RESEARCH ARTICLE

Factors influencing the sustainability of a community health volunteer programme — A scoping review

Sathish Rajaa, Balasubramaniam Palanisamy

DOI: 10.20529/IJME.2022.079Abstract

Background: Sustainability of any Community health worker programme is determined by several internal and external factors and is highly context and region specific. We aimed to identify factors that influence the sustainability of a community health volunteer programme across the globe.

Methods: We conducted a scoping review using the Arksey and O’Malley framework. From four major databases, we extracted qualitative and quantitative peer-reviewed studies published in the English language, from January 2000 to March 2022, that reported on factors influencing sustainability of a community volunteer programme. We adopted a narrative synthesis form to report our findings.

Results: Our search strategy yielded 1086 citations, of which 35 articles were finally included for the review after screening for eligibility. The studies included in our review reported an attrition rate ranging from 9 to 53%. The crucial factors that played a decisive role in sustainability included sociodemographic and sociocultural factors, trust, incentives, identity and recognition, sense of belonging, family support and other programme-related factors.

Conclusion: Our study found that several complex personal and social factors affect the community health volunteers’ performance, thereby impacting the scaling up of a community volunteer programme. Efforts to address these factors would aid policy makers to successfully sustain a volunteership programme in resource-poor settings.

Keywords: community health volunteer, volunteerism, sustainability, scoping review, scale up

Introduction

Community participation is one of the important components of primary healthcare, as per the Alma Ata declaration, 1978 [1]. In recent years, many countries have expanded their health systems by training community health volunteers (CHVs) on a large scale [2, 3]. The World Health Organization has defined community health volunteers as healthcare providers who serve the community in which they live, and receive lower levels of formal training and necessary education than a professional healthcare worker such as nurses and doctors [4]. Studies done in several countries add to the existing evidence that CHVs can contribute significantly to the betterment of varied health outcomes [5, 6, 7, 8]. This process of involving the community in implementing health programmes neutralises health inequalities by positively impacting social capital and social cohesion [9]. Despite their effective contribution, much of the literature is relevant only in developing countries, especially in those lacking adequate healthcare access [10].

Furthermore, CHV performance is context-specific and is linked to several internal and external factors. Despite the crucial role played by the CHVs, retention and sustainability of an effective CHV model have always remained a challenge for several public health interventions. Previous literature has documented that supervision, efficient and effective training, community appreciation for the efforts made, and family support have influenced sustainability to a greater extent [9, 10]. Globally, several CHV-led programmes have reported attrition rates ranging from 3.2% to 77%. [11, 12] Such high attrition rates have raised questions about the relationship between the volunteers and the community and increased the chances of a lost opportunity to effectively use the workforce.

Shah et al identified two forms of volunteerism — formal and informal. Formal volunteerism is done with the help of a group or an organisation and is often structured and embedded inside a community-based organisation or a non-governmental organisation (NGO), while the latter is delivered by an individual to render service to the community [13]. The term “health volunteerism” is the foundation for every CHV model that is often exploited. CHV often decide to volunteer with the intention to support health systems and enhance health literacy of the community and self, and often require constant support from the health system [14]. Furthermore, the concept of volunteerism is itself a complex phenomenon that involves self-motivation, but is determined by several social and psychological determinants. Thus, it is necessary to understand the importance of the internal characteristics of both types, and external social and political influences before implementing them in the community. To bridge this gap, we decided to undertake this review to identify factors that influence the success and sustainability of a Community Health Volunteer programme.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review using the Arksey and O’Malley framework [15].

Identifying the research questionWhat factors influence the success and sustainability of a Community Health Volunteer programme?

Identifying relevant studiesAn extensive search in PROSPERO and Cochrane was done to ensure that no similar review protocol has been reported. This scoping review was done by including all the available evidence exploring the sociodemographic, ethical, economic, and other social factors that influenced the sustainability of an effective CHV model.

Search strategyA comprehensive and systematic search in databases and search engines such as MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar for literature from January 2000 to May 2022 was done [Supplementary file 1]. In addition, reference lists of primary studies were checked to include more articles relevant to our review. Our literature search was restricted to the period from January 2000 to May 2022, as a prior review by Prasad and Muraleedharan in 2007 had discussed the profile of CHVs, the health outcomes of CHV-run programmes, and organisational issues that influenced the performance of CHVs [16]. Their review highlighted crucial factors such as the selection process of CHVs, their educational status, lack of adequate training, lack of remuneration and supportive supervision, which influence CHV performance [16].

