ARTICLE

The ethical challenges of field research: A personal narrative

Jagriti Gangopadhyay

Published online on December 24, 2019DOI: 10.20529/IJME.2019.081

Abstract

One of the biggest components of the disciplines, Sociology and Social Anthropology is fieldwork. Despite the significance of fieldwork as a method, there is limited scholarship on the myriad experiences of the fieldworker. This commentary emphasises the need to document field narratives of researchers, while using the personal field experience of the author as a prototype. The author encountered these experiences in 2016 as part of an independent and self-funded study (Understanding aging in old age homes of Delhi, India) that she had conducted in Delhi post the submission of her PhD thesis titled: Three essays in aging: Social capital, family dynamics and transnational arrangements. The said thesis was completed at the Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, (pp: 1-169) from the year 2013-2018. In particular, the commentary sheds light on the ethical challenges faced during fieldwork. Specifically, this commentary, against the backdrop of the author’s encounters in an old age home, analyses the importance of primary themes such as the subjective-objective approach, passionate detachment, rapport building, critical reflexivity and the insider-outsider perspective while conducting fieldwork.Introduction

Fieldwork is an integral method for any form of study undertaken by sociologists and social anthropologists. Both are required to spend substantial amounts of their time in the field to understand any form of community. Fieldwork as a method gained popularity after Bronislaw Malinowski conducted intensive fieldwork among the Trobriand Islanders (1). In India, MN Srinivas, AM Shah and EA Ramaswamy, in their seminal book titled The fieldworker and the field (2), have elaborated at length on the significance of fieldwork for both Sociology and Social Anthropology. In particular, Srinivas et al suggest that fieldwork as a methodological tool has the ability to provide an intimate knowledge of the various social and cultural institutions and relationships present in all societies. Additionally, Shah and Ramaswamy (3), argue that fieldwork as a method will remain relevant, irrespective of the development and progression of societies. All students of Sociology and Social Anthropology have necessarily to do field research for post-graduate studies.Despite the emphasis on the field in both these disciplines,there is very limited scholarship on the experiences of the fieldworker. In particular, the discipline of Sociology has very little documentation of field narratives and focuses more on data. Against this backdrop, this paper highlights, in detail, the experiences of the author while conducting interviews in an old age home. In particular, this paper analyses the various factors that need to be considered before conducting interviews in an institutional set up. For instance, the paper discusses how interactions with the authorities, the personal background of the author and the nature of the research played a role in gaining access to the residents of the old age home. Finally, the paper sheds light on the two main ethical dilemmas of every sociological field researcher in India: the “insider-outsider perspective” (1) and the “subjective-objective” (2) approach. The former (insider-outsider perspective) highlights the extent to which the researcher has been able to absorb the culture of the society/community being studied. On the other hand, the latter (subjective-objective approach) indicates the balance the researcher needs to maintain so as to avoid personal biases and remain neutral towards the participants.

