ARTICLES

The making of a “Citizen Doctor”: How effective are value-based classes?

Radhika Hegde; Manjulika Vaz

Published online on May 12, 2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2020.055Abstract

In 2018, the Division of Health and Humanities at St John’s Research Institute introduced the “Citizen Doctor” course for first year medical students at St. John’s Medical College. The focus was to expose future doctors to the wider framework of health and invoke a sense of citizenship, responsiveness, and critical thinking. Classes in Environmental Sciences and the Constitution of India, advocated as beneficial for all undergraduate students in India, were used as the basis to design the Citizen Doctor Course. This paper is an evaluation of this innovative course. A structured feedback questionnaire was administered to students at the end of the course; an overwhelming majority found that these classes helped them identify and understand contemporary social and environmental issues. It evoked a sense of wider responsibility and responsiveness, thus laying the foundation for a “citizen doctor”. The evidence suggests that this course should continue and expand to other years and other medical collegesKeywords: Citizen, humanities, environmental science, constitution of India, social determinants of health, medical education

Introduction

Medical education in India has traditionally focused on providing technical expertise to doctors. The logical inquiry-based learning of asking more to understand more is quintessentially absent in our medical education today (1). Concerns have been raised about the lack of sensitivity and compassion of young medical doctors in India due to excessive stress on objectivity (2), triggering a discussion on the inclusion of the humanities in the medical curriculum (3), so that they can better serve the wider social needs of the underserved in rural areas (4,5). The Bhore Committee in 1947 emphasised the need to develop the social character of the physician: “protecting the people and guiding them to a healthier and happier life” (6).

The success of a democracy depends on its active citizenry. A proactive citizen engages in debate, participates in the legislative processes, and encourages the disempowered to be a part of the democratic structures in order to promote inclusion (7). As Habermas notes, “the institutions of constitutional freedom are only worth as much as a population makes of them” (8). While attempting to address public health needs, doctors need to realise that they are an integral part of the society and the environment in which they live. In a hugely diverse and disparate country like India, doctors, because of their privileged role in society, are uniquely placed to play a prominent public role. Specific actions that doctors can undertake include promoting a cleaner and healthier environment, addressing the social determinants of health, and being advocates for social justice and better health laws. In order to do this, however, doctors need to see their role evolving from a doctor to that of a responsive “citizen doctor”.

Rapid economic and technological progress has fueled economic growth but has also led to ecological disturbances and has widened social inequalities. It is only through environmental education that pro-environmental behavioural changes can be brought about (9). An understanding of environmental issues will enable medical students to adopt values and goals to engage as citizens in crucial issues related to the environment. This is all the more important if medical students are to value the social determinants of health, of which environmental/ecological issues are an important part.

Studies have shown that incorporating interdisciplinary knowledge and the use of pedagogic methodology like reflection in medical education improves critical thinking and diagnostic reasoning of complex and unusual clinical cases (10, 11). At St. John’s Medical College, Bangalore, 20 hours are devoted to Environmental Science (ES) and the Constitution of India (CI) for first year MBBS students. Although not a part of the formal medical curriculum, these subjects have been advocated for first year undergraduate students (12, 13). In 2018, the Division of Health and Humanities redesigned these classes as the Citizen Doctor Course. Although, there is an ongoing discussion in India on educating future doctors to be more socially responsible citizens, there has been little attempt at making the professional and civic duties of the doctor complementary to one another. The Citizen Doctor Course is unique to St Johns Medical College. It was designed with a purposeful shift from providing knowledge to inspiring and initiating responsiveness and critical thinking among medical students. The citizen doctor fosters the idea of a “Civic-Minded Professional” (14) in whom the professional duties of the doctor and her/his civic responsibilities are interrelated. Political theorist Iris Marion Young in her treatise Justice and the politics of difference (15) decries the reduction of social justice and suggests inclusive, participatory ways of bringing about change in society. She brings to the fore the idea of “differentiated citizenship” where individuals can be segregated and considered different due to their social and locational grouping, but where the critical requirement is to recognise the value of responding to the needs of society and being “together in difference” (16).

Exposing students to the citizen doctor classes in the first year of medicine is ideal, as they have unbiased minds as well as the curiosity to learn. The classes were structured around two core values:

1. The importance of human rights, human dignity, public advocacy, and solidarity with social issues and marginalised people;

2. A sense of responsibility for one’s actions and a sense of responsiveness to inter-connected problemsThis paper evaluates the Citizen Doctor course through feedback received from the medical students.

