or refuses to participate, other factors may be equally important. In our study, 15/84 parents refused to participate in the genetics arm yet participated in the interview. In a cohort study in Pune, illiteracy was the only reason for non-comprehension of consent information (17). In our own sample, a majority of the fathers were educated up to graduation level, but unfortunately, the educational level of the mothers was not obtained. In a low literacy setting in South India, only 13% of parents asked questions in an observational study for their infants, questioning was related to their education level and presence of both parents during the informed consent discussion (18). In a large American epidemiologic catchment area study for genetic testing and storage, only younger age (agreed to genetic testing), race (disadvantaged participants refused storage of genetic samples for future research), and positive family history (agreed to testing) were related to willingness to participate in genetic studies (83% of 1,071 prospective participants in 2004-2005 agreed, the rest refused)( 19). In a second American study, younger age, male gender, and African-American ethnicity was associated with refusal to participate in a study on genetic risk for atherosclerosis (20). Another Indian study reported that education and socio-economic status were not related to comprehension of research procedures in a clinical trial, provided the information was presented in simple language (21). From the literature and from our own study findings, it appears that comprehension and consent are determined by multiple factors, but education, perhaps reflecting cognitive ability, may be the most important. Information should be presented, and discussed in simple language and participants must be given the opportunity to take the consent form home and discuss participation with close relatives or important others.

