LAW

COMMENT: Reproductive rights of women with intellectual disability in India.

Sundarnag Ganjekar, Sydney Moirangthem, Channaveerachari Naveen Kumar, Geetha Desai, Suresh Bada Math

Published online first on July 12, 2022. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2022.050Abstract

The reproductive rights of women with intellectual disability (WID) are a matter of concern for all stakeholders, including the woman herself, caregivers, guardians and her treating physicians. The judicial system often calls upon psychiatrists to opine regarding the “capacity to consent” of a WID to procedures such as medical termination of pregnancy and permanent sterilisation. Apart from physical and obstetric examinations, assessment of mental status and intelligence quotient (IQ) are also carried out to facilitate an understanding of the above issue. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, (RPwD) and the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017, elucidate what constitutes free and informed consent as well as how to assess capacity. The assessment process of “capacity to consent” to reproductive system procedures among WID is important and can guide clinicians. Before assessing capacity, the treating physicians should educate a WID with appropriate information on the proposed procedure, its risks and benefits through various means of communication and then evaluate the “capacity to consent” to the procedure. This article summarises the provisions of the existing legislations on the reproductive rights of WID and puts forward guidance for clinicians on how to approach the issue.

Keywords: women with intellectual disability, informed consent, capacity assessment, reproductive rights, pregnancy, medical termination of pregnancy, menstrual hygiene

Introduction

In India, women with intellectual disability (WID) face dual challenges — that of being a woman in a patriarchal society and the intellectual disability itself. Intellectual disability, by definition, is a condition characterised by significant limitations both in intellectual functioning (reasoning, learning, problem-solving) and in adaptive behaviour, which covers a range of everyday, social and practical skills [1]. WID are often perceived as women devoid of identity, femininity, sexuality, and companionship and are deprived of opportunities for motherhood [2]. The challenges and dilemmas encountered by them and their caregivers1 arise in the contexts of: training for menstrual hygiene [3], sex education [4], marriage and procreation [5], contraception and pregnancy planning, antenatal care, consent for caesarean delivery [6], breastfeeding advice [7], role and responsibilities of a mother [8], safety of the child [9], and permanent sterilisation [5]. The above challenges often pose barriers to planning rehabilitation for the best possible quality of life for WID.

The laws relevant to the reproductive rights of WID

It is essential to understand the existing legislation in India that talks about women’s reproductive rights, and to know whether these legislations mention the reproductive rights of WID.

The Indian ConstitutionArticle 21 of the Indian Constitution [10], the Right to Life and Liberty, it is the right of a woman to make a reproductive choice, and it is a dimension of her “personal liberty”. Women can choose to procreate or abstain from procreation. The reproductive rights of women with intellectual disabilities have been discussed on several occasions [11], and each time the Supreme Court of India has upheld their “personal liberty” [12, 13].

The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) marked a paradigm shift in attitudes and approaches to persons with disabilities on December 13, 2006 [14]. Persons with disabilities are no longer considered objects of charity, medical treatment, and social protection but rather as subjects with rights and choices as to how they want to live and what treatments, if any, they wish to use. India signed and ratified the same on October 01, 2007. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 (RPwD Act) [15] replaced the earlier Persons with Disability (PwD) Act 1995, and was intended to incorporate this paradigm shift. It defines persons with disability (PwD) as any person with long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments which, in interaction with barriers, hinder full and effective and equal participation with others.

The other Indian laws which do impact the reproductive rights of women include the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act (MTP Act), 1971 [16], its Amendment of 2020 (MTP Amendment Act) [17], the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 (MHCA) [18], the National Trust for the Welfare of Persons with Autism, Cerebral Palsy, Mental Retardation and Multiple Disabilities Act 1999 (NT Act ) [19], the National Commission for Women Act, 1990 (NCW Act) [20], the Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 [21, 22], and the Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) Regulations 2002 [23]. However, not all these Acts recognise the reproductive rights of WID, and this is dealt with in detail in Table 1.

Reproductive rights and challenges among WID

Among PwD, women are probably the most vulnerable population. Among them, WID have been reported to be at risk for sexual abuse and human rights violations both at home and in shelters [24, 25]. Furthermore, guardians2 and caregivers of a WID face a dilemma about procreation and motherhood rights, irrespective of whether she is in a state-run special home or staying with her parents [8]. In addition, there have been instances where WID were forced to undergo a hysterectomy to avoid menstruation in the state-run shelter homes [26].

