RESEARCH ARTICLE

Homoeopathic medical education in Maharashtra: growth and challenges

Milind Bansode

Published online first on August 28, 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2021.065Abstract

The growth of homoeopathy medical colleges in Maharashtra state has been very rapid post-1985. This has resulted in the state’s having the largest number of homoeopathy colleges in the country. However, not even a single government college of homoeopathy exists in the state, creating a significant gap in the health services system. It is in this context that the pattern and growth of homoeopathy medical education in the state and the contribution of government policies towards their growth is examined in this article. Government policies have facilitated the growth of homoeopathy colleges exclusively in the private sector. This growth is rapid, driven by commercial interest and does not match professional opportunities. The article raises some of the key problems of homoeopathy medical education in the state and calls for efforts towards the improvement of the medical system.

Keywords: Medical education, homoeopathy professionals, commercialisation of medical education, mainstreaming of AYUSH, policies on AYUSH.Background

India’s medical education system has the responsibility of producing medical professionals to serve the healthcare sector. Traditional and alternative systems of medicine referred to by the acronym AYUSH (Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, Sowa-Rigpa, and Homoeopathy) are an integral part of the Indian healthcare system (1) making it pluralistic in nature (2). Consequently, medical education in the allopathic and various non-allopathic systems of medicine together form the totality of medical education in India (2, 3).

AYUSH systems in general and homoeopathy, in particular, have an increasing share in terms of the number of teaching institutions, intake capacity and the number of medical graduates produced every year (4). Maharashtra, the state with the largest number of homoeopathy colleges in the country, is a major contributor to homoeopathic educational infrastructure(4). In this context, the article attempts to analyse the development of this educational sector, the contributing factors, and the perceptions of various stakeholders about this growth, using a qualitative research design.

The study

This article is an extract from the author’s doctoral studyi, which examines homoeopathic medical education, its growth, and professional engagement against the backdrop of the policies of the health services system. The present paper confines itself to the growth of medical education in homoeopathy in Maharashtra state and the contextual factors contributing to it. The data for the study were collected by collating information on all homoeopathy medical colleges in the state and analysing it based on geographical location, year of establishment and ownership of these colleges.

An initial analysis revealed that the exponential growth of colleges of homoeopathy had taken place in the state only in the private sector. This stimulated further exploration using qualitative techniques, where data collection was carried out during the period October 2017 to December 2018, through twenty-four interviews and eight focus group discussions (FGD) conducted in nine out of fifty-four homoeopathy medical colleges (hereinafter HMC) in different parts of the state. The process was accomplished using semi-structured guides, seeking in-depth information on the evolution of homoeopathic medical education, the establishment of the colleges, experiences of participants, their perceptions of the growth of the sector, opportunities and challenges. Further, to triangulate and enrich the data, nineteen key informant interviews (hereinafter KII) were conducted with purposively selected participants, who included officials from the regulatory and monitoring authorities of medical education, former faculty members of teaching institutions, representatives of associations of homoeopathy professionals, and ground-level practitioners. The collected data, consisting of fifty-one transcripts and field notes, were subjected to thematic analysis and the emerging themes are presented as findings of the study.

Research ethics

The author received ethics clearance from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai (Letter dated October 3, 2017) before conducting a field-level inquiry for this study. All the data were collected with prior informed consent from all the participants in the study, including key informants.

The homoeopathic system of medicine

Homoeopathy is an alternative system of medicine preferred for treating acute and chronic illnesses without side effects in a cost-effective manner. It was introduced in India during the early 19th century, by some German missionaries in the eastern part of the country (5 6, 7). Scholars believe that because it was introduced by non-British Europeans, homoeopathy gained acceptability and popularity as a modern yet non-colonial form of medicine (5). Homoeopathy treatment started becoming popular in Bengal with the remarkable results it could produce, particularly in the case of cholera epidemics which led to the conversion of renowned trained allopathic doctors like Dr Sircar to this system (5, 8). It was followed by the opening of homoeopathic dispensaries in Bengal, and the informal training and spread of the practice of homoeopathy in other states. Meanwhile, around 1839, Dr Sir John Martin Honigberger successfully treated Maharaja Ranjit Singh of Punjab using homoeopathy, and its popularity gained further impetus (6).

