RESEARCH ARTICLE

Effectiveness of teaching medical ethics to medical students on an online platform: An analysis of students’ perceptions and feedback

Laxmi Govindraj, Samuel Santhosh, Serin Cheruvathoor Sunish, Abinaya Vannapatti Gopalakrishnan, Sujith J Chandy, Vinay Oommen, Margaret Shanthi FX

Published online first on May 20, 2022. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2022.034Abstract

Medical ethics education along with attitude and communication training has been incorporated into the regular MBBS curriculum in India from 2019, so as to encourage a caring and communicative approach by doctors towards patients. It would be important to understand the relevance of the educational module in the form of cases to ensure an optimal learning process for future students and doctors in the making. We selected three cases and conducted online debates among small groups of second year MBBS students. Students submitted narratives and their reflections after discussing each case and gave overall feedback. Our findings suggested that the students recognised the complexity of taking decisions when presented with ethical dilemmas and appreciated the opportunity to voice opposing views. The online platform was effective and may be considered in the future as a medium to help integrate discussions on medical ethics alongside clinical work.

Keywords: medical ethics, medical education, student debate, online learning

Introduction

Over the past few decades, the attitude towards doctors in India has changed from that of respect and reverence to one of suspicion and hostility. Violence and lawsuits against doctors, and doctors dying by suicide have been growing at an alarming rate [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Some of the reasons for this are poor work environment, long working hours due to inadequate resource allocation, negative perceptions about doctors among the public, and inadequate communication by doctors [5]. There are also reports of corruption and illegal dual practice by doctors in recent years, which are highlighted by the media [6, 7]. All these threaten to result in a breakdown of trust in the doctor-patient relationship, which can only be rebuilt if clinical expertise is coupled with ethical commitment and social accountability [8]. Strengthening communication and training in ethics is an intervention proposed to improve this and reduce disillusionment among both patients and doctors [5, 6].

Medical ethics education has been an integral part of the curriculum in the USA and Europe since the 1970s [9] and is now a priority in most countries [10, 11]. In addition to the “hidden curriculum” that was traditionally expected to impart ethics to a medical student, there is consensus that formal training as part of the regular medical curriculum is desirable. In keeping with this, the Medical Council of India (MCI), [now, the National Medical Commission (NMC)], has reformed its approach to medical education by introducing competency-based education and Attitude, Ethics and Communication (AETCOM) training [12] in the medical undergraduate curriculum in India since 2019. An AETCOM module [12] designed by the MCI for this purpose divides ethics training into chapters to be imparted throughout the years of medical training. This step is commendable and would introduce the concept of ethics and the importance of communication before forming habits during early patient contact. However, even in countries with a regular ethics programme, there is no gold standard for pedagogical methods or evaluation strategy, and concerns remain that the discipline is covered sub-optimally [13, 14, 15, 16]. The need of the hour is, therefore, to identify an optimal approach for medical students to apply their minds to ethical issues and practice good communication with their patients. The AETCOM module may fill this need. However, it would be important to explore the students’ perceptions and attitude while participating in the AETCOM module so that the outcome with students can be optimised.

Towards determining this, an exercise was conducted with medical students in the second year of MBBS to study their perceptions and attitude towards discussing AETCOM through paper cases as part of the regular curriculum. In the face of the Covid-19 pandemic and the national lockdown, there was no scope for a face-to-face discussion and hence, the entire exercise was done virtually. An additional challenge therefore arose to find whether online platforms were effective media to conduct in-depth group discussions. Our objectives, therefore, were to evaluate the effectiveness of teaching AETCOM to students in the second year of MBBS through small group discussions over an online platform, and evaluate the satisfaction among both students and faculty of such an exercise.

Materials and Methods

Study designThis cross-sectional study was carried out among the entire batch of 99 students of second year MBBS.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Christian Medical College, Vellore. As it was part of the regular academic activities for the batch and no personal information was collected, the IRB permitted a waiver of consent.

Cases and preparationTo initiate the preparations for this study, a discussion was held among faculty members and three cases from the MCI AETCOM module [12] were chosen.

The first case was one where a patient’s husband asks the doctor to hide the fact that the patient has lymphoma and instead inform her that she has tuberculosis. The second one was a scenario where a doctor in a busy outpatient department (OPD), administers an injection to a child which he believes was a vaccine but turns out to be gentamicin, an antibiotic, which was loaded for the treatment of another patient by the nurse on duty. The third case described a pharmaceutical company representative sponsoring a trip to Singapore for a doctor and his family to attend a seminar at the launch of their new drug in return for promoting it.

