REFLECTIONS

Remembering Zafrullah Chowdhury (1941-2023): Reflections on his second death anniversary

S Srinivasan

Published online first on April 11, 2025. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2025.027Abstract

The cost of healthcare became an intense political issue with the systematic analysis of multinational pharmaceutical corporations and their track record. Medicines and their cost, and affordable access to healthcare, were too important to be left to doctors in big hospitals and executives of drug companies, and to indifferent governments. Such issues were discussed through the 1970s to the turn of the 21st century. Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury was part of this generation of pioneers. On his second death anniversary, the author remembers his qualities as a person and as a freedom fighter, and his contributions to public health, especially the landmark 1982 Drug Policy of Bangladesh.

Keywords: Zafrullah, Bangladesh Drug Policy, freedom movement, courage, visionary

That health costs money and is also a political issue — was a realisation that dawned late among health professionals, maybe in the 1970s. It became an intense political issue when multinational pharma corporations and their track record started being analysed systematically. Should medicines cost ‘so much’? Should access to healthcare cost ‘so much’? Medicines and their cost, healthcare and its affordable access were too important to be left to doctors in big hospitals and big executives of big pharma companies, and to indifferent governments. There was intense discussion of these issues right through the ‘70s to the turn of the 21st century. Ideas like village health workers, bare foot doctors, were looked at as ways of enhancing availability and accessibility. Zafrullah was part of this generation of pioneers of the 1970s and onwards.

Zafrullah Chowdhury (Zafarbhai hereafter) was a patriot in the best and widest sense of the term. He loved people, poor people of all countries, and made it clear that he supported all causes that helped the poor, whenever there was a dilemma about which path to take.

Like most young Bangladeshis, he cut his teeth during the run-up to the birth of Bangladesh. “Our Bangalis are different from your Bangalis,” he told me in one of those long, wide-ranging late-night conversations with him. I asked why. He replied, “We have handled guns and fought for freedom.”

Bangladeshis were not given a choice between violence and non-violence during the War of Liberation (Swadhinata Juddho) in 1971. Zafarbhai’s major contribution during the 1971 War of Liberation was the setting up of the Bangladesh Field Hospital — along with Khaled Mosharraff, a childhood friend. When the Liberation War broke, Zafarbhai was completing his training as a general, orthopaedic and vascular surgeon in the UK, gaining a Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS) in the process. He was driving a Citroen car at that time, and in his words “blissfully unaware of poverty and health care issues”. He was a part of the Bangla freedom fighters’ group in the UK ― lobbying for an Independent East Bengal, based in London — but soon realised that the appropriate theatre of action was not London but the land soon to be called Bangladesh, and parts of Tripura and elsewhere in India, where he set up the field hospital.

The 480-bed field hospital at the site of the Liberation War catered to refugees and wounded freedom fighters. I once asked him why Bangladesh ignores the Independence celebrations of India and Pakistan of circa 1947. And rather celebrates March 26, 1971, as Independence Day. He said 1947 was merely a change of masters.

The field hospital also opened Zafarbhai’s eyes to the possibility and feasibility of involving and training poor women in healthcare, when nothing like “standard” care was available. After the war, that led him to train rural women to conduct deliveries in hospitals and primary health centres. The Bangladesh equivalent of Indian Medical Council accused him of violating the law by employing paramedics/village health workers in obstetric and gynaecological procedures. His reply to the Medical Council was “You get your finest MBBS graduates and ask them to do tubectomy and compare with our women paramedics who haven’t gone past Class 10.”

They did. The women paramedics passed with flying colours in comparison to the young formal medical degree holders who stuttered and panicked.

The Bangladesh medical authorities, however, would not let him get away with his dream of an alternative medical college. In this alternative medical college, fresh MBBS students were to spend the majority of their time in a poor village with the concomitant pursuit — in the first year — of courses in anthropology, sociology, gender studies, etc, instead of anatomy and physiology. The student would graduate at the end of the five years, only if the health parameters of the village that the student had been seconded to 5 years earlier, had improved. There also was a plan for special provisions for admission for experienced nurses, midwives and paramedics into the MBBS course, which also did not come to pass. What was approved was the standard medical course — students from mostly well-to-do middle-class families embracing the beaten track. The Gonoshasthaya Samaj Vittik Medical College (see https://gonosvmc.edu.bd/) nevertheless tried hard, and still does, to be different.