Following the spread and rising popularity of homoeopathic treatment among the masses, various efforts were made towards its formal recognition. In post-independent India, that resulted in the enactment of the Central Council of Homoeopathy (CCH) Act 1973, towards the regulation of homoeopathy education and practice. For administrative purposes, homoeopathy was brought under the Department of Indian Systems of Medicine and Homoeopathy (ISM & H) in 1995 under the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MHFW), and was further renamed as the Department of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy (AYUSH) in 2003. To provide focused attention towards the development of education and research in these non-allopathic alternative systems of medicine, the Ministry of AYUSH was created in 2014 (9).

Homoeopathic medical education

Formal education in homoeopathy through an institutional set up during the colonial period was marked by the establishment of The Calcutta School of Homoeopathy in 1881, later re-named the ‘Calcutta Homoeopathic Medical College’ (10). The Bengal Provincial Government established the General Council and State Faculty of Homoeopathic Medicine in 1943 offering a diploma course, the Diploma in Medicine and Surgery (DMS). Following the introduction of a separate Bill for Homoeopathy in 1971 and its acceptance by the Rajya Sabha, the Indian Parliament enacted The Homoeopathy Central Council Act, 1973 (CCH Act) to establish a legislative mechanism for the regulation of education and practice in homoeopathy (9, 10). Accordingly, the Central Council of Homoeopathy (CCH) was established in 1974 to bring in uniformity and set down standards for homoeopathic medical education in the country. At present, the CCH approves two courses: the Bachelor of Homoeopathic Medicine and Surgery (BHMS), of five and a half years duration, and the postgraduate degree course ‒ Doctor of Medicine (MD) in homoeopathy ‒ of three years duration (10). As noted in the National Health Profile 2019, as on April 1, 2018, there were 221 homoeopathic medical colleges in the country, with an admission capacity of 16,173 imparting undergraduate level education in homoeopathy (4).

The growth of homoeopathy medical education in Maharashtra

At the time of the formation of Maharashtra state in 1960, there were six colleges of homoeopathy offering formal training, including two in Nagpur and Akola regions, which became part of the new state. Currently, the number of homoeopathic medical colleges established in Maharashtra has reached 54ii , the highest in the country.

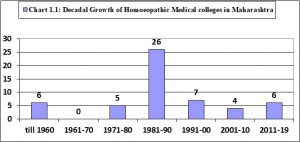

The decadal growth analysis of establishment of homoeopathy colleges [Chart 1.1] reveals that there were only six colleges till 1970, all of which were established before 1960. Only five more homoeopathy colleges were established in the decade 1971-80. This suggests that homoeopathy was not a focus of medical education in the state.

However, there was a sudden rise in the number of homoeopathy medical colleges from 1981–90. This growth was largely due to the private sector’s entry into higher education, which has become a trend across the country and the number of medical colleges started rising substantially. During this decade, twenty-six homoeopathy colleges were founded in Maharashtra, compared to sixteen each for allopathy and Ayurveda. Strikingly remarkable is the fact that in a single academic year (1989–90), sixteen new homoeopathy colleges were established in the state. This was almost two and a half times the number of homoeopathy colleges existing in the state until then, and could have been triggered by other factors developing across the country then, which need greater scrutiny.

The subsequent decades 1991–2000, 2001-10 and so on, saw a steady pattern of growth with four to seven colleges being set up per decade. This observed boom in the number of homoeopathy medical colleges in the private sector, specifically during the 1980s, all in the private sector cannot be justified only in the name of promoting homoeopathy, in the context of rampant cross-system practice (11, 12). Hence, the uncontrolled setting up of such medical institutions has been attributed by Bal (13) to “questionable motives”, because “private colleges make an obscene amount of money” through admissions and “allow rich people …to bypass entrance examinations” (13).