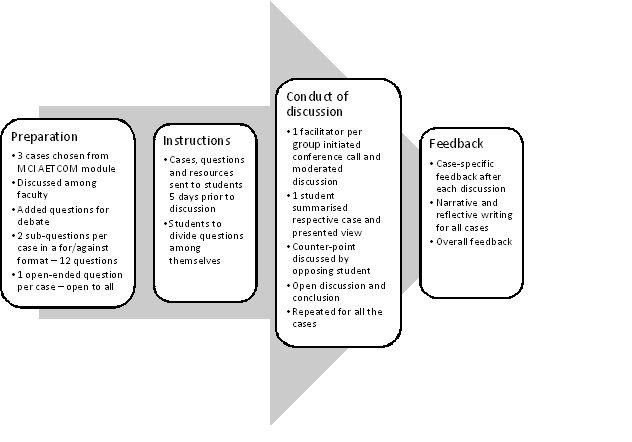

In order to ensure a distributive participation and contribution from all students, sub-questions were additionally formulated based on the points mentioned in the module [Figure 1]. Each of these was then framed into a debate format for the students to put forward opposing viewpoints during the discussion. The cases, questions, and the group division were sent to the students five days prior to the discussion, along with resource material such as the Medical Council of India Regulations, 2002 and the Uniform Code of Pharmaceuticals Marketing Practices (UCPMP) so that students could do preparatory reading and critically think through the cases. [17, 18].

Figure 1: Flowchart on methodology of online discussion

On the day of the exercise, the discussion was carried out on an online platform over three hours in nine groups of 11 students each with a faculty moderator in each group. Feedback on the content of each discussion was collected as a case evaluation at the end of each case discussion. An overall “end-of-session feedback” was also collected from students and faculty by means of online forms containing both closed questions to be graded on a Likert scale as well as two open-ended questions. In addition, students were instructed to submit a written narrative on all three cases after the discussion and include their reflections on the same.

Compilation of feedback and analysisFeedback given by the students and faculty were transferred to an MS Excel sheet. Feedback collected after each discussion as an evaluation of the case was expressed as proportions. For the end-of-session feedback, responses collected on a Likert scale were expressed as proportions for each category, and median scores were calculated for the same. Open-ended feedback on “what was good about the session” (positive comments) and “what could be improved” (suggestions and drawbacks) were included in these forms. This feedback was analysed manually and responses grouped together when they had the same underlying meaning. These groups were labelled based on the most frequent phrases appearing in the feedback for each and summarised as proportions. Students’ views were included verbatim in a separate table when they highlighted key aspects within these groups. In addition to the structured feedback, students shared their reflections on the cases through narrative writing and these responses were submitted electronically to their respective moderators. These were read and graded manually by the moderators. Those which contained substantial reflections were sent to the investigators. Wherever these reflections added clarity to the case-evaluation feedback by way of illustrating the students’ interpretation of each case, or how the exercise influenced their views, such quotes were included in the findings and discussion.