In everything Zafarbhai did, there was a spirit of innovation, courage and daring, and a relentless pushing of boundaries. That showed when he successfully persuaded the then President Ershad to introduce the 1982 Bangladesh Drug Policy. The Policy weeded out unscientific and irrational drugs in the country1 and introduced a simple uncomplicated formula for a ceiling price on medicines, unlike the current “simple average” formula in India. Equally important, brand names were banned.

He would constantly tell his Indian friends, when he came to India, that with the introduction of the 1982 Bangladesh Drug Policy, it was Bangladesh that implemented “your country’s Hathi Committee (1975) Recommendations” successfully. Touche!

Bangladesh used to import drugs majorly from multinational companies (MNCs) — both formulations and bulk drugs. That changed. The Drug Policy itself was a bold measure with Western pharma MNCs opposing it in every which way, even as they got their ambassadors to threaten stoppage of foreign aid to Bangladesh. Bangladesh went ahead nevertheless.

The Gonoshashtaya Pharmaceuticals Ltd set up in 1981 by Zafarbhai and team was a pioneering formulations unit making tablets, capsules, ointments, and injections at prices that were way less than comparative imported formulations.

Circa late 1980s, Zafarbhai and his teammates took one more step towards self-reliance and affordability: the making of active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) — antibiotic amoxicillin from 6-aminopenicillanic acid (6-APA) — and costing much less than Western market leaders. This was a first for Bangladesh.

The Medical College (Gonoshasthaya Samaj Vittik Medical College) was part of the Gono (People’s) University, also located in the GK (Gonoshasthya Kendra: People’s Health Centre) campus where smoking and drinking were prohibited, as well as junk food and harmful cosmetics. The security personnel at the gate were women — not men. His driver Saleha Apa was the first woman in Bangladesh to have a driving licence. She made it to the cover of the Health for All magazine. Most of his women workers and paramedics drove bicycles — again a first for Bangladesh.

The Gonoshasthya Kendra/GK (People’s Health Centre) at Savar, outside Dhaka, was an evolution from the field hospital days of Tripura. Over time, it became the nerve centre of several primary healthcare centres, across neighbouring districts, the Gono University and the medical college, and many others. GK also set up an urban hospital in Dhaka for quality urban affordable care. He said there are a lot of poor people in urban areas, and we do not focus on their healthcare. In his last few years, he suffered various problems, including kidney issues, and needed regular dialysis. He was keen on setting up low-cost dialysis care centres. If it was costly for him, it must be unaffordable for the common person. He sent some of his senior doctors to India (and probably other countries) to look into low-cost dialysis care. One of his doctors came to India and to Vadodara, where I live. He had found somebody in Vadodara, who makes erythropoietin which is a major cost component of dialysis. That was quintessential Zafarbhai — he knew more about useful things available in India than his Indian friends.

Zafarbhai had, of course, enemies and detractors within Bangladesh and outside. He often was at loggerheads with professional organisations like Bangladesh Medical Association and Bangladesh Medical Council. That was because Zafarbhai advocated policies inconvenient to the medical profession, especially those who valued profit maximisation at the expense of the health of the people. The National Health Policy, one such public policy intervention espoused by Zafarbhai, advocated a ban on private practice by experts working in medical colleges. The experts were not amused. Often his vehicles were attacked, and his paramedics were stoned (at least one of them, Jharna, died after a brick hit by local quacks); and a couple of times, the Gonoshasthaya Pharma factory too was attacked. The police were not quick to attend. But he and his colleagues fought on. Most shocking for his Indian friends was the cancellation of his Indian visa by the Government of India — because he apparently argued in a Dhaka seminar, against a cross-country highway from India to Mizoram via Bangladesh, and further eastwards. After that we never got to see him in India. It was a loss for him, but more for his Indian friends who shared his dreams of universal healthcare for all. Politics and governments can be petty and vindictive.

(Talking of his adversaries and detractors, one of his last “skirmishes”, if you will, was in November 2018 when the Bangladesh government abruptly revoked, at the last minute, its permission to conduct the People’s Health Assembly in the campus of the Gonoshasthaya Kendra — leading to a crisis for the PHA’s organisers and delegates. Ultimately, a make-do Assembly was held, at short notice, in the campus of Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee (BRAC), a well-known NGO.)

Surely, for Bangladesh to have better health indicators today than India, Zafarbhai can claim some credit. In his death, we lost a public health hero, a man of enormous integrity and courage. To the poor, Zafarbhai was an endearing father, brother, and uncle; and to friends everywhere, a visionary and freedom fighter non-pareil.