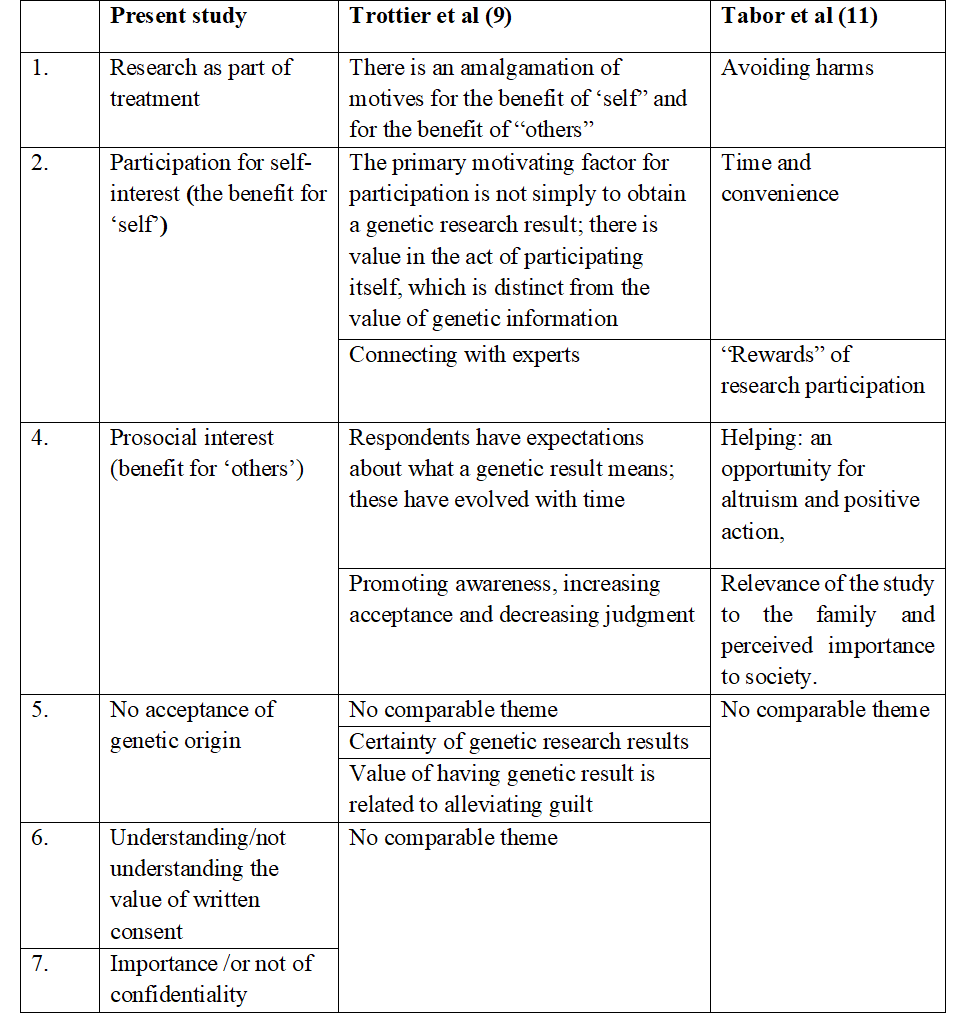

Although our parents came from poorer backgrounds, many fathers were educated and, as seen from some of the verbatim quotes above, were aware of situational issues and their rights. Parents answered questions fully in the qualitative interview. However, some literate parents did leave questions blank in the yes/no questionnaire handed to them (Table 2) and did not venture answers even in the spoken interview. Interviews were carried out by personnel who were not involved in the other parts of the research. It was felt that this would help parents to answer our questionnaire more freely and honestly. Two earlier papers describing attitudes of parents’ consent to their child’s participation in research studies reported some similar themes (summarised in Table 3). However, since we had specifically asked about informed consent and confidentiality, different themes also emerged in our study.

Table 3: Comparison of our themes with other studies

Themes revealed some of the participants’ naiveté about genetic research, awareness of social stigma attached to such illnesses, and the consequences of loss of confidentiality. Only a minority felt that trust in the doctor and mutual consent was enough, while most wanted to use their copy of the consent form document for future benefits for themselves and their child. Although a socially disadvantaged group, they did not feel at a disadvantage with the research system and could hold their own in it. It should also be noted that a very small minority of parents consented to participate in genetics (90/311 referred); and a still smaller number, 84, participated in the interview. It is presumed that those who refused, were broadly similar in socioeconomic factors to those who consented. However, for a qualitative study this sample was felt to be adequate.

Since the research was funded by the government and conducted in a government hospital, they felt it was a special programme for poor people to help/cure the affected children, to create awareness in society, to reduce discrimination as well as enhance participation in research. Participants were referred to research personnel by their treating doctors, so one of the overarching themes was that research was part of the treatment package itself and would address the complaints/treatment for which they had sought consultation. This is in accordance with the theme “connecting with experts”( 9) and of parents expecting rewards for research participation (22) (participating for self-interest‒ our second theme). Three main reasons were given for positive attitudes towards genetic testing by 42 parents of autistic children: early intervention and treatment, identifying the aetiology of autism, and informed family planning (23). In addition, parents trusted their treating psychiatrist and tended to agree to their doctor’s suggestion for research participation.

However only a minority of parents, among those who approached the research staff participated (only 84/311). Trust is a fundamental part of the doctor-patient relationship and health outcomes are determined, to some extent, by trust in the doctor (24). The doctor patient relationship may be considered paternalistic and some patients may find it difficult to say “no”. Thus, the decision to participate in research may have been influenced to some extent by their treating psychiatrist introducing the topic to them. Yet, psychiatrists are generally less paternalistic than other doctors (25). Only a small group of parents (25/311 of the total referred) were apprehensive that their nonparticipation might affect their relationship with their doctor and the treatment of their child. In our consent form, it was clearly emphasised that non-participation in research would not affect treatment in any way, and that the research itself was not of any immediate benefit to the child. This accounts for the fact that of the large number of parents referred to the research, only a small number actually participated (84/311).

Some parents consented for personal benefit. They could avail the advantages of services offered as part of the research, like behaviour therapy, psychoeducation, and parental training which are quite expensive otherwise. This is in accordance with the Trottier (9) theme of the benefit for “self”. In the Johannessen (8) study, 63.7% parents said they would participate for better treatment (self-interest) while 25.6% believed that genetic data was irrelevant for interventions. Johannessen (8) found that the parents of children with infantile autism were more positive toward genetic research and procedures of research. But others participated out of altruism ‒ they did not want other parents to face what they were facing. Parents in our study were fully aware of the stigma they themselves, and their child, would face if news of their participation got out through publications. Hence, they were insistent on confidentiality, both for their own sake and for the sake of the entire family, their children’s marriage prospects (a very important issue in India) and career. Since some children had behavioural issues (scratching, biting etc) the parents felt that other parents would isolate their child if they found out his/her condition.

