ARTICLES

Ethical dilemmas experienced by clinical psychology trainee therapists

Poornima Bhola, Ananya Sinha, Suruchi Sonkar, Ahalya Raguram

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2015.055

Published online: August 12, 2015

Abstract

Ethical dilemmas are inevitable during psychotherapeutic interactions, and these complexities and challenges may be magnified during the training phase. The experience of ethical dilemmas in the arena of therapy and the methods of resolving these dilemmas were examined among 35 clinical psychologists in training, through an anonymous and confidential online survey. The trainees’ responses to four open-ended questions on any one ethical dilemma encountered during therapy were analysed, using thematic content analysis. The results highlighted that the salient ethical dilemmas related to confidentiality and boundary issues. The trainees also raised ethical questions regarding therapist competence, the beneficence and non-maleficence of therapeutic actions, and client autonomy. Fifty-seven per cent of the trainees reported that the dilemmas were resolved adequately, the prominent methods of resolution being supervision or consultation and guidance from professional ethical guidelines. The trainees felt that the professional codes had certain limitations as far as the effective resolution of ethical dilemmas was concerned. The findings indicate the need to strengthen training and supervision methodologies and professional ethics codes for psychotherapists and counsellors in India.

Introduction

At different stages of their professional journey, therapists are inevitably confronted and troubled by choices between “right versus wrong” and “right versus right” (1). Intrinsic to therapeutic interactions are the negotiation of the balance between the “person” of the therapist and his/her professional role, the fact that the therapist–client encounter takes place in a private space, and the inherent power imbalance between the therapist and client. All these contribute to the emergence of ethical dilemmas. Ethical dilemmas are ubiquitous in therapy (2) and represent the experience of an apparent conflict between alternatives, neither of which is completely acceptable. The choice of any one action inevitably results in some ethical principle being compromised.

Trainee therapists grapple with the complexities and challenges of shifting from the known role of the lay helper to the unknown role of the professional (3). The anxiety of trainee therapists, meeting clients and supervisors for the first time (4, 5), makes them particularly vulnerable to a range of difficulties. Findings from the International Study of the Development of Psychotherapists (6) indicate that inexperienced therapists experience more challenges than do practitioners at later stages of professional development. These challenges include feeling troubled by moral or ethical issues during interactions with clients.

Ethical issues are often complex, multifaceted, and do not always have unambiguous answers (7). Professional ethical guidelines tend to vary in the degree of detail and are regulated differently by professional organisations or legal systems in different countries. Academic and professional psychology training programmes in India usually refer to the American Psychological Association (APA) code (8). This incorporates both core ethical principles and detailed guidelines and is periodically revised. Clinical Psychologists in India are required to register with the Rehabilitation Council of India (RCI) but the RCI ethics code is brief and not tailored specifically to the psychotherapist–client context. The Indian Association of Clinical Psychologists (IACP) has recently revised its ethics code from the earlier 1995 version and included several newer ethical challenges like the use of e-therapy (9). However, it does not include information contained in some sections of the APA code, related to providing services in emergencies, delegation of work, fees, termination and processes for reporting ethical violations. Other sections, for example those related to practitioner competence and therapist–client sexual intimacy, are less detailed in the IACP code than in the APA code. Besides, only a subset of clinical psychologists in India is part of the IACP and this limits awareness of the organisation’s ethics guidelines. The ethical guidelines of the National Academy of Psychology in India provide a very brief “moral framework”. This emphasises principles and values such as respect for the dignity of people, caring for the well-being of people, integrity, and professional and scientific responsibilities to society. In sum, most international and national codes are lacking in clear guidelines on the process of ethical decision-making to be followed when faced with tough choices. In India, in particular, the absence of adequate regulation and licensing of the profession of clinical psychology makes the potential consequences of professional ethical violations uncertain.

While some research suggests that the interpretations of ethical codes and the experience of dilemmas may be universal across cultures (10), other studies report differences depending on the cultural or sub-cultural context (11, 12) or practitioners’ personal values.

