RESEARCH ARTICLE

The Covid-19 effect on medical students’ perceptions of their profession: A mixed methods study from South India

Manjulika Vaz, Sumithra S, Reshma Ravindra, Suhas Chandran, Sandhya Ramachandra, Olinda Timms

Published online first on September 18, 2022. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2022.070Abstract

Covid-19 has devastated human lives and stretched the limits of the medical profession and health systems. Using the mixed methods of online survey and online focus group discussions, we assessed how medical students and interns of two medical colleges in South India viewed the profession they had chosen. Of the 900 participants, 571(63.4%) had a positive perception of the medical profession, 77(8.6%) a negative perception and 252(28%) were undecided. The year of study in medical school was significantly associated with their perception of the medical profession, with interns more likely to have a negative perception (p<0.001). An overwhelming 823(91.4%) participants remained confident of their career choice, but a higher proportion of interns were less confident or regretful about their choice of profession compared to first to fourth year students (p<0.001). Most participants experienced moral distress; they acknowledged a duty to care but were troubled by personal risk, inadequate protection, and limited resources. Gaps were identified in medical and ethics training particularly regarding uncertainties and coping with deficiencies of the health system as encountered in the pandemic. The essential role played by doctors with its required competence, care and ethics cannot be assumed or expected without investment in the making of the future doctor through more socially embedded medical education imparting the skills of understanding the public, responding to them and being the advocate for their equitable and optimal care. An ethics of responsiveness emerges as important for healthcare, also for medical education in preparation for future health crises.

Keywords: Covid-19, medical profession, moral distress, ethics education

Background

During the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, the medical profession faced extraordinary levels of stress and responsibility. Shortly after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, India closed its borders and went into a lockdown [1]. The health and economic impact of the pandemic was unprecedented and touched every section of society [2]. Health professionals, in particular, grappled with a rapidly unfolding health crisis with inadequate protection against an unknown virus and no specific treatment in sight [3]. Within weeks, hospitals across India were overwhelmed; stringent public health measures were enforced under the Disaster Management Act, 2005, to contain the spread of infection so that health infrastructure could be expanded along with quarantine facilities and testing [4].

Medical training was disrupted due to closure of educational institutions; students returned home and began online classes for the first time. Some volunteered at hospitals and care centres and witnessed a health catastrophe unparalleled in living memory. As the number of cases rose, there was an acute shortage of hospital beds; patients were advised to postpone non-emergency health needs and private hospitals were required to allocate beds for Covid-19 patients [5]. Health workers continued to work despite challenges like insufficient personal protective equipment (PPE) [6], uncertain treatment protocols and long work hours; many fell ill, succumbed to the infection [7] and even faced ostracisation by their communities [8]. While the Government and other agencies applauded the sacrifice and commitment of these “frontline warriors”, the health workers engaged in testing and contact tracing were stigmatised and even chased away by residents [9]. Health workers also had to grapple with new ethical challenges such as that of triage, resource allocation, end-of-life decisions, and handling death in great numbers [10, 11]. In addition, they faced the dilemma of weighing personal and family risk against their duty to care for Covid-19 patients [12].

While studies have been conducted on the psychological impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, [13, 14] and in the general population [15], not many have examined its impact on medical students, barring the responses to online learning [16].

Apart from reasons of human service and interest in medical science, students join the medical profession due to its social desirability, family pressure, academic scores and ranking in the entrance examination [17, 18]. Once selected, medical training has its challenges and is physically and emotionally taxing [19], with students having to cope with ethical dilemmas and moral distress [20]. The pandemic has exposed medical students — either directly or through media reports — to the realities of extreme work conditions, medical uncertainty, professional stress and social responsibility. Understanding these realities and acquiring proper coping strategies is regarded as a core clinical competency for medical graduates and trainees [21].

This study explored whether the pandemic had affected the medical students’ perceptions of the medical profession and their choice of career and the aspects affected by the pandemic.

Methods

This was a mixed methods study — a standardised survey explored perceptions in a larger sample while the qualitative method of Focus Groups was used to better understand the responses obtained in the survey.

Data collection — Quantitative

An online survey form was designed collaboratively by the authors based on a review of current literature, media reports, collective experience and narrated incidents on Covid-19 and medical professionals. In addition, it was validated by two medical professionals, experts in medical education and hospital ethics. Suggestions to sharpen the construction of the statements were incorporated and revalidated. The tool was pilot tested with a few non-participating students to check for face validity and the practical aspects of filling the form. It was then sent to students of the two participating medical colleges using the email IDs registered with the institution. The survey was open for the entire months of July and August 2020 with reminders sent out on WhatsApp to the students through their class representatives. The survey form had a letter of invitation (Study Information Sheet) and a consent form. Only those who consented could participate in the survey. The estimated time to fill the survey form was 20 minutes. Questions covering demographic details, perceptions of the medical profession during the Covid crisis, reflections on their choice of profession and their attitude towards ethical issues linked to Covid-19 and the medical profession were covered in the survey form. Of these, perceptions on attitude towards ethical issues linked to Covid-19 and the medical profession were collected using a 5-point Likert scale. The other sections had Yes/No categories and open-ended responses [study questionnaire available on request].

The sample and sampling method

Two medical colleges, privately owned and affiliated to the State Health University, in Karnataka, India, were studied. Medical training in India is spread over 4.5 years — the first year in pre-clinical, the second year in para-clinical and the remaining period in clinical training. After a mandatory year of internship, the Medical Council registration is awarded to the student for medical practice. College 1 admits 150 students with 60 interns as per the earlier mandated intake, whereas College 2 admits 150 students (including interns) every year. Both medical college hospitals were designated Covid centres and had testing facilities as well as Covid confirmed in-patients. In both the colleges, students from the first to fourth year had online/virtual classes during the period of the study (in 2020) when the country was under lockdown.

