CASE STUDY

Ethical dilemmas in mental health resources for college students: A reflective case study

Kangkana Bhuyan, Bhavishya Kalyanpur, Debasmita Phukan, Shafeer KV, Suma T Udupa, Avinash G Kamath, Gayathri Prabhu

Published online first on September 29, 2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2020.100Abstract

Poised to have the highest number of young people in the world, India will have the onus of providing adequate mental health resources to a demographic considered among the most vulnerable with regard to mental well-being. While the Mental Healthcare Act 2017 pushed for greater accountability and care in supporting individuals with mental illness, these directions were specific to services provided by the state and did not address the care required in non-hospital settings. Since many manifestations and repercussions of mental health issues in young people occur in educational institutions, it becomes vital to address ways in which we can formulate ethical mental health services at those sites. This article is a reflective case study of the ethical dilemmas and challenges around issues of confidentiality and quality of care in relation to demand, contributing to a larger mental health ecology involved in providing mental health resources at the Student Support Centre, Manipal, that caters exclusively to students in an Indian campus town.Key words: Mental health resources, student counselling, campus mental health, confidentiality, college students

Higher education and mental health ecosystems

It is widely recognised that the campaign for mental health resources for the age group 18–29 years has to move to a second stage – for the first stage (awareness of the seriousness of the problem) has been sufficiently established (1). The World Health Organization has run sustained drives to draw attention to the fact that half the mental illnesses in the world occur before the age of 14 and three quarters by the mid-20s (2). This being acknowledged, the second stage then is to identify, create, and segment the resources, for not all population strata either suffer equally or need the same tools. This is particularly complicated in a country such as India, with its inadequate resources: only 0.3 psychiatrists, 0.12 nurses, 0.07 psychologists, and 0.07 social workers are available to cater to every 100,000 people (3); these figures are alarming especially considering that the country is poised to have the highest number of young people in the world – 34.33% of India’s total population in the 15–34 years age group in 2020 (4). The National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS) has estimated the current prevalence of mental disorders in the age group of 18–29 years at 7.39 per cent (excluding tobacco use disorder) and lifetime prevalence at 9.54 per cent (5). A recent study in the 15–24 years age group in the state of Himachal Pradesh revealed that adolescents suffered from a wide range of mental health conditions like depression (6.9%), anxiety (15.5%), tobacco use (7.6%), alcohol use (7.2%), and suicidal ideation (5.5%), requiring urgent interventions (6). While this is valuable epidemiological data and provides insight into the demographic group, ultimately a bridge has to be built to address specific individual sites and institutions where these issues have to be comprehended and negotiated. This sentiment has also been reflected in recent case studies and policy reviews (7, 8). Chadda suitably notes that any strategy aimed at improving the mental health of the youth needs to target the areas of service gaps, and educational institutes are the primary sites of such required change (7).

The recently enacted Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 (MHCA 2017) that pushes for quality care for those with mental illnesses – while being progressive and rights based – has placed the onus on the state and lacks directions on how care is to be provided in non-hospital based settings (9). This is a particularly vexing question in the context of the educational sector where the services provided (imparting of knowledge and/or training for a vocation) is not explicitly part of the healthcare sector but is determined by and bears a moral obligation to the emotional well-being of the young people who are accessing these services. Covey and Keller in the Cambridge Handbook of Applied Psychological Ethics (10) specify five main ethical dilemmas in providing mental health services to college students:

-

• increased demands for services without a concomitant increase in staff;

• increase in severity of the psychological problems in students;

• issues related to confidentiality and record keeping;

• variable training levels related to serving a diverse population; and

• technology changes and student expectations (eg, immediate availability of practitioners via social media).

They also identified the following contextual factors (for students in North America): rise in college enrollment, increase in tuition, changing parental styles, and decrease in availability of community mental health resources (10). It seems intuitive that similar complexities and trade-offs would be evident in the Indian context, as well: for example, the variability in training, diversity of student population, and demands of confidentiality. The higher education scenario being widely disparate in India, it remains a challenge to map similar ethical dilemmas in mental health services provided to college students. This paper is a preliminary effort to explore three concrete ethical dilemmas – issues of confidentiality, quality of care in relation to demand, and the requirements for a contribution to a larger mental health ecology – which arose in the functioning of one particular psychotherapy resource in the campus town of Manipal in Southern India in the first two years (2017-2019) after it was set up. In doing so, this reflective case study seeks to open up and catalyse further deliberations among educationists and mental health professionals and, hopefully, lead to policy interventions, including the setting up of more such resources to cater to the constantly growing demand for mental health support for college students.