Methods

The study was conducted in a private Catholic Minority Medical College in Bengaluru City, Karnataka, which has a specific mission to train doctors to work in underserved areas. The majority of the students are Catholic, including 20 nuns. Students are drawn from various states, including 30 students from states with particular health needs in North and Northeast India. A little less than two-thirds of the students in the last three years have been women. Every year, the first-year students attend CI and ES classes mandated by the Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences. Students also go through a compulsory ethics training course throughout their medical education (17).

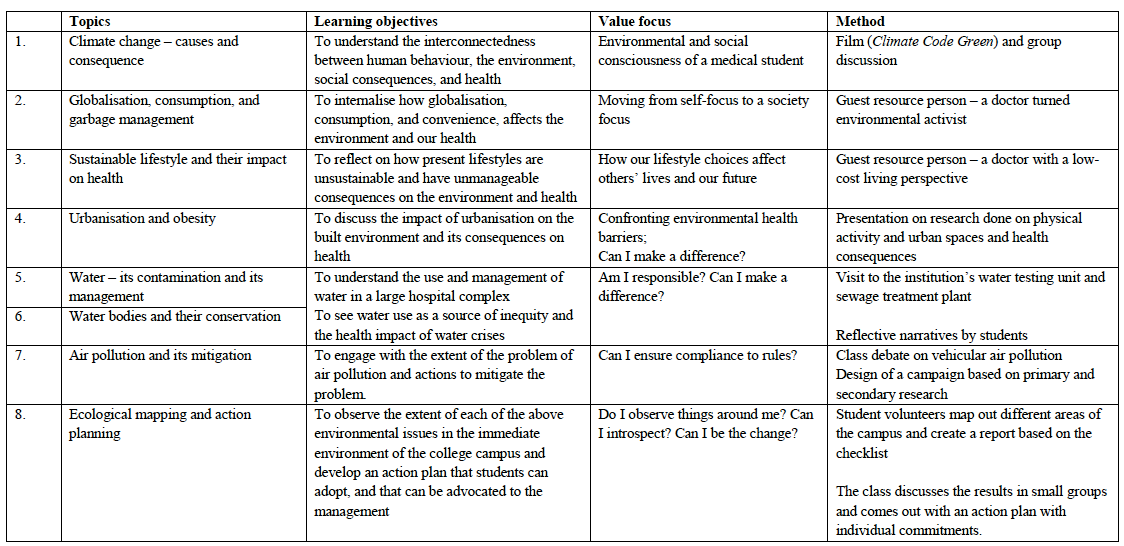

The ES Course classes of the Citizen Doctor course covered topics ranging from climate change – including causes and consequences, globalisation, consumption and garbage management, sustainable lifestyles and its impact on health – to specific issues such as water bodies and their conservation and air pollution and its mitigation. A central value focus in these classes was “Am I responsible? Can I make a difference?” Table 1 provides the structure of the ES course. There were seven contact classes, two classes involving fieldwork, and one class for presentations.