As there were no previous studies looking at a similar impact on perceptions of the medical profession, sample size was estimated based on the assumption that approximately 20% of students would have a change in perception regarding the medical profession as a result of the pandemic. To maintain a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a 10% relative precision, a sample size of 1024 was estimated across the two medical colleges, distributed approximately equally across each year of study.Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) for the continuous variables; number and percentages for the categorical variables. Chi-square was used to test the association between the year of education and the perception of the medical profession along with characteristics of the study participants. Considering the distribution of the numbers, responses on the Likert scale were clubbed for analysis — “Strongly Agree” and “Agree” as Category 1, “Strongly Disagree” and “Disagree” as Category 2, and “Can’t Say” as Category 3. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the factors associated with positive and negative perceptions of the participants about the medical profession compared to those unsure about their perception. Variables that were significant in the univariate regression along with gender and years of education were subjected to multivariate regression analysis. Odds ratios (OR) were adjusted for gender and the year of study. P value less than 5% was considered statistically significant. All the analyses were carried out using SPSS version 26.0. Content analysis was done manually for the responses to the open-ended questions and are reported with the year of study and gender of the respondent.

Data collection — Qualitative

Following the survey, online Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were held using the Microsoft Teams platform. A total of six FGDs were conducted, three per college, across the different years of study, including the interns in both colleges. Students were asked in the survey about their willingness to participate in the FGD. There was no significant difference by gender and by perceptions of the medical profession (positive and negative) between those who were willing and those who refused to participate in the FGD. From those willing, 8-10 students per batch were randomly selected through the SPSS software to get a mix of those who indicated a positive and negative perception of the medical profession. Though socio-demographic factors were not selection criterion, every focus group was homogenous in terms of their age with a balance of gender. A specific consent was taken for participating in the FGD, particularly for its audio recording with assurance of confidentiality given, and a request that participants too kept confidential what they heard from their peers [Supplementary File 1, available online only].

Thematic analysis

The FGD audio data was transcribed by an external agency and manually coded by multiple investigators using a combination of inductive themes and those generated from the survey form. A coding framework was developed and subsequently used to recode the data using the NVIVO version 12 software. The themes and sub themes were explored by the year of study and have been presented using the FGD numeric code followed by the year of study.

Ethics statement

The study was reviewed and granted ethics approval by the Institutional Ethics Committees (IEC) of both colleges (IEC Study Ref No 152/2020 and SDUMC/KLR/IEC/142/2020-21) permitting the voluntary, online self-administered survey and the online FGD. No incentives were offered to students to participate.

Results

Of the 1400 students contacted in both colleges, 987 responded and 900 consented to participate (65% response rate, with 61.3% female respondents). Of the 900 responses, 384(42.7%) were from College 1 and 516(57.3%) from College 2.

Characteristics of participants

Of the 900 participants, 232(25.8%), 178(19.8%), 216(24%), 209(23.2%) and 65(7.2%) belonged to the first, second, third, final years and internship, respectively [Table 1]. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 26 years. About 594(66%) were from South India and 236(26%) of the participants reported having doctors in the immediate family (including parents, siblings, and grandparents). The distribution of gender and presence of doctors in the family were similar across all years of study.

Table 1: Characteristics of the survey respondents and perception of the medical profession during the pandemic

Variable |

Category |

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Year 4 |

Internship |

TOTAL 900 |

Difference across years |

| Enrolment site | College 1 | 115 (49.6) | 91 (51.1) | 101 (46.8) | 71 (34.0) | 6 (9.2) | 384 (42.7) | <0.0001 |

| College 2 | 117 (50.4) | 87 (48.9) | 115 (53.2) | 138 (66.0) | 59 (90.8 | 516 (57.3) | ||

| Gender | Male | 86 (37.1) | 71 (39.9) | 88 (40.7) | 83 (39.7) | 19 (29.7) | 347 (38.6) | 0.554 |

| Female | 146 (62.9) | 107 (60.1) | 128 (59.3) | 126 (60.3) | 45 (70.3) | 552 (61.4) | ||

| Doctor in the family | Yes | 53 (22.8) | 46 (25.8) | 59 (27.3) | 54 (25.8) | 24 (36.9) | 236 (26.2) | 0.251 |

| No | 179 (77.2) | 132 (74.2) | 157 (72.7) | 155 (74.2) | 41 (63.1) | 664 (73.8) | ||

| Perception of medical students of the medical profession during the pandemic | ||||||||

| Status of perception * | Positive | 156 (67.2) | 120 (67.4) | 138 (63.9) | 136 (65.1) | 21 (32.3) | 571 (63.4) | <0.0001 |

| Negative | 13 (5.6) | 18 (10.1) | 18 (8.3) | 12 (5.7) | 16 (24.6) | 77 (8.6) | ||

| Confidence towards their career choice | More confident | 218 (94.0) | 167 (93.8) | 194 (89.8) | 194 (92.8) | 50 (76.9) | 823 (91.4) | <0.0001 |

| Less confident | 14 (6.0) | 11 (6.2) | 22 (10.2) | 15 (7.2) | 15 (23.1) | 77 (8.6) | ||

| *Note: The ‘Non responded’ category was excluded while testing the association between status of perception and year of education. | ||||||||

A total of 50 students participated in six FGDs, of which 27 were female. There were nine students from Year 1, ten each from Year 2 and Year 3, nine from Year 4 and 12 interns. The FGD participants logged in from multiple locations across the country. It can be noted that the analysis of the survey response of those who agreed to participate and those who did not agree to participate in the FGD, showed that there was no significant difference by gender and in their perceptions of the medical profession (positive and negative). However, the year of study was significant, with the proportion of refusals to participate being higher in the interns’ batch, with no significant difference between first four years.

Perceptions of medical students about the medical profession during the pandemicOf the total participants, 587(65.2%) stated that their perceptions towards the medical profession had changed during the pandemic, 209(23.2%) indicated that there was no change and 104(11.6%) were undecided.

Of the 900 participants, a majority (571, 63.4%) had a positive perception of the medical profession, 77(8.6%) reported a negative perception and 252(28%) were undecided [Table 1].