Who are you? Justifying the role of a researcher

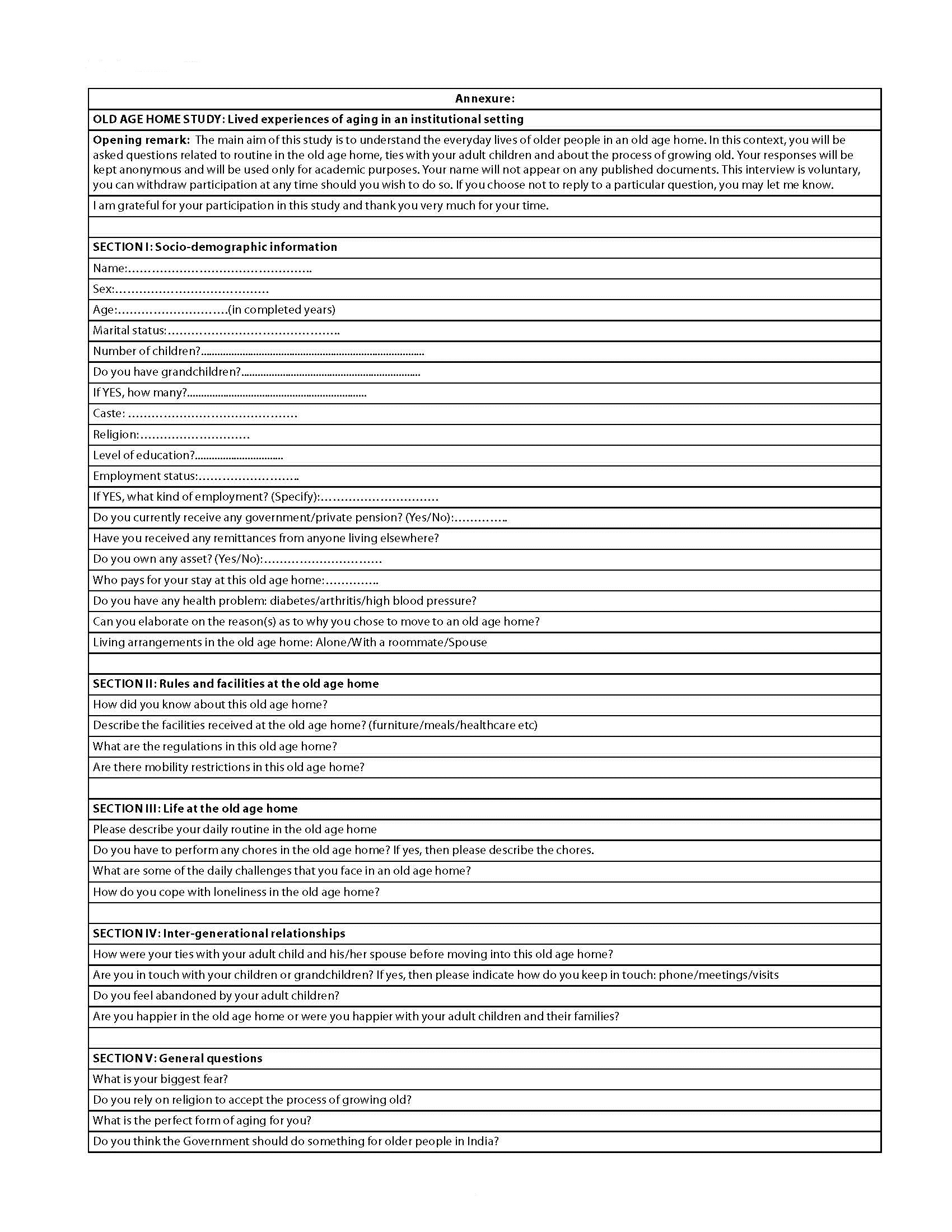

Collecting data in institutional settings has its own set of challenges. Several studies have noted that all types of institution whether they are educational organisations, hospitals, asylums or prisons, require permissions from multiple authorities to get access to the desired respondents (4, 5, 6, 7). Having read the literature on old age homes in India, I was aware of the various approvals I would need even to enter an old age home setting. I went with the required letters, justifying my work, my institutional affiliation and with copies of my consent form and questionnaire. The main aim of this study was to understand lived experiences of aging in an institutional setting. Though there are different types of elder care homes (government funded, paid homes and homes funded by a group of individuals or an organisation) available in India, this study was located in the “pay and stay homes”. In the “pay and stay homes”, the older adults mostly move in at their own will as opposed to the funded elder care homes, which mostly cater to abandoned and deserted older adults in India. Although my paper work was approved by the assistant of the caretaker, nonetheless, I was informed that the caretaker would interview me before I could do the interviews.My interview with the caretaker began with a series of personal questions: How old am I? Where am I from? What is my caste and religion? Am I married? Since I was married the next question was: How did my husband and in-laws give me permission to be here all alone? Why have I not changed my surname after marriage? Am I a vegetarian or non-vegetarian? I believe most of my answers did not satisfy the caretaker. Particularly, my response that I was married and had not been living with my husband, even though the reason was that I had been pursuing my higher studies in a different city. Additionally, though I was married the caretaker felt I was not “dressed” like a traditional married woman. I had not applied vermillion on my forehead for my interview and the caretaker did not appreciate that. After the personal queries, the caretaker finally started asking questions related to my work. He was worried that I might be a journalist disguised as a researcher and write a negative report about this particular old age home. In particular, his larger concern was that I would record my interviews. He interviewed me in detail about my work and also went through my questionnaire. He was also concerned that, as a young researcher, I might not fully understand the problems being encountered by my elderly respondents. Finally, I got his consent to carry out my study in the old age home. Despite, my elaborate session with the caretaker, I believe I got permission to do the interviews solely because I was a Hindu Brahmin. Post the interview, I was given a list of instructions to follow while doing data collection in the old age home. I was asked to dress “traditionally”, communicate in Hindi, to conduct the interviews between 9 am to 1 pm and not to offer any form of food to the elderly respondents.