Reimagining the wheel of mental health support

The Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) offers programmes in several disciplines (including health sciences, engineering, commerce, hospitality, humanities) to approximately 25,000 students enrolled in undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral studies at its primary campus in Manipal, Karnataka. The departments of psychiatry and clinical psychology in its reputed teaching hospital, Kasturba Medical College and Hospital, have been the main source of support and treatment for students with any mental health difficulties. The Directorate of Student Affairs (DSA) of MAHE has also maintained a team of counsellors for students to approach. However, in the face of growing incidence of mental health issues (a world-wide occurrence) and the reluctance of several students to seek help in a hospital setting, the need was felt for a centre that would cater exclusively to students (unlike the hospital, which has clients of all ages and from all backgrounds) and offer confidential support from clinically trained psychologists. A resource was needed to provide students the option of sustained psychotherapy, in addition to existing counselling facilities on campus. This resource was named the Student Support Centre (SSC) and became functional on April 1, 2017. It took about six months of preparatory work from initial approvals to its first day of functioning and was made possible by the involvement and support of several stakeholders and administrative officials. With the support of the hospital, SSC also offered students the added advantage of consultations with psychiatrists in the same comfortable and familiar location as their psychotherapy sessions.

All students supported by SSC, Manipal, are enrolled in a higher education degree course from undergraduate to doctoral research, an age group that ranges from 17 to 42 years (Mean = 20.8, SD = 2.39). Of the total 953 new registrations between April 2017 and July 2019, 570 are women (60%) and 383 are men. This follows the pattern of women seeking mental health services more consistently than men as noted in the World Health Organization report on Gender and Mental Health (11, 12). Of the student clients at SSC, 18% were referred for psychiatric consultations based on the level of distress and impairment in functioning. Some clients also specifically requested a consultation with a psychiatrist, which was arranged for them.

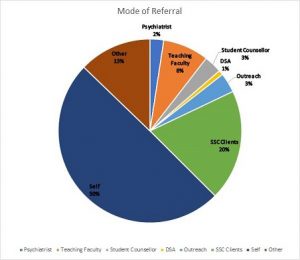

Data collected for referrals indicated that nearly 50% of the students reached out to the centre on their own initiative, followed by referrals from other SSC clients (20%) (Fig. 1). Students are likely to have learned about the Centre from college brochures and pamphlets distributed during the admission process, from faculty members during college orientations, and through social media platforms. Coverage of SSC events by student-run local media may also have helped spread the word. Teaching faculty referred 8% of the registered clients. Psychiatrists and student counsellors referred 2% and 3% of the students, respectively. Outreach programmes by the centre garnered another 3% of the referrals. The DSA referred 1% of the students. Finally, the remaining 8% were referred by friends and family members. The overwhelming trend of students directly reaching out to mental health professionals is noteworthy.

Fig 1: Mode of referral of students

Over the two years of the SSC’s growth, several ethical considerations had to be negotiated, of which three broad areas will be the focus of our paper: (a) confidentiality, privacy, and record keeping, (b) operations and services that can match the growing demand without compromising quality of care, and (c) catering to a specific demographic with an awareness of its inherent “ecology” or “the ecological approach” (as defined by the American Psychological Association) (13) that invites community participation while protecting client privacy.

Ethical dilemmas of confidentiality, privacy, and safekeeping of records

Students typically join higher education at the age of eighteen, ie at the threshold of legal adulthood. This immediately causes possible points of friction – for example, the student might now legally be an adult but is still indebted in many ways (psychologically, financially) to their parents. Different countries have sought to address this dilemma in their own way: for example, in the United States, legal provisions such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (14) and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (15) protect the privacy rights of students with regard to their mental health records. There being no such clarity in the Indian legal or education system (9), the default for the higher educational system has mostly remained the paternalistic model with close supervision and record keeping, for example, sufficient classroom attendance or strong academic performance is seen as the primary signifier of robust mental health, but ground-level realities demonstrate this is not always the case. Indeed, a functional and high-achieving student might well be struggling with debilitating anxieties. The ethical difficulty then for any mental health resource model would be to be wary of this common assumption that good academic performance signifies good mental health.

With these possibilities in mind, a conscious decision was taken to delink SSC work from both hospital and academic records. Although SSC has to often liaise with academic, administrative, and hospital authorities, the primary commitment and priority remains the privacy of its student client (unless the student wishes otherwise or is at risk of harm to self or others). The centre has had to deal sensitively with the issue of access for all students who need its services, since a majority of students depend on their families for funding. Students may not want their families to know right away that they are in therapy. Since its inception, SSC has a nominal billing system (via existent student insurance where possible) and does not collect any charges from students. This protects them from families automatically knowing that students are in therapy, thus leaving the choice of disclosure to students.