Menstruation and its care are another perceived challenge for caregivers and guardians. The reproductive hormones play a role in menstruation, development of secondary sexual characteristics, and libido in WID, as they do for women in general. WID may face difficulties understanding and interpreting the physiological changes and may be at risk for sexual exploitation and unwanted, unplanned pregnancies. Caregivers and guardians often find it challenging to train them in menstrual hygiene, especially those with moderate to profound intellectual disability. In many instances, parents might seek hysterectomy to protect WID. Procedures like these often violate their reproductive rights, autonomy, and right to life [5]. Unplanned/unwanted pregnancy and its medical termination are additional challenges.

The questions that arise in these contexts are: Can a WID provide informed consent? Can she consent to bear and rear a child? Can she consent to terminate the pregnancy or opt for temporary or permanent sterilisation? We discuss below the reproductive rights of WID using a case scenario.

Case scenario

A 26-year-old WID is brought to the obstetrician by her parents for medical termination of her pregnancy (MTP). On examination, the woman is found to be 19 weeks pregnant with possible low intelligence, and she is unaware of her pregnancy status. The obstetrician seeks a psychiatrist’s opinion regarding her ability to consent to the MTP. A detailed assessment by the psychiatrist reveals that she has a moderate intellectual disability. She needs assistance in her activities of daily life. On enquiring about her pregnancy, she reports that she likes babies and can play with them. She is unable to reveal details about the father of the baby. She expresses happiness after being told she is pregnant. However, she cannot comprehend the roles and responsibilities of being a mother. The parents state that they want her to undergo a hysterectomy and MTP as it is difficult for them to provide care during pregnancy and protect their daughter from unwanted future pregnancies. She has a poor understanding of self-care, menstruation, and sexual knowledge.

Challenges arising in the case

In the above clinical context, the challenges that arise are:

- 1. How to assess the “capacity” to give informed consent for termination of the pregnancy and or temporary/permanent sterilisation in an adult WID?

- 2. Who will be responsible for the care of her baby if the mother is unable to look after the baby?

- 3. Can caregivers or guardians consent to termination of a WID’s pregnancy and/or permanent/temporary sterilisation?

- 4. What are the role and responsibilities of the psychiatrist in this scenario?

In Table 1, we summarise the relevant Acts, rules and regulations governing the reproductive rights of WID in India.

Table 1: The current Indian Acts, Rules and Regulations concerned with reproductive rights of WIDActs / Rules / Regulation |

Relevant sections |

Provisions within the Act / Rules / Regulation |

| The Constitution of India [10] | Section 21 | No person shall be deprived of his/her life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law. |

| The Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPwD 2016) [15] | Section 10 | (1) The appropriate Government shall ensure that persons with disabilities have access to appropriate information regarding reproductive and family planning. (2) No person with disability shall be subject to any medical procedure which leads to infertility without his or her free and informed consent. |

| Section 13 | (2) The appropriate Government shall ensure that the persons with disabilities enjoy legal capacity on an equal basis with others in all aspects of life and have the right to equal recognition everywhere as any other person before the law. | |

| Section 13 | (5) Any person providing support to the person with disability shall not exercise undue influence and shall respect his or her autonomy, dignity and privacy | |

| Section 14 | Provision for guardianship: a district court or any designated authority, as notified by the State Government, finds that a person with disability, who had been provided adequate and appropriate support but is unable to take legally binding decisions, maybe provided further support of a limited guardian to take legally binding decisions on his behalf in consultation with such person, in such manner, as may be prescribed by the State Government. | |

| Section 92 | (f) whoever performs, conducts or directs any medical procedure to be performed on a woman with a disability which leads to or is likely to lead to termination of pregnancy without her express consent except in cases where the medical procedure for termination of pregnancy is done in severe cases of disability and with the opinion of a registered medical practitioner and also with the consent of the guardian of the woman with disability, shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than six months, but which may extend to five years and with fine. | |

| The Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, 1971[16], Amendment 2020 [17] | Section 3 | Abortion is allowed if continuation of the pregnancy could involve a risk to the life of the pregnant woman or cause grave injury to her physical or mental health, or there is a substantial risk that if the child were born, it would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped. |