As for written consent, parents did agree with the need for written consent but for unexpected reasons, one of them being that they could use the form as an identity proof for various legal purposes and even for accessing services in the future. Others wanted to use the information in the consent form ‒ and their participation ‒ to inform other parents of illness-related scientific issues. This again brings forward the altruism theme. A minority of parents thought “trust” in the hospital and belief in the doctor was more important. Several suggested photographs, audio or video recordings as proof of consent. Some parents felt “too sensitive” questions should not be asked in research and that they would refuse to answer, if asked. They felt all personal information should be kept strictly confidential. Surprisingly, some parents simply denied the presence of ID/autism in their child. This was the reason for their non-participation. Others felt that the illness was not genetic, did not run in families. But if research proved to the contrary, then they would face stigma and so, it was better not to participate. It was difficult for them to accept the genetic origin of the disease as this could lead to feelings of guilt and family conflicts. Psycho-education regarding genetic origins might help the parents to understand the illness and help them face the challenge with behavioural treatments.

Conclusions

In a free government hospital, 71% of referred parents did not consent to their own participation (for psychoeducation) or that of their affected child (for genetic research). Only 29% of referred parents (N=84) agreed to participate in a brief interview about attitudes to research participation. Among those who agreed, confidentiality was an important issue. They were wary of societal stigma regarding their child’s condition. Yet, many were hopeful that research would yield valuable benefits, some misperceived research as part of treatment, and still others participated for societal benefit.In conclusion, differing attitudes and circumstances determine parents’ consent to their child’s participation in genetic research. Attitudes ranged from selfless altruism to research for scientific answers, taking advantage of research as treatment services for themselves and their child, to even a blind denial of familial/genetic origins in order to reduce social stigma. When planning research, and preparing a consent form, these issues must be kept in mind. Consent forms should be simple, open about methods and aims, and must emphasise confidentiality. Finally, participants have to be informed of the intent of the study to the fullest extent.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have any conflict of interest to declare.Funding source

The project was funded by the ‘Tri National Training Program in Psychiatric Genetics’ #D43TW008302 from the Fogarty International Center, NIH, USA to Dr V L Nimgaonkar and Dr S N Deshpande. Funding was also awarded to Dr SN Deshpande for the project ‘Effect of Parental Psycho Education, Ethics of Research Participation, and Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization in Subjects with Mental Retardation (MR) and/or Autism’ by the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH or the DST. The Fogarty International Center, NIH or the DST had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.References

- McPherson E. Genetic diagnosis and testing in clinical practice. Clin Med Res. 2006 Jun;4(2):123-9.

- Bernhardt BA, Tambor ES, Fraser G, Wissow LS, Geller G. Parents’ and children’s attitudes toward the enrollment of minors in genetic susceptibility research: implications for informed consent. Am J Med Genet A. 2003 Feb;116A(4):315-23.

- Gurwitz D, Fortier I, Lunshof JE, Knoppers BM. Research ethics. Children and population biobanks. Science. 2009 Aug 14;325(5942):818-9.

- Hens K, Nys H, Cassiman JJ, Dierickx K. Genetic research on stored tissue samples from minors: a systematic review of the ethical literature. Am J Med Genet A. 2009 Oct;149A(10):2346-58.

- Hens K, Nys H, Cassiman JJ, Dierickx K. Biological sample collections from minors for genetic research: a systematic review of guidelines and position papers. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009 Aug;17(8):979-90.

- Hens K, Cassiman JJ, Nys H, Dierickx K. Children, biobanks and the scope of parental consent. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011 Jul;19(7):735-9.

- Kaufman D, Geller G, Leroy L, Murphy J, Scott J, Hudson K. Ethical implications of including children in a large biobank for genetic-epidemiologic research: a qualitative study of public opinion. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2008 Feb 15;148C(1):31-9.