Results and discussion

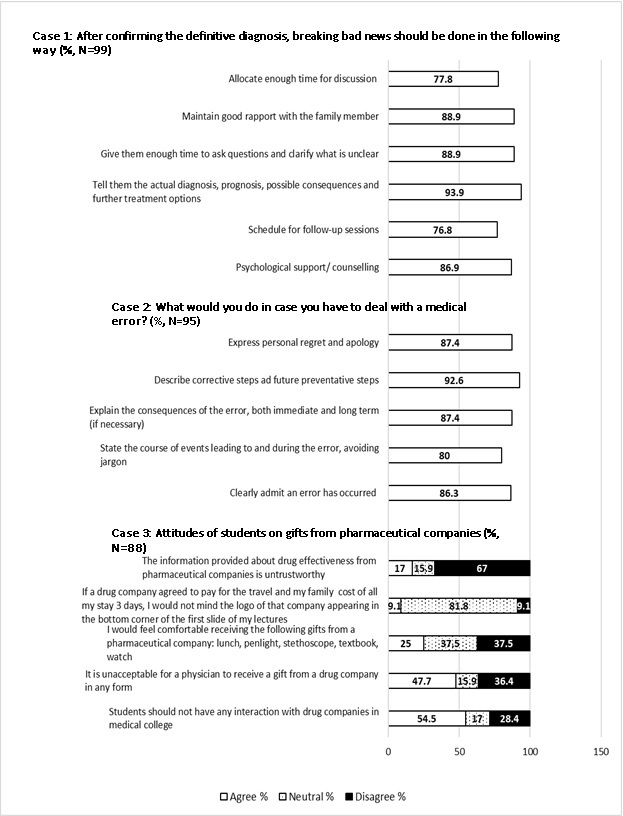

Ninety-nine students and 9 faculty took part in the exercise which was held over a three-hour session. All 99 students submitted their feedback and reflections on the discussion, either typed or handwritten, and scanned. For the case-specific evaluation, the response rate was 100% for the first case, 96% for the second and 88.9% for the third case [Figure 2]. We present a case-by-case summary of the reflections and narratives submitted by the students followed by an analysis of the focussed feedback. The feasibility of the teaching-learning method and the web-based platform is discussed at the end.

Figure 2: End of discussion evaluation for cases

The second year of MBBS is considered a good time to devote learning hours for medical ethics as students have some bedside experience and are exposed to different professionals, clinical scenarios, and patients from different strata of society [11]. It is also the first time that patient-doctor interactions are being observed by the students which facilitates impressions and later habits, when the students themselves become doctors. Discussion of various scenarios is a simple way to incorporate the subject of ethics in the regular course of study.

Case 1The first case was on full disclosure of the details of the diagnosis to a patient and their right to be fully informed about their illness. Students were firm that a patient whose mental state was normal should enjoy full autonomy. Seventy-seven (77.8%) students strongly felt the need for discussing the diagnosis with a patient, and 93 (93.9%) supported full disclosure of the diagnosis and giving the patient the opportunity for making an informed decision [Figure 2]. The opposite view was also recognised:

“At first I felt it was wrong and that the patient has the right to know everything that he/she is diagnosed with, but I was allotted (to argue in the opposing group) against this and researched upon it. I realised that there are exceptions to this too”.

Students appreciated the complexity of making a judgement call — whether to respect a spouse’s concern for the emotional health of a patient or look solely at a patient’s rights. They also brought out the concept of therapeutic privilege and non-maleficence with respect to psychological health. Some reflected on similar situations that they had already encountered:

“I realised that sometimes it’s ok to not overburden an 85-year-old with a gruesome diagnosis and instead let her live her last days in peaceful ignorant bliss.”

A question was added to the original case on whether details of a disease can be withheld from family members. There was consensus that the wishes of a patient should be respected.

In an Indian setting, where the family is still instrumental in caring for a patient, the discussion also highlighted the importance of avoiding stigma while ensuring a strong support system physically, emotionally and financially. The importance of full disclosure of the diagnosis and details of treatment when taking informed consent was also touched upon.

The disclosure of life-changing diagnoses like malignancy is sensitive, both among doctors and patients. The questions of how, when and how much to tell a patient about their cancer is an ethical dilemma which may never be fully resolved [19]. Despite it being widely accepted and considered ethically appropriate that the patient has a right to know his/her full diagnosis, the subject may not be black and white. Ghoshal et al did a survey of patients’ and families’ attitudes to the full disclosure of a cancer diagnosis in a tertiary cancer hospital in India and found these to be contrasting [20]. Kazdaglis et al address this question in the light of different cultures and found that while an oncologist in the USA, England, Canada or Finland would reveal all the details of the diagnosis to the patient, one in Japan, Greece or the Middle-Eastern countries may speak to the family and respect their opinion regarding disclosure to the patient [19]. The need for a personalised approach to each patient remains of paramount importance and a doctor may best be guided by the awareness that the diagnosis transforms the patient’s life [21].

Case 2The second case was on disclosure of medical errors and was quoted by the students as being “more relatable”. Of the 95 students who responded, 82 (86.3%) were sure that they needed to clearly admit and apologise in case an error occurs during the treatment of a patient [Figure 2]. The students’ narratives addressed the importance of honesty and trust that is built in a doctor-patient relationship and felt that non-admission of an error was a betrayal of this trust. The courage and mental strength that goes into admitting any error was also appreciated by them, going as far as to admit that their first reaction would not be to report the error, though they knew it was the right thing to do. The significance of reporting errors was also stressed.

“No matter how serious the mistake was, it is necessary to report the error to the appropriate authorities who can help us and also to audit such incidents (and) prevent such events in the future.”