Study selectionBoth qualitative and quantitative peer-reviewed studies published in the English language were included in the review. Supporting evidence from other mixed methods studies was also screened for its eligibility and was included. In addition, studies using qualitative techniques for data collection such as focus group discussion (FGD), in-depth interviews (IDI), and Key Informant Interviews (KII), were included. Studies from books, conference abstracts and other unpublished literature were excluded.

Outcome assessmentWe set out to understand the various factors that influenced the sustainability of the CHV model.

Data extraction and managementAfter the study selection, the principal investigator scrutinised the extracted data and retrieved the study characteristics in a predetermined data extraction format. Data entry was also double-checked for accuracy. The necessary information was extracted from the included studies.

Quality assessmentRisk of bias assessment of individual included articles was not undertaken, as it was not consistent with the requirements of a scoping review [17].

Data analysisWe adopted a narrative synthesis form of data analysis, and represented all data qualitatively (content analysis) and quantitatively (frequency analysis) for the conduct of this scoping review. The information obtained was analysed independently by both authors and subsequently compared and collated with other study findings using an integrated knowledge translation approach [18, 19].

Results

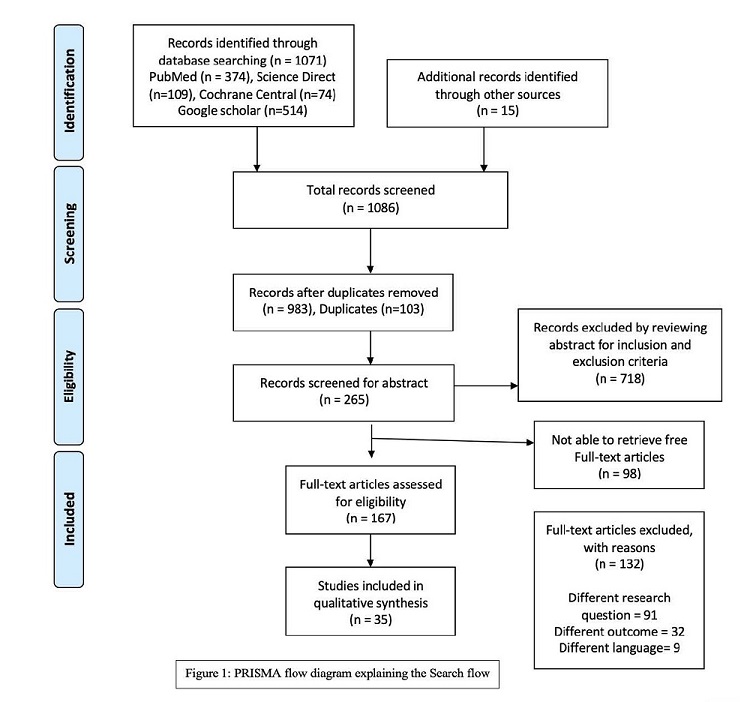

Literature searchThe search strategy yielded around 1086 citations, of which 103 were duplicates. Of the remaining 983 articles, 718 were excluded after initial screening for the title, keywords and abstract. Of the remaining 265 articles, 98 were not retrieved as their free-full text version was not available. The remaining 167 articles were subjected to secondary screening, of which 132 were excluded (91 as they answered a different research question, 9 as they were not in the English language, and 32 as they reported outcomes other than the sustainability of the CHV model). Finally, 35 articles were included for the final scoping review [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54]. Figure 1 explains the study selection process and study flow. Table 1 [available online only] presents the general characteristics of the included studies.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram explaining the search flow

Sustainability is defined in literature as “the degree to which an innovation continues to br used after the initial efforts to secure them are completed” [20]. A few studies have also tried to quantitatively estimate sustainability as the persistence of any programme or intervention more than a year after research or implementation is complete [10, 41]. Through our review, we observed that 11/35 (31%) studies reported attrition rates, among which the rate of attrition varied between 9-53% across various study settings.