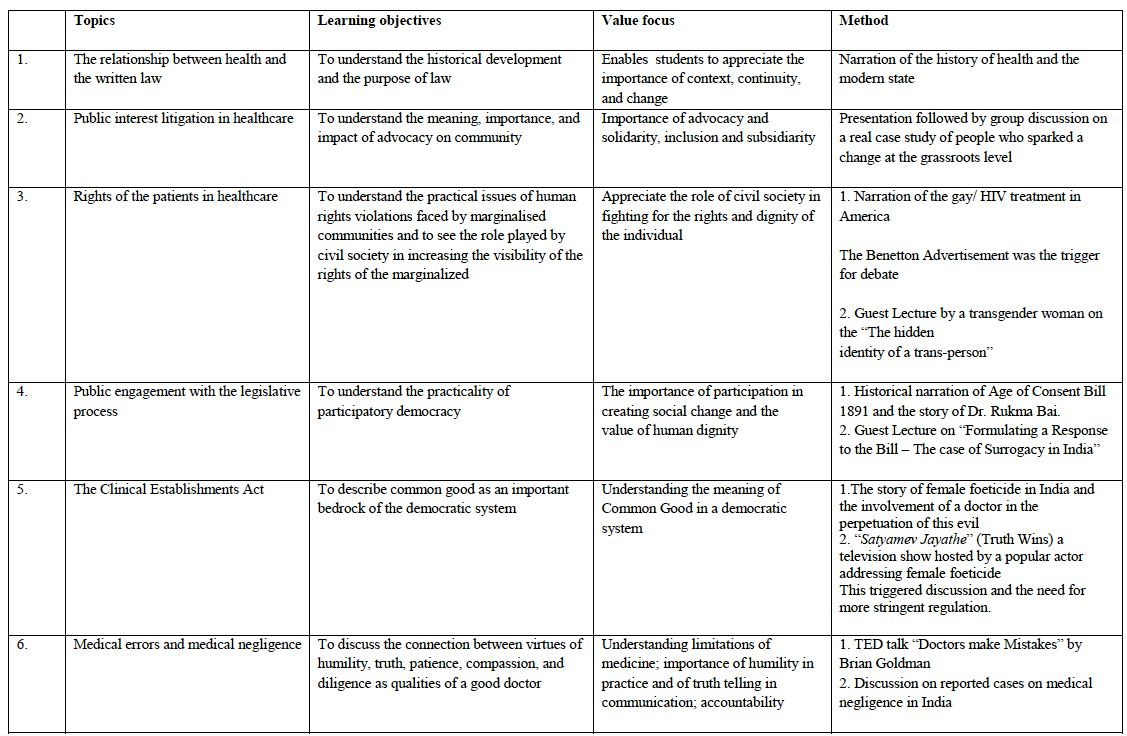

The CI classes were focused on the understanding of the role of a citizen doctor and the civic responsibility towards the community and the state. The topics chosen for discussion were patient rights, public engagement with the legislative process, the Clinical Establishments Act, and medical errors/medical negligence. A central value focus was ‘Can I be an agent of change in communities and society?’ The sessions were provocative by design, aimed at encouraging critical thinking amongst the students. Table 2 provides the structure of the CI Course. There were 10 contact classes.

Teaching–learning aids, like short video clippings and activities such as reflective writing, supplemented the traditional lecture method. Guest speakers were invited to share their experiences on responding to contentious and pressing social issues.

The feedback evaluation process

One hundred and fifty first year undergraduate students of a single medical college (where the authors work) attended this course. On the last day of the course, feedback was received through a semi-structured questionnaire that was administered to the students. Most of the questions were brief with responses on a five-point Likert scale; these addressed the perceptions of need and usefulness of the course, feedback on the coverage and methods of teaching, and suggestions for improvement. The questionnaire had gender and age information but was anonymised, with no requirements for individual names. There were some open-ended questions. The study protocol was submitted to the Institutional Ethics Committee (Ref No 240/2018) but was cleared as exempt from ethics approval as this was an evaluation of a course in an educational institution. No individual consenting process was required.

Data was entered and analysed using Microsoft Excel (Office 365). The investigators manually analysed the open-ended questions following thematic content analysis. Responses were either quoted verbatim or were paraphrased by the authors. The responses quoted verbatim have been put in inverted commas in the results.

Table 1: Work plan of the Citizen Doctor – ES course

Table 2: Work plan of the Citizen Doctor – CI course

Results

One hundred and fifteen out of 150 students, and 96 out of 150 students, provided feedback for the ES classes and CI classes of the Citizen Doctor course, respectively. This was slightly less than the average attendance of both the ES and CI classes over the term (121/150 and 102 /150, respectively.)

Of the 115 students who answered the ES survey, 80 were girls, 30 were boys; 5 students abstained from identifying their gender. Of the 96 students who answered the CI survey, 69 were girls, 24 were boys; 3 abstained. 75% of students were between 18 and19 years of age, 19% were between 20 and 23 years with seven non-responders.