Therapists’ experiences and responses to ethical dilemmas have received some attention in research, usually in the form of practitioner surveys (13, 14, 15) and through qualitative interviews (16). These surveys highlighted that the responses of practitioners vary in terms of the degree and type of ethical dilemmas experienced as well as with regard to perspectives on appropriate resolution. The prominent dilemmas expressed were in the areas of confidentiality and concerns about the disclosure of revelations made by clients, dual relationships with clients, straddling the personal and professional domains; and concerns about the conduct of colleagues.

There is limited research on the ethical dilemmas encountered by trainee therapists in the global literature. One study selectively focused on ethical issues emerging from online trainee–client interactions (17). Indian research on the ethical issues faced by therapists in the training phase could not be found in the public domain. A pioneering Indian study (18) found that psychiatrists and psychologists in the state of Karnataka were aware of non-sexual and sexual boundary violations in practitioner–client interactions. These included socialising with or befriending clients, undue self-disclosure, accepting gifts or free services from clients, inappropriate touching, sexual talk or acts with clients. Respondents in this study expressed concerns about the implementation of professional ethics guidelines and discussed the possible role of cultural variation in the interpretation of non-sexual boundary violations. The study focused on a specific ethical domain, viz boundary violations, and covered practitioners and not trainees.

Reviews (19, 20) have highlighted the importance of awareness of and reflection on ethical practice in our country. The Right to Information Act and the Consumer Protection Act, have thrown up additional ethical quandaries for those who provide therapeutic services. Clients can use the Right to Information Act to make formal requests for documented therapy session notes from practitioners working in government organisations. While good practice suggests that therapists must document their sessions, practitioners could be uncertain about where and how much of sensitive information and their own impressions are to be documented. Client “consumers” can make complaints about perceived deficiencies in therapy services under the Consumer Protection Act. The rights should definitely be protected, but there is the accompanying danger that therapists may focus on self-protection and engage in “defensive practice” (21).

Clearly, there is a need to explore the salient ethical challenges encountered in this early phase of professional development and to find out how knowledge of professional ethics translates into action. This would have implications for training and supervision methodologies.

The present study used a qualitative lens to explore the ethical dilemmas encountered by trainee clinical psychologists and the methods they used to resolve these dilemmas.

Methodology

Aims and objectives

The study aimed to explore trainee clinical psychologists’ perspectives on the ethical dilemmas faced in the practice of therapy. The objectives were threefold: (i) to explore the types of ethical dilemmas encountered by trainee clinical psychologists, (ii) to explore the experience of ethical dilemmas in the practice of therapy among trainee clinical psychologists, and (iii) to explore clinical psychology trainees’ perceptions regarding the resolution of these dilemmas.

The study had a cross-sectional research design and used qualitative methodology.