| Section 3 | 4 (a) No pregnancy of a woman, who has not attained the age of eighteen years, or, who, having attained the age of eighteen years, is a [mentally ill person], shall be terminated except with the consent in writing of her guardian. | |

| The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 (MHCA) [18] | Section 20 | (h) to have adequate provision for wholesome food, sanitation, space and access to articles of personal hygiene, in particular, women’s personal hygiene be adequately addressed by providing access to items that may be required during menstruation; |

| Section 95 Prohibited procedures | (c) sterilisation of women when such sterilisation is intended as a treatment for mental illness. | |

| The National Trust for the Welfare of Persons with Autism, Cerebral Palsy, Mental Retardation and Multiple Disabilities Act, 1999 [19] | Reproductive rights of WID are not adequately addressed Section 14: Appointment of guardianship Section 15: Duties of guardian Section 17: Removal of guardian |

|

| Women’s Commission Act, 1990 [20] | Reproductive rights of WID are not adequately addressed | |

| The Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993 and The Protection of Human Rights (Amendment) Act 2019 [21, 22] | Reproductive rights of WID are not adequately addressed | |

| The Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) 2002 [23] | Chapter 1, Point No. 1.9, Evasion of Legal Restrictions: The physician shall observe the laws of the country in regulating the practice of medicine and shall also not assist others to evade such laws. He should be cooperative in observance and enforcement of laws and regulations in the interest of public health. A physician should observe the provisions of the Mental Health Care Act, 2017; Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities and Full Participation) Act, 1995, such other Acts, Rules, Regulations made by the Central/State Governments or local Administrative Bodies or any other relevant Act relating to the protection and promotion of public health. Chapter 6, Point 6.6, Human Rights: The physician shall not aid or abet torture, nor shall he be a party to either infliction of mental or physical trauma or concealment of torture inflicted by some other person or agency in clear violation of human rights. |

It is clear from Sections 10, 13 and 92 of the RPwD Act, 2016 (See Table 1), that to be a mother is the personal right of a woman, and no one can curtail that right unless it is deemed to pose a threat of grave injury to the physical or mental health of the woman. The Constitution of India guarantees the right to “personal liberty” and the laws enacted under its provisions do not support termination of pregnancy for a WID. In a landmark Supreme Court judgment regarding termination of pregnancy in a woman with intellectual disability [12, 13], the apex court observed that persons with borderline, mild or moderate intellectual disability are capable of being good parents. The judgment had also said that there is a possibility that a woman with a low IQ can possess social and emotional capacities that enable her to be a good mother. Further, the apex court stated that it could not order a termination without the consent of an adult WID [12]. The above case and the Supreme Court’s judgment provide an example of the protection of reproductive rights of WID under the law. Section 14 of the RPwD Act, and of the National Trust Act state that persons with disability who are unable to take legally binding decisions, may be provided the support of a “limited guardian” to take such decisions on their behalf. This is discussed in detail later.

However, it is also evident that no legislation addresses the guardian’s role in consent, capacity and implementation of rights of WID, which is a significant lacuna in Indian jurisprudence.

Approach to “capacity to consent”“Capacity to consent” can be equated with the subjective standard of informed consent. It means that the individual who has the “capacity to consent” has both “legal capacity” and “mental capacity” to consent. The UNCRPD Committee on the rights of persons with disabilities, in its general Comments No 1 (2004), interpreted Article 12 and provided guidance on how legal capacity applies to persons with intellectual disability, highlighting that “legal capacity” and “mental capacity” are not the same. “Legal capacity is the ability to hold rights and duties (legal standing) and to exercise those rights and duties (legal agency)”. “Mental capacity”, on the other hand, is a contested concept that has to do with the ability to make decisions. It is contested partly on account of different notions about when one can say a person can decide [27]. Assessment of the “capacity to consent” can be done through the status approach (focusing on the impairment), the outcome approach (focusing on consequences) or the functional approach (focusing on actual decision-making skills). It is a challenging task for mental health professionals to take the functional approach for assessing the mental capacity of WID to give consent for termination of pregnancy and/or temporary/permanent sterilisation. From an outcome approach, it is challenging to know, in a woman with moderate to severe intellectual disability, how much she understands about the medical procedure and its consequences; whether she can weigh the risks and benefits of the proposed procedure; if she can understand whether or not the proposed procedure is reversible.