All studies included in the review either used qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods approaches to evaluate the factors that influence sustainability. The major drivers that influenced the sustainability of their work included:

Sociodemographic factorsPersonal characteristics such as age, gender, occupation, marital status, and education act as crucial internal factors that play a pivotal role in the sustainability of motivation from within [38]. Studies have shown that attrition is more apparent among women when compared to men, due to family constraints and inability to perform community work beyond certain working hours, or due to a heavy workload [28, 38, 39,50, 51]. A majority of the studies have stated that age is an important factor that contributed to sustainability; ie, more volunteers above 40 years tend to remain in the programme as compared to young adults who tend to drop out owing to other commitments [10, 33, 38]. Quantitative results have shown that married individuals tend to stay in the volunteer programme despite their commitments. Retention rates were higher among the educated and those employed in the unorganised sector when compared to the salaried organised sector [39]. This reflects the constraints faced by volunteers holding a job while also spending time in community work. Studies also observed higher retention rates among men and women who are married [32,41].

Lack of incentivesA majority of the studies reported lack of financial incentives as an important determinant of sustainability of a CHV model. This proves that the term “volunteer” does not wholly translate into free work. The CHVs who render services to the communities outside their working hours expect a basic remuneration to keep them motivated. [22, 24, 29, 31, 36, 42, 45, 47, 48, 49, 50]

Serving one’s own community (Belonging)Studies have stated that the selection of CHVs outside the community or outside the already existing community-based organisations (CBO) makes the model more volatile and vulnerable. Volunteers, when selected from the local community, tend to have a better understanding of the community [20, 21, 25]. Choosing or preferring volunteers from already existing CBOs will give a sense of accountability, ownership, and the opportunity to establish networks [23,24, 26,42, 46].

Conflicting responsibilities and time managementStudies have shown that in certain settings, the line drawn between volunteering and conditional expectations from the health staff fails to exist. Sometimes, the volunteers are overstretched and expected to work beyond their free time affecting the quality of their work and satisfaction. In a few instances, studies have reported that CHVs had to forgo their family time or daily chores for rendering community services. Such practices might impede satisfaction that a CHV is expected to gain from volunteering [21, 33, 40, 47].

TrustChoosing CHVs from among individuals already established in the community for volunteering services increases the level of trust that the community has in the volunteers. This trust would enable the CHV network to establish a strong bond between the community and the health team, which might in turn enhance the accountability and sustainability of the programme [25, 27, 28, 29, 42, 44, 45].

Family supportStudies have identified family support as one of the vital determinants of sustainability of a CHV programme. Support from spouse, children and other family members are essential drivers that influence not just the effectiveness of services rendered, but also long-term sustainability and even the phenomenon of “volunteering” as a whole [31, 34, 35].

OpportunitiesA few CHVs have also expressed their hope that future opportunities like preference in government posts or local village jobs open up through this CHV participation [23, 30, 32, 42].

Sociocultural barriersCHVs have also stated that it becomes difficult for them to forgo daily routines, childcare, attending important social and family functions for community-related work, thereby forcing them to either allot little time for community work or withdraw from the organisation [36, 37,45]. A few studies have also added transportation as a major concern, especially in resource-poor settings, where they are forced to use their own motorbikes for outreach activities. The reimbursement that they receive is either insufficient or delayed [42, 48, 50, 51].

Programme-related factorsThe following programme-related factors play a decisive role in influencing the long-term sustainability of any CHV programme.

a. Selection and coordination: It is necessary to consider if the volunteer has truly volunteered out of their own interest, and if he/she is the right person for a specific health intervention. These criteria need to be looked into for sustaining the activity. Clearer description of roles and responsibilities during the selection of CHV’s and coordination of their day-to-day activities would also facilitate volunteering.

b. Training and retraining: This serves as a basic necessity for any CHV programme. Sensitisation of volunteers to the intervention and pre-interventional training is necessary, not only for sustainability but also for effective implementation and success of the programme [38, 43, 46, 49, 50, 52].

c. Supportive supervision: This is often acknowledged as a crucial lever that ensures the sustainability of any community health intervention and especially that of a community health volunteer model. This enables the volunteers to stay motivated. Recent studies have endorsed supportive supervision as an effective tool to enhance the knowledge, performance, productivity and sustainability of CHVs [44,49, 50, 52, 53] .

d. Accountability: Reporting of services rendered to the community leaders or village health leaders or to the health team makes the CHV accountable to the community. This could always be supplemented with frequent record reviews, monitoring and observations, grievance redressal, and obtaining constructive feedback [41,46,49].