As an extension of this question of accessibility and privacy, SSC planned its physical location and design so as to ensure that it was conducive to psychotherapy and represented a progressive approach towards mental health. Phelps et al observed that “a poorly designed counselling area may reduce the quality of the interaction between patient and counsellor . . . Making efforts to provide a less clinical environment may have benefits for all” (16). Multiple studies have highlighted barriers to students seeking help, including lack of time, concerns for privacy and confidentiality, stigma, and lack of openness (17, 18, 19, 20). SSC is located in a quiet residential area, modified to ensure privacy and accessibility (Fig 2). SSC’s physical space has three configurations: the therapy and consultation rooms, shared areas such as the waiting lounge (for clients) (Fig 3) and work-stations (for staff), and areas for community activities such as the discussion hall, and an open pavilion for those seeking a safe space for alone-time. The original architecture of the buildings included features characteristic of the region, such as wood rafters, red-oxide floors, and tiled roofs. These were retained to keep the space welcoming and organic in design. Similarly, the interiors were planned to extend the same warmth, with open conversation spaces, wall art by student artists, thoughtfully compiled bookshelves, and inviting seating arrangements. In a conscious effort to avoid discussions “across a table” all the therapy rooms have an open design plan, without the barricades of furniture, where every effort has been made for the client to feel welcome, safe, and comfortable and to support a positive frame of mind.

The efficacy of the physical space and the confidentiality of the proceedings (for any mental health centre) are equally dependent on the ethical considerations of record keeping. As Covey and Keller discuss in detail, there are often inadvertent conflicts between assuring privacy to a student client (hence, encouraging them to seek help) and the educational institution’s right to know about “at-risk” behaviour so that they can keep the student and their peers safe (10). These ethical issues were discussed in deciding best practices for record keeping at SSC. The psychotherapists at SSC carry the responsibility of maintaining records on the clients. Record keeping procedures and limits of confidentiality are discussed with the client in the first session. The records involve accurate information on clients, like details of first contact, informed consent and the therapeutic contract, the nature of presenting complaints, diagnoses, progress notes, and the type of service provided. The clients’ request for what should be entered in the file is also taken into consideration. The records carry other details like the socio-demographic information of the client, sessions’ dates, and findings of psychological assessments, where necessary.

The records at SSC are maintained in both physical and electronic formats, the latter being password protected with access provided only to treating therapists. The physical file is made available to the treating psychiatrist when needed. The details of prescription when applicable and the psychiatrists’ notes are also maintained in the physical file. Disclosure of information, when necessitated, is carried out with the consent of the client. This may include a brief clinical presentation, any formal diagnosis, and the treatment progress. Physical files are stored in the record room, the access to which is limited only to the personnel of SSC. These files are organised in a chronological order, rather than in any defined cluster (say, the name of the student’s institute), and are updated regularly.

It has been observed at SSC that the assurance and diligent maintenance of privacy of the student-client (which they are aware of) has paradoxically encouraged them to be more open and willing to talk about their experiences with the community, and is a welcome move towards addressing the taboos around mental illness.

Ethical dilemmas in balancing quality care with exponentially growing demand and priority cases

Taking into consideration that mental health resources and professionals in India have always been outweighed by demand, a central ethical dilemma is to balance ongoing quality of care often stretching resources while also being accessible to new clients. This aspect has also been enumerated by Covey and Keller, “The issue of supply and demand in and of itself is not an ethical dilemma as long as alternative care is available, but the process of psychologists making the determination of which students receive what type of care can easily become one.” (10). To be cognizant of this and in line with standards of modern ethical clinical practice, SSC has made efforts to collect anonymised feedback from clients about its services. Lambert and Shimokawa have emphasised this requirement, as a way of understanding processes that work and, more importantly, processes that do not work (21). Since its early days, several methods have been tried to ensure feedback from all SSC clients, initially through anonymous surveys sent through email. Only 174 out of 953 clients from the initial two years had filled the emailed feedback form. To get more responses SSC is now using an electronic tablet for clients to fill the feedback form when they visit the Centre for their sessions, care being taken to ensure that clients have the necessary privacy and do not feel pressurised during the process.