IQ level (status approach) might indirectly reflect the capacity of WID to make a reasonable decision regarding the procedure. “Capacity to consent” revolves around four important concepts: (i) comprehension, (ii) retention of the information, (iii) weighing the risks and benefits of the purported procedure and (iv) communication of choice. However, the RPwD Act is silent on the issue of “capacity to consent”. Hence, it is reasonable to borrow the concept of “capacity” under Section 4 of the MHCA. Once the capacity is assessed, the psychiatrist has to assess whether it is a case of complete capacity to consent, limited capacity to consent, or absence of capacity to consent.

The RPwD Act, 2016, clearly states, in Section 10(2), that “No person with disability shall be subject to any medical procedure which leads to infertility without his or her free and informed consent”. However, the Act does not define informed consent. On the other hand, the MHCA, 2017, defines informed consent as “consent given for a specific intervention, without any force, undue influence, fraud, threat, mistake or misrepresentation, and is obtained after disclosing to a person adequate information including risks and benefits of, and alternatives to, the specific intervention in a language and manner understood by the person”. Although this definition refers to a person with “mental illness”, it might be used for a WID in a specific situation because informed consent is both an ethical and legal need for medical practitioners.

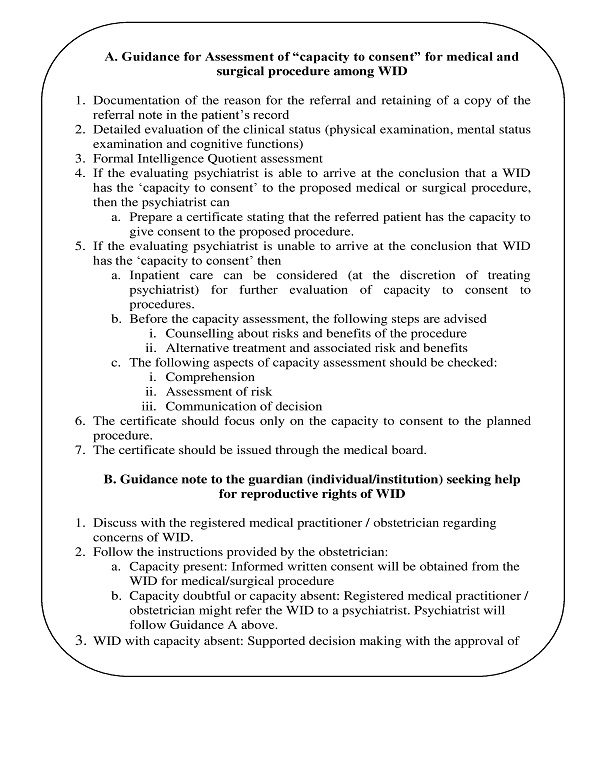

Box 1 shows the workflow of steps required to demonstrate the “capacity to consent” to medical/surgical procedures among WID.

The assessment of “capacity to consent” to a medical/surgical procedure could result in a finding of — i) capacity present, ii) capacity doubtful, or iii) capacity absent.

- Capacity present

If capacity is present, the choice of the WID will prevail. The informed consent obtained will be valid under the law

- Capacity doubtful

In a real-life scenario, psychiatrists often find themselves in a dilemma about the presence or absence of capacity despite thorough evaluation. In such a scenario, the psychiatrist should engage with and empower the WID through training to achieve the required level of capacity. This can be done by providing appropriate information, education and communication using materials such as pictures, videos, mannequins. Other methods include role-play, vicarious learning, virtual aids and provision of other relevant material. This could help them achieve the desired level of capacity to consent. It is recommended that the capacity be reassessed after the above training has been completed, which may take a few weeks. However, this may not be feasible in all cases where the pregnancy is advanced, and the timeline available for making a decision regarding termination under the provisions of the MTP (Amendment) Act of 2020 is short.

- Capacity absent

In the absence of capacity to consent to medical procedures such as MTP or permanent / temporary sterilisation, the clinician can consult the rules and regulations under the RPwD Act, 2016. The Act has a provision in Sec 14(1) for a “limited guardian” to take legally binding decisions in consultation with the WID, in the absence of capacity. “Limited guardianship” means “a system of joint decision-making which operates on mutual understanding and trust between the guardian and the person with disability, which shall be limited to a specific period, and for a specific decision and situation and shall operate in accordance to the will of the person with disability.” The Act also states that every caregiver or guardian appointed for a person with disability can function as a limited guardian.