Though they often remain unnoticed, a few studies have documented that the occurrence of vital events in the families of CHVs plays a significant role in sustaining the participation of CHVs in the programme. Any occurrence of key events such as migration, marriage, death or childbirth might influence the volunteer to rethink the decision to continue his/her volunteering for community work [23, 39].

Identity and recognitionBeing granted an identity and recognition are basic requirements for a volunteer programme. In some studies supporting the same, CHVs had expressed their insecurities about continuing in the programme in case they are not granted proper recognition and identity. Volunteers have raised concerns about facing difficulty in carrying out community work without provision of identity cards and labelled T-shirts [27, 32, 43, 45, 46, 51].

SecurityA few studies have shown greater sustainability of CHV programmes where the volunteers were provided with basic security needs such as travel allowance, safe travel, a place to stay to ensure physical safety, provision of basic amenities such as torches, headlights and umbrellas, etc [41,45,51].

Discussion

We undertook this scoping review to gather the available evidence and understand and describe the factors that influence the sustainability of a community health volunteer programme. There is plenty of literature on the effectiveness of CHV programmes; however, research focusing on the long-term sustainability of these programmes, or studies exploring the factors that determined the sustainability or non-sustainability of a particular programme are sparse [37,54]. Sustainability is an inherent component of any community health programme and is a crucial outcome that influences the scaling up of the programme to higher levels. Scaling up of a programme — through additional financial and human resource allocation — is futile when it is not sustainable. Thus, awareness of the key factors influencing sustainability becomes integral to scaling up any community health programme. This could pave the way for policymakers and other stakeholders to identify factors that could substantially influence budgeting, resource allocation and scalability of any pilot or small-scale programme [55]. Our findings are in line with several studies from India that explored the factors motivating the accredited social health activists (ASHAs) [55].

Our scoping review has systematically collated data from various study sources and designs, thereby generating concrete evidence regarding sustainability of CHV programmes. Studies included in our review were neither done in ideal settings nor reported all the necessary information; however, any report on factors influencing the sustainability of a community health volunteer model was chosen to build a construct of determinants [37, 38].

Of late, it is considered that the rights of CHVs need to be assessed and addressed beforehand to ensure full participation of CHVs in any community health programme. These rights include the right to volunteer and withdraw, the right to social recognition, incentivisation, inclusivity, etc [14, 36 , 40]. The importance of personal characteristics (selection criteria), family and community support are well established by several previous studies and reviews [56]. These factors are necessary to keep up the momentum, despite the hardships CHVs face during community work. The sense of job satisfaction and family support is not only crucial for the sustainability of community work but also decisive for volunteering [57].

The wide ranging differences in attrition rates among the included studies could be due to variations in the study settings, nature of work expected, and availability of remuneration, motivation and community support. It was also interesting to observe that sustainability or retention is better when the community-based initiative comes from a well-established organisation or NGOs that have previously been involved in community work. NGOs could serve as resources for mobilising remote communities, empowering and training volunteers, establishing local social relations, providing microfinance or economic support to the volunteers, building capacity and enhancing self-reliance, thereby promoting the sustainability of the model [58]. More CHVs tend to drop out when the attempt is new, or is not long-term, or when there is a lack of leadership and team effort [41, 44, 47].

As stated above, there are a number of variables that affect the CHVs’ capacity to provide effective services. Motivation, is an important determinant in CHV recruitment, retention, and performance, and may even be a determining factor in the delivery of effective services [20]. Provision of incentives or CHV remuneration has always remained a long-standing challenge for many community-based programme implementers and NGOs [58]. Incentives, which can include anything from uniforms, volunteer allowances, and pay [59, 60], might affect motivation, in turn. The relationship between incentives, motivation, retention, and CHVs’ performance has been illustrated by Daniels et al [60]. The kind, extent, and combination of incentives that would increase the motivation of CHVs have been extensively debated. Financial incentives range from allowances for volunteers, and fixed salary for individuals who are formally employed to performance-based rewards. Different studies have shown that the financial support differed for paid employees and volunteers (3 USD to 100 USD) [60]. The second group of volunteers, who were not paid salaries, received tangible rewards such as clothing, health insurance, or work-related equipment like boots and bags. Community recognition, preferential treatment in receiving drugs or during OPD visits in health centres, and support in acquisition of new skills, are examples of non-material incentives. Other possible incentives include bicycles and other modes of transportation, consistent supplies, training opportunities, and supportive supervision. These incentives, which represent the fundamental resources to be made accessible by the health system for CHVs to perform well, are often referred to as “job enablers” [61]. These tangible rewards and job facilitators not only helped them in their work but also boosted the reputation of community health programmes among CHVs and the populations they worked with.