Students were also aware of the legal angle and practical issues:

“Every incident should be reported because the hospital if big and trustworthy will definitely step up to help its doctors if the patient party sues”.

The final verdict in all the narratives reflected the importance of preventing errors by proper labelling of medications, cross-checking at every level of patient care, proper communication, and documentation. There was also a discussion on medical negligence and the students observed that an accident like the one in this case, is not equivalent to negligence [22].

The students’ view on reporting errors to authorities reflected not only the awareness of legal action a doctor may face, but also an understanding of the real-world situation, where the hospital may not always support a doctor who commits an error. There is no law addressing medical errors, and hospitals usually encourage reporting errors as a part of quality assurance [23]. Hébert et al, in their series of papers on bioethics, devote a chapter to disclosure of medical errors [23]. They address, in detail, the need for admitting an error, the practical difficulty in doing so and suggestions on how to deal with a situation involving an error. Since not every error is preventable, it is important that students and doctors are trained early on to accept that human imperfection cannot always be avoided, no matter how high standards they set for themselves [23].

Case 3This case highlights the value of integrity, specifically on accepting gifts from the pharmaceutical industry in return for prescribing their products. It is a common allegation that doctors conspire with pharmaceutical companies [24]. In this example, a doctor is offered an all-expenses paid trip to Singapore with family to a product launch as “a way of saying thank you for all the support in the past and the support that you are going to provide in making this new molecule a success”.

Students read the related regulations: Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) Regulations, 2002 [17]; Uniform Code of Pharmaceutical Marketing Practices, Government of India, 2014 [18] and presented their views. Seventy-two students (82%) declared that they would not compromise on their values and display the logo of a pharmaceutical company on their slides in exchange for alluring gifts [Figure 2]. Narratives submitted by the students suggested the danger of accepting gifts:

“… it could lead to unwanted obligation on the part of the doctor to prescribe that particular drug irrespective of whether it is the right choice”.

The conclusion of the case discussion was that only scientific reasons should govern the choice of a medication and it should be in the “best interests of the patients”. The point was raised that indirectly, it is the patient who pays for any gifts a doctor accepts. There was also a discussion on the handling of free samples and the rules that govern this in our country [17, 18]. However, the reflections of the students showed some indecisiveness at the end of the session. Of the 88 students who submitted feedback, only 42 (47.7%) were firm that accepting any form of gift was unacceptable and 22 (25.0%) declared that they personally would accept “smaller” gifts [Figure 2]. The varying views that were expressed through this exercise will help the faculty to identify areas which need to be strengthened in both the curriculum and also in the real-life approach by future doctors. The dynamics and limits of the doctor-industry relationship [17] should be clear in the students’ minds, so that it does not influence their objectivity in decisions taken as doctors in the future.

An open-ended question on whether pharmaceutical companies may be permitted to conduct clinical trials was also added to raise awareness of this fact. Students were unaware of the fact that a large proportion of clinical trials were initiated and carried out by the pharmaceutical industry. The importance of informed consent, voluntary participation and regulatory approval were brought out:

“It was concluded (after the discussion) that conducting drug trials is very costly and that it is ethical for pharmaceutical companies to sponsor drug trials provided that the trials are reviewed by an independent ethical review board”.

The fact that students were poorly informed about a doctor’s potential association with the industry, highlights the importance of such discussions. Lanier, in an editorial for Mayo Clinical Proceedings [25], discusses the historical discoveries in pharmacology including cortisone, cimetidine, propranolol and azathioprine as fruits of successful doctor-industry collaborations in contrast to industry-sponsored research today. Students should also be exposed to both sides and strive to maintain neutrality while collaborating with the industry as part of research [26]. They should also be aware of the concept and scope of conflicts of interest while reviewing medical literature [26]. AETCOM sessions are an optimal platform to discuss the doctor-pharmaceutical industry relationship and debate on the risks and benefits. This aspect of ethics will have to be reinforced on a periodic basis when the students have direct exposure to the industry and its representatives.