The logical reasoning capacity of the individual can be evaluated through intellectual quotient (IQ) assessment. The IQ is not the sole measure to assess capacity for providing informed consent. However, the capacity to give consent is inversely related to the severity of the intellectual disability. Moreover, informed consent is a process and should be facilitated using all possible means of communication to the WID. Table 2 shows the minimum documentation required for the “capacity to consent” to medical procedures among WID.

Table 2: Minimum documentation required for the “capacity to consent” for the medical procedures among WID| Procedure | Documentation required |

| Clinical examination | Complete physical examination; Mental status examination |

| Assessments | Intelligence quotient (IQ); Capacity assessment as per MHCA 2017 |

| Information about medical procedure provided to the WID | 1. Nature of procedure 2. Risk and benefit of procedure 3. Reasonable alternatives 4. Risk and benefits of alternatives |

| Patient’s understanding on medical procedure | Clinical assessment on the patient’s understanding of elements 1 through 4 |

There is no established cut off IQ value below which an individual can be deemed to have no capacity. A woman with moderate to severe intellectual disability may express her wish, but her actual capacity (eg for the physical care of the infant) might be insufficient. The value of an IQ does not give per se an understanding of whether the mother can bear and rear the child. Moreover, it may not be possible for women with intellectual disability of a severe and profound degree to be empowered to make complex decisions such as consent for medical and surgical procedures.

If the capacity to consent is absent, Section 14, RPwD Act, 2016, describes the provision of guardianship, limited/total guardianship to take legally binding decisions. In this scenario, the responsibility of guardianship assigned under the Act by the District Court will enable the WID’s guardians to take appropriate decisions regarding the WID.

Legal capacity of WID relating to her reproductive rightsIn cases where “mental capacity” is considered “absent” or “doubtful”, ie where no improvement is be expected, supported decision making regarding the woman’s reproductive rights may be necessary. The law provides for termination of a pregnancy in a WID with loss of capacity, supported by the opinion of a registered medical practitioner and with the consent of a caregiver or guardian of the woman with disability (Sec 92, RPwD Act). However, even where mental capacity is impaired, legal capacity inheres. That means the WID will have the legal capacity, and therefore, an unqualified right to hold and exercise the right to make decisions. Any substituted decision-making, however limited, is incompatible with Article 12 of the UNCRPD.

Role and responsibilities of psychiatristsThe role of a psychiatrist is to certify the mental health status, intellectual ability and “capacity to consent” of a WID to any medical procedure. Certification of the severity of intellectual disability (as measured through Intelligence Quotient) is a measure of impairment, focusing on the status approach. However, whether the numerical value of IQ enables or limits the WID from taking certain important decisions merits a different discussion. The issue of decision-making becomes pertinent in challenging situations such as medical termination of pregnancy, tubectomy, oophorectomy, hysterectomy and contraception, which might be against the constitutional rights of the women. It is crucial for psychiatrists to understand that Article 12 of UNCRPD guarantees a person with disabilities equal recognition under the law. It reaffirms that persons with disabilities have legal capacity, and therefore, an unqualified right to hold and exercise the right to make decisions.

Handling certain bioethical and legal dilemmas around the reproductive rights of WID

The process of supporting the right to reproduction among WID also includes providing appropriate consent for caesarean delivery if indicated, training in breastfeeding the infant and roles and responsibilities as a new mother.

Consent for caesarean deliveryWith the best interest of a healthy infant in mind, an obstetrician might suggest caesarean delivery for a pregnant WID. However, by law, obstetricians are not bound to seek judiciary approval for WID to undergo caesarean delivery. At the same time, obstetricians will not be held legally responsible for not seeking a court order when a WID, having adequate capacity, has knowingly refused a caesarean delivery. Nevertheless, there could be certain situations where obstetricians might consider actively challenging a WID with her absent or total capacity to consent. For instance, (i) the unborn baby could suffer irrevocable harm without a caesarean delivery, (ii) a caesarean delivery is clearly indicated and likely to be effective, and (iii) the risk associated with a caesarean delivery to the health of the pregnant WID is low [28]. In an emergency situation, it would be prudent for the treating obstetrician to consider taking a second opinion from a colleague or from a medical board.