Recurrent feedback has been provided by clients on how difficult it is for students (including ongoing clients) to schedule appointments due to long waiting periods. Although this is a common problem across the country due to the dearth of mental health professionals, it is also possible that a contributory factor for SSC is the high number of unused appointments owing to clients cancelling appointments without prior notice or “no-shows”. While not being charged directly for the services may have encouraged students to seek help, it is likely that this may have also reduced a sense of responsibility on their part to keep their appointments. In this context, it would be desirable to establish a uniform cancellation policy (22). While it is understandable that clients would like to see their therapists more often (with a smooth process towards a slot of their choice), the reality for the SSC is that it has to accommodate a fast-growing demand for mental health support from a sizeable student population.

Discussions among the SSC team members repeatedly brought to the fore their difficulty in balancing the inflow of new clients with ongoing clients, particularly during the middle or end of a semester. An average of five new clients contact SSC for appointments during a single day in the middle of a semester, and an appointment may not be available for up to ten days or even two weeks at peak time. While SSC was never designed to deal with emergency situations – such cases being redirected to the hospital – and this is communicated clearly to the community, there are nonetheless several students who contact the centre in distress and cannot be put on hold because of the unavailability of appointments. Taking this into consideration, SSC now reserves slots each day for new clients who contact SSC in a state of evident distress. It also arranges to see ongoing clients for short sessions (30 minutes) so as to offer reasonable support till a longer appointment can be booked at the earliest availability. The full session would normally run for 50 minutes. Even though SSC functions with empathy for the needs and nature of its client base, it is also vital for any such service to consider the working conditions of the service providers (psychologists and psychiatrists) and the number of therapy sessions that can be comfortably conducted on any given day; this is an ongoing negotiation for SSC.

In recent months, SSC has started to conduct group therapy sessions on issues such as social anxiety and interpersonal effectiveness. While this has not reduced the number of clients who require individual psychotherapy, it clearly brings a more nuanced and varied dimension to care. Nonetheless, the ratio of therapist to client is likely to become an increasingly critical challenge in the future.

Ethical dilemmas of mental health services catering to a student demographic in a restricted geographical area

In its recent guide Student Mental Health, the American Psychiatric Association emphasised the importance of a “fully actualized campus ecology model” for effective application of mental health clinical and programmatic expertise. “An ecological approach assumes that mental and physical health and wellbeing are interwoven with all aspects of campus life and campus infrastructures.” These multiple components of campus life – its various inhabitants, the academic environment, physical environment, cultural environment, socio-developmental environment, values, norms, and traditions of the university community – are in interplay with each other (23). This notion of mental wellness as catering not only to an individual case but being dependent on and having reverberations in that individual’s community is increasingly gaining traction; similarly, the idea of psychotherapy as being not just remedial but enabling overall positivity is also gaining ground (24, 25).

Even though SSC deals with a considerable diversity in its clientele – for instance, in terms of age, class, gender, sexuality, and nationality – there is certainly a sense of homogeneity because of its location in a two-kilometre radius campus town and because all its clients are enrolled in higher education. Being amidst thousands of students on campus can offer some degree of anonymity, but the geographical containment of these numbers also involves a fair amount of visibility among student clients as well as possibilities of encountering their psychologists in social non-therapy settings. The ethical quandary then involves ensuring best possible privacy and service to individual student clients, while opening up the physical space of SSC to the larger community irrespective of whether they are clients or not, so as to account for interplays in the ecology of mental health.

In seeking to foster this wider mental health eco-system, SSC set up a Student Advisory Board comprising of young mental health advocates in the student community, several of the members having been clients of SSC as well. The Student Advisory Board meets at regular intervals to discuss their role as a peer referral system and to keep the activities of the resource as student-centric as possible. One of the key responsibilities of these mental health advocates is to sustain the ecological model by working towards making SSC not just a resource to seek help or helpful conversations from but also a space for celebrating creativity, initiative, and community spirit. Among the outreach events organised thus far are art exhibitions, music concerts, poetry recitations, reading circles, painting sessions, and so on. This organic extension of the Centre’s work into advocacy and allied activities that support overall mental well-being is one of the two chief innovations of SSC in terms of mental health support at educational institutions in India. The other key innovation is offering students access to psychiatric consultations at the same (non-hospital) location as their psychotherapy sessions. This design has been possible because of the commitment of the administration to offering resources of space, personnel, and outreach activities.