Strengths and limitationsOurs is one among the very few available reviews that focus on personal and social factors influencing the sustainability of a CHV model. We have adopted a narrative synthesis to report our results, after searching for relevant literature in all four major databases. However, in our review, we did not study the effect of various interventions that the CHVs contributed to the sustainability of the model.

Future considerationsA noteworthy point is that the sustainability of a programme is heavily dependent on the need for and the nature of the intervention provided. In case a community health programme is self-reliant through external or internal funding, then remuneration or programme costs will not be an issue, which might take care of the most important reason for attrition, namely the low remuneration. In cases where funding is an issue, the programme needs to have adequate community support, constant motivation and training to make it sustainable. Also, when the need of the intervention is met, it is necessary to re-deploy CHVs to other already existing programmes or train them for a newer objective, rather than dissolving the volunteer group. Further, future research must focus on programme-related factors that would influence the sustainability of the CHV model, an aspect that is often missed. Future research could be strengthened by the use of newer techniques such as Health Technology Assessment and health policy and systems research that would enable policy makers to have a bird’s eye view of the CHV model and its sustainability.

It was also noted that there was significant variability in the definition of attrition used in the limited literature available on CHV sustainability. Different studies used varied definitions to call their model sustainable, which could influence the retention percentage reported in these studies [9, 41]. Thus, our review emphasises the need to have a programmatic definition for defining “retention”, thereby making comparisons possible.

Conclusion

Our study results showed that the sustainability of any CHV programme is a complex process and is determined by several individual-level (trust, sociodemographic factors, incentives, family support), community-level (sociocultural barriers, identity and recognition) and programme-level factors (selection process, training and supervision).

Acknowledgments: We would like to acknowledge the Rural Women’s Social Education Centre team and the Thakur Foundation for the fellowship programme. We would also like to extend our gratitude to all the resource faculty of the writeshop sessions, and the other fellows for their constructive feedback.

Conflict of Interest: Nil

References

- Gillam S. Is the declaration of Alma Ata still relevant to primary health care? BMJ. 2008 Mar 6;336(7643):536-8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39469.432118.AD

- Javanparast S, Windle A, Freeman T, Baum F. Community health worker programs to improve healthcare access and equity: are they only relevant to low-and middle-income countries? Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018 Oct 1;7(10):943. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2018.53

- Asweto CO, Alzain MA, Andrea S, Alexander R, Wang W. Integration of community health workers into health systems in developing countries: opportunities and challenges. Fam Med Community Health. 2016 Jan 1;4(1):37-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.15212/FMCH.2016.0102

- World Health Organization. What do we know about community health workers? A systematic review of existing reviews. Vol. 17. Human Resources for Health Observer Series. 2020(19). [Cited 2022 Sep 26] Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/what-do-we-know-about-community-health-workers-a-systematic-review-of-existing-reviews

- Kironde S, Kahirimbanyi M. Community participation in primary health care (PHC) programmes: Lessons from tuberculosis treatment delivery in South Africa. Afr Health Sci. 2002 Apr2(1):16–23. PMID: 12789110

- Dongre A, Deshmukh P, Garg B. A community based approach to improve health care seeking for newborn danger signs in rural Wardha, India. Indian J Pediatr. 2009; 76 (1) : 45-50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-009-0028-y

- Jacobs C, Michelo C, Chola M, Oliphant N, Halwiindi H, Maswenyeho S et al. Evaluation of a community-based intervention to improve maternal and neonatal health service coverage in the most rural and remote districts of Zambia. PLOS One. 2018 Jan 16;13(1):e0190145. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190145