Sample

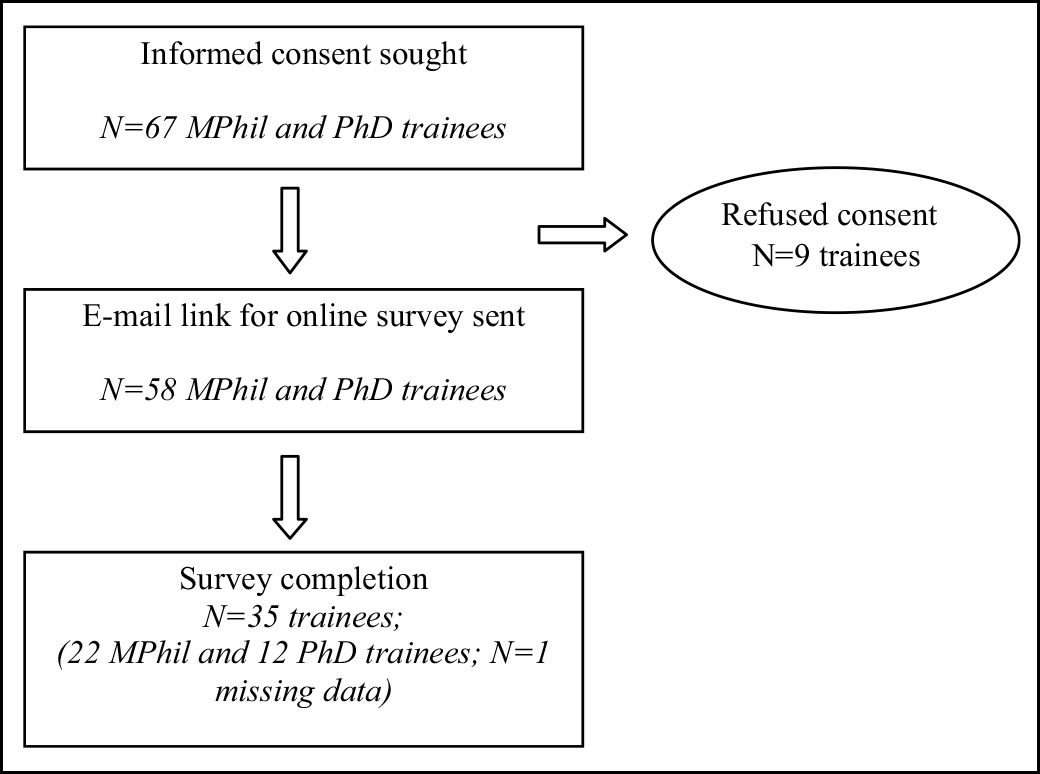

The potential sample included all 67 trainees enrolled in the MPhil or PhD programme in Clinical Psychology at a tertiary care government hospital for mental health and neurosciences in India. A total of 35 trainees, with a mean age of 27 years (SD=3.91), participated in the study. The participation rate was 52.2%.

Measures

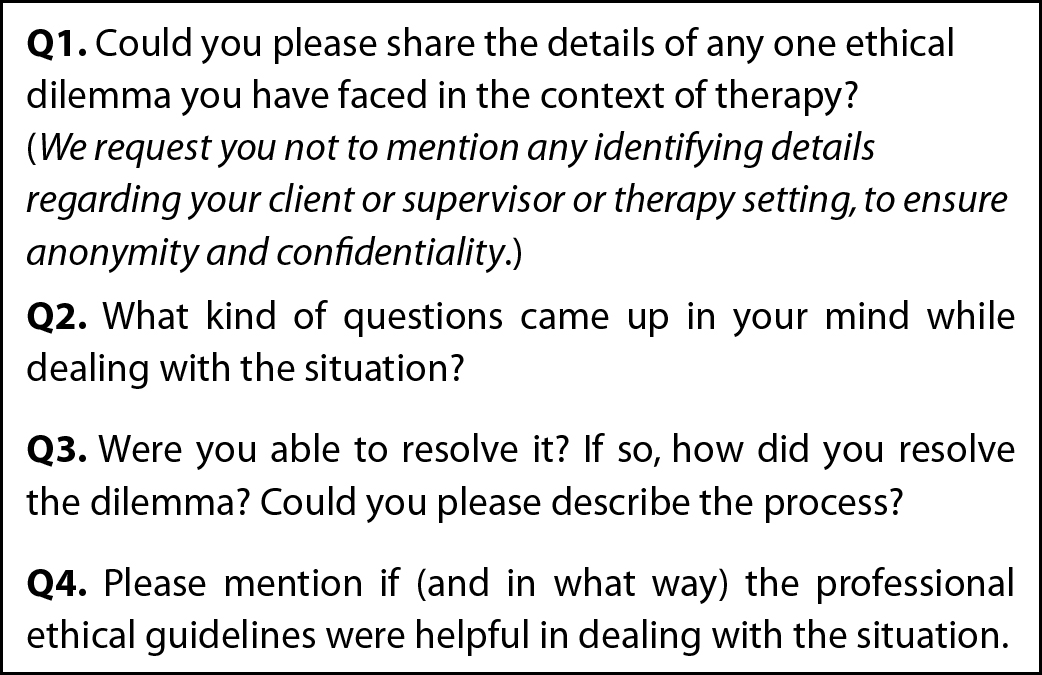

A brief survey schedule was developed for the study. It contained four open-ended questions related to a single ethical dilemma encountered by the respondent (Figure 1). The absence of any questions eliciting personal identifying details, such as gender, date of birth or year of joining the training course, ensured that anonymity was maintained.

Procedure

The study was approved by the institutional ethical review board. The survey schedule was developed on the basis of a review of the literature and was hosted online on the Survey Monkey platform. The options for SSL encryption and masking of IP addresses were enabled. There was a “no response” option for every question, and the trainees also had an option to withdraw from the survey before finally submitting their responses. Access to the online survey was password-protected and available only to the investigators of the study.