Factors contributing to this fast-paced growth

The growth of homoeopathic medical colleges before the 1960s was the effect of initiatives of like-minded people – influenced and motivated by the efficacy of homoeopathic treatment. Considering the rising demand for homoeopathy education from students, doctors in homoeopathy trained in these colleges, joining hands with resourceful people, started new colleges in their localities and the trend of establishing new privately-run colleges continued.

Policy reforms in the 1980s created a more favourable environment for this growth. The Educational Institution Act, 1983, after adding Section 3A, allowed the admission of students based on capitation fees in private professional colleges in Andhra Pradesh, followed by Karnataka. A similar trend has been followed in Maharashtra, along with southern states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu, which has resulted in the establishment of a large number of private medical colleges (14). The Maharashtra government adopted this policy of allowing the establishment of unaided colleges in 1984, triggering the establishment of the largest number of homoeopathy colleges in the state from 1985-90. The conversion of diploma courses to a bachelor’s degree further supported this trend. A professor of a homoeopathic medical college stated:

In ‘85, that is the time when the BHMS course was started. Prior to that, before ‘83, the courses were of diploma. (….) So, the people who are at [the]top are from that category. (….) They started colleges in their own home towns. They have studied from Amravati, Nagpur, they started colleges in their own towns. HMC 1/ 02/20171126)

The political environment and influential politicians facilitated the growth of new colleges around 1990. This was commented on by a senior faculty member with 38 years of teaching experience:

I told you that, when I took admission, I can say that seven, eight colleges were there. Then in ‘89 when Mr M [name anonymised] was Minister, few colleges were started under his guidance and thereafter the number of colleges is increasing day by day. And Maharashtra state is the state because in India 250 colleges are there and approximately 50 colleges are there in Maharashtra only. So, you can understand the situation of Maharashtra, in comparison with the other states. (KII 06/20180907)

Another contributory factor to the setting up of private homoeopathy medical colleges is the recent policy move to introduce a bridge courseiii for homoeopathy professionals which will enable them to practise allopathy/modern medicine as well. This has been remarked on by a professor of a homoeopathic medical college:

Bridge course is one that… people think that our child will become a homoeopathic doctor in four years, he is easily passing and he can practise whatever he wants. Legally. After completing [the]bridge course, they can practise allopathy, and it is as good as MBBS. (….) This you get in less money, and easy passing, you can do this. Because of that, there is a huge rush to homoeopathy. And because of that only, these colleges are increasing. If there is so much rush, then why not? (KII 05/ 20180825)

Thus, the Maharashtra government’s policy of allowing trained homoeopaths to practice allopathic medicine attracted many more students to homoeopathy education – comparatively cheaper and with less rigorous requirements for admission. By converting BHMS admissions into a backdoor entry to allopathy practice, the state has deviated from its role of encouraging homoeopathy and providing homoeopaths with professional opportunities to practise the system they are trained in. The growth cannot be justified in the name of popularising homoeopathy, as the majority of trained homoeopaths are engaged in practising allopathy, referred to as cross practiceiv (15) which is a serious public health concern.

Privatised growth driven by commercial interest

The rapid growth of homoeopathy colleges has substantially increased the educational infrastructure in the state, however, ownership of these colleges, all in the private sector validates the claim by critics of ‘commercialisation of medical education’ (16). This commercialisation is evident from the narrative of the senior faculty member of a homoeopathy medical college who mentioned,

I have seen all the trustees and this is my clear-cut opinion: all those colleges are not to produce students, rather they are just to earn money from students and give them degrees, knowledge is not given. (….) The condition is like that, there are no patients, no staff; all are running commercial colleges. There is no clear view, I have my clear view; I have to promote and propagate homoeopathy. (KII 17/20181001)

It is striking that despite having the largest number of homoeopathy colleges in the country, there is not a single government homoeopathy college in Maharashtra. All homoeopathy medical colleges are managed by private owners usually in the guise of “charitable trusts/ societies” with a direct or indirect association with political leaders. This substantiates the claim of Nagral that many private medical colleges in India are owned by political leaders (17).