Doing the interviews

My research examined the lived experiences of growing old in old age homes in urban India. Additionally, I was also asking the participants questions about filial obligations and their expectations from adult children, so as to understand the experience of the shift from the family to an institutional setting. The interview instrument was a semi-structured questionnaire with both open and close-ended questions. I intended to conduct in-depth narrative style interviews and the questions focused on adjustment issues, everyday routine and interactions, relationships with adult children, network ties and gender roles in different old age homes in urban India. A closer look at my research suggests that the respondents would need to share quite an amount of personal information with me. Specifically, the respondents would have to trust me to share their private lives with me. Though I was aware of the complex nature of my research, nonetheless, I planned to remain neutral and not get involved with my respondents.After I got permission to do the interviews, I was excited that I would finally be able to start my data collection. It was only after I began explaining my research to the elderly respondents that I realised that my own identity could not be removed from the equation. The old age home had both male and female residents and I got an opportunity to interview both. Like the caretaker, the respondents too, were intrigued about my background. They were surprised to know that I was married and yet living apart from my husband even though I explained that the reason was that both of us were pursuing our PhDs from different institutions. They were also very keen to know how I had met my husband and eventually got married, as my husband is a non-Brahmin, and also because his family had originally migrated from Bangladesh. They were particularly curious to know if we had faced any family resistance to our marriage. In fact, we spent a considerable amount of time discussing my marital life and my decision to pursue higher studies post-marriage. During the course of the interviews, they gave me multiple suggestions to complete my studies quickly and join my husband. Most of the female respondents also advised me to have children before I turned thirty. Despite feeling uncomfortable about their suggestions, I felt that since I had revealed intimate details of my private life, it helped me connect easily with my respondents.

The other significant learning I had while carrying out the interviews was when most of my respondents asked me what I was going to do with their data. They wanted to know if I was going to give it to the government or publish it somewhere. These questions made me realise that after I finished my study and left this particular home, I would probably not be in touch with any of my respondents. I was not sure if I would be permitted to meet them again, without any official agenda. I realised that while we as researchers continue looking for new forms of data in different fields, we always leave a part of ourselves behind in each particular field. Though we enter the field to collect data, it is crucial for us to understand that our respondents view us very differently. From the perspective of respondents, the researcher is a person trying to obtain intimate details of their everyday lives. Specifically, we need to comprehend that our respondents will be sharing their personal narratives with us in a very short span of time. Hence, it is important for researchers to view their respondents as human beings and not merely as sources of information.

The “insider-outsider” perspective

Scholarship on the insider-outsider perspective can be divided into two sets of studies. The first set have mostly commented on the unpredictable nature of the method of fieldwork (8, 9 ,10). In particular, these studies have indicated that the identity of the researcher as an “insider” or an “outsider” is ever changing in the field, and thus neither of these positions can be static. For instance, on the one hand the fieldworker has the advantage of being a stranger to whom participants may confide their intimate details. On the other, it is impossible to separate the intersections between the researcher’s identity and that of those being studied. Hence, as suggested by these studies, the process of doing fieldwork is complex and the researcher has to constantly navigate his/her position depending upon everyday interactions and relationships with the community being studied (8, 10). Acknowledging the uncertain nature of fieldwork as a method, another set of studies has emphasised the need to build a rapport with the participants (11, 12, 13). These studies have specifically indicated that the researcher needs to develop a certain rapport with the participants to receive authentic information. Though the researcher will be positioned with regard to his/her class, gender, and ethnicity, nonetheless, it is the task of the researcher to cultivate relations in such a manner as to gain the trust of the community (11,13) Summarising both sets of studies, it may be suggested that the researcher is required to maintain a balance between being an “outsider” as well as an “insider”.Given the limited number of days for which I was permitted entry to the old age home, rapport building for me was going to be difficult. As I began my interviews I was not sure to what extent the participants would share their personal details with me, given the nature of the study. I was specifically worried about my questions regarding inter-generational conflict. Once I began my interviews, I realised that being a stranger helped and that the respondents were eager to discuss with an outsider their conflicts with their children, their life in the old age home and how they dealt with the inevitability of death. One of the respondents gave me a tour of the entire old age home and showed me the library and the temple as well. In fact, some of the respondents also indicated their wish to possess a mobile phone which would enable them to call their grandchildren directly. Hence, despite my limited time to win the trust of my respondents, I believe I got access to their private lives because I acted more as a confidant My role as a confidant overtook my role as a researcher and my respondents started looking forward to my visits. In addition to being a patient listener, I also shared some of my own personal information and listened to their advice. I believe that this also helped in earning their confidence. For example, a couple of respondents gave me suggestions on how to maintain my health, to avoid becoming weak and dependent as they were. As I did not contest their advice and assured them that I would do as they advised, I believe that helped me establish a bond with my respondents.