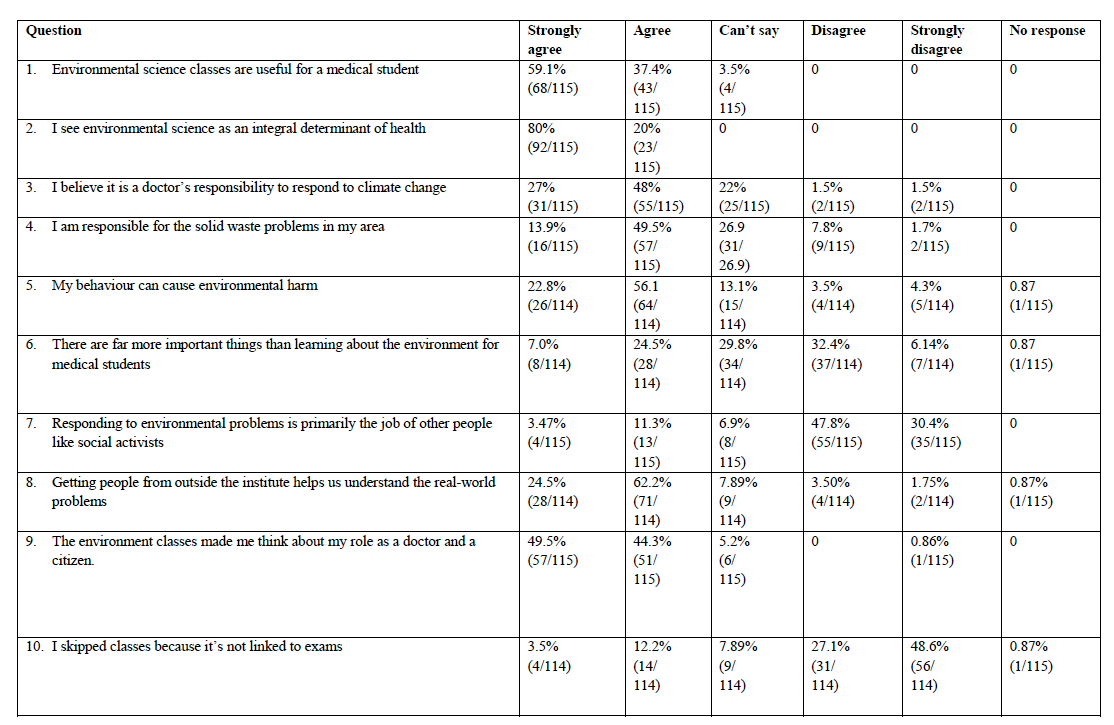

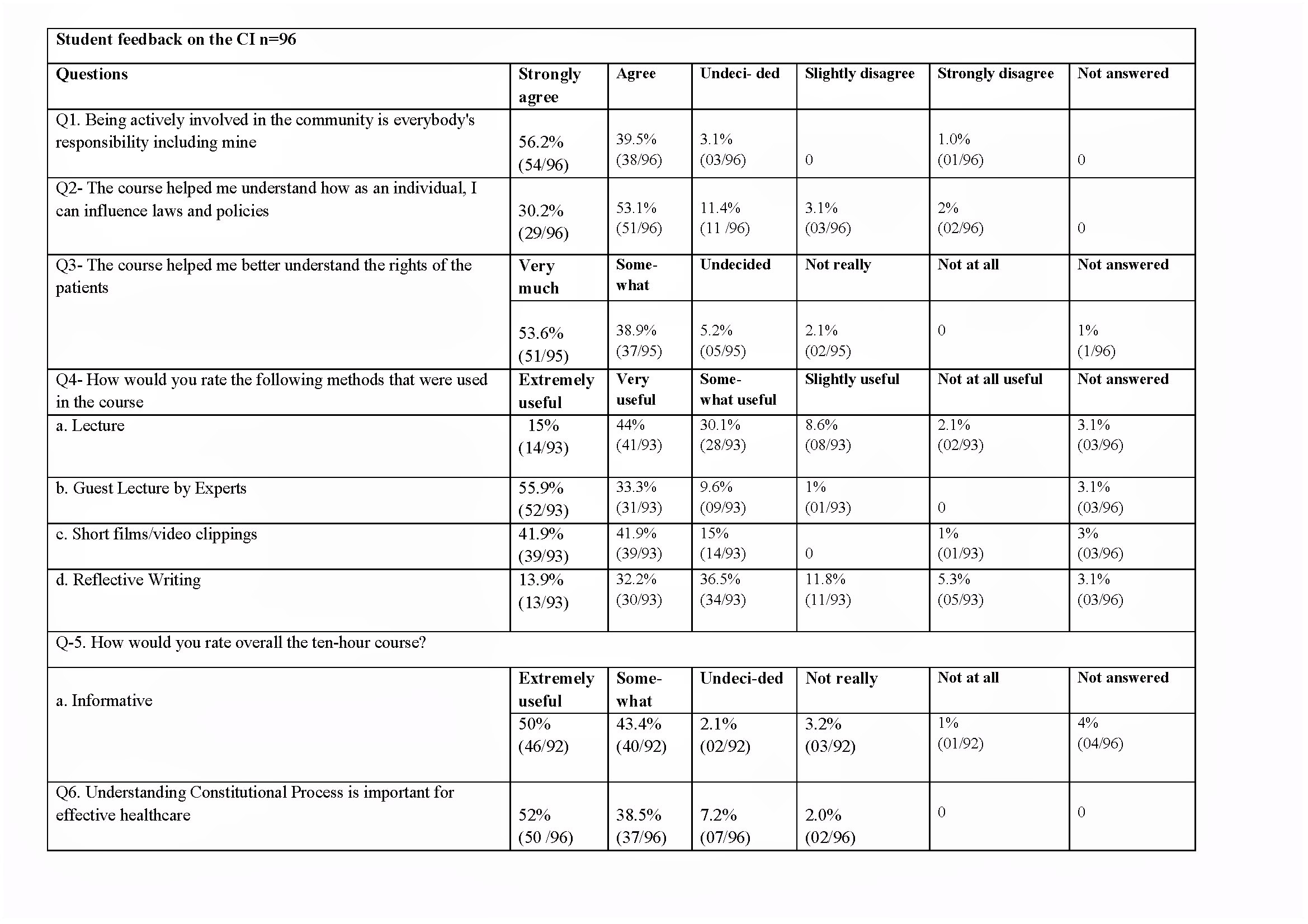

The results of the feedback are presented in Tables 4 and 5, and are summarised below as key result areas.

Need and relevance of the course

Over 95% of the respondents of the ES survey strongly agreed or agreed that the ES classes were useful for a medical student (Q1, Table 4). The reasons given by most of the class to support the relevance of the course was that it not only created awareness but also spurred their responsibility towards initiating change. This was considered important because of “The crisis in environment and a role that a doctor plays in integrating clean environment with good health.”

However, a quarter of the respondents agreed with the statement that there were far more important things than learning about the environment for medical students (Q.6, Table 4), thus contradicting – to a certain extent – the first positive response. There were no reasons given by students to explain why they felt that classes on the environment were not important. Those who wholeheartedly supported the course had this explanation: [the course] provides holistic training, not just being bombarded with technical and clinical knowledge of medicine

The CI course was also found to be useful in terms of information that was provided (Q.5, Table 5 with only 3.2% dissenting).

Students indicated that the course helped them identify and understand contemporary issues and problems. They felt this would help them as doctors working in the community. One of the respondents had this to say on the effectiveness of the course:

“Being vigilant of laws will help in questioning the authorities on wrongdoings.”

Feedback on the methods used like inviting guest speakers and the reflective nature of classes.

Students in both the ES and CI classes felt that guest lectures helped them in reflecting on and understanding “real world problems” better (Q.8, Table 4) with the following reasoning to support this view:

“All of us are living in a bubble, unaware of real problems of the world. So, getting people from outside is crucial.”

Some students said that they were aware of the issues but did not know how to respond to them and these classes in many ways were eye openers for them as the classes encouraged discussion and active interaction with the guest lecturers. As one person in CI class remarked:

“Active interaction with the speaker highlighted the diversity of opinions in class and enhanced my understanding of the topic.”

Another key pedagogical method to engage in reflection on life experiences, observation, and discussion; not to preach and provide solutions. Ninety-four percent agreed that the ES classes made them think about their role as both doctor and citizen. Similarly, for the CI classes the students’ preferred method of teaching (Q 4, Table 5, 55.9%), was the guest lectures by experts, followed by interaction, the use of short films/video clippings used as triggers for the lectures (41.9%), and finally the narrative writing.

Comments by students on the enriching nature of the classes:

On ES classes:

“Small steps can lead to big changes”

“Take steps to change things in my own community”

“Care for the common good”

On CI classes:

“I never thought that these issues [surrogacy] were important, or to be taken seriously! The class exposed us to a different viewpoint that was enriching.”

“Hearing the life struggles of transgender Ms. N and how she manages to overcome it, is truly inspiring.”

“[The] Interactions with Ms. N was engaging and thoughtful”

Possible deterrents in the effectiveness of these classes

A review of the attendance marked for the ES classes showed a reduction from 100% in the first two classes to 53% and 68% in classes 6 and 7, respectively, raising questions on what drives attendance at such classes in a medical school. In the CI classes, the attendance of students was 100% in the first class, reduced to 74% and 45% in classes 7 and 8, respectively.

In the feedback survey of the ES class, 16% admitted that they skipped classes because it was not linked to exams (Q.10, Table 4), with nine students being non-committal.

Reflection in the ES and CI course on becoming a Citizen Doctor

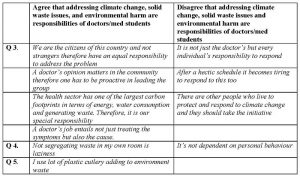

Perceptions of the individual student’s role and responsibility towards climate change, garbage problems, and environmental harmResponses to three questions (Q.3, 4, 5, Table 4) display the increased sense of individual responsibility felt by students towards being a responsive citizen. Three quarters of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that it was the responsibility of doctors to respond to climate change; about 64% felt responsible for the solid waste problems in their area, and 79% felt responsible for the environmental harm caused by their behaviour.