(The author (SS) is a co-founder of LOCOST (Low-Cost Standard Therapeutics, www.locostindia.in). In February 1993, Zafrullah Chowdhury and Rajmohan Gandhi inaugurated LOCOST’s production unit in Vadodara.)

1Note:

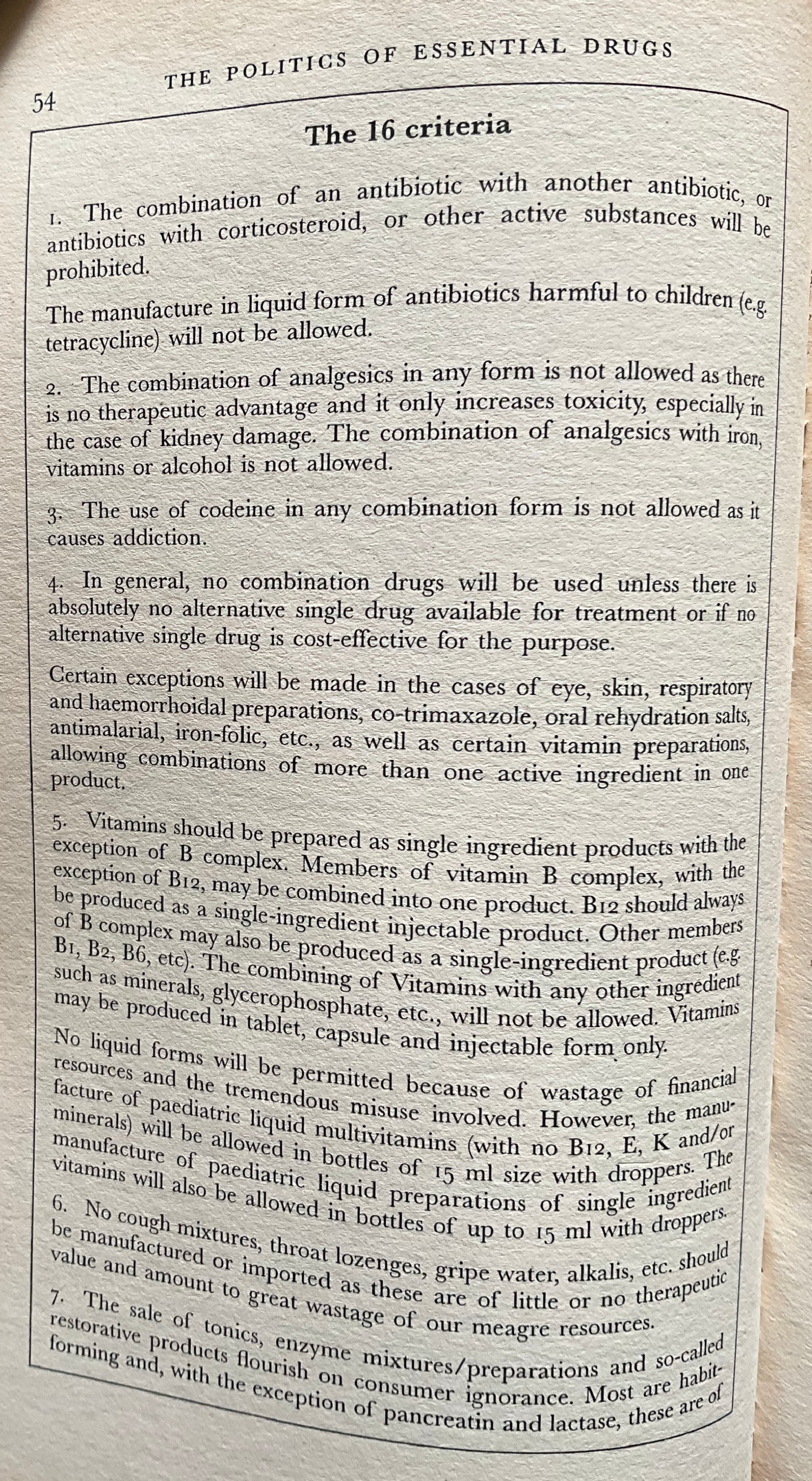

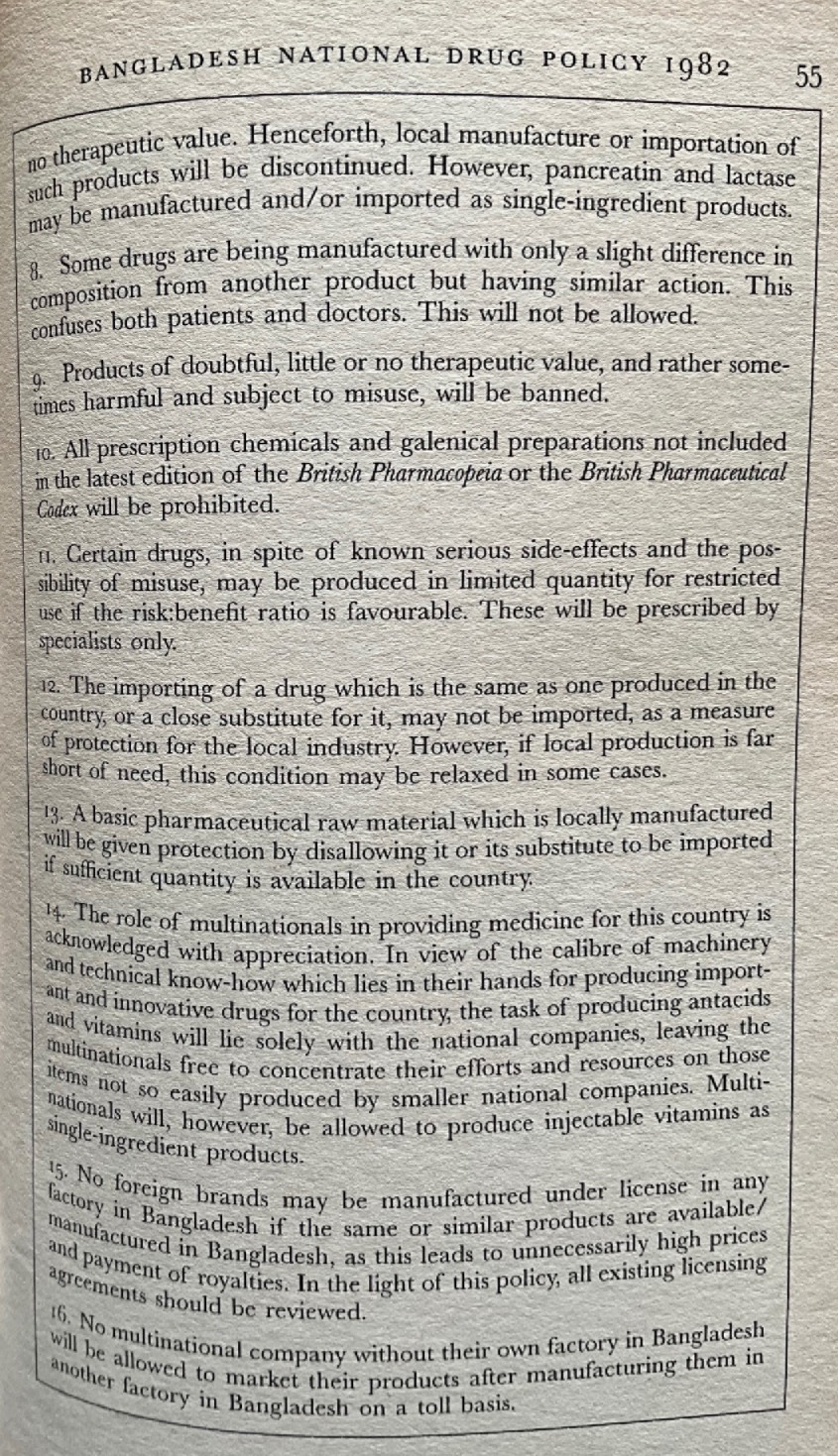

Criteria for withdrawal of irrational and hazardous drugs: the Bangladesh example

In 1982, Bangladesh drew up a list of essential rational drugs, based on a clear set of principles:

As a result of the Bangladesh Drug Policy of 1982, the country had 150 drugs for tertiary care, 45 drugs for primary healthcare, and 12 drugs for village level healthcare. The policy included preparation of a national drugs formulary and price control. These with other measures, the most important of which was strong support from the government, resulted in the reduction of medicine prices over the decade that followed.