The reasons given by those with a positive perception were primarily the importance and respect accorded to the doctor who served an important need in the health crisis; the heroic image of the doctor, as illustrated by these quotes:

“The situation has made me more aware of the importance of us doctors and the role we have to play in such critical conditions.” (Year 4, F)

“Even though the negativity towards doctors, which was also there before, is continuing, I feel many more people are looking towards the medical profession with lot more respect and gratitude.” (Year 2, F)

“While others are losing jobs, doctors are getting to help people, it just not only is a sign of job security as a profession, [but] it also makes it gratifying and gives a noble status.” (Year 2, M)

The reasons given for negative perceptions fell into three categories — the public attitude towards the healthcare profession; the failing and non-responsive health system within which doctors were targeted; and the disruption of medical training. Representative quotes are given below:

“Doctors are going through a tough time because of the people’s carelessness.” (Year 1, M)

“After the pandemic a lot of doctors have disappeared, junior doctors are being forced to attend duty …hospitals are cutting pay of health professionals.” (Intern, F)

“No learning, no exams… clinical knowledge through wide range of cases is missed.” (Year 3, M)

There was no significant association between enrolment site (College 1 or 2), gender, or having doctors in the family, and perception categories. However, the year of study was significantly associated with the impact on their perception. The interns were more likely to have a negative perception of the medical profession (Unadjusted OR = 2.76, 95%CI = 1.17 – 6.52). About 567(63%) of students reported a personal fear of contracting Covid-19 and knew doctors or colleagues infected with Covid-19. This, however, was not significantly associated with the students’ perception of the profession. It was noted that 87(9.7%) of the participants had direct exposure to Covid cases. This was significantly associated with the change of perception (p<0.001). A higher proportion of participants with positive perception (42, 48%) reported to have direct exposure to Covid cases, compared to only 18 (20.7%) with negative perception (Unadjusted OR = 2.54, 95%CI = 1.31 – 4.92). When adjusted for year of education and gender, this was, however, not statistically significant [Supplementary File 2, available online only]

Thematic analysis of the qualitative data reveals feelings of anger and anxiety, especially when a family member tested positive and had to isolate at home or return to work at the hospital once the test turned negative. Interns expressed distress while on Covid-19 duty, linked to suspect but unconfirmed Covid-19 patients who feared stigma associated with a Covid positive test result.

“… while working in the [Covid] suspect ward I feel so much distress because patient and patient attender are so anxious. … they are asking repeatedly … this is happening, what is the effect…? when will the report come? I don’t have any symptoms. I’m fine…only breathlessness… When we shift a patient to the ICU, then they’re so afraid… can that …happen to me? Will that person come out alive?” (FGD 02_05, Intern)

“I also faced similar situations… this Covid is still a stigma in our society, even if we tell the patients or patient’s attender not to think that Covid positive is that bad, they do not agree with us. We face difficulties in communication with the patient attenders.” (FGD 02_05, Intern)

Positive and negative factors contributing to students’ perceptions

Fulfilling an essential duty (547, 60.8%) and going beyond the call of duty (312, 34.7%) were considered most inspiring among doctors’ responses to the Covid pandemic, with “support for family/friends” and “recognition from society” coming lower down the order [Table 2]. A higher proportion of interns (51, 78%) considered fulfilling an essential duty to be inspiring (p<0.001), while “going beyond a call of duty” was less inspiring (8, 12.3%).

Table 2: Positive and negative factors contributing to students’ perceptions

Factors |

Total |

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Year 4 |

Interns |

Difference across years |

| Inspiring factors in the role of the medical profession in the pandemic | |||||||

| Fulfilling an essential duty | 547 (60.8) | 129 (55.6) | 108 (60.7) | 122 (56.5) | 137 (65.6) | 51 (78.5) | 0.005 |

| Support for family and friends | 15 (1.7) | 2 (0.9) | 3 (1.7) | 4 (1.9) | 4 (1.9) | 2 (3.1) | 0.767 |

| Recognition from Society | 11 (1.2) | 7 (3.0) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.4) | 0 | 0.036 |

| Going beyond the call of duty | 312(34.7) | 92(39.7) | 64(36.0) | 86(39.8) | 62(29.7) | 8 (12.3) | <0.001 |

| Nothing inspiring | 15 (1.7) | 2 (0.9) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.4) | 3 (1.4) | 4 (6.2) | 0.059 |

| Disturbing factors in the role of the medical profession in the pandemic | |||||||

| Increased risk/ harm to self and family | 347(38.6) | 107(46.1) | 62(34.8) | 77(35.6) | 77(36.8) | 24(36.9) | 0.101 |

| Reduced societal support | 338 (37.6) | 73 (31.5) | 83(46.6) | 82(38.0) | 86(41.1) | 14 (21.5) | 0.001 |

| Inadequate working conditions | 147 (16.3) | 33 (14.2) | 22(12.4) | 32(14.8) | 34(16.3) | 26 (40.0) | <0.0001 |

| Moral dilemmas | 30 (3.3) | 8 (3.4) | 4 (2.2) | 12 (5.6) | 5 (2.4) | 1 (1.5) | 0.268 |

| Others | 16 (1.8) | 4 (1.7) | 4 (2.2) | 5 (2.3) | 3 (1.4) | 0 | 0.754 |

| No troubling factor | 21 (2.3) | 7 (3.0) | 3 (1.7) | 7 (3.2) | 4 (1.9) | 0 | 0.509 |

In the group discussions — recalling incidents of doctors responding to the call of duty, serving others, saving lives and working selflessly in spite of the pandemic — appeared to inspire and motivate young medical students to model themselves on those doctors.

“… when we’re at home, we don’t know… we haven’t seen the other side. We get this [media] news saying that the doctors aren’t ready to see patients. But when I saw the doctors at the hospital and the nurses working so hard … working to give everything they can to save a patient or help them recover… honestly after seeing that, I felt that someday if I have to give my everything to save… someday, I will do that.” (FGD 01_01, Year 1)

“…This is one job where I can get into the shoes of others and alleviate their pain. A chance to be more compassionate …” ( Year 3, F)

Increased risk to self and family (347, 38.6%), reduced societal support (338, 37.6%) and inadequate working conditions (147, 16.3%) were factors that disturbed the participants about the functioning of doctors in the pandemic. A high proportion of interns (26, 40.0%) stated that inadequate working conditions was the most disturbing factor while reduced societal support was considered the most disturbing factor by participants from other years of study [Table 2]. None of these factors was significantly associated with the perception categories.

Only 15(1.7%) and 21(2.3 %) participants said there were “No inspiring” and “No troubling” factors, respectively [Table 2].