There were some who definitely felt that it was not a doctor’s responsibility to look at these issues. The reasoning given by students on both sides of the question is provided in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3: Responses on individual accountability to environmental issues

Perspectives on the social responsibility of the doctor and citizen participation in the legislative process

In response to the importance of a doctor’s role in the community as an active member (Q1 Table 5), 95.7% of students agreed that it is everybody’s responsibility including theirs, while only one out of the 96 disagreed. The students felt that they could take action that could potentially impact others and influence change. The following were some of the responses from students that reflect this:

“Being a doctor, I can bring about certain changes in laws and policies as we hold a privileged position. Being a citizen, I can fight for justice and set an example for others to change their mindset on issues that plague the country.”

“People’s participation especially in a democracy is important. Speaking against a known problem is the first step to change.”

In response to Q 3, Table 5 that addressed the patient’s rights, 92.5% of the students felt that, through the course they were able to understand and appreciate the rights of patients. Expressing their sensitivity to the socio-political realities of patients one of the students said,

“[the course] … helped me understand in what ways the patients might be denied rights and to be aware of the right and wrong.”

In response to the Q 2, Table 5, 83% of the students indicated that the course helped them to understand the significance of participating in and influencing the legislative processes, 5.1% said the course was not very helpful, and 11.4% were undecided.

On highlighting the perceived benefits of action by the medical fraternity, some students expressed their opinion thus:

“Healthcare is related in myriad aspects to the laws and policies of the country. For effective treatment to be provided to all, the medical fraternity and the legislature need to work together.”

“Doing small things, like just sending an email to the editor or creating campaigns in a small group, can be effective.”

There were students, who expressed a strong sense of frustration at the incompetence of the existing system saying:

“How can I change things in established institutions with people having rigid mindsets?”

“With rampant corruption how can you change anything in our political system today?”

One student identified the time constraints of the doctors as a deterrent to participation in the legislative process,

“It’s not possible for busy clinicians with a large number of patients to participate in the legislative process.”

The use of the first person reflects the sense of individual responsibility for one’s actions, as well as for being the initiator of change; the doctor was seen as a role model for the wider community.

Areas of improvement

Open-ended questions on topics that were not considered useful and suggestions on topics that could be included provided information for the improvement of this course. In the ES feedback, 86% did not find any topics unnecessary, while a few mentioned that topics should not be repeated, and a couple felt that actions such as tree planting and “carry your own cup” were not useful. For the CI course, 90% did not identify any topic that could be dropped. A small minority of students felt that historical snippets were unnecessary and that some topics were repeated.

A few topics were suggested for inclusion in the future. These included,

Suggestions were given for methods of teaching AND learning and these included more outdoor activities rather than lectures, case studies of other countries and how they have overcome problems, and more videos and news clippings. A few students also felt that the classes were rushed and there was not enough time for deeper reflection

Table 4: Responses to Citizen Doctor – ES classes

Table 5: Responses to Citizen Doctor – CI classes

Discussion

The Citizen Doctor course is a novel way of positioning ES and CI classes for first year students of the undergraduate MBBS course. Although the course was built around the core ideas and themes of environmental science and the Constitution of India, this was unique to St John’s Medical College. The objective of the course was to develop humane doctors by familiarising the young medical student with pressing contemporary issues and to encourage them to think as civic-minded professional doctors. These students responded positively to the course, as shown in the results of the feedback survey. They were able to

A minority of students felt that responding to problems of the environment and human rights were primarily the job of other people like social activists. Some reasons were:

A majority of students expressed the need to address these persistent issues as the underlying causes of several diseases and situations of ill health and to counter them through strong citizen initiatives.

Another positive feedback on the value of the Citizen Doctor course was regarding the reflective, challenging format of the sessions. In the words of the students, the nature of the course makes them “‘think” and pushes them to action or to recognize the need to change behaviour. Sustainable development and lifestyle choices were topics discussed that seemed to resonate with the students. This is in alignment with global deliberations on “Eco pedagogical frameworks” that serve as a theoretical foundation for education designed for environmental sustainability and global citizenship (18). These frameworks emphasise how diverse forms of knowledge influence public thinking and how the domination of knowledge, agency, and action needs to change from the hands of a few to the wider public. The impact of climate change and global warming, in terms of health or food access, shelter, and livelihoods, is going to affect the most impoverished and marginalised communities the most. Provocation to respond to issues of social injustice, inequity, irresponsible behaviours, and social consciousness is the requirement of every educational programme, especially at a university level, as these address future citizens and decision makers. It is even more compelling for young doctors, who can expand their circles of concern and influence. The UN’s “Vision of a Global Education” emphasizes that every person should acquire the capacity for enabling and ensuring that the least among the human race should flourish and transform for the better (19). This form of education is based on core values and not centred on knowledge alone. Scientists working on climate change reiterate the fact that public responses to climate change will not happen by imparting knowledge but by framing actions around people’s core values, identities, and ethical positions (20).