Breastfeeding advice for WIDFollowing the delivery, a WID might face challenges with respect to breastfeeding her new-born. The prenatal/antenatal period is a critical period for infant feeding education and information to pregnant WID. This may include familiarising the pregnant WID with breastfeeding benefits, possible challenges and advice on seeking of support [29]. The caregiver or guardian plays a significant role in prenatal/antenatal education as well as post-delivery support for a WID.

Roles and responsibilities of WID as a motherInadequate knowledge about basic childcare, inconsistent mother-child interactions could be present in a WID. She might find it challenging to provide an age-appropriate stimulating environment to the child. Her difficulties in decision-making and problem-solving skills might impair her abilities to handle complex tasks of baby care leading to feelings of frustration and rejection of the baby. The prenatal/antenatal period would be the right time to educate the mother regarding infant care. Post-delivery interventions should first focus on simpler activities with the baby, such as play when the baby is not crying, changing clothes and infant massage, using verbal commands, pictures, videos or “pretend baby” for the practice of skills. A positive reinforcement, even for small gains made, could be encouraging for mothers with intellectual disability. She might also require training in how to avoid danger, how to soothe the infant, and how to get help in handling a crying baby [30]. The caregivers or guardians can help her through guided practice.

Safety of the childImpaired decision-making and problem-solving skills among WID might pose a challenge to the child’s safety. The caregiver’s or guardian’s support is of great importance for the safety of the child. It might be possible to train the WID using audio-visual and print materials to convey advice to ensure the health and safety of the child. The legal basis of the safety of the child cared for by a mother with intellectual disability needs detailed evaluation, with direct and indirect observation by trained professionals over a period of time.

Grounds for sterilisation proceduresIt is essential for women to maintain menstrual hygiene to prevent infections. It might be possible to train WIDs in menstrual hygiene. However, those with intellectual disability of a profound, severe, or even moderate degree might find it difficult to comprehend the training or might need repeated instruction and support. However, this cannot be a ground for hysterectomy. Further, it must be emphasised that there are no psychiatric indications for hysterectomy among WID. Neither are the apprehensions of caregivers that a WID may conceive, or be subjected to sexual abuse, or be involved in sexual activities adequate grounds for either permanent or temporary sterilisation [5].

Collective rights and their relevance to WIDCollective Rights is a concept whereby special legislations are formulated for people who can be categorised as a “class” or “type”. It draws from the interpretation of Article 14 of the Constitution of India whereby it was decided that one should not treat the unequal equally, since those with physical or mental disabilities can be considered as a class/type; laws have been made granting them certain rights specifically suited to their needs [31].

The WID may be residing in a community where people of the community support her for basic needs such as food, shelter and clothes. However, if such a woman is found to be pregnant then people of the community might not support her and insist on her undergoing termination of pregnancy. In such cases, a collective or group right comes into the picture.

A collective or group right is a right held by a group, rather than by its members individually. Collective rights guarantee the development and preservation of underprivileged groups’ and ethnic minorities’ cultural identities and forms of organisation. Article 169 of the International Labour Organization Convention recognises these rights. Collective rights can be legal or moral or both [32, 33]. The reality in India is that collective rights (family) tend to prevail over individual rights, especially in matters pertaining to reproduction for WID. This is because the state does not take much responsibility with regard to economic, social and cultural rights of WID. Hence, most of the decisions regarding reproductive rights of WID, such as termination of pregnancy and sterilisation, are taken by the family, caregivers or guardians. The parameters of collective rights with respect to the person with intellectual disability are not clear in Indian legislation. Hence, it is the duty of healthcare professionals to follow the existing provisions under the law in the best interests of WID rather than being influenced by their caregivers or guardians.

Conclusion

Under the Indian constitution, every woman has reproductive rights including whether to choose or refrain from procreation, irrespective of her intellectual capacity. Psychiatrists giving their expert opinions regarding women’s capacity to undergo temporary or permanent sterilisation or termination of pregnancy should be aware of all these relevant Indian laws. In the absence of clear provisions relating to WID, it is most important for the treating psychiatrist to be aware of the major judgments pronounced by the Supreme Court of India. It is pertinent for mental health professionals to consider other aspects of motherhood such as infant care, breastfeeding, child safety during their assessments. Rather than being prejudiced by their perceptions of the WID or by their guardians, it is important to go through the prevailing rules, regulations and provisions provided in the Indian legal system to safeguard their clinical practice and uphold the reproductive rights of WID.