This was reiterated in the qualitative data. Those inspired by the role of doctors in the pandemic were also distressed and demoralised by negative incidents occurring around them. Most of these incidents were reports in the media, messages circulating on social media and from peers. Four sub themes emerged:

a) Public abuse, disrespect, stigma against doctors.

b) Unfair treatment of doctors related to low salaries, refusal of leave applications, and high risk due to inadequate PPE.

c) Unethical practices of doctors and hospitals.

d) Doctors becoming scapegoats for faults of the health system.

Influence of current perceptions of the medical profession on choice of medicine as a career and future specialisation

Only 77(8.6%) participants were less confident of or regretted their choice of career. Association between the confidence level (more/less) of their career choice and the year of study showed that a significantly higher proportion of interns (15, 23.1%) reported to be less confident of their career choice compared to all other groups (6.0%, 6.2%, 10.2%, 7.2% for year 1 to 4, respectively) (p<0.001) with no significant difference between year 1 to 4 [Table 1].

On the contrary, group discussions revealed that reasons for joining medicine were reinforced by the pandemic across all years of study including the interns. They highlighted the need for doctors and the importance given to their role, and that this was unlikely to be the last pandemic. They felt that risks from infectious diseases and negative views from society did not change their own conviction that this was the right profession for them.

“I believe, the way we think is the way we perceive things. So, we are aware of the risk, we are ready to take the risk and if we are ready, we go ahead with it. There is risk in every single profession. Now the situation has made it a little riskier in the health profession. So, when we are in this profession, and if we love it so much, none of these issues outside must affect that.” [FGD 01_03, Year 3]

However, participants with a negative perception of the medical profession were less confident of their choice of career (Unadjusted OR = 0.19, 95% CI = 0.10 – 0.38, Supplementary File 2), even when adjusted for gender and year of study (Adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.206, 95% CI = 0.10 – 0.41).

Five hundred and fifty (61%) participants said family members or friends influenced their views about the course/choice of profession after the onset of the pandemic, with no significant difference across years of education, including internship. Both positive and negative perceptions were significantly associated with the influence of family members or friends. This remained true when adjusted for gender and years of education (Positive perception AOR = 4.65, 95% CI = 3.37 – 6.43, and negative perception AOR = 2.05, 95% CI = 1.18 – 3.53).

The qualitative data suggests that this family influence may act as an expression of concern and worry on the one hand, or of pride and encouragement on the other. While some parents reinforced ideas of service and medicine being a “noble profession”, other parents, especially those of students in the senior years, were concerned about completion of the course and gaps in clinical training since students were sent home.

“…after this pandemic, they have told me, at least once a month, that you chose the wrong profession. It was my passion to join MBBS … they’re worried about my course completion.” (FGD 02_04, Year 4)

“At the start, they were very proud that I [had] got into medicine and my mom, all she wanted me to [do was] treat people. Because in my family none of them are in medicine …. after this pandemic, they [family] were saying, why did you send your daughter there? … she [Mother] is a little worried now because we are sitting at home, and this is the final year … we need to have clinical practice and be strong in that. She wants me to go back to college and study more… but she tells my relatives that I came back home during this pandemic, thank God …” (FGD 02-04, Year 4)

Only 56(6.2%) participants felt the pandemic had changed their minds about a future area of specialisation, while an overwhelming 844(93.8%) of participants expressed no change or were undecided about their future area of specialisation.

The choice of specialisation was not linked to subjects of interest or need arising out of the pandemic. Rather, participants indicated that their choice of specialisation would be an outcome of scores earned in the postgraduate qualifying exam NEET (National Eligibility cum Entrance Test).

Moral / ethical distress faced by doctors influencing perceptions of the profession.

As seen in Table 3, around 808(90%) of participants agreed that these were distressing times and that doctors had a duty to care for Covid-19 patients irrespective of the risks. Multivariable analysis adjusted for gender and year of study showed that even those with positive perceptions of the medical profession considered these to be distressing times (AOR = 2.16, 95% CI = 1.35 – 3.44). Participants with a negative perception of the medical profession were less likely to agree that doctors had a duty to care for Covid-19 patients irrespective of the risks involved (Unadjusted OR = 0.49, 95%CI = 0.25 – 0.95); however, in the adjusted analyses, significance disappeared, and these participants were also more likely to agree that it was acceptable if the doctor chose personal safety over care of the patient (Unadjusted OR = 2.41, 95% CI = 1.34 – 4.33). Above 90% (844) of the participants agreed that inadequacy of resources in the pandemic was a crippling challenge for medical professionals and affected the treatment of patients. A significantly higher proportion of interns and final year students felt that medical professionals were unfairly forced to make difficult decisions for Covid-19 patients (p = 0.003), a view held by those with both positive and negative perceptions of the medical profession. Although statistically not significant, a higher proportion of interns (24, 37%) disagreed with the statement that medical professionals are trained to handle the ethical dilemmas during the present crisis (p = 0.07).

Table 3: Perceptions of moral / ethical distress faced by doctors by year of study.

Statements |

Category |

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Year 4 |

Interns |

Difference across years |

| These are distressing times | 808 (89.8) | 203 (87.5) | 165 (92.7) | 197 (91.2) | 183 (87.6) | 60 (92.3) | 0.423 |

| Doctors have a duty to care for COVID 19 patients irrespective of the risks | 803 (89.2) | 211 (90.9) | 15 (87.1) | 198 (91.7) | 186 (89.0) | 53 (81.5) | 0.396 |

| It is acceptable if the doctor chooses personal safety over care of the patient. | 541 (60.1) | 124 (53.4) | 117 (65.7) | 128 (59.3) | 128 (61.2) | 44 (67.7) | 0.087 |

| Limited resources in such a pandemic is an unfair challenge for a medical professional as they cannot provide healthcare as required to all patients | 844 (93.8) | 212 (91.4) | 168 (94.4) | 199 (92.1) | 203 (97.1) | 62 (95.4) | 0.072 |

| Medical professionals are left alone to make difficult decisions for COVID 19 patients | 652 (72.4) | 157 (67.7) | 117 (65.7) | 159 (73.6) | 166 (79.4) | 53 (81.5) | 0.003 |

| Medical professionals are trained to handle ethical dilemmas in times of crises | 667 (74) | 199 (86) | 120 (68) | 157 (73) | 150 (72) | 41 (63) | 0.007 |

Participants with a positive perception of the medical profession were more likely to agree that medical professionals were trained to handle ethical dilemmas during crises (p < 0.001, Unadjusted OR = 1.82, 95%CI = 1.31 – 2.54). Acceptance of the choice of personal safety over care of the patient was significantly associated with a negative perception, adjusted for gender and year of education (AOR = 2.16, 95%CI = 1.19 – 3.92).