The Citizen Doctor course consciously began with key questions like “whose rights are we protecting?” Debates on the Surrogacy Bill and gender rights in healthcare by guest speakers led to long discussions with students that at times, conflicted with their ideas of “greater economic benefit” and were seen by students as “impactful”, “‘worthy”, and “thoughtful”. Some even acknowledged their “privileged role” in society as doctors and the significant role that they could play in bringing about change. This emphasises the social responsibility of the physician (21). Discussions on the holistic understanding of citizenship is valuable for medical students today, as there is a growing concern in India (22), as well as elsewhere (23) in the world, that an increasing number of students joining medical colleges are from affluent families; and are unaware of socio-economic vulnerabilities. This resonates with global efforts by international organisations like WHO that have issued guidelines for medical institutions on social accountability and responsiveness (24). Therefore, it is important to provide medical students an opportunity for dialogue and discussion (25) on these topics, creating a culture of participatory citizenship (26) that emphasizes the values of liberty, equality, and justice, keeping constitutional democracy vibrant.

In light of the new vision of the Medical Council of India for the creation of ethical, empathetic doctors, the findings of this study address these very values, and we believe that it would be important to include this Citizen Doctor course in the proposed AETCOM (Attitudes, Ethics, Communication) curriculum or in the Foundation Course. Ideally, an evaluation or certification for students completing this course should be mandated to give it its due credit and importance in the making of a good doctor. It also establishes an ethical position that academic excellence and marks scored in exams are not enough to make a medical student a doctor. Responsiveness to other issues, including the environment, which is the hallmark of empathy and virtue (27) are undeniably essential to be a good doctor.

While the findings of this study are encouraging, the ultimate proof of the outcome is in the sustained change of behaviour and mindset of these students, as they become doctors and citizen doctors.

Limitations

An important lacuna identified by students in the present curriculum was lack of engagement with the politics of development, structural issues, centres of power, and policymaking that influence change. The course focused on knowledge to an extent, but was unable to actively engage all students with real ongoing problems and advocacy processes to the desired extent.

Another limitation was that the Citizen Doctor Course was limited to the first year students; its development being structured around lecture time assigned by the university mandated ES and CI classes. We see potential in linking the National Social Service programme of medical colleges to this course and connecting the newly rolled out AETCOM curriculum to spirally integrating the intrinsic values of this course into AETCOM. We, however, did not attempt this.

The profile of the single institution that launched this course could also be a limitation in terms of the generalisability of the study to all medical colleges in the country. This medical college where the course was rolled out is in an urban area and places a high value on a social physician who is a link between medicine and society.

Conclusion

The Citizen Doctor course for first year MBBS students was found to be useful and beneficial. It evoked a sense of wider responsibility and of responsiveness, thus laying the foundation of a ‘Citizen Doctor’. ‘Eco-pedagogies’ are useful teaching approaches that follow a bottom-up method for social transformation. This pedagogical approach of the Citizen Doctor course, which is student-centered, where students are encouraged to think about issues beyond clinical medicine, would lead to critical thinking, focusing on issues beyond the “self” to the “other”. The evidence suggests that this course must continue and even expand to other years of the medical course, possibly even integrating with mainstream medical subjects. How do concerned citizens, whether medical students or health professionals, engage with policy and expand their circles of influence beyond their work and their own “clientele” of patients, who are citizens themselves? Small research studies, understanding health system responsiveness, and visits or weekend internships at civic organisations are some ways that this course could enrich the experience of the students.

However, because of practical issues like the burden of the syllabus, large numbers of students in a class, and non- availability of suitable teachers, it could be difficult to sustain the learner–centred approach of the Citizen Doctor course. But, by making it a required credit course under the new curriculum or by spreading it across the five years of the medical curriculum, it would be possible to have successful interventions at different stages. We also see the potential to link the National Social Service program of medical colleges to this course. Another possibility is to integrate the Citizen Doctor course in the AETCOM curriculum linked to an evaluation or certification for students completing this course, thus giving it its due credit and importance in the making of a good doctor.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the first-year medical students of the 2018 batch of St John’s Medical College Bangalore for their active participation in this course and their sincere feedback. We also thank Mr. Alisab for his help with data entry. The inputs of Dr Mario Vaz and Dr Olinda Timms and their review of the manuscript are acknowledged.