The trainees who provided written informed consent for the study were sent a secure link via e-mail to access the online survey, which was kept open for a period of three months. A generic reminder e-mail was sent to all potential participants after a period of 2–3 weeks. After the completion of the three-month period, the data were downloaded and the online survey was closed..

Analysis

Content analysis (22) of the responses was used to identify key themes or categories with respect to the main ethical dilemmas and methods of resolution. Three of the investigators examined the data independently to identify mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories with operational definitions. A consensus was reached following a discussion and the coding schedule was finalised. The frequencies and percentages of responses in each category were computed. The mean age (and standard deviation) of the respondents was calculated.

Results

The ethical dilemmas encountered by the 35 trainees in the context of therapy were coded into six categories (Table 1).

| Table 1: Types of ethical dilemmas reported by trainee clinical psychologists | ||

| Ethical dilemma category | N | % |

| Therapist–client boundaries | 13 | 37.1 |

| Confidentiality | 12 | 34.3 |

| Therapist competence | 3 | 8.5 |

| Beneficence and non-maleficence | 3 | 8.5 |

| Client autonomy | 2 | 5.7 |

| Others | 2 | 5.7 |

The most frequently reported ethical dilemma was related to the appropriate negotiation of therapist–client boundaries (37.1%). The most predominant boundary issues were related to the possibility of a dual relationship, followed by uncertainties about accepting gifts and disclosure by the therapist of details about him/herself.

The complexities of negotiating a dual relationship, as a therapist as well as a teacher–mentor to the client, are reflected in these words:

“Should I at all see her as a client, she being already a student and academic mentee? Would referring her to somebody else be good? How would she be able to pay her therapist outside campus when I know her being a student makes it financially difficult to survive? Would it not be good for me to see her when I am already aware of some of her troubles/concerns? Or would knowing them actually be a “disqualification’ for me?”

Trainees also mentioned having difficulty reconciling the pros and cons of accepting gifts from clients. For instance, “Should I take it? It’s just edible after all…if I don’t accept, will they feel rejected? If I do accept…will they think less of me and think they are close to me?”

The disclosure by the therapist of personal information or personal contact details, or revelations regarding problems similar to those of the client, were some of the major issues mentioned. One trainee described her internal dialogue thus:

“Questions such as have I unintentionally narrated the experiences? Was I supposed to avoid it? How do I avoid questions related to personal life? If I had appropriately/ inappropriately disclosed myself and to what extent one should disclose self?”

The trainee therapists found it difficult to decide the best and most ethical response when their professional role boundaries were challenged, eg when a client referred to the therapist as his/her son or asked personal questions. One trainee wondered about the limits of the professional role when a client phoned in distress late at night, and acknowledged that “they are also humans who need strength and support when alone.” Another therapist worried about the extended duration of sessions and growing closeness with a client.

One of the other prominent concerns of the trainees wasconfidentiality(34.3%). The dilemmas were related to the disclosure of certain information about clients to their family members or the legal authorities and the uncertainty regarding the limits of confidentiality. This encompassed clients’ revelations regarding sexual abuse, suicidal intent, past criminal acts or an adolescent client’s plan to run away from home without the parents’ knowledge. The therapists were confronted with competing concerns, with confidentiality on one side and the client’s safety on the other. This was compounded by the possibly negative impact on the therapeutic alliance or possible legal requirements. The process of disclosure was fraught with uncertainty. One trainee speculated, “Should it be with her knowledge or without?” Ambiguity prevailed about who should be privy to information on the client’s disclosures, or the diagnosis of mental illness or intellectual disability.

A subset of trainees (8.5%) highlighted dilemmas related to their level of competencein their role as therapists. While some felt that the workload and time pressure in the training course were impairing the quality of their work with clients, others mentioned barriers stemming from their personal values, beliefs, emotions or lack of knowledge or skill in working with specific client groups or problem areas, eg gender identity disorder, extramarital relationships or intimate partner violence. One of the trainees recounted feeling ill-equipped to deal with a case, and spoke of “dreading (my) sessions with him,” with the result that “the process came to something like a battle,” culminating in a referral to another therapist.