The qualitative data provided a more nuanced understanding of the “pull and push” of circumstances at the individual level and at the level of the healthcare system, governments, and public at large. While service and duty to treat patients was seen as central to the doctor’s role, more so at the time of a pandemic, the imperative of ensuring the safety of doctors in order to fulfil that duty was unequivocal. The mood and the reasoning come together under the theme “Justice for doctors”, balancing care of self with duty to care for others.

“… once I’m safe only then can I be of service to society. That’s my concept. If I am infected, that means I’m not bothering about being contagious to society. So, if I’m not safe, then there is no meaning in giving service to society. Being safe and making others safe, must be the aim.” (FGD 01_03, Year 3)

“If I’m not getting my required protective equipment, I should be able to refuse this job and to stand up to the management … regardless … I believe all the doctors who face this should unite.” (FGD 02_04, Year 4)

“It shouldn’t come to the point where one has to choose between one’s own health and the responsibility of carrying out one’s job.” (FGD 01_06, Interns)

It also revealed the dilemmas and frustrations with what was seen as the irresponsible, “hypocritical” behaviour of the public and governments.

“[Banging plates, ringing plates…] that was very hypocritical I feel, because people celebrated the medical profession, but then at the same time, are not willing to do their role that is [to follow] their basic precautions [masking and staying home]. And at the same time, … doctors were assaulted. Well, that’s hypocritical. So, don’t ask people to celebrate doctors, just do the basic thing that every person can do, which will help doctors …” (FGD 01_06, Interns)

Challenges of ethics training also emerged, not just for doctors but in other spheres of life and the public at large, as highlighted in this quote:

“I believe that the problem is, with how doctors are taught. And when I say doctors, it is not to put the blame on them. But it is to do with the entire education system in our country. …in all the other fields and [in] all the other areas of a person’s schooling, no one really focuses on how you should behave and how you should respect other people.” (FGD 01_03, Year 3)

Opportunities for learning and ways of coping during the pandemic

About 686(76%) of participants considered the pandemic to be a good learning experience; more interns than other students disagreed (24, 37%).

Three themes emerged that explained why the pandemic was not necessarily a good learning experience. “Too high a price to pay for learning” was expressed by the interns, while “limited clinical exposure” was cited by both interns as well as students from year 3 and year 4, and the common theme across years was “Limited learning”.

“From both our personal and our whole community point of view, there’s been too much life loss, too much hospital health costs and economic problems everywhere. …. many interns had also become [COVID] positive, and they suffered the disease as well. So, I don’t think it’ll be fair to say it’s been a learning experience.” (FGD01_06, Interns)

“We’ve not learned many procedures as we are mostly into COVID duties. … any case, with any symptoms, the diagnosis is directed towards COVID…we’re not thinking about anything else. The number of patients coming to our hospital is low because they are scared of Covid, so exposure is less, and we are also learning less. … we need to do more procedures. As an intern, I’m actually affected.” (FGD 02_05, Interns)

“…we were taking it as holidays and were thinking that after 15 or 20 days it [college] will be begin… after one or two months when we saw the syllabus and online classes we had adjustment issues, network [connectivity] issues … I believe that the whole MBBS course cannot be taught online like this. So, it is a bit demoralising. But at the same, there is no solution to this problem right now… something is better than nothing. And it’s totally unpredictable in the future also.” (FGD 02_02, Year 2)

Two-thirds (616, 68.4%) of the participants across the years of study considered it difficult to cope with uncertainties during the current pandemic. Mood swings, fears, lowered self-esteem were some responses that emerged from qualitative discussions.

“During these six months, we were totally with mood swings … and sometimes we were bored. We want to go back … it is not the same … it’s totally unpredictable in the future also…” (FGD 02_02, Year 2)

“… when I get scared of the exams, then I start studying for some days, then I just don’t know …, first I used to enjoy this lockdown in March, then in July [I thought] there’s going to be exams, then again, I just stopped studying, I didn’t even touch my books. And then again, I get scared, it’s not constant.” (FGD 02_04, Year 4)

The medical course and its association with exams, the need to get back to clinical training and fears of their future were explained as sources of stress and anxiety.

The frustrations expressed due to the uncertainties were also due to having no end in sight to the pandemic, the inability to answer questions on Covid-19 from friends and patients with certainty, and the inability to make plans for themselves.

Two-thirds (574, 64.0%) of the participants had discussed their difficulties with somebody [260 (45%) with multiple people, 153 (26%) with parents, 154 (26%) with peers]. Overall, 392/690 (56.8 %) of participants found these discussions helpful; this was significantly higher among interns (p = 0.02). Discussions of difficulties with family and friends had no association with their change of perception of the medical profession.

Qualitative data showed that students found discussions with families and friends both cathartic and frustrating.

“People who didn’t respect my profession that much and thought it’s time waste to read so much now actually understand my role. They also understood that I will be a great help to them during other situations like this.” (Intern, M, 24 Years)

They expressed the view that this pandemic had inadvertently reiterated the humanitarian aspect of the medical profession.

“We didn’t expect a pandemic to be coming into our lives. But we when we signed up for this course, we already stated that we would help to save humanity from it.” (FGD 02_02, Year2)

Volunteering was suggested as a coping mechanism and an opportunity for learning. Stepping out of routine student activity and doing things for others appeared to be emotionally satisfying.

“… we can do such amazing things to help people even at such stressful times, no matter what the doctors are currently going through … we can help raise funds … because Covid treatment requires a lot of funds and there is no way that you cannot treat a patient, and that amount is required … you expect the people [with funds] to contribute towards the betterment of the nation [so that] we could have reduced charges for the poor so that we can all actually support the crisis.” (FGD 01_01, Year1).

