COMMENT

Resetting outcome targets of community surgery camps: the case of the Chhattisgarh tragedy

Amitabh Dutta; Shyama Nagarajan; Prabhat Choudhary

DOI:10.20529/IJME.2020.018Abstract

State-driven community surgery camps have been organised in India for nearly five decades. Despite their being extremely beneficial to people not having ready access to surgical healthcare (SHC), they continue to be mired in controversies because of negative consequences following free surgery, eg blindness following cataract surgery; infection/death following tubectomy/vasectomy. The onus of complications during and following surgery camps is commonly ascribed to deficient camp infrastructure/facilities. However, the contribution to the problem of the tendency to aim for high-frequency targets in a short time continues to escape public scrutiny. Ironically, even the significant and multiple morbid events during surgery camps only evoke a transient public outcry, reflective professional criticism, hypermedia whimpers, and legal turbulence; before fading completely from public memory. This viewpoint piece, by taking into consideration the various ethical burdens that assail community surgery camps (13 deaths in the Chhattisgarh tragedy of 2014, as a case in point); aims to deconstruct inadequate SHC systems and conflicted surgery targets seeking promotion and fame. It also suggests remedial measures to address the problems, especially in terms of identifying a valid end-point for successful surgery, ie surgery completion or surgery outcome; and how the media, polity, professional fraternity, and executives could reorient themselves to respond more sensitively to problems, for the benefit of the patients and community at large.Keywords: community, surgical camps, system, surgery, reporting, mishaps

Background

The Chhattisgarh tragedy of November 2014, had left 13 women dead and over 70 critically ill after undergoing laparoscopic tubectomy at a state-run birth control camp (1). Post-surgery, the affected women had complained of severe pain in the abdomen, cramps, vomiting, a sinking feeling, and presented to emergency in shock with renal shutdown. The Government ordered a state enquiry into the unfortunate episode. The lead surgeon was apprehended for alleged acts of commission and possible errors of omission (2). The tragedy attracted sharp reactions from the community, the medical profession and civil society groups alike. However, none offered any constructive criticism with remedial potential. The intensity of critical analysis and related considerations dwindled with time and gave way to random social debates and political opportunism. Interestingly, an eminent surgeon’s post hoc take on “who-is-a-good surgeon” opened up a hitherto untouched line of thinking on surgical healthcare delivery (SHCD) (3). He came down heavily on surgeons who rely on their speed in completing surgical operations to claim fame and do not care to wait for the final surgical outcome.

The correlation between “successful surgery” and “surgical outcome” is delicately balanced on a pivot; with the surgeon-dominated definition of a procedure on the one side, and on the other, the patient-outcome, ie the post-surgical functional rehabilitation of the patient. Ironically, while the notion of a “successful” operation tends to be surgeon-inclined and draws more from surgical performance highs, and probably also from uneventful “early” recovery and discharge; the long-term follow up to underscore the real outcome, ie medical success in facilitating the patient’s return to normal life, is totally disregarded. The effective management of even a simple morbidity following surgery is difficult in a community surgery camp because of the uncontrolled environment outside the operation room, involving makeshift arrangements and inadequately trained paramedical support staff. Therefore, difficulties with managing the postoperative component, ie identifying, reporting, and responding to emergent post-surgery problems; preclude end-to-end control of the SHCD process and with it the concept of surgical success based on the final patient outcome.

This paper aims to assess whether, within the SHCD expanse, moving the threshold for “surgical success” from the time of “surgery completion” to “final patient outcome”, holds the key to prevention of similar future catastrophes and presents a mirror to the policy makers and enablers of surgical/medical camps