- Iron-Segev S, Lusweti J, Kamau-Mbuthia E, Stark A. Impact of Community-Based Nutrition Education on Geophagic Behavior and Dietary Knowledge and Practices among Rural Women in Nakuru Town, Kenya: A Pilot Study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018 Apr;50(4):408–14.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2017.10.013

- Argaw D, Fanthahun M, Berhane Y. Sustainability and factors affecting the success of community-based reproductive health programs in rural Northwest Ethiopia. Afr J Reprod Health. 2007 Aug 1;11(2):79-88. PMID: 20690290

- Rajaa S, Sahu SK, Mahalakshmi T. Assessment of Community Health Volunteers contribution and factors affecting their health care service delivery in selected urban wards of Puducherry–A mixed-methods operational research study. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2022 Oct 1:101135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2022.101135

- Nkonki L, Cliff J, Sanders D. Lay health worker attrition: Important but often ignored. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(12):919–923. https://doi.org/10.2471%2FBLT.11.087825

- Bhattacharyya K, Winch P, LeBan K, Tien M. Community health worker incentives and disincentives. Virginia: USAID-BASICS II. 2001 Oct. [Cited 2022 Sep 21] Available from: http://web.worldbank.org/archive/website01539/WEB/IMAGES/PNACQ722.PDF

- Shah J, Saundi T, Hamzah A, Ismail I. Why youths choose to become volunteers: From the perspective of belief. Athens J Social Sci. 2014; 2(1): 51–64. https://doi.org/10.30958/ajss. 2-1-4

- Walker T, Menneer T, Leyshon C, Leyshon M, Williams AJ, Mueller M, et al. Determinants of volunteering within a social housing community. VOLUNTAS: Int J Volunt Nonprofit Organ. 2020 Sep 28:1-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00275-w

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Social Res Methodol. 2005 Feb 1;8(1):19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Prasad B, Muraleedharan V. Community health workers: a review of concepts, practice and policy concerns. A review as part of ongoing research of International Consortium for Research on Equitable Health Systems (CREHS).2007 Aug.

- Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

- Straus SE, Tetroe JM, Graham ID. Knowledge translation is the use of knowledge in health care decision making. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(1):6–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.08.016

- Gagnon M. Knowledge Exchange: Knowledge dissemination and exchange of knowledge. In: Knowledge Translation in Health Care: Moving from Evidence to Practice. Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. p. 233-245.

- Kastner M, Sayal R, Oliver D, Straus SE, Dolovich L. Sustainability and scalability of a volunteer-based primary care intervention (Health TAPESTRY): a mixed-methods analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017 Dec;17(1):1-21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2468-9

- Mallari E, Lasco G, Sayman DJ, Amit AM, Balabanova D, McKee M, et al. Connecting communities to primary care: a qualitative study on the roles, motivations and lived experiences of community health workers in the Philippines. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020 Dec;20(1):1-0. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05699-0

- Glenn J, Moucheraud C, Payán DD, Crook A, Stagg J, Sarma H et al. What is the impact of removing performance-based financial incentives on community health worker motivation? A qualitative study from an infant and young child feeding program in Bangladesh. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021 Dec;21(1):1-1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06996-y

- Mays DC, O’Neil EJ, Mworozi EA, Lough BJ, Tabb ZJ, Whitlock AE, et al. Supporting and retaining Village Health Teams: an assessment of a community health worker program in two Ugandan districts. Int J Equity Health. 2017 Dec;16(1):1-0. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0619-6

- Singh D, Negin J, Otim M, Orach CG, Cumming R. The effect of payment and incentives on motivation and focus of community health workers: five case studies from low-and middle-income countries. Human Resourc Health. 2015 Dec;13(1):1-2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-015-0051-1

- Jigssa HA, Desta BF, Tilahun HA, McCutcheon J, Berman P. Factors contributing to motivation of volunteer community health workers in Ethiopia: the case of four woredas (districts) in Oromia and Tigray regions. Hum Resour Health. 2018 Dec;16(1):1-1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0319-3

- Ritchie MA. Social capacity, sustainable development, and older people: lessons from community-based care in Southeast Asia. Dev Pract. 2000 Nov 1;10(5):638-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520020008814

- Morton T, Wong G, Atkinson T, Brooker D. Sustaining community-based interventions for people affected by dementia long term: the SCI-Dem realist review. BMJ Open. 2021 Jul 1;11(7):e047789. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047789