Lessons for the medical curriculum and medical training

Qualitative data indicated areas where medical students both at the hospital and community levels could broaden medical training to address wider pandemic response interventions. Two themes emerged:

People skills and ethical behaviour

In response to reactions of the public to doctors, students felt that communication skills and ethical handling of difficult situations should be formally taught and emphasised in all medical colleges.

“What has shown up during this pandemic is that a doctor needs to be equipped with people’s skills which is the ability to communicate with other people easily and thus prevent a lot of the… violence against doctors.” (FGD 01_03, Year 3)

Handling uncertainty

A pandemic situation response was not encountered earlier in their medical curriculum even though the epidemiology and spread of infectious diseases were covered. The ability to work with and through the unknown seems to be a gap in training.

“We’ve all seen infections; we have studied them. But this phenomenon of infectivity, with so many patients, with so much uncertainty each day, the guidelines changing each day, those who are susceptible was changing, diagnostic criteria was changing. And suddenly, so many of your colleagues at home, everyone was getting positive, you are unsure …. for lot of people, they were unprepared for the sort of situation…” (FGD01_06, Interns)

Discussion

This mixed methods study was conducted across two medical colleges in South India. It revealed that despite the Covid-19 pandemic and its pressures on doctors and the medical system, students’ perceptions of the medical profession remained largely positive (63.4%) and more than 90% of the students expressed no regret about their choice of profession. This could possibly be an overzealous response by the medical students to validate their choice of career, as considerable effort is applied to gain a seat in a medical college in India, fed by social desirability and family pressures to enter the medical profession. The college of study, gender of the student or presence of a doctor in the family did not significantly impact their perception. Rather, it was the year of study that was significantly associated with altered perception. Qualitative data from the open-ended questions and from the Focus Group Discussions revealed the multiple pulls and pushes that influenced the perceptions of medical students towards the profession of their choice.

The pandemic and its focus on the medical profession was a reality check for the medical students. It either reinforced their reasons for joining medicine such as service and humanitarian response or it brought to the fore the risks and “sacrifices” that are expected from the medical profession. It also revealed that medical students look up to doctors in the profession as role models. “Fulfilling an essential duty” was considered by students across all years of study, including interns, as most inspiring about a doctor’s role in the current pandemic; they described heroic acts of saving people’s lives, being a first responder, being recognised and respected as an essential service, and doctors as role models. “Going beyond the call of duty” (stated as “risking one’s life for others” in the survey form), which was perceived as a higher form of commitment or even sacrifice, was probably another reality check and hence was considered inspiring by 35% of students from all years except the interns who were living through this “forced” call of duty with a daily perception of fear of getting or transmitting Covid-19. The sense of ethical duty reflected the core training of the medical profession, and the pandemic provided the opportunity for doctors to fulfil this duty. Altruism and fulfilling a higher purpose were also cited as motivating factors for medical students to care for Covid-19 patients in a study in Brazil [22]. However, a duty to be cared for and to care for oneself was considered equally important ethical imperatives by our respondents. They felt prepared for the risks of handling infectious diseases and were not overly fearful of contracting Covid-19 if protective measures were available. This duty to be protected and of self-care emphasised in the 2017 Physician’s Pledge of the World Medical Association [23] is central to the justice and fairness imperative.

A small proportion of participants across the years as well as the higher proportion of interns who expressed reduced confidence in their career choice or even regretted their choice of career would need forums to discuss their doubts and concerns. Menon and Padhy suggest setting up of a Covid-19 support cell not only in every hospital but also in every medical college to help counsel healthcare workers and medical students, allowing them to voice their anxieties and uncertainties and have them addressed [12]. Even in Ireland, protecting the psychological wellbeing of healthcare workers for the immediate and long term was a key outcome of a study early in the pandemic [14]. Interns, despite a relatively low participation, had a negative perception of the medical profession compared to students of the other years. This is understandable as they were the only group from this sample on the frontline, directly exposed to hospital work during the pandemic, with mandatory hospital duties as well as Covid-19 duties. This was in line with articles in the media, which reported that interns and junior doctors in India considered themselves “cannon fodder” in the treatment of Covid patients [24]. We found that direct exposure to Covid-19 cases was significantly associated with a negative perception towards the medical profession. A study with the interns and junior doctors focusing on the impact of their experiences on their mental health, moral distress, lessons learnt on medicine, healthcare systems, their coping and possible burn out, would be valuable. A study done around the same time among nurses in training placed in Covid wards in Belgium, also found them to have doubts about their choice of career, their training, their risk of infection and stated the need for more psycho-social support [25].

Final year students and interns were concerned about gaining adequate clinical competency for future medical practice. They cited reduced clinical exposure to patients due to the lockdown and hospitals being converted to Covid-19 centres as a major reason. Their parents too were concerned about their medical education and the completion of their course. This study showed that family members and friends strongly influenced perceptions of students and interns on their choice of profession. Interns experienced the challenge of uncertainty in patient care, in communicating with them in the light of changing protocols. Hence, incorporating uncertainty in evaluation of clinical reasoning is worth considering [26] as well as practice sessions of virtual interviews with patients and virtual case discussions [27].

The qualitative data provided a deeper, nuanced understanding of the larger structural issues of the healthcare system, both government and private, and how doctors were perceived as the face of either system. Reports of doctors being treated unfairly, targeted or vilified as scapegoats in a faltering healthcare system were distressing and generated anger not just among our respondents but among medical professionals in general [28]. The pandemic provides an opportunity for the public health component of AETCOM (Attitudes, Ethics and Communication) training, recently introduced into the medical curriculum in India [29], to be strengthened using lessons learnt from the pandemic, inadequacies of the healthcare system and issues of justice and health rights. Lessons in ethical triaging and decision-making in these circumstances are essential, especially in low-resource countries [11]. While communication and media interaction are mentioned in the new guidelines for pandemic training by the National Medical Commission [30], there is an additional need to build advocacy skills, avenues for health systems research, public engagement skills, and opportunities to volunteer with community-based organisations, government programmes and emergency services. The case studies used in such training could include articles from the press as well as experiences, observations and reflections of doctors and patients. Students have also used reflective narratives as a coping mechanism during the pandemic [31]. Students and interns expressed extreme distress at the aggressive behaviour of the public, particularly younger medical students who had not been exposed to this backlash on such a scale before.