The history

India has the oldest surgical/medical “camp” system in the world (4). Typically, surgical camps undertake mass surgery for the benefit of communities deprived of surgical care for a host of reasons, including inaccessibility of medical care, inadequate surgical infrastructure; and for purposes such as: achieving state targets of birth control , “corrective” (cleft lip/palate repair, club foot correction), and “therapeutic” surgeries (cataract surgery), among others. Typically, once the surgical camp site is scheduled, the state’s healthcare unit moves in, stations itself at a primary healthcare set up or in the nearest district hospital, re-organises the local medical system to create an optimal environment (eg sterile equipment, theatre) for surgery, gets as many patients operated as possible, and moves out leaving the local medical authority to oversee the follow up. What started as the Government of India’s population control strategy in its first five-year plan (1951) with its first male sterilisation (vasectomy) camp in Ernakulam, Kerala in 1970 (4), gained momentum over time to become a significant component of the state initiative to apply a target-oriented approach to population control. Over the next four decades, these camps evolved and expanded their scope: transitioning from male vasectomy to female tubectomy; from targeted to non-targeted objectives; and from the random surgery camp system to one based on Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) (5).

A critical overview suggests that although the changes may have been intuitive and virtuous to begin with, and directed at upgrading the system’s effectiveness and efficiency for patient safety; they were unable to fulfil the serial micro-targets while ensuring the patients’ well-being. Further, in the absence of any mechanism to identify its benefits, the surgical camp system struggled to incorporate accountability and garner public faith. Thus, the community surgery camp system, though sustainable, continues to draw unfavourable criticism, arouse socio-political conflict, and stimulate reflex media responses. Among other problems, these surgery camps are riddled with human resource challenges like shortages of paramedical personnel to manage patient attendees and surgeons; and the unwanted media sensationalism around the morbid/extreme outcomes. In all this mayhem ─ of organising such extensive camps and managing the expectations of healthcare providers, people, and media ─ nowhere was the surgical outcome specifically scrutinised and assigned a core position so as to instil proactive corrective measures.

The SHCD Challenge

Literature review has suggested that the following aspects merit consideration to analyse “surgical outcome” and redirect the debate towards system-oriented SHCD, to achieve clinically relevant end-points.

First, in a community set up, the relative vulnerability of the patients and their attendants involves a serious ethical burden; including possible violation of autonomy, eg no genuine informed consent, coercion to participate (6), incentives acting as “inducements”, and maleficence in the form of surgical complications, infection, lack of follow-up and medical support; thus the SHCD process is set to fail at its very outset.

Second, often the community surgery programme schedule and functioning unduly stretches the surgeons beyond their professional capacity primarily because:

• the patients do not “walk-in” to see the surgeon individually, they come in en masse;• the surgeons have no control over the type of patients being enrolled;

• there is a skewed surgeon-patient ratio (1:25-100)1; and

• the surgeons are made to operate within a tight schedule (fly-in→operate→leave) that lacks any individualised post- operative care plan.

Paradoxically, surgeons, as in the Chhattisgarh tragedy (1, 2), despite being aware of the potentially negative impact and their professional responsibility and credibility, are allured by incentives and publicity. In fact, the Chhattisgarh surgeon had been the recipient of a State government award (7).

Third, although the “non-surgical” aspects of SHCD, like preoperative patient preparation, post-operative rehabilitation, and supportive medical care is very important in contributing significantly to the surgical outcome; it is generally overlooked in favour of the “operative” component, and gets compromised. The failure of the Chhattisgarh surgical camp is a case in point as to what ailed the “non-operative” SHCD; including the dearth of trained personnel ─ nurses, operating room technicians, anesthesiologists ─ and infrastructure (inadequately sterilised instruments, spurious drugs, among others) (2). This necessitates a refocus on the entire continuum of care of the SHCD process.

The communication challenge

The significance of the media as a communication partner to the government to cover mass surgical camps seems contradictory to the concept of SHCD. In the aftermath of the Chhattisgarh tragedy, unlike the previous failures to reflect on public health debacles (8), possibly politically motivated selective media activism accounted for much hue and cry and criticism from the community. While the media house-arranged discussions focused around the negative fallout of the community surgery camps and highlighted the social fallout of the extreme outcome, they failed yet again to get to the bottom of the problem to portray to the public what could be considered as an adequate care-continuum; and that a “good” surgical outcome hinges on a robust and well executed SHC delivery.