Around 8.5% of the trainees reported dilemmas that centred around the basic principle of beneficence and non-maleficence –the ethical imperative to benefit clients and to do them no harm. The trainees mentioned concerns about the possible negative impact of a therapeutic technique or decision on their client’s welfare. For example, one therapist had ethical misgivings about using a particular strategic therapy technique:

“Can I do something that I see clearly would worsen his condition and would be difficult to contain? Can I keep the client unaware that I expect this escalation or even that the worsening is partly planned (either before or after it has happened)?”

The trainee therapists (5.7%) also grappled with the question of whether to accept the client’s right to autonomyand self-determination while setting the goals of therapy and making life choices. These dilemmas emerged when the therapist’s values or religious beliefs were opposed to those that guided the client’s decisions and actions. For example, one trainee viewed a female client’s infidelity as morally wrong, but was simultaneously aware of a client’s right to make her own life choices and determine her personal growth.

The sixth category included two different ethical conundrums that emerged during the therapeutic process. One therapist questioned the ethical implications of defining “who is my client” when dealing with cases involving couples or a family. Another therapist spoke of the struggle arising from the ethical responsibility to respond to and report a colleague’s ethical transgressions:

“The thought that I should report it to someone senior also crossed my mind but the colleague was also one of my closest friends who had helped me and been there for me through a lot of personal difficulties in my life. I certainly did not wish to talk about it with my supervisor on the case for the fear that it would get my friend into trouble. I also wondered what I would have done in this situation had the therapist not been a friend.”

The trainee therapists experienced a range of difficult emotions when confronted with ethical dilemmas, and reported feeling pressured by a sense of responsibility, discomfort, anxiety, fear, panic, shock and irritation. The feelings of doubt and uncertainty were experienced across a range of ethical dilemmas, but were most prominently associated with the issues of competence and the appropriateness of disclosing information about oneself. The trainees reported feeling shocked when faced with unexpected ethical issues, e.g. ethical violation by a a colleague. Fear of jeopardising the therapeutic relationship or potentially harming the client was mostly reported in the context of refusing a client’s gift or breaching confidentiality. The results indicate that there was no fixed pattern of emotional response to situations; the trainees responded differently to similar ethical dilemmas. This highlights the role of individual differences and the importance of the interpretation of events. The small sample size makes it difficult to contextualise the diverse emotional experiences of the trainees.

The analysis of the responses regarding the resolution of the ethical dilemmas indicated that only 57% of the participants felt that they had resolved their dilemma successfully and effectively.

The analysis examined the frequency of the methods used by the trainees in their attempt to resolve their ethical dilemma, apart from the more private process of self-questioning and reflection (Table 2).

| Table 2: Trainee clinical psychologists’ methods of resolving ethical dilemmas | ||

| N | % | |

| Consultation and supervision | 16 | 45.7 |

| Professional ethical guidelines | 12 | 34.3 |

| Discussion with clients | 3 | 8.6 |

| Observation of professional colleagues | 1 | 2.9 |

The results indicated that supervision/consultation with peers and professional colleagues (45.7%) and guidance from ethical codes (34.3%) were the most common strategies for resolution.

The availability, accessibility and support of the supervisor were considered useful by the majority of the trainees who attempted to resolve their ethical quandary by this method. In the words of one trainee, “I think discussion with the supervisor helps. She helped me to delineate my personal values from what is professionally possible in these circumstances.”A small proportion (19%) of trainees who accessed supervision felt that this was either inadequate or unhelpful, or made the situation worse. One respondent remarked that the discussion with the supervisor resulted in “more questions than an answer to the original question.”

There were mixed perceptions of the utility of professional codes in ethically disturbing situations. About one-third of the respondents (34.3%) suggested that guidelines were informative and useful. According to one trainee, “Guidelines help the therapist not to get swayed and give in to the situation.” Among those who relied on professional ethics guidelines to resolve their dilemma, 19% commented that guidelines may have a limited role or provide partial solutions, with much of the decision-making depending on the case or context.