That the political influence and personal economic interests of these leaders have restricted the establishment of government colleges in Maharashtra is borne out by the views of a professor at a homoeopathy medical college, commenting, ‘I think there will be no other reason for me to think [this]other than political interest. Politics and interest.’ On probing further, he added,

Well, it is uhh very uhh unfair on my part to comment on this. Because we are all working in the same field and all. Every politician has his own college. Why would anyone want government college to come in competition with them (giggles). (Pause) I think this should give you a hint to what I am trying to tell. (HMC 3/02/20180907)

This brings into question the role of government and the regulatory authorities at a time when the private sector was making a determined push to establish homoeopathic colleges, without any attempt to ensure the quality of education imparted. Naturally, government initiatives to establish state-run homoeopathy colleges are completely missing or have never materialised.

Uncontrolled growth hampering the quality of homoeopathy education

The majority of participants in this study perceived the existing number of colleges as very much more than required. A senior faculty member of a homoeopathic medical college affirmed,

It is very fast growth of too many colleges, more than what is required, and uhh that is why, the larger number, there has been a decline in the quality of homoeopathic education. Especially in the state of Maharashtra, where there is no single government job available for homoeopathic doctor. We are the only state in India, where there is no homoeopathic job for government, uhh government job for homoeopathic doctors. (HMC 4/01/20180921)

Despite having the largest number of homoeopathy colleges in the country – producing a huge number of trained homoeopathy doctors every year ‒ there are no government jobs for homoeopathy graduates to serve as clinicians in Maharashtra. The meagre job opportunities which opened up after the launch of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in 2005 are hardly attractive, as AYUSH medical officers’ appointments are contractual and not permanent appointments on the government payroll. Thus, the disproportionate increase in homoeopathy colleges is not in tune with the available professional opportunities. This is noted by a senior faculty member, ‘I can say, only this is a word used by the communist leader (…) in a sansad [parliament], in a report. It is called “mushroom-like growth” of homoeopathic medical colleges. This is the authentic sentence in a record of parliament; mushroom-like growth of homoeopathic colleges.’ On asking how he perceived this growth he elaborated further,

It is like that only. Unless and until it is very strictly (pause) monitored and governed by authorities, Laws are there but they are not following [them]. Every time they get some excuses by different channels different methods, and it makes only [a] factory to I can call in my words is a cancerous output of the homoeopaths. Which is immature, imperfect and that’s why they are looking for the bridge course and allopathy to practise because they are not getting proper knowledge. They have not been taught philosophy properly. (HMC 2/01/20180419)

As remarked by Kothari (18), the growth in the number of medical colleges is due to private unaided colleges mushrooming in these fields, which is evident in the state context of homoeopathic medical colleges. A professor at a homoeopathy college asserted,

Well, it’s not right on my part to say this but I can say as far as the quality is concerned, I don’t think even twenty-five per cent colleges have all the minimum required infrastructure, and staff to provide facilities to the students. The condition in some of them is very pathetic, in some, they are better off and twenty-five to fifty per cent colleges are prime. (HMC 3/02/20180907)

Many of the colleges fall short in fulfilling the norms of the monitoring authorities and they strive to get conditional permissions, using any possible means, to admit students. The AYUSH Ministry had denied permission to eleven out of 54 colleges to admit students for the academic year 2018-19 and conditional permissions were given to the remaining 43 colleges (19). Similarly, for the year 2019-20, only 46 of these colleges were permitted to function (20). This raises questions about the fulfilment of norms and standards of these colleges which were either not permitted to function or given such conditional permission. So, the efforts of the regulatory authorities are futile as the norms are followed by very few of the colleges and the quality crumbles further. A senior homoeopathy practitioner, in practice for fifteen years and associated with a homoeopathy colleges for the last 27 years, claimed:

Current scenario, I can only say (…) because of too many colleges in Maharashtra it is almost 47 and now becoming 53 colleges (…). I would say the standard of education has lowered slightly. (….) And those are at periphery not up to the mark and the rules which are coming from AYUSH or CCH they are mainly satisfied by all the colleges in the cities. (….) And I think it is not very easy to close down these colleges to them. But they are taking the steps. It seems that they are going to close down substandard colleges. Once this number of colleges is reduced, we have some growth. (KII 03/20180823)

Participants in the study from the regulatory and monitoring bodies also acknowledge the need to control this growth. On the subject of growth and regulatory mechanisms, an official of the Directorate of AYUSH said:

The growth of educational institutes needs to be there; it should be there. (….) But control should also be there on the growth of educational institutions. In proportion to the growth its supervision, control over them, terms, conditions, its affiliation and recognition also should be there. (…) for this government and university needs to frame good policies and more stringent policy so that this can be controlled. (….) But that does not mean colleges should not be established. Keeping vigilance is important. (KII 09/20181218)

The regulatory role of the state through its monitoring mechanisms is crucial for improving and maintaining the overall quality of homoeopathy medical education. There is a need to adopt strict evaluation and continuous monitoring of the development and quality of homoeopathy colleges in the state.

Discussion

In the Indian context, homoeopathy ‒ often viewed as indigenous ‒ was the other western therapeutic system introduced during the colonial period which faced neglect in the initial post-independence period. Further, despite the recommendations of several committees as noted by Abraham (21), the “Indian state did not actively intervene until 1970s’ in the matter of alternative systems of medicine”, including homoeopathy. It could get the attention of policymakers only in 1971, when a separate Bill for homoeopathy was introduced in the Lok Sabha (10, 21). However, it has continued to be popular among the Indian masses, resulting in the growth and development of homoeopathy education and practice in various parts of the country.

Our analysis of the development of the disproportionately large number of homoeopathic medical colleges in Maharashtra suggests that this trend has been uncontrolled, particularly post-1985. The trend has been further sustained by the Maharashtra government’s policy of allowing the setting up of unaided colleges, the up-gradation of homoeopathy education to the five-and-a-half-year graduation course, and the introduction of a bridge course, rather than utilising the services of homoeopathy graduates by offering them professional opportunities (22). This policy allowed resourceful people with political influence to cash in the demand for medical courses (16), and provided easy and low-cost human resources in the form of trained doctors for allopathic hospitals (22). For students, easy access to admission into medical courses created a demand for homoeopathic medical education in the state which, in turn, stimulated the establishment of more such colleges in the state.

In this context of uncontrolled, commercialised growth of homoeopathic medical education in the state, poor infrastructure, insufficient staff, full-time staff existing only on paper and lack of a hospital facility are issues of serious concern (23). It must be noted that the lack of adequate facilities reduced homoeopathic medical education in the state to mere theoretical classroom training. Such deficient training could hardly produce effective potential practitioners of homoeopathy. Hence homoeopathy education needs to be revamped with an emphasis on clinical applications and not mere theoretical training (24). The participants in our study ‒ stakeholders of homoeopathic medical education and supporters of homoeopathy ‒ expressed the demand for action against substandard colleges and restrictions on the number of homoeopathic medical colleges in the state. The efforts of the AYUSH department towards standardisation and restriction of permissions to such colleges are a welcome step, but more determined efforts are required. Among them are:

• Ground-level implementation of stringent guidelines and continuous monitoring (25) to reform medical education which has become a “money-making business” (26).