Competing interests: Both authors participated in the planning, designing, and teaching of the course.. Funding statement: None received.References

- Pandya SK. Something is rotten in our medical colleges. Indian J Med Ethics. 2019;4(2):92.

- Supe A. Medical humanities in the undergraduate medical curriculum. Indian J Med Ethics. 2012;9(4):263–365

- Majumder MAA. Should medical humanities be a part of the undergraduate medical curriculum? WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2012;2(1):68–9.

- Kalantri SP. Getting doctors to the villages: will compulsion work. Indian J Med Ethics. 2007;4(4):152–3.

- Goodin RE. Protecting the vulnerable: A re-analysis of our social responsibilities. 1st ed.: Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press; 1985.p-12.

- Vaz M, Kasturi A. Public health ethics in the medical college curriculum: Challenges and opportunities. In: Ethics in Public Health Practice in India. 1st ed; Singapore: Springer; 2018. p. 159–74.

- Parvin P. Democracy without participation: A new politics for a disengaged era. Res Publica. 2018;24(1):31–52.

- Habermas J. Citizenship and National Identity. In: Van Steenbergen, B. The condition of citizenship: an introduction in B.V. Steenbergen (Ed.), The condition of citizenship. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 1994. p.27.

- Hawthorne M, Alabaster T. Citizen 2000: development of a model of environmental citizenship. Global Environ Change. 1999 Apr 1 [cited 2020 Feb 15];9(1):25–43. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959378098000223

- Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(4):595

- Ambrose AJH, Andaya JM, Yamada S, Maskarinec GG. Social justice in medical education: strengths and challenges of a student-driven social justice curriculum. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2014 Aug;73(8):244-50.

- University Grants Commission. Foundation Course on Human Rights and Duties at Undergraduate Level University Press, New Delhi:UGC; 2001[cited August 2016]. P-14. Available from: https://www.ugc.ac.in/oldpdf/modelcurriculum/human.pdf

- Bharucha E. Textbook for Environmental Studies: For Undergraduate Courses of all branches of Higher Education. University Press, The University Grant Commission: India; 2005 [cited August 2016]. p- 8 .Available from: https://www.ugc.ac.in/oldpdf/modelcurriculum/env.pdf

- Rhoads RA. How civic engagement is reframing liberal education. Peer Review. 2003 Spring;5(3):25–8.

- Young IM. Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton University Press; 2011. Iris Marion Young (1999) Residential segregation and differentiated citizenship. Citizensh Stud. 1999 3:2, 237-252, DOI: 10.1080/13621029908420712.

- Young IM. Residential segregation and differentiated citizenship. Citizensh Stud. 1999;3(2):237–52. DOI: 10.1080/13621029908420712

- Ravindran GD, Kalam T, Lewin S, Pais P. Teaching medical ethics in a medical college in India. Natl Med J India 1997;10:288-9.

- Whiting K, Konstantakos L, Misiaszek G, Simpson E, Carmona L. Education for the sustainable global citizen: What can we learn from Stoic philosophy and Freirean environmental pedagogies? Education Sciences. 2018;8(4):204

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Global citizenship education: Preparing learners for the challenges of the 21st century. Paris: UNESCO; 2014[cited 2019 Jul 5]. Available from: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000227729

- Watts N, Adger WN, Agnolucci P, Blackstock J, Byass P, Cai W, et al. Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health. Lancet. 2015 Nov 7; 386(10006):1861–914. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60854-6

- Coulehan J, Williams PC, McCrary SV, Belling C. The best lack all conviction: biomedical ethics, professionalism, and social responsibility. Cambridge Q Healthc Ethics. 2003 Winter; 12(1): 21-38.

- Diwan V, Minj C, Chhari N, De Costa A. Indian medical students in public and private sector medical schools: are motivations and career aspirations different?–studies from Madhya Pradesh, India. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):127.

- Dhalla IA, Kwong JC, Streiner DL, Baddour RE, Waddell AE, Johnson IL. Characteristics of first-year students in Canadian medical schools. CMAJ. 2002;166: 1029 –35.

- Boelen C. Towards unity for health. Geneva: WHO; 2000.

- Dharamsi S, Ho A, Spadafora SM, Woollard R. The physician as health advocate: translating the quest for social responsibility into medical education and practice. Acad Med. 2011; 86(9):1108–13.

- Westheimer J, Kahne J. What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. Am Educ Res J. 2004; 41(2):237–69.

- Gribble MO. Environmental health virtue ethics. Am J Bioeth. 2017 Sep; 17(9):33–5. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2017.1353166.