Another facet brought out by this study was the lack of learning opportunities that medical students had related to the pandemic and its various consequences. A few students mentioned that volunteering with community organisations helped cope with their disconnectedness from the medical system; while others described their “boredom” or “anxiety” caused by the uncertainty of their futures and unpreparedness for exams. Over-emphasis on examinations and marks meant that students did not consider the pandemic a good learning experience. In contrast, medical students in certain countries sought other opportunities to contribute to healthcare systems and communities with activities ranging from Covid testing and contact tracing to PPE acquisition to developing education material for peers or community workers [32]. Stepping out of the mould of a medical student and being a responsive citizen and citizen leader has important policy implications in the time of a pandemic. Enabling such responses would go a long way in building future “citizen doctors” [33]. The pandemic highlighted the fact that health, medicine and healthcare are integral societal issues and doctors need to be embedded within larger systemic solutions.

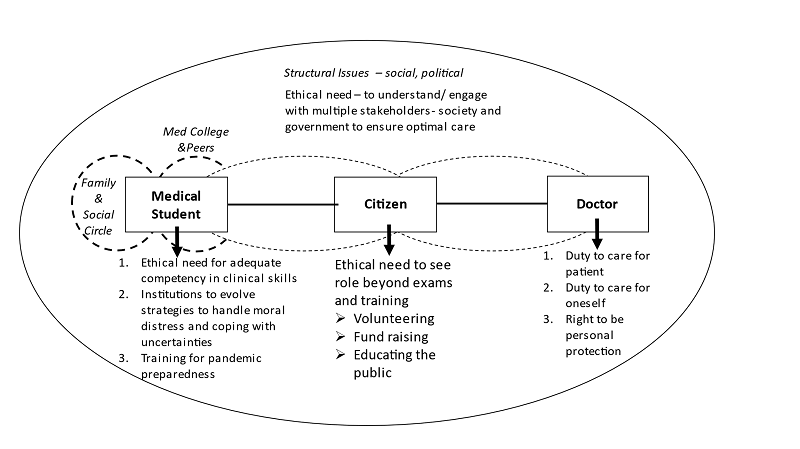

Figure 1: The ethics of responsiveness in medical training in a pandemic

Figure 1 brings together the multiple facets of ethical issues that emerged from this study, grouped under the broad theme of the “Ethics of Responsiveness”. This model recognises that the medical student in training assumes multiple roles; a primary role of a student but also that of a citizen and a doctor. Across these roles, the framework of an ethics of responsiveness requires that:

1) Students assume the responsibility of their education through personal commitment, lobbying for responsive and innovative programmes that reinforce the competencies of medical education;

2) Students as citizens, recognise that health professionals are not apart from the society they serve and need to be embedded in the requirements of society as a part of the solution, beyond providing curative care;

3) Students as doctors practise ethical medicine in constrained situations.

This model does not see the student doctor in isolation but as part of a larger system; so, the ethics of responsiveness requires interventions of change at multiple levels and for multiple stakeholders to respond — not only to the immediate exigencies of the pandemic but to the structural issues in healthcare and in medical education. The essential service role of doctors with its required competence, care and ethics cannot be assumed or expected without the investment in the making of the future doctor through more experiential, socially embedded medical education with skills of understanding the public, responding to them and being the advocate and watchdog for equitable and optimal care. The “Ethics of Responsiveness” can serve as a module in the training of healthcare professionals in preparedness for future pandemics.

Limitations

This study was conducted in only two private medical colleges during the first wave of the pandemic in India. A third government medical college was unable to process formal institutional and ethical approval during the period of data collection as it was a major designated Covid centre in the state. Experiences in government-run centres could be different due to higher workload and even greater constraints on resources. The validity of the survey tool could have been improved by preceding the survey with a phase of formative research that could have thrown up more variables to include in the study and thus reduce the biases of researchers and experts that possibly influenced the tool. The interns in this study were relatively few, but the significant difference in response supports the need for further study of this group along with young doctors.

Conclusion

Despite the calamitous nature of the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic that hit India in 2020 and its unprecedented impact on health workers and the health system, 91.4% of the 900 medical students who participated in the study remained confident of their career choice.

The pandemic has been an eye-opening event, laying bare the risks of the profession and centring the ethics of service and duty to care. Gaps were identified in medical and ethical training particularly regarding uncertainties and coping with deficiencies of the health system as encountered in the pandemic. The essential role played by doctors with its required competence, care and ethics cannot be assumed or expected without investment in the making of the future doctor through more socially embedded medical education imparting the skills of understanding the public, responding to them and being the advocate for their equitable and optimal care. The “‘ethics of responsiveness”’ emerges as important towards preparedness for future pandemics.

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements: The study was supported by the Division of Health and Humanities, St John’s Research Institute, Bengaluru and covered the costs of audio data transcription. Dr Mario Vaz, former head of the Division of Health and Humanities, is thanked for the idea of doing this study and for his valuable inputs while reviewing the final manuscript.

References

- United Nations News. COVID-19: Lockdown across India, in line with WHO guidance. UN News. 24 Mar 2020. [Cited 2022 Aug 08] Available from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/03/1060132

- Tandon A, Roubal T, McDonald L, Cowley P, Palu T, de Oliveira Cruz V, et.al. Economic Impact of COVID-19: Implications for Health Financing in Asia and Pacific. Health, Nutrition and Population Discussion Paper. World Bank, Washington, DC. 2020. [Cited 2021 May 25] Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34572

- Lacina L. What’s Needed Now to Protect Health Workers: WHO COVID-19 briefing. World Economic Forum. 2020. [Cited 2021 May 26] Available from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/10-april-who-briefing-health-workers-covid-19-ppe-training/

- Chauhan C. Covid-19; Disaster Act invoked for the 1st time in India. Hindustan Times. Mar 25, 2020. [Cited 2021 May 25] Available from: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/covid-19-disaster-act-invoked-for-the-1st-time-in-india/story-EN3YGrEuxhnl6EzqrlreWM.html

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Advisory for Hospitals and Medical Education Institutions. March 2020. [Cited 2021 May 26] Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/AdvisoryforHospitalsandMedicalInstitutions.pdf

- McMahon DE, Peters GA, Ivers LC, Freeman EE. Global resource shortages during COVID-19: Bad news for low-income countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020 Jul 6;14(7):e0008412. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008412

- Timms O. Coronavirus: Doctors Sans Safety, Frontline Health Professionals at Risk. Deccan Herald. Apr 24, 2020. [Cited 2021 May 26] Available from: https://www.deccanherald.com/opinion/main-article/coronavirus-doctors-sans-safety-829495.html

- Bhattacharya P, Banerjee D, Rao TS. The “Untold” Side of COVID-19: Social Stigma and its Consequences in India. Indian J of Psych Med. 2020; 42(4), 382-386.