• Active government patronage for the homoeopathy system is crucial for its genuine development. With the current low social status of homoeopathy both as an educational stream and a healthcare system, it is opted for as a “last resort”. Furthermore, the state government has neither opened its own college of homoeopathy nor provided any financial support to the existing colleges.

• Government jobs need to be provided for homoeopathy doctors as clinicians and with a separate homoeopathic healthcare delivery infrastructure. Currently the state has only a single government homoeopathic hospital at Mumbai, offering homoeopathic treatment and healthcare facilities. This has implications for the poor access that the population has to homoeopathic treatment and the inadequate opportunities for those trained in the homoeopathic system of medicine to practise and contribute to public health.

Against this background of lack of state support and professional opportunities for homoeopathy practitioners to serve as clinicians, a majority are found engaged in cross-practice. On the one hand, it affects the quality of allopathic care they offer since they are not professionally trained in allopathy, and it adversely impacts their morale and professional identity as “homoeopaths” and their competence to practise homoeopathy. On the other hand, the government is found to be adopting the policy of allowing allopathic practice by trained AYUSH doctors which is a serious ethical concern.

Conclusion

Homoeopathic medical education in Maharashtra state has been facing neglect from the policymakers in terms of consistent long-term planning, while encouraging uncontrolled growth and commercialisation of homoeopathy colleges. Mere numerical growth of colleges is hardly conducive to producing professional homoeopaths with the capacity for practising homoeopathy. Further, the lack of government patronage for homoeopathy education is evident where there is no government homoeopathy medical college in Maharashtra, despite having the largest number of homoeopathy colleges in the country. Besides, the existing healthcare delivery system offers very little scope for practising homoeopathy – resulted in engagement in cross-practice to a large extent – which is a serious ethical and public health concern. So, the growth of homoeopathy, as a system of medicine needs to be actively supported by government. For any system to prosper, government support, acknowledgement and societal recognition is a prerequisite. Hence it demands a more active role for the state influencing the social status of homoeopathic medical education through serious review, providing professional opportunities, and support for its further development.

Funding support: The author received a UGC RGNF fellowship during his PhD study. No other sponsorship or funding was received for this work

Conflicts of interest: None declared

Acknowledgements: The author would like to acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their perceptive comments which have immensely benefited the paper and to thank Prof Mathew George for his mentoring, encouragement and the valuable inputs he offered towards improving the study.

____________________________Notes:

iThe study titled, ‘Medical education and healthcare services: A study on homoeopathic medical colleges and professionals in Maharashtra,’ was submitted to the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai on April 24, 2020.

iiBased on the official list of all homoeopathic medical colleges affiliated to Maharashtra University of Health Sciences (MUHS), Nasik, received on December 28, 2018.

iiiOn August 13, 2014, the Government of Maharashtra approved the one-year certificate course in “Modern Pharmacology” for registered homoeopathy practitioners in the state.

iv“Cross-practice” refers to a complete shift by medical practitioners from one system of medicine to another in which they are not trained. This would apply to homoeopathy doctors when they start presenting themselves as “allopathic practitioners”, carrying out routine prescribing of allopathic medicines, giving injections, antibiotics, intravenous fluids and so on.

References

- NITI Aayog, Government of India. A Preliminary Report of the Committee on the Reform of the Indian Medicine Central Council Act 1970 and Homoeopathy Central Council Act, 1973. New Delhi: GoI; 2017. [cited 2020 Oct 10]. Available from: https://niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/document_publication/Preliminary_Report_of_Committee_AYUSH.pdf

- Abraham L. Social History of Medical Education (Indian Systems of Medicine). Research Report Submitted to the Board of Research Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai;1999.

- Singh A. Restructuring medical education. Econ Pol Wkly. 2005; 40(34): 3725-31.

- Central Bureau of Health Intelligence, Govt of India. National Health Profile 2019 14th Issue. New Delhi: CBHI; 2019 [cited 2020 Oct 15]. Available from: http://cbhidghs.nic.in/showfile.php?lid=1147

- Frank R, Ecks S. Towards an Ethnography of Indian Homeopathy. Anthropol Med. 2004; 11(3):307-26.