The exposure challenge

Assessment of the actual surgery outcome and how it alleviates patients’ suffering and enhances their quality of life requires close post-operative follow-up. However, in surgery camp settings, this well-established position gets defeated due to the media-polity nexus seeking quick TRPs and political mileage; and the surgeon-bureaucrat combine seeking adequate arrangements and speedy execution. The Aravind Eye Institute and Smile Train International are excellent exemplars of mass surgery access for the very poor (9, 10); and have been able to sustain their successful run because of the absence of intent to advertise, endorse, and disseminate. In their systems, each and every beneficiary patient becomes a champion in spreading the good work. On the contrary, in the Government-backed community surgery settings, the unnecessary premature media hype shifts the focus from the surgical contention such that it instills false confidence in the operating surgeons and emboldens them towards surgical adventurism.

The desire to shorten the journey from being good to becoming great entangles the surgeons on several occasions into creating records to catalyse dissemination of their “pseudo-success” for a variety of motives (11, 12). Mass surgery settings, like the infamous Chhattisgarh episode, tempt opportunistic surgeons to get billed as the fastest, grandly neglecting the impending risks including infection from compromising instrument sterilisation time; anaesthesia complications due to a single anaesthesiologist for many patients; and inadequate postoperative nursing care, and infrastructural compromises arising from too few beds forcing patients to lie on the floor (1, 2, 13).

The way forward

In order to take comprehensive control of SHCD in mass surgery settings, advocacy around final surgical outcome as a central focus seems to be the way ahead. Towards this end, there is need to consider:

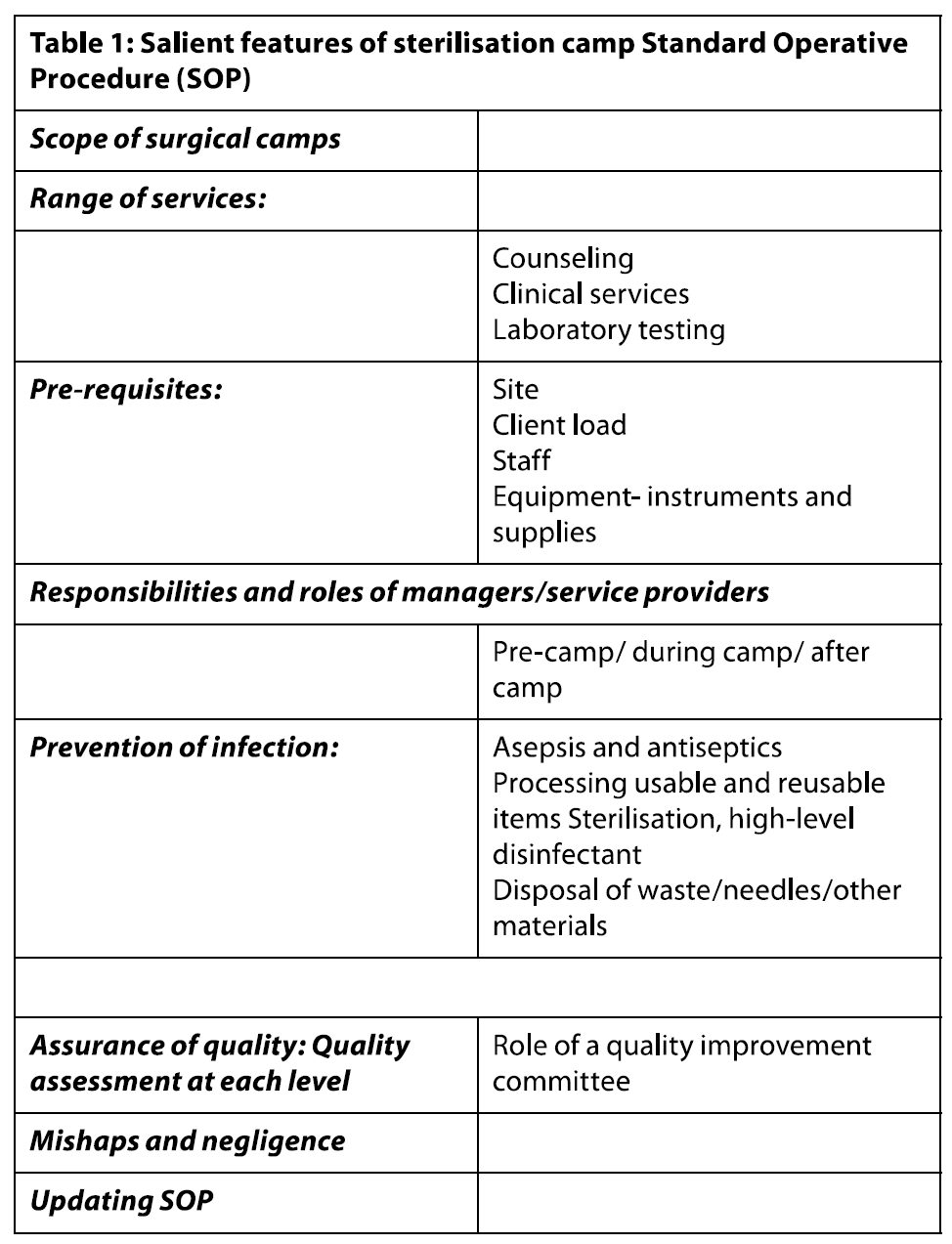

a) Developing a quality assessment module (Table.1) (5), with clear outcome-analysis mechanisms that target the retrieval of information on surgical outcomes from: i) surgeons’ outcome auditii) active tracking and long-term reporting by local healthcare workers over the period of complete internal healing in the community

iii) patient feedback/e-feedback (WhatsApp, Facebook, etc). This may be “passive”, as when the patient reports the outcome on himself/herself; or “active”, when information is gained actively by giving incentives.

b) Setting up dedicated post-camp access that facilitates a positive surgical outcome by offering post-surgery medical consultation, essential medicines, rehabilitation, and healthcare counseling.

c) Balancing the COI-induced inter-principle ethical burdens of the major stakeholders which mass surgical camps are riddled with (11):

• While policy makers seek to uphold the utilitarian (maximum benefit for maximum people) imperatives of surgery camps in consonance with the principle of justice to gain popularity, they completely ignore the principle of respect for patient autonomy (disseminating information, studying patient needs, shared decision making).

• The surgeon and the SHCD team, in the guise of giving the benefits of his/her expertise to the largest possible number of patients (principle of beneficence), work to seek early promotions, laurels and recognition. Also, operationalising the expansive surgery list in a very short time, these camps stand to severely undermine the principle of non-maleficence because of the increased probability of surgical and post-operative complications.

• Ironically, the patients, the most important stakeholders of a mass surgery camp, in their desperation to get free treatment near their homes, are predisposed to compromise on their autonomy despite the greater risk of complications in settings where surgery turnover is quick and overall care is suspect.

Therefore, reinstating long-term surgical outcome as the new vantage point for the analysis of impact would better assess the success of surgery, dilute the stakeholders’ conflicts of interest (COI), and improve harmonisation of different ethical principles.

d) Involving private healthcare institutions to include community surgery campaigns in their corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiative: The many private healthcare institutions which have already been carrying out successful surgery camps for decades together should be identified, supported, and recognised for their efforts.e) Cultivating responsible reporting routines that cover every patient from the time of recruitment for surgery to the final outcome in the form of completed camp reports. To sustain public faith in the surgical camp system and justify their position of meaningful and unbiased reporting, the communication media must curb:

• “First-out” instincts on summing up surgical outcome. Considering that there is always a significant time gap between surgical intervention and its therapeutic effect, the reporting system should refrain from a sensational approach.

• Unnecessary glorification of surgeons solely based on the quantum of operations;

• Immediate post-hoc dissection of tragic surgical outcomes in the public domain before investigations are completed.

The media must also invest in proactive comprehensive coverage to disseminate real-time details to the beneficiary community on a public information platform, starting from: closing/opening dates, FAQs, advisory before surgery, and a feedback portal to report outcome/concerns/query.

Key messages

1. To prevent patient morbidity, full control of the SHCD process is of paramount significance and mass surgery camps’ targets, ie number of patients to be operated on at a time, should be commensurate to and align with the available human resource (surgeons, anaesthetists, and support staff) and infrastructure capacity.2. For enhanced patient safety, proactive policy up-gradation is required in the following areas: SHCD capacity building, patient selection ethics, outcome analysis, and responsibility allocation, both individual and collective.