A large proportion of respondents (34.3%) explained why they did not turn to professional ethical codes in the face of dilemmas during therapeutic interactions with clients. Many expanded on the lack of responsiveness of the guidelines to the uniqueness or contextual aspects of each therapeutic situation. A few felt that adherence to rigid professional codes was in conflict with the value of humaneness required for relating to and working with clients. One trainee elaborated on the lack of specificity and clarity:

“Professional ethical guidelines in India…are sketchy in form, lacking elucidation. Ethical regulations given by foreign professional bodies are not culturally appropriate.”

Another method of resolution was to involve clients in the ethical debate. A small proportion of trainees (8.6%) brought the process of weighing the pros and cons of divergent responses to the dilemma directly into the therapeutic discourse. A much less common approach (2.9%) was to model one’s behaviour and choices on what was done by the majority of one’s professional colleagues in similar situations.

Discussion

Practitioners often find themselves on the “horns of a dilemma” during therapy, being faced with the prospect of making a choice between conflicting and incompatible courses of action which have good, but contradictory ethical underpinnings (23). Previous international research with practising therapists (15, 24) found that confidentiality and the negotiation of the boundaries of the relationship with clients were the most problematic domains. The findings of the present study showed a similar trend.

Confidentiality is often considered the bedrock of safe therapeutic interaction and the therapist is viewed as the “keeper of secrets” (25). While the trainee therapists were aware of their obligation in this respect, uncertainty regarding disclosure arose when their clients confided about past behaviours which contravened the law, or which related to sexual or physical abuse. The trainees also expressed a sense of conflict when it came to confidentiality in the treatment of minors, which is an area where there are no clear answers. The perspectives of the law, clinical practice and ethics intersect, and need to be negotiated, discussed and revisited in the process of therapy (26). There were other trainee therapists who were aware of their client’s right to confidentiality, but who also felt that the family’s right to know the diagnosis was important. In the Indian cultural context, the family members often accompany the client when he/she goes for treatment and feel that they must be involved and informed (27). Perhaps these cultural realities lead to uncertainty among trainees, even though the professional ethics codes are quite clear on the need to keep information about the client confidential. This study has identified a range of key areas for training in confidentiality.

There have been diverse perspectives on the sanctity and interpretation of boundaries in the therapeutic relationship. All boundary crossings, eg extending the duration of sessions and self-disclosures, may not be harmful but there is the danger of sliding down a slippery slope towards a clear boundary violation, such as sexual misconduct (28). Are we to consider boundaries as borders or fences? The dimensions of the clinical and cultural context must be considered while evaluating the ethical aspects of a therapist’s behaviour. A recent commentary (27) discussed how boundaries may be viewed differently in the Indian culture. For example, personal enquiries about the therapist might reflect typical patterns of social discourse. What then are the appropriate professional distance and emotional boundaries? De Sousa (27) outlines the need for novice therapists to be sensitive to these cultural variations and guard against too rigid or formal an approach. The implicit authority of the therapist in the “guru–chela” model of the therapist–client relationship in India (29) could influence the construction of the notion of the client’s autonomy and give rise to dilemmas. It could also make clients vulnerable to exploitative relationships that transgress boundaries. While the approach of ethical relativism respects diversity, it cannot entirely circumvent or transform the ethical guidelines formulated for the profession. Self-awareness, monitoring and discussions with the supervisor could help trainees sort out the complex questions relating to culture and ethical practice.

Issues such as accepting gifts and self-disclosure are not specifically addressed in most professional ethics codes for therapists and counsellors. These grey areas would be open to individual interpretation and trainee therapists would benefit from guided discussions and reading related professional literature (30, 31). While “cultures of gift-giving” may differ in meaning across certain western and eastern cultures, there is a danger in using this argument to justify accepting gifts from clients, without considering the meaning, implications and process of accepting or refusing a gift.

The findings of this study have implications for training in the ethical decision-making process for psychotherapists and counsellors. The trainees’ responses can be used to develop case scenarios which reflect the primary real-world concerns and pedagogy that is centred around the learner. Clearly, compartmentalised didactic instruction on professional ethical codes has limited value and may lead to “inert knowledge” (32). Tyron (33) proposed that ethical violations can be addressed by reviewing the training frameworks and evolving a range of experiential and participative methodologies. While Tyron (33) recommends that all trainees be given a copy of the professional ethical standards and sign to mark their commitment to ethical practice, this in itself would be incomplete. The larger question is how trainees will learn to critically examine the codes, reflect on the ambiguities in certain areas and translate their knowledge into practice. The integration of ethical issues across the curriculum, peer discussions in small groups and training in the ethical decision-making process (34) would strengthen training in this area.