- Ngugi AK, Nyaga LW, Lakhani A, Agoi F, Hanselman M, Lugogo G, et al. Prevalence, incidence and predictors of volunteer community health worker attrition in Kwale County, Kenya. BMJ Global Health. 2018 Aug 1;3(4):e000750. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000750

- Hobbs AJ, Manalili K, Turyakira E, Kabakyenga J, Kyomuhangi T, Nettel-Aguirre A, et al. Five-year retention of volunteer community health workers in rural Uganda: a population-based retrospective cohort. Health Policy Plan. 2022 Apr;37(4):483-91. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czab151

- Kuule Y, Dobson AE, Woldeyohannes D, Zolfo M, Najjemba R, Edwin BM, et al. Community health volunteers in primary healthcare in rural Uganda: factors influencing performance. Frontiers Public Health. 2017 Mar 29;5:62. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00062

- Abbey M, Bartholomew LK, Nonvignon J, Chinbuah MA, Pappoe M, Gyapong M, et al. Factors related to retention of community health workers in a trial on community-based management of fever in children under 5 years in the Dangme West District of Ghana. Int Health. 2014 Jun 1;6(2):99-105. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihu007

- Ngilangwa DP, Mgomella GS. Factors associated with retention of community health workers in maternal, newborn and child health programme in Simiyu Region, Tanzania. Afr J Primary Health Care Family Med. 2018 May 3;10(1):1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1506

- Rajaa S, Sahu SK, Thulasingam M. Contribution of community health volunteers in facilitating mobilization for nutritional screening among adolescents (10-19 years) residing in urban Puducherry, India – an operational research study. Int J Community Med Public Health 2021;8:4506-12.

- Botta M. Evolution of the slow living concept within the models of sustainable communities. Futures. 2016 Jun 1;80:3-16.

- Olang’o CO, Nyamongo IK, Aagaard-Hansen J. Staff attrition among community health workers in home-based care programmes for people living with HIV and AIDS in western Kenya. Health Policy. 2010 Oct 1;97(2-3):232-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.05.004

- Takasugi T, Lee AC. Why do community health workers volunteer? A qualitative study in Kenya. Public Health. 2012 Oct 1;126(10):839-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2012.06.005

- Winn LK, Lesser A, Menya D, Baumgartner JN, Kirui JK, Saran I, et al. Motivation and satisfaction among community health workers administering rapid diagnostic tests for malaria in Western Kenya. J Global Health. 2018 Jun;8(1). PMID: 29497500

- Daniels K, Sanders D, Daviaud E, Doherty T. Valuing and sustaining (or not) the ability of volunteer community health workers to deliver integrated community case management in northern Ghana: a qualitative study. PloS one. 2015 Jun 16;10(6):e0126322. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0126322

- Chatio S, Akweongo P. Retention and sustainability of community-based health volunteers’ activities: A qualitative study in rural Northern Ghana. PloS one. 2017 Mar 15;12(3):e0174002. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174002

- Rajaa S, Sahu SK, Thulasingam M. Contribution of community health care volunteers in facilitating mobilization for diabetes and hypertension screening among the general population residing in urban Puducherry–An operational research study. J Family Med Primary Care. 2022 Feb;11(2):638. https://doi.org/10.4103%2Fjfmpc.jfmpc_1316_21

- Chen HL, Chen P, Zhang Y, Xing Y, Guan YY, Cheng DX. et al. Retention of volunteers and factors influencing program performance of the Senior Care Volunteers Training Program in Jiangsu, China. PloS one. 2020 Aug 10;15(8):e0237390. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237390

- Dieleman M, Cuong PV, Anh LV, Martineau T. Identifying factors for job motivation of rural health workers in North Viet Nam. Hum Resour Health. 2003 Nov 5;1(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-1-10. PMID: 14613527

- Low A, Ithindi T. Adding value and equity to primary healthcare through partnership working to establish a viable community health workers’ programme in Namibia. Crit Public Health. 2003 Dec 1;13(4):331-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581590310001615871

- Mishra A. ‘Trust and teamwork matter’: community health workers’ experiences in integrated service delivery in India. Glob Public Health. 2014;9(8):960-74. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.934877. Epub 2014 Jul 15. PMID: 25025872.