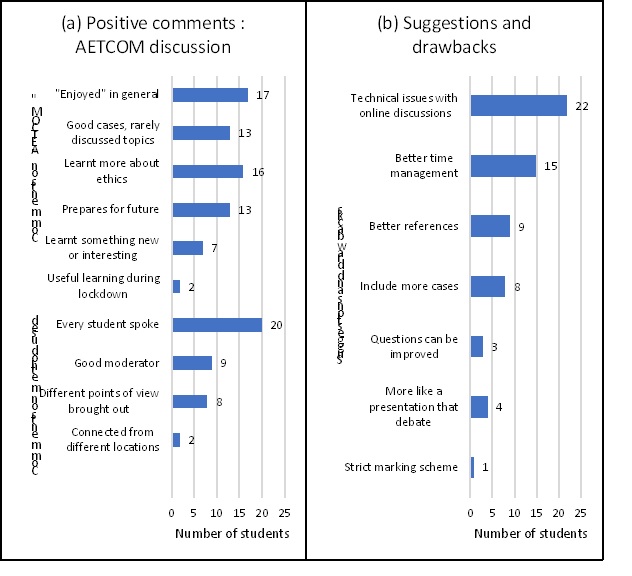

Summary of feedback about the exerciseFigure 2 shows the end-of-discussion evaluation for the three cases. More than 85% of the students agreed that such sessions helped them build better attitude and empathy towards patients and reduce violence against doctors. The students supported formal training in ethics and communication [Figure 4, available online only]. Though only 25 (25.0%) of the students had thought of more than 90% of the issues addressed during the session, 70 (70.7%) were familiar with more than half of them. Figure 3(a, b) show the group-wise proportions for the free-text feedback given by the students and Supplementary file 1 (available online only) shows some quotes taken verbatim from this feedback. In their feedback, all the faculty agreed that the students appreciated the ethical aspects in the cases discussed and respected each other’s viewpoints during the session. The experience was described as enjoyable, and there was a feeling of commitment to learning with the students. Four of the faculty (44.4%) (said they would choose to take part in the activity again given a chance.

Figure 3 (a,b): Summary of free text feedback: (a) Positive comments in feedback (N=99,100%) (b) Suggestions and drawbacks (N=62, 62.6%)*

* Some students gave more than 1 positive comment, and not all students gave suggestions

Knowledge is different from practice, especially in ethics, where knowledge of ethical principles need not ensure ethical behaviour [27]. Though both educators and students agree that medical ethics should be a part of the regular medical curriculum, the attendance and engagement in discussions on medical ethics are on the lower side. Liu et al discuss in detail the disconnect between the value placed on ethics education and the poor response to courses on medical ethics, and address the complexity in designing and effectively implementing medical ethics curricula [14]. Different teaching-learning methods suggested for teaching of ethics include large and small groups, case-based, reflective writing, brainstorming, video cases and role modelling [9, 11, 14, 28]. Lectures supplemented by role plays and video demonstrations have been implemented for first year medical students in India and the results have been published [29, 30]. Programmes have also shown good results when the facilitators were students from the immediate senior batch, “near-peer facilitators” [31, 32]. Standardised patients are also a good way to introduce and debate on ethics [11, 33].

A small group setting was accepted across studies on ethics training [10, 11, 14, 15]. Saltzburg [11] also emphasises the need for reflection on real-life experiences and integration into the clinical setting and not a structured ethics training alone. This has been found to enhance psychological and moral growth [11]. Small group sessions ensure a continuous discussion with the possibility to argue points and bring out more angles to approach a situation. Our method was similar to that used by Tysinger et al [34]. The discussion, however, was conducted in a debate format, and students were asked to individually submit narratives and reflections on the cases. In this way, it was possible to include every student in the discussion, and judge how much each person was able to imbibe during the discussion. It also prompted the students to explore two opposite approaches to the case in question. The conduct of the discussion in this manner was appreciated, especially the opportunity for everyone to speak. Students also appreciated the different viewpoints which is crucial to a discussion on ethics. Faculty also responded positively and were in full agreement that the discussion was well conducted, with the students showing mutual respect and an appreciation for adherence to ethics in the cases discussed.

Faculty training is emphasised by the MCI [35]. Nine (9.1%) of our students, in their open-ended feedback, emphasised that the role of the moderator was important. While teaching applied ethics, one should not only teach the principles or subject matter but also create an environment where there is reinforcement of a student’s inherent good qualities [27]. It is also important to deal more with ethical issues encountered in daily doctor-patient interactions rather than headline-making encounters [27]. Hence, ethics may be taught by and learnt from various teachers, who are not only experts in medico-legal issues but also bioethicists or medical teacher in the clinics. This has been discussed in detail by Glick [27]. It is sometimes argued that the aim of ethics education should focus on providing future physicians with skills to handle ethical dilemmas, rather than to create moral physicians [16]. Our students, nevertheless, highlighted the fact that guidance is important in learning and discussing ethics.