Select responses of the trainees in this study point to the need to discuss contextual variables that have an impact on the perceptions and interpretations of ethical codes. The trainees’ comments on weighing the values of social justice and humanity against the obligation to follow “rational” principle-based ethics give rise to debates on the philosophical foundations of different ethical positions. Training programmes need to move beyond the “principle-ethics) approach’ (32), which emphasises the language of justice and universal maxims and is often seen as being embedded in western traditions. The conversation must be broadened to encompass “value ethics’ and “relational or care ethics’ (32, 35). These approaches recognise that ethical actions occur within and are influenced by relational contexts, consider the practitioner’s questions regarding “Who shall I be?” and recognise how emotions aid awareness and influence our actions.

Supervision is an important crucible for trainee therapists in the process of learning professional skills and developing their professional identity. The findings of this study confirmed the importance of guidance from an approachable supervisor when a trainee is confronted by ethical questions. The supervisory space must prioritise and legitimise the discussion of ethical issues that inevitably arise during therapeutic work. Although trainees might look for quick answers to the question, “What should I do now?”, supervisors must encourage a more nuanced exploration of the dilemma and introduce ethical decision-making models. The early phase of professional development is the opportune time to inculcate sensitivity to ethical issues; an ethical watchfulness (36) that anticipates and addresses emergent dilemmas.

In an encouraging step, the IACP has recently updated its Ethics and Code of Conduct for Clinical Psychologists. However, this information may be accessed primarily by the association’s own members and trainees may be unaware of these new guidelines, which are available online (9). As for the reporting of ethical violations by a colleague, the revised code lacks specific directions and the mechanism of accountability is still not well defined in the Indian context. The APA code was originally formulated after surveying the critical ethical dilemmas experienced by the association’s members. This method could be used to plan revisions of professional codes so that they cover the prominent dilemmas experienced by trainees and practitioners in India.

The findings of this study represent a preliminary exploration of the ethical dilemmas faced by emerging therapy practitioners. The small sample size, the purposive sampling method restricted to a single institution, and the fact that a single ethical dilemma was probed are some of the limitations of this research. There is no information on the characteristics that distinguish the group of responders from those who did not access or respond to the questionnaire. Survey or interview paradigms which include a wider array of questions could provide richer, “thicker” descriptions of the ethical dilemmas faced, their complexities and the process of resolving them. The rigour of reporting qualitative results could be enhanced by including the documentation of the researcher’s characteristics and reflexivity, as spelt out in The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (37).

This exploratory study gives us a few insights into the perspectives of clinical psychology trainees on the salient ethical dilemmas faced in the therapy room. The results may be considered signposts and could be used to identify the primary areas in which the strengthening of training in ethical paradigms and practice is required.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the assistance of Mr Siddharth Dutt, PhD scholar, Department of Clinical Psychology, NIMHANS, in the initial phase of the study.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding support: There was no funding support for the study.

References

- Kidder, R. How good people make tough choices: resolving the dilemmas of ethical living. New York, NY: Fireside Publications; 1995.

- MacKay E, O’Neill P. What creates the dilemma in ethical dilemmas? Examples from psychological practice. Ethics Behav. 1992;2(4):227-44.

- Rønnestad MH, Skovholt TM. The journey of the counselor and therapist: research findings and perspectives on professional development. J Career Dev. 2003;30(1):5-44.

- Gray LA, Ladany N, Walker JA, Ancis JR. Psychotherapy trainees’ experience of counterproductive events in supervision. J Couns Psychol. 2001;48(4):371-82.

- Skovholt TM, Rønnestad MH. Themes in therapist and counselor development. J Couns Dev. 1992;70(4):505-15.

- Orlinsky DE, Rønnestad MH. How psychotherapists develop: a study of therapeutic work and professional growth. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2005.

- Corey G, Corey MS, Callanan P. Issues and ethics in the helping professions. 4th ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing; 1999.