Notes:1Caregiver: A caregiver is anyone who cares, unpaid, for a friend or family member who due to illness, disability, a mental health problem, or an addiction cannot cope without their support [34].

2Guardian: A guardian is a person who is appointed (by the court or under section 14 of the National Trust Act, the Local Level Committee headed by the District Collector) to look after another person or his property. He or she assumes the care and protection of the person for whom he/she is appointed the guardian. The guardian takes all legal decisions on behalf of the person and the property of the ward [35].

Conflict of Interest and funding: None declared.

Statement of similar work: None.

References

- Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Dept of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities (Divyangjan). Guidelines for Assessment of Disabilities 2018. New Delhi; MSJE; 2016 Jan 5 [Cited 2020 Feb 9]. p. 1–117. Available from: http://www.egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2018/181788.pdf

- Scotch R. Book Review: Women and Disability: The Double Handicap. Deegan MJ, Brooks NA, editors. Social Forces. 1986 Sep; [Cited 2020 Feb 9]. 65(1): 277-8. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/65/1/277/2231955

- Thapa P, Sivakami M. Lost in transition: Menstrual experiences of intellectually disabled school-going adolescents in Delhi, India. Waterlines. 2017 Oct 1;pp. 317–38.

- TARSHI Working Paper. Sexuality and Disability in the Indian Context. New Delhi; 2010[Cited 2020 Feb 9] Available from: https://www.academia.edu/36263436/SEXUALITY_AND_DISABILITY

- Roy AA, Roy AA, Roy M. The human rights of women with intellectual disability. J R Soc Med. 2012 Sep;105(9):384–9. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2012.110303

- Darney BG, Biel FM, Quigley BP, Caughey AB, Horner-Johnson W. Primary Cesarean Delivery Patterns among Women with Physical, Sensory, or Intellectual Disabilities. Women’s Health Issues. 2017 May 1 [Cited 2021 Jun 16];27(3):336–44. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5435518/

- Bakken TL, Sageng H. Mental Health Nursing of Adults With Intellectual Disabilities and Mental Illness: A Review of Empirical Studies 1994-2013. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2016 Apr 1 [Cited 2021 Jun 16];30(2):286–91. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26992884/

- Women with Disabilities India Network (WWDIN). 2014. Women with Disabilities in India (Special Chapter 1a) in: National Alliance of Women India’s India 4th and 5th NGO Alternative Report on CEDAW. Pgs 185-198. http://kalpanakannabiran.com/pdf/CEDAW-BOOK2014.pdf

- Coren E, Ramsbotham K, Gschwandtner M. Parent training interventions for parents with intellectual disability. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Jul 13 [cited 2021 Jun 16]; 7(7). CD007987. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007987.pub3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6513025/

- Ministry of Law and Justice. The Constitution of India. New Delhi: MOLJ;2019 pp. 1–281.

- Chandra A, Satish M, and Center for Reproductive Rights. Securing Reproductive Justice in India A Case Book. New Delhi: Center for Reproductive Rights and Center for Consititutional Law, Policy and Governance , National Law University; 2019 Dec 20.

- Supreme Court of India. Suchita Srivastava & Anr vs Chandigarh Administration. p. 1–15. Civil Appeal No.5845 of 2009 [Cited 2021 Apr 29]. Available from: http://indiankanoon.org/doc/1500783/

- Supreme Court of India. Ms. Z vs The State of Bihar and Others. p.1-60. Civil Appeal No. 10463 of 2017[Cited 2021 Apr 29]. Available from: https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2017/14156/14156_2017_Judgement_17-Aug-2017.pdf

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – Articles New York: UN; 2006 Dec 13 [Cited 2020 Apr 29]. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html#Fulltext

- Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Govt of India. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016. New Delhi: MoSJE;2017 Apr [Cited 2020 Apr 29]. Available from: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2155?sam_handle=123456789/1362

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt of India. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act 1971.[Cited 2020 Jun 29]. Available from: https://main.mohfw.gov.in/acts-rules-and-standards-health-sector/acts/mtp-act-1971

- Ministry of Law and Justice, Govt of India. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy (Amendment) Act, 2021. New Delhi: MOSJ.2021 Mar 25[Cited 2021 Apr 29]. Pp. 1–6.