Though the participants made me feel like an “insider” and shared a substantial amount of their personal life, nonetheless, as I wrote down my field experiences, I still felt like an “outsider”. Most of my respondents had shared details of their strained relations with their adult children and that they were unhappy in these old age homes. For instance, most of the respondents complained about the quality of food, the stress on religious rituals in the old age homes and the restrictions on mobility monitored by the home authorities. After the interviews, my respondents believed that sharing their woes with me might help them transform their situation. However, as a researcher, I knew that it was difficult to change their everyday lives. In particular, even if I had shared their concerns with the caretakers, I was not sure if concrete action would be taken. To maintain the ethics of the research, I guarded their interviews and always kept them anonymous right till the end. However, post completion of my fieldwork, I never went back to visit them. I still remember each one of my participants and our interactions; yet, once the work was done, I did not go back to enquire about their health or well-being. Perhaps the elaborate permission process and tedious paperwork prevented me from going back to my respondents, and as a result, I consider myself to be an “outsider” to my field – the old age home. Additionally, several of the participants had expressed their grievances with regard to the caretaker, the old age home in general, and the politics involving other inmates. During the course of my interviews I realised that they expected me to complain on their behalf and help improve their daily living conditions. However, I did not report any of their issues and left the old age home after my interviews were over. Hence, with regard to ethical dilemmas, I believe I – as an individual – failed my respondents. To my respondents, especially given their age and loneliness, my identity as a researcher did not mean much; it was me, the listening-person, the one with time and patience and the eagerness to hear them out that meant much more. It was on this latter front that I failed them, since my requirements as a researcher took the lead.

The emotional involvement of the field researcher has received very limited attention among academic scholars (2, 9) However, as ethnographers or qualitative researchers, we do tend to get attached to our field respondents. This makes it very difficult to practise “passionate detachment” (14, 15) in this context. The approach of “passionate detachment” requires scholars to consider fieldwork only as a method to obtain information from their research participants. In particular, this approach expects that scholars will refrain from demonstrating any form of emotion, such as anger, sadness, joy or worry, while doing fieldwork. As students of Sociology and Anthropology, we are trained to restrain our feelings from interfering with our fieldwork. Though we are taught to perceive our respondents only as sources of data, it is difficult to remove the human factor from the process of fieldwork. Despite numerous attempts to remain detached during interviews, I felt I was being unethical by not connecting emotionally with my respondents. Looking back at my own experience, I have to admit that I was moved by every narrative and empathised with each of my respondents. Thus, drawing from my own field encounters, I can state that the researcher does get enmeshed in the lives of the respondents, and the field itself becomes a part of the fieldworker’s identity.

To be subjective or objective in the field

Researcher’s bias is one of the biggest challenges faced by every anthropologist and sociologist in the field. As field researchers we are trained to adopt critical reflexivity and objectivity. Several qualitative studies have highlighted the need for the researcher to be self-reflexive and objective in order to avoid any form of bias from influencing the process of data collection (16,18). When I began my fieldwork, I had thought that I could be completely detached and objective. However, over the course of my fieldwork, I realised that it is impossible to isolate oneself from one’s field.

Srinivas et al (2) in their essays have indicated how subjectivities are bound to penetrate during fieldwork. One cannot leave behind one’s caste, gender, marital status or age while interacting with human respondents in the field. In particular, Srinivas et al (2) argue that fieldwork is a subjective experience, and therefore the anthropologist or the sociologist should write about their personal experience in detail. Corroborating their views on fieldwork, I gathered that my own background played a huge role in my interactions with my respondents. No matter how hard I tried as a researcher, it was impossible to remove one’s own self from the field. Against this backdrop, it may be suggested that while it is important to critically appraise the data, it is also imperative to take one’s own subjectivity into account.