As has been studied and commented in various contexts, the interests of the administration (close supervision, intervention) do not always ethically align with the interests of a student client who may desire privacy and autonomy. However, the case study of SSC serves, in this instance, to highlight two strong features in its framework that may be worth retaining as a possible model for other such ventures: first, ensuring the autonomy of the centre in its daily functioning and record keeping; second, highlighting the moral responsibility that any institution (family, state, college) bears towards the holistic mental growth of its young population by keeping it student-centric and remaining sensitive to the swiftly evolving ground realities and pressures of higher education in India. There is no doubt that the mismatch between demand and the commitment to mental health (in terms of financial priority and personnel choice) will only continue to grow if it is not addressed at the highest governmental and educational levels – it might thus be salutary to learn from the successes and challenges that this particular case study encountered.

Competing interests and funding support: None to declare.References

- Christensen H, Reynolds Rd CF, Cuijpers, P. Protecting youth mental health, protecting our future. World Psychiatry. 2017 Oct; 16(3): 327-8.

- World Health Organization. Adolescents and mental health. Geneva: WHO; 2017 [cited 2019 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/mental_health/en/

- World Health Organization India. Mental health in India. Geneva: WHO; date unknown [cited 2019 Mar 30]. Available from: http://origin.searo.who.int/india/topics/mental_health/about_mentalhealth/en/

- Central Statistics Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, GoI. Youth in India. New Delhi: CSO; 2017 Mar[cited 2019 Mar 30]. Available from;https://www.thehinducentre.com/multimedia/archive/03188/Youth_in_India-201_3188240a.pdf

- Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao GN, Pathak K, Singh LK, et al. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16: Prevalence, patterns and outcomes. National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences. NIMHANS Publication, no. 129. Pp.90-121.

- Gururaj G, Pradeep BS, Beri G, Chauhan A, Rizvi Z. Adolescent and Youth Health Survey– Himachal Pradesh 2014. Bangalore: Centre for Public Health, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences; 2014 [cited 2019 Mar 30]. Available from: http://nimhans.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/HP-Youth-Health-Survey-Report_3rd-Draft_15-05-2015.pdf

- Chadda RK. Youth & mental health: Challenges ahead. Indian J Med Res. 2018; 148(4):359.

- Roy K, Shinde S, Sarkar BK, Malik K, Parikh R, Patel V. India’s response to adolescent mental health: A policy review and stakeholder analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019; 54(4): 405-14.

- Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India. The Mental Health Care Act, 2017Apr 12[cited 2019 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2249/1/a2017-10.pdf

- Covey MA, Keller KJ. Ethical issues in providing mental health services to college students. In: Leach M, Welfel E, editors. The Cambridge Handbook of Applied Psychological Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2018. p 47.

- World Health Organization. Gender and mental health. 2002

- Oliver MI, Pearson N, Coe N, Gunnell D. Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005; 186(4): 297-301.

- American Psychological Association. Multicultural guidelines: An ecological approach to context, identity, and intersectionality. 2017[cited 2020 Sep 25]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/about/policy/multicultural-guidelines.pdf

- The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). (20 U.S.C. § 1232g; 34 CFR Part 99). Available from: https://www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/fpco/ferpa/index.html

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/hipaa.html

- Phelps C, Horrigan D, Protheroe LK, Hopkin J, Jones W, Murray A. “I wouldn’t classify myself as a patient”: the importance of a “well-being” environment for individuals receiving counseling about familial cancer risk. J Genet Couns. 2008; 17(4): 394-405.

- Givens JL, Tjia J. Depressed medical students’ use of mental health services and barriers to use. Acad Med. 2002; 77(9): 918-21.

- Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein, E, Zivin K. Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Med Care Res Rev. 2009; 66(5): 522-41.

- Komiya N, Good GE, Sherrod NB. Emotional openness as a predictor of college students’ attitudes toward seeking psychological help. J Couns Psychol. 2000; 47(1): 138.

- Mowbray CT, Megivern D, Mandiberg JM, Strauss S, Stein CH, Collins K, et al. Campus mental health services: Recommendations for change. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006 Apr;76(2), pp.226-37

- Lambert MJ, Shimokawa K. Collecting client feedback. Psychotherapy(Chic). 2011 Mar; 48(1):72.

- Gans JS, Counselman EF. The missed session: A neglected aspect of psychodynamic psychotherapy. J Psychotherapy. 1996; 33(1):43-50.

- Roberts LW. Student mental health: A guide for psychiatrists, psychologists, and leaders serving in higher education. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

- Sheldon KM, King L Why positive psychology is necessary. Am Psychol. 2001 Mar; 56(3): 216.

- Schneider SL. In search of realistic optimism: Meaning, knowledge, and warm fuzziness. Am Psychol. 2001 Mar; 56(3): 250.