- Yadav S. National Security Act invoked against four Indore residents for ‘attacking’ healthcare workers. The Hindu. April 3, 2020. [Cited 2021 May 26] Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/nsa-invoked-against-four-indore-residents-for-attacking-healthcare-workers/article31242314.ece

- Robert, R., Kentish-Barnes, N., Boyer, A. et al. Ethical Dilemmas Due to the Covid-19 Pandemic. Ann Intensive Care. 2020 Jun 17;10(1):84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00702-7

- Maves RC, Downar J, Dichter JR, et al. Triage of Scarce Critical Care Resources in COVID-19, An Implementation Guide for Regional Allocation. Chest. 2020 Jul;158(1), 212–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.063

- Menon V, Padhy SK. Ethical Dilemmas faced by Health Care Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic: Issues, Implications and Suggestions. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Jun;51:102116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102116

- Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, et al. The Mental Health of Medical Workers in Wuhan, China Dealing with the 2019 Novel Coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Mar;7(3):e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X

- Ali S, Maguire S, Marks E, Doyle M, Sheehy C. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers at acute hospital settings in the South-East of Ireland: an observational cohort multicentre study. BMJ Open. 2020; 10(12), e042930. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042930

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, Ho RC. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(5):1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729

- Khalil R, Mansour AE., Fadda WA. et al. The Sudden Transition to Synchronized Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Study Exploring Medical Students’ Perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2020; 20, 285. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02208-z

- Jothula KY, Ganapa P, Sreeharshika D, Navya K et al. Study to Find Out Reasons for Opting Medical Profession and Regret after Joining MBBS Course among first year students of a medical college in Telangana. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2018; [S.l.], v. 5, n. 4, p. 1392-1396, ISSN 2394-6040. [Cited 2021 May 27] Available from: https://www.ijcmph.com/index.php/ijcmph/article/view/2827/1898.

- Pruthi S, Pandey R, Singh S, Aggarwal A, Ramavat A, Goel A. Why does an undergraduate student choose medicine as a career? Natl Med J India. 2013 May-Jun;26(3):147-9. PMID: 24476160.

- Doulougeri K, Panagopoulou E, Montgomery A. (How) do medical students regulate their emotions? BMC Med Educ. 2016; 16, 312. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0832-9

- Perni S. Moral Distress: A Call to Action. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(6):533-536. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.6.fred1-1706

- Kim K, Lee YM. Understanding uncertainty in medicine: concepts and implications in medical education. Korean Journal of Med Education. 2018 Sep; 30(3), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2018.92

- Tempski P, Arantes-Costa FM, Kobayasi, R, Siqueira M, Torsani MB, Amaro B, Nascimento M, Siqueira SL, Santos IS, Martins MA. Medical students’ perceptions and motivations during the COVID-19 pandemic. PloS One. 2021 Mar 17; 16(3), e0248627. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248627.

- Medical Reporters Today. WMA Amends Hippocratic Oath, Adds Self-care. 2017. [Cited 2021 May 27] Available from: https://medicalreportertoday.com/wma-amends-hippocratic-oath-adds-self-care/

- Mehrotra N, Ghosal A. ‘Cannon fodder’: Medical students in India feel betrayed. Associated Press News. 2021, April 28. [Cited 2021 May 26] Available from: https://apnews.com/article/health-india-new-delhi-coronavirus-b70d05eb020b3e6331863e685fb374fa

- Ulenaers D, Grosemans J, Schrooten W, Bergs J. Clinical placement experience of nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2021 Apr;99:104746. https://doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104746

- 26. Cooke S, Lemay JF. Transforming Medical Assessment: Integrating Uncertainty into the Evaluation of Clinical Reasoning in Medical Education. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2017; 92(6), 746–751. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001559

- Kapila AK, Farid Y, Kapila V, Schettino M, Vanhoeij M, Hamdi M. The perspective of surgical residents on current and future training in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg 2020 Aug; 107(9):e305.https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11761

- The Quint. Assam Doctor Thrashed by Kin of Deceased COVID Patient, 24 Held. 2021 Jun 2 [Cited 2021 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.thequint.com/coronavirus/family-of-deceased-covid-patient-assault-assam-doctor-24-arrested

- Medical Council of India. Attitude, Ethics and Communication (AETCOM) Competencies for the Indian Medical Graduate. 2018 [Cited 2021 Jun 5]. Available from: http://www.mlbmcj.in/ug_curriculam_guide_2019.pdf

- Medical Council of India. Module on Pandemic Management 2020 Aug [Cited 2021 Jun 5]. pp 1-81. Available from: https://www.nmc.org.in/MCIRest/open/getDocument?path=/Documents/Public/Portal/LatestNews/Pandemic-MGT-Module-UG.pdf

- Vaz M. Reflective narratives during the Covid pandemic: an outlet for medical students in uncertain times. Indian J Med Ethics. 2022 Jan-Mar;VII(1):1-4. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2021.048

- Guragai M, Achanta A, Gopez AY, et al. Medical Students’ Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experience and Recommendations from Five Countries. Perspect Biol Med. 2020;63(4):623-631. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2020.0051

- Hegde R, Vaz M. The making of a “Citizen Doctor”: How effective are value-based classes? Indian J Med Ethics. 2020 Jul-Sep; 5(3) NS: 227-35. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2020.055