- Johannessen J, Nærland T, Bloss C, Rietschel M, Strohmaier J, Gjevik E, Heiberg A, Djurovic S, Andreassen OA. Parents’ attitudes toward genetic research in autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatr Genet. 2016;26(2):74-80.

- Trottier M, Roberts W, Drmic I, Scherer SW, Weksberg R, Cytrynbaum C, Chitayat D, Shuman C, Miller FA. Parents’ perspectives on participating in genetic research in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013 Mar;43(3):556-68.

- Baret L, Godard B. Opinions and intentions of parents of an autistic child toward genetic research results: two typical profiles. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011 Nov;19(11):1127-32.

- Tabor HK, Brazg T, Crouch J, Namey EE, Fullerton SM, Beskow LM, Wilfond BS. Parent perspectives on pediatric genetic research and implications for genotype-driven research recruitment. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2011 Dec;6(4):41-52.

- Murphy E, Thompson A. An exploration of attitudes among black Americans towards psychiatric genetic research. Psychiatry. 2009 Summer;72(2):177-94.

- . Mathur R, editor. National Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical and Health Research Involving Human Participants. New Delhi: Director-General Indian Council of Medical Research; 2017.

- Rose D, Russo J, Wykes T. Taking part in a pharmacogenetic clinical trial: assessment of trial participants understanding of information disclosed during the informed consent process. BMC Med Ethics. 2013 Sep;14:34.

- D’Abramo F, Schildmann J, Vollmann J. Research participants’ perceptions and views on consent for biobank research: a review of empirical data and ethical analysis. BMC Med Ethics. 2015 Sep 9;16:60.

- Tekola F, Bull S, Farsides B, Newport MJ, Adeyemo A, Rotimi CN, Davey G. Impact of social stigma on the process of obtaining informed consent for genetic research on podoconiosis: a qualitative study. BMC Med Ethics. 2009 Aug 22;10:13.

- Joglekar NS, Deshpande SS, Sahay S, Ghate MV, Bollinger RC, Mehendale SM. Correlates of lower comprehension of informed consent among participants enrolled in a cohort study in Pune, India. Int Health. 2013 Mar;5(1):64-71.

- Rajaraman D, Jesuraj N, Geiter L, Bennett S, Grewal HM, Vaz M, TB Trials Study Group +Collaborators.. How participatory is parental consent in low literacy rural settings in low income countries? Lessons learned from a community based study of infants in South India. BMC Med Ethics. 2011 Feb 15;12:3.

- Mezuk B, Eaton WW, Zandi P. Participant characteristics that influence consent for genetic research in a population-based survey: the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area follow-up. Community Genet. 2008;11(3):171-8.

- Green D, Cushman M, Dermond N, Johnson EA, Castro C, Arnett D, Hill J, Manolio TA.. Obtaining informed consent for genetic studies: The multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2006 Nov 1;164(9):845-51.

- Bhansali S, Shafiq N, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, Singh I, Venkateshan SP, Siddhu S, Sharma YP, Talwar KK. Evaluation of the ability of clinical research participants to comprehend informed consent form. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009 Sep;30(5):427-30.

- Taber LH, Frank AL, Yow MD, Bagley A. Acquisition of cytomegaloviral infections in families with young children: a serological study. J Infect Dis. 1985 May;151(5):948-52.

- Chen LS, Xu L, Huang TY, Dhar SU. Autism genetic testing: a qualitative study of awareness, attitudes, and experiences among parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Genet Med. 2013 Apr;15(4):274-81.

- Birkhäuer J, Gaab J, Kossowsky J, Hasler S, Krummenacher P, Werner C, Gerger H. Trust in the health care professional and health outcome: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017 Feb 7;12(2):e0170988.

- Falkum E, Førde R. Paternalism, patient autonomy, and moral deliberation in the physician-patient relationship. Attitudes among Norwegian physicians. Soc Sci Med. 2001 Jan;52(2):239-48.