- Gupta, N. An Overview of the Current Status of the Homeopathic System of Medicine in India and the Need to Achieve Its Best. The Homoeopathic Heritage. 2012 Aug; 38: 39-42.

- Ministry of AYUSH. Homoeopathy Science of Gentle Healing. New Delhi: Min of AYUSH; 2015.

- Singh DK. Cholera, Heroic Therapies, and Rise of Homeopathy in 19th Century India. In: Kumar D, Basu R, eds. Medical Encounters in British India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 2013. Chapter 6.

- Ministry of AYUSH, Government of India. About the Ministry. New Delhi: Government of India: 2020. [cited 2020 Feb 15]. Available from: http://ayush.gov.in/about-us/about-the-ministry.

- Ghosh AK. History of Development of Homoeopathy in India. Indian J of History of Science (IJHS). 2018; 53(1):76-83.

- Bada Math S, Moirangthem S, Kumar CN. Public health perspectives in cross-system practice: past, present and future. Indian J Med Ethics. 2015 Jul- Sep: 12(3):131-6.

- Chandra S, Patwardhan K. Allopathic, AYUSH and informal medical practitioners in rural India–a prescription for change. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2018; 9(2):143-50.

- Bal A. Medicine, merit, money and caste: the complexity of medical education in India. Ind J Med Ethics.2010 Jan; 7 (1):25-8. Doi: 10.20529/IJME.2010.009.

- Bajaj J. Medical Education and Health Care: A Pluridimensional Paradigm. Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study; 1998.

- Jesani A. Cross practice at the cross-roads. Issues Med Ethics.1996; 4(4):103-4.

- Ananthakrishnan N. Medical education in India: Is it still possible to reverse the downhill trend? Nat Med J India. 2010; 23(3):156-60.

- Nagral S. Medical Council of India under parliament scrutiny symptom documented, but what about the disease? Econ Pol Wkly. 2016 Apr 2; 51(14):18–21.

- Kothari, V. Private unaided engineering and medical colleges: consequences of misguided Policy. Econ Pol Wkly. 1986; 21(14):593–96.

- Ministry of AYUSH, Government of India. List of Homoeopathic Medical Colleges Which have been Granted Conditional Permission by the Central Government for Taking Admission in UP/PG Courses for the Academic Session 2018-19. New Delhi: GoI;2018.

- Ministry of AYUSH, Government of India. List of Homoeopathic Medical Colleges Which have been Granted Conditional Permission by the Central Government for Taking Admission in UP/PG Courses for the Academic Session 2019-20. New Delhi: GoI. 2019.

- Abraham L. Indian Systems of Medicine (ISM) and Public Healthcare in India. In: Gangolli L, Duggal R, Shukla A, eds. Review of Health Care in India. Mumbai: CEHAT. 2005: 187-223.

- Bansode M, Rai J, George M. AYUSH and Health Services Policy and Practice in Maharashtra. Econ Pol Wkly. 2018; 53(37):20-24.

- Forum of Homeopathy Physicians for Excellence in Homeopathy Education (FHPEHE). Improve Standards of Homeopathy Education in India. An online petition at change.org, [Internet] Date unknown [cited 2020 Oct 12]. Available from: http://chng.it/PQjxGRHQY9

- Sankaran R. Homoeopathic Education and Training: Problems and Possible Solutions. A talk by Dr Rajan Sankaran [Internet]. 2016 June; at LIGA, Delhi. [cited 2020 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4vMi24IUdM4

- Samal J, Dehury R. An Evaluation on Medical Education, Research and Development of AYUSH Systems of Medicine through Five Year Plans of India. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2016 May; 10(5): IE01-IE05.

- 26. Deo M. Doctor Population Ratio for India-The Reality. Indian J Med Res. 2013 April; 137:632-5.