Reading recommendations:

1. For a complete articulation of the 16 criteria, and the effect of realpolitik in the dilution of the 1982 Drug Policy, please see Murshid ME, Haque M. Bangladesh National Drug Policy 1982-2016 and Recommendations in Policy Aspects. Eurasian J Emerg Med 2019;18(2):104-109. https://doi.org/10.4274/eajem.galenos.2019.43765

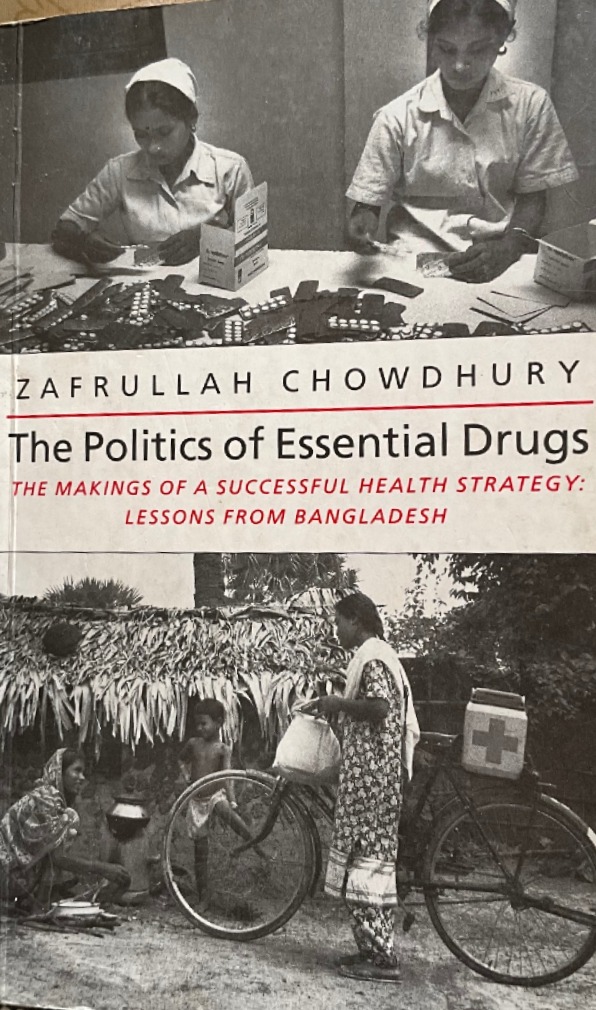

2. For a detailed discussion of the 1982 policy and related events, see: Chowdhury Z. The Politics of Essential Drugs: Makings of a Successful Health Strategy, Lessons from Bangladesh. Universities Press Limited, Dhaka, 1996.

3. For a detailed review of the above book, please see: Srinivasan S. Singing about the dark times-Bangladesh Drug Policy. Econ Polit Wkly, 1996 May 25[cited 2025 April 9]. pp.1252-56. Available from: https://www.epw.in/journal/1996/21/reviews-uncategorised/singing-about-dark-times-bangladesh-drug-policy.html; can be viewed at: https://ijme.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/EPW-REVIEW-SRINIVASAN-Singing-about-the-dark-times-Bangladesh-Drug-Policy.pdf

4. See also: Chowdhury Z. The Bangladesh Drug Policy 1982: A Long History – where are we now? Asia Pacific Conference on National Medicines Policies. Sydney, May 26-29[cited 2025 April 9], 2012. Available from: http://www.locostindia.in/Public_advocacy/index/drug-pricing-related-papers-and-reports, under Bangladesh Price Fixation History.

Supplementary files (all available online only):

The politics of essential drugs — the makings of a successful health strategy: lessons from Bangladesh

This book is the story of the country’s radical national drug policy of 1982 — the historical build-up, what happened when, who tried to derail it, and the upshot more than a decade later.

The 16 Criteria for withdrawal of irrational and hazardous drugs

Authors: S Srinivasan (chinusrinivasan.x@gmail.com), Trustee, Low-Cost Standard Therapeutics (LOCOST), I Floor Premananda Sahitya Sabha Hall, Dandia Bazar, Vadodara 390 001, INDIA.

Conflict of Interest: None Funding: None

To cite: Srinivasan S. Remembering Zafrullah Chowdhury (1941-2023): Reflections on his second death anniversary. Indian J Med Ethics. 2025 Oct-Dec; 10(4) NS: 325-327. DOI: 10.20529/IJME.2025.027

Submission received: April 7, 2025

Submission accepted: April 10, 2025

Published online first: April 11, 2025

Manuscript Editor: Sandhya Srinivasan

Copyright and license

©Indian Journal of Medical Ethics 2025: Open Access and Distributed under the Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits only noncommercial and non-modified sharing in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.