Concluding thoughts

Reflecting on my experiences in the field began when I organised a symposium titled: “Women in the Field”, under the aegis of Centre for Women’s Studies and Manipal Centre for Humanities, Manipal. As one of the speakers at the symposium, when I talked about my fieldwork experience, I also evaluated it critically. Today, as I look back on my fieldwork during my PhD, I feel incomplete. I feel I could have achieved much more if I had allowed myself to get more involved with my respondents and had engaged more with the field and my respondents. Though I cannot change my past experiences, I hope to delve deeper during my future field endeavours.Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank Dr Nikhil Govind, Head, Manipal Center for Humanities), for his constant encouragement to write this piece, after I organised the symposium titled: “Women in the Field”.Statement on funding and competing interests:

This article did not receive any funding and there are no competing interests related to this article.References

- Malinowski B. Argonauts of the Western Pacific. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul Limited; 1922. 562 pp.

- Srinivas MN. The fieldworker and the field: A village in Karnataka. In: Srinivas MN, Shah AM, Ramaswamy EA, Editors. The fieldworker and the field. New Delhi: Oxford India; 1979. pp 19-28.

- Shah AM, Ramaswamy EA. Preface to the Second Edition. In: Srinivas MN, Shah AM, Ramaswamy EA, Editors. The fieldworker and the field. 2nd edition. New Delhi: Oxford India; 2004. pp 5-9.

- Minocha AA. Varied roles in the field. In: Srinivas MN, Shah AM, Ramaswamy EA, Editors. The fieldworker and the field. New Delhi: Oxford India; 1979. pp 201-15.

- Mercer J. The challenges of insider research in educational institutions: Wielding a double-edged sword and resolving delicate dilemmas. Oxford Review of Education. 2007; 33(1), 1-17.DOI: 10.1080/03054980601094651.

- Apa Z, Bai R, Mukherjee DV, Herzig CT, Koenigsmann C, Lowy FD, Larson EL. Challenges and strategies for research in prisons. Public Health Nurs. 2012 Sep; 29(5): 467-72.

- Block K, Warr D, Gibbs L, Riggs E. Addressing ethical and methodological challenges in research with refugee-background young people: Reflections from the field. J Refug Stud. 2013 Mar; 26(1): 69–87. DOI: 10.1093/jrs/fes002.

- Simmel G. The stranger. In: Simmel G, Wolff KH; Editors. The sociology of knowledge. New York: Free Press; 1921. pp 402-8.

- Naples N. A feminist rethinking of the insider/outsider debate: The ‘outsider phenomenon’ in rural Iowa. Qual Sociol. 1996; 19(1): 83-106. Doi: 10.1007/BF02393249.

- Sherif B. The ambiguity of boundaries in the fieldwork experience: Establishing rapport and negotiating insider/outsider status. Qual Inq. 2001; 7(4): 436–47.

- Kusow AM. Beyond indigenous authenticity: Reflections on the insider/outsider debate in immigration research. Symbolic Interaction. 2003;26(4): 591- 9.

- Sultana F. Reflexivity, positionality and participatory ethics: fieldwork dilemmas in international research. ACME. 2007; 6(3): 374–85.

- Calvey D. The art and politics of covert research, Sociology. 2008; 42(5): 905-18.

- Weber M. Politics as a vocation. In: Runciman WG, Editor. Matthews E, Transl. Weber: selections in translation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1978. pp 212-25.

- Haraway D. Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem Stud. 1988 Autumn; 14(3): 575-99.

- Jeanfreau SG, Jack L, Jr. Appraising qualitative research in health education: guidelines for public health educators. Health Promot Pract. 2010 Sep; 11(5): 612–17.

- Walker J L. Research column. The use of saturation in qualitative research. CanJ Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012 Spring; 22(2). 37-41.

- Potter S, Mills N, Cawthorn S, Wilson S, Blazeby J. Exploring inequalities in access to care and the provision of choice to women seeking breast reconstruction surgery: A qualitative study. Br J Cancer. 2013 Sep 3; 109(5): 1181-91.