- American Psychological Association. [Homepage on the Internet]. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct.Washington, DC, APA; 2010. [cited 2010 Jun 1]. Available from: http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx [accessed on June 19, 2015]

- Indian Association of Clinical Psychologists (IACP) Secretariat [Internet]. Ethics and code of conduct of clinical psychologists. Guidelines 2012–13. 2014 [cited 2015 Jan 28]. Available from: http://www.iacp.in/node/159 [accessed on June 19, 2015]

- Slack CM, Wassenaar DR. Ethical dilemmas of South African clinical psychologists: international comparisons. Eur Psychol. 1999;4(3):179-86.

- Leach M, Harbin JJ. Psychological ethics codes: a comparison of twenty-four countries. Int J Psychol. 1997;32(3):181-92.

- Zhao JB, Ji JL, Tang F, Du QY, Yang XL, Yang ZZ, et al. National survey of client’s perceptions of Chinese psychotherapist practices. Ethics Behav. 2013;22(5):362-77.

- Gibson WT, Pope KS. The ethics of counseling: a national survey of certified counselors. J Couns Dev. 1993;71(3):330-6.

- Haas LJ, Malouf JL, Mayerson NH. Personal and professional characteristics as factors in psychologists’ ethical decision making. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 1988;19(1):35-41.

- Lindsay G, Clarkson P. Ethical dilemmas of psychotherapists. Psychol. 1999;12:182-85.

- Politis AN, Knowles A. Registered Australian psychologists’ responses to ethical dilemmas regarding medicare funding of their services. Aust Psychol. 2013;48(4):281-9.

- Lehavot K, Barnett JE, Powers D. Psychotherapy, professional relationships, and ethical considerations in the myspace generation. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2010;41(2):160-6.

- Kurpad S, Machado T, Galgali R. Is there an elephant in the room? Boundary violations in the doctor–patient relationship in India. Indian J Med Ethics. 2010;7(2):76-81.

- Avasthi A, Grover S. Ethical and legal issues in psychotherapy. Indian J Psychiatry: IPS Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2009:148-63.

- Isaac R. Ethics in the practice of clinical psychology. Indian J Med Ethics. 2009;6(2):69-74.

- Barnett JE. Positive ethics, risk management, and defensive practice. The Maryland Psychologist. 2007;53:30-31.

- Berelson B. Content analysis in communication research. New York, NY: Free Press; 1952.

- Kitchener KS. Intuition, critical evaluation and ethical principles: the foundation for ethical decisions in counseling psychology. Couns Psychol. 1984;12(3-4):43-55.

- Pope KS, Vetter VA. Ethical dilemmas encountered by members of the American Psychological Association: a national survey. Am Psychol. 1992;47(3):397-411.

- Trad P. The paradox of confidential communications. Am J Psychother. 1993;47(1):1-4.

- Behnke SH, Warner E. Confidentiality in the treatment of adolescents. APA Monitor Psychol. 2002;33(3):44.

- De Sousa A. Professional boundaries and psychotherapy: a review. Bangladesh Journal of Bioethics [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2015 Jan 28]; 3(2):16-26. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3329/bioethics.v3i2.11701 [accessed on June 19, 2015]

- Gutheil TG, Gabbard GO. The concept of boundaries in clinical practice: theoretical and risk-management dimensions. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(2):188-96.

- Neki J. Guru-chela relationship: The possibility of a therapeutic paradigm. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1973;43(5):755-66.

- Barnett JE. Psychotherapist self-disclosure: ethical and clinical considerations. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2011;48(4):315-22.

- Knox S. Gifts in psychotherapy: practice review and recommendations. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2008;45(1):103-10.

- Meara NM, Schmidt LD, Day JD. Principles and virtues: a foundation for ethical decisions, policies, and character. Couns Psychol. 1996;24(1):4-77.

- Tryon GS. Ethical transgressions of school psychology graduate students: a critical incidents survey. Ethics Behav. 2000;10(3):271-9.

- Pope KS, Vasquez MJ. Ethics in psychotherapy and counseling: a practical guide: 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2010.

- Jordan AE, Meara NM. Ethics and the professional practice of psychologists: the role of virtues and principles. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 1990;21(2):107-14.

- Pryor RG. Conflicting responsibilities: a case study of an ethical dilemma for psychologists working in organisations. Aust Psychol. 1989;24(2):293-305.

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245-51.