- Ministry of Law and Justice, Govt of India. The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017. New Delhi: MOLJ; 2017 Feb 7 [Cited 2021 Apr 29]. p. 1–51.Available from: https://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2017/175248.pdf

- Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Govt of India. The National Trust for Welfare of Persons with Autism, Cerebral Palsy, Mental Retardation and Multiple Disabilities Act, 1999. New Delhi:MOSJE; 1990 Dec 30 [Cited 2021 Apr 29]. Available from: https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A1999-44_0.pdf

- Ministry of Law and Justice, Govt of India. The National Commission for Women Act, 1990. New Delhi: Ministry of Law and Justice; 1990 Aug 30 [Cited 2021 Apr 29]. Available from: https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/ncwact.pdf

- Ministry of Law and Justice, Govt of India. The Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993. New Delhi:MOLJ; 1993 Sep 28 [Cited 2021 Apr 29]. Available from: https://nhrc.nic.in/acts-&-rules/protection-human-rights-act-1993

- Ministry of Law and Justice, Govt of India. The Protection of Human Rights (Amendment) Act, 2019. NewDelhi: MOLJ; 2019 Jul 27 [Cited 2021 Apr 29]. Available from: https://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2019/208592.pdf

- Medical Council of India. The Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) Regulations. 2002 Apr 6 [Cited 2021 Apr 29]. Available from: https://wbconsumers.gov.in/writereaddata/ACT%20&%20RULES/Relevant%20Act%20&%20Rules/Code%20of%20Medical%20Ethics%20Regulations.pdf

- Poreddi V, Ramachandra, Math S, Thimmaiah R. Human rights violations among economically disadvantaged women with mental illness: An Indian perspective. Indian J Psychiatry 2015 Apr 1 [Cited 2020 Feb 18];57(2):174. Available from: http://www.indianjpsychiatry.org/text.asp?2015/57/2/174/158182

- National Commission for Women. Review of Psychiatric Homes/Mental Hospitals of Government Sector in India with Special reference to the female patients in IPD. New Delhi:NCW; 2019.

- Márquez-González H, Valdez-Martinez E, Bedolla M. Hysterectomy for the Management of Menstrual Hygiene in Women With Intellectual Disability. A Systematic Review Focusing on Standards and Ethical Considerations for Developing Countries. Front Public Heal. 2018 Nov 28 [Cited 2020 Jun 29];6:338. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00338/full

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Committee. General Comments 1. 2004 [Cited 2022 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf

- Deshpande NA, Oxford CM. Management of pregnant patients who refuse medically indicated cesarean delivery. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2012 [Cited 2021 Jun 16];5(3–4):e144-50. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23483714/

- Guay A, Aunos M, Collin-Vézina D. Mothering with an Intellectual Disability: A Phenomenological Exploration of Making Infant-Feeding Decisions. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2017 May 1 [Cited 2021 Jun 16];30(3):511–20. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27878910/

- Chandra PS, Ragesh G, Kishore T, Ganjekar S, Sutar R, Desai G. Breaking Stereotypes: Helping Mothers with Intellectual Disability to Care for Their Infants. J Psychosoc Rehabil Ment Health. 2017;1-6.

- Sathe SP, Narayana S, eds. Liberty, Equaltiy and Justice: Struggles for a New Social Order. ILS Law College, Platinum Jubliee Commemoration Volume. Eastern Book Company 2003, Reprinted 2021.

- Friends of the Earth International. Collective rights. [Cited 2021 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.foei.org/what-we-do/collective-rights

- Group Rights. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Archive, Summer 2016 Edition. [Cited 2021 Sep 2]. Available from: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2016/entries/rights-group/

- Angothu H, Chaturvedi SK. Civic and legal advances in the rights of caregivers for persons with severe mental illness related disability. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2016 [Cited 2021 Aug 28];32(1):28. Available from: https://www.indjsp.org/article.asp?issn=0971-9962;year=2016;volume=32;issue=1;spage=28;epage=34;aulast=Angothu

- The National Trust, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. Guardianship. Updated 2022 Jan 4 [Cited 2021 Aug 28]. Available from: https://thenationaltrust.gov.in/content/innerpage/guardianship.php