3. In case of inadvertent problems with surgical camp process affecting innocent patients, the communication media including the record resources (newsprint, gazettes, books, report manuals) should invest in scientific analyses and discussions that identify problems and offer solution in the SHCD processes, than in non-domain overtures around probity-legality and politicisation.

4. The recipient community and institutional fraternity including legal and media professionals are advised to take note of the final patient outcome as an index of surgery success and not to get swayed by incomplete and misrepresented public information resources issued by commercial media house(s) that overstate facts for reasons other than the actual outcome, for their own benefit.

Conclusions

In state-backed mass surgery initiatives for the community, the overall responsibility for surgical healthcare delivery rests with the institution, rather than with the individual employed to carry out designated work. Conversely, to ensure patient safety, it is the individuals’ responsibility to undertake the assigned work allocated to them. Therefore, in order to elevate SHCD practices, one needs to move from merely carrying out technical operative procedures to a process serially connected with objectively defined conduct and completion end-points. Finally, a well-defined and robust SHCD system complemented by collective organisational responsibility seems the way forward to positive surgical outcomes and prevention of morbid events associated with community surgical camps.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Nitin Sethi for giving his valuable time for review of the manuscript and suggesting changes/added information.Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.1Note This ratio is based on the first author, AD’s personal experience of community surgery camps

References

- Kaiser E. Chhattisgarh: Sterilization death toll climbs to 11. Raipur, Hindustan Times. 2014 Nov 11[cited 2019 Dec 31]. Available from: www.hindustantimes.com/…news/chhattisgarh…/article1-1284793.aspx

- Deaths put spotlight on India’s sterilization camps. Wall Street Journal. 2014 Nov 13[cited 2019 Dec 30]. Available from: www.wsj.com/…/doctor-detained-for-sterilization-deaths-in-india-1415871780

- Nagral S. The Chhattisgarh tragedy and Indian surgeons’ love for speed. Rediff.com. 2014 Nov 28[cited 2019 Dec 15]. Available from: www.rediff.com/news/column/the-chhattisgarh-tragedy-and-indian-surgeons-love-for-speed/20141128.htm

- Venkatram S. India’s sterilisation camps must give way to proper family planning. The Guardian. 2014 Nov 22 [cited 2019 Dec 30]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2014/nov/22/india-sterilisation-camps-family-planning-tragedy

- Sood R. Standard Operating Procedures: Surgical/Medical Camps. New Delhi: IMA; date unknown [cited 2020 Jan 15]. Available from: https://www.ima-india.org/ima/left-side-bar.php?scid=514

- Das A, Contractor S. India’s latest sterilisation camp massacre. BMJ. 2014 Dec 1; 349.g7282. doi. 10.1136/bmj.g7282.

- Bhatikar T. Why the Chhattisgarh sterilisation tragedy may happen again. India Together. 2014 Nov 24[cited 2020 Jan 22]. Available from: http://www.indiatogether.org/sterilisation-camp-chhattisgarh-counterfeit-spurious-drugs-health

- Pandya SK. A review of the Lentin Commission report on the glycerol tragedy at the J.J. Hospital, Bombay. Natl Med J India. 2007; 1: 144-8.

- Naidoo J. An infinite vision: The story of Aravind Eye Hospital. Daily Maverick. 2012 May 11[cited 2020 Jan 22]. Available from:https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2012-05-11-an-infinite-vision-the-story-of-the-aravind-eye-hospital/

- Gupta K, Bansal P, Dev N, Tyagi SK. Smile Train project: a blessing for population of lower socio-economic status. J Indian Med Assoc. 2010 Nov; 108 (11):723-5.

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia. Professional Standards and Guidelines: Conflict of Interest. June 2010: 1-5.

- Finlayson SRG. How should academic surgeons respond to enthusiasts of global surgery? Surgery 2013; 153: 871-2.

- 13.Pulla P. Why are women dying in India’s sterilisation camps? BMJ. 2014 Dec 8; 349: g7509.doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7509.