- Lusambili M, Nyanja N, Chabeda V, Temmerman M, Nyaga L, Obure J, et al. Community health volunteers challenges and preferred income generating activities for sustainability: a qualitative case study of rural Kilifi, Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021 Dec;21(1):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06693-w

- Handley M, Bunn F, Dunn V, Hill C, Goodman C. Effectiveness and sustainability of volunteering with older people living in care homes: A mixed methods systematic review. Health Soc Care Community. 2022 May;30(3):836-855. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13576. Epub 2021 Sep 24. PMID: 34558761.

- Hanson HM, Salmoni AW. Stakeholders’ perceptions of programme sustainability: findings from a community-based fall prevention programme. Public Health. 2011 Aug 1;125(8):525-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2011.03.003

- Garg S, Pande S. Learning to Sustain Change: Mitanin Community Health Workers Promote Public Accountability in India. Accountability Note. 2018 Aug(4). [Cited 2022 Sep 21]. Available from: https://accountabilityresearch.org/publication/learning-to-sustain-change-mitanin-community-health-workers-promote-public-accountability-in-india/

- Baghel A, Jain KK, Pandey S, Soni GP, Patel A. Factors influencing the work performance of Mitanins (ASHA) in Bilaspur district, Chhattisgarh, India: a cross-sectional study. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017 May;5(5):1921-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20171818

- Guha I, Raut AV, Maliye CH, Mehendale AM, Garg BS. Qualitative Assessment of Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) Regarding their roles and responsibilities and factors influencing their performance in selected villages of Wardha. Int J Adv Med Health Res. 2018 Jan 1;5(1):21. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJAMR.IJAMR_55_17

- Teela KC, Mullany LC, Lee CI, Poh E, Paw P, Masenior N, et al. Community-based delivery of maternal care in conflict-affected areas of eastern Burma: perspectives from lay maternal health workers. Soc Sci Med. 2009 Apr;68(7):1332-40. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.033. Epub 2009 Feb 18. PMID: 19232808.

- Hadi A. Management of acute respiratory infections by community health volunteers: experience of Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC). Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(3):183-9. Epub 2003 May 16. PMID: 12764514.

- Gazi R, Mercer A, Khatun J, Islam Z. Effectiveness of depot-holders introduced in urban areas: evidence from a pilot in Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2005 Dec;23(4):377-87. PMID: 16599109.

- Torpey KE, Kabaso ME, Mutale LN, Kamanga MK, Mwango AJ, Simpungwe J, et al. Adherence support workers: a way to address human resource constraints in antiretroviral treatment programs in the public health setting in Zambia. PLoS One. 2008 May 21;3(5):e2204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002204. PMID: 18493615.

- Saprii L, Richards E, Kokho P, Theobald S. Community health workers in rural India: analysing the opportunities and challenges Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) face in realising their multiple roles. Human Resour Health. 2015 Dec;13(1):1-3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-015-0094-3

- Nyonator FK, Awoonor-Williams JK, Phillips JF, Jones TC, Miller RA. The Ghana community-based health planning and services initiative for scaling up service delivery innovation. Health Policy Plan. 2005 Jan;20(1):25-34. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi003. PMID: 15689427.

- Lusambili AM, Nyanja N, Chabeda SV, Temmerman M, Nyaga L, Obure J, et al. Community health volunteers challenges and preferred income generating activities for sustainability: a qualitative case study of rural Kilifi, Kenya. BMC Health Services Res. 2021 Dec;21(1):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06693-w

- Nikkhah HA, Redzuan MR. The role of NGOs in promoting empowerment for sustainable community development. J Human Ecol. 2010 May 1;30(2):85-92. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2010.11906276

- Colvin CJ, Hodgins S, Perry HB. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 8. Incentives and remuneration. Health Res Policy Systems. 2021 Oct;19(3):1-25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00750-w

- Daniels K, Odendaal WA, Nkonki L, Hongoro C, Colvin CJ, Lewin S. Incentives for lay health workers to improve recruitment, retention in service and performance. The Cochrane Library. 2014;7. https://doi.org/10.1002%2F14651858.CD011201.pub2

- Kok MC, Kane SS, Tulloch O, Ormel H, Theobald S, Dieleman M, et al. How does context influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? Evidence from the literature. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-015-0001-3