Online platforms for small group discussions: do they work?Since the lockdown precluded traditional classroom learning, we were forced to conduct a purely online discussion. It was apparent from analysing the feedback and narratives submitted by the students that the discussion was fruitful [Figures 2, 3a, 3b]. Twenty-two (22.2%) students were affected by technical issues and a few mentioned their preference for face-to-face discussions. Two percent of students specifically expressed their satisfaction at being able to have such an exhaustive discussion remotely, from across the country [Figures 3a, b]. Although we did not find studies that described purely online discussions, Lipman et al [36] studied whether there was any added advantage of internet-based teaching of ethics in sophomore* year medical students. They found that the group wherein internet-based discussion was added to the classroom discussion performed significantly better on external evaluation. Thus, internet-based learning and remote communication are effective in discussion of ethics. Such tools can be used in regular training as well, when physical distance would be a barrier for discussion.

Limitations

Our exercise was limited to the second-year medical students with no follow up. A follow-up study may be planned for a later date, once the students have been exposed to ethical issues in the clinics, to evaluate how training in ethics contributed to their decision making. A pre-session questionnaire would have enabled measuring the change in the students’ attitude about learning medical ethics before and after the session.

Conclusion

There is increasing dissatisfaction among doctors and violence against the medical community. Possible contributing factors for this could be sub-optimal attitude, ethics and communication within the doctor-patient relationship. It is therefore important to address the affective domain of the medical professional through the teaching of applied ethics through modules such as described here. This would help sustain interest in work, values, empathy and an appreciation for patient and community interaction [37].

Our online discussion-cum-debate on ethics, attitude and good communication based on the AETCOM module of MCI saw enthusiastic participation from students and faculty. The feedback received for this activity suggested that small group discussion was effective even over a web-based interactive platform. There was unanimous student support for the initiative to incorporate ethics and communication training into the regular curriculum for MBBS as an AETCOM module. The importance of autonomy, full disclosure of diagnoses as well as errors, and the various dimensions of the doctor-pharmaceutical industry relationship were brought out by the students effectively, despite the exercise being conducted remotely. Both students and faculty through their feedback expressed satisfaction on the conduct of the discussion and their willingness to partake in a similar activity in the future.

Thus, even after classrooms reopen, online sessions can facilitate bringing together medical students to discuss specific ethical and communication issues encountered in the wards without having to be in the same physical space. Virtual discussions can thus contribute to integrating ethics with the regular subjects during the clinical years of the medical course as well. Having such virtual exercises on ethical issues would enable the discussion of observed issues when they are fresh in the students’ minds and promote inculcation of ethics into day-to-day practice of the future professional.

*Note: Sophomore — (in the United States of America) is a student in the second year of college or high school.

Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge our colleagues Prof. Jacob Peedicayil and Dr K.P. Kiruthika for their suggestions on the manuscript. We would also like to thank the batch of 2018 MBBS and all the faculty of the Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, for their active participation in the activity.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Statement of similar work: This paper contains original research and has not been submitted / published earlier in any journal and is not being considered for publication elsewhere.

References

- Nagpal N. Incidents of violence against doctors in India: Can these be prevented? Natl Med J India India. 2017 Mar-Apr;30(2):97–100.

- Dora SSK, Batool H, Nishu RI, Hamid P. Workplace Violence Against Doctors in India: A Traditional Review. Cureus. 2020 Jun 20 [cited 2020 Dec 7];12(6):e8706. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8706

- Akhter S. Patients are now suing doctors at an alarming rate: Mahendrakumar Bajpai. ETHealthWorld. 2016 Mar 16 [cited 2020 Dec 7]. Available from: http://health.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/industry/patients-are-now-suing-doctors-at-an-alarming-rate-mahendrakumar-bajpai/51420266

- Perappadan BS. Majority of doctors in India fear violence, says IMA survey. The Hindu. 2017 Jul 2 [cited 2020 Dec 7]. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/health/majority-of-doctors-in-india-fear-violence-says-ima-survey/article19198919.ece

- Reddy IR, Ukrani J, Indla V, Ukrani V. Violence against doctors: A viral epidemic? Indian J Psychiatry. 2019 Apr;61(Suppl 4):S782–5.

- Kane S, Calnan M. Erosion of Trust in the Medical Profession in India: Time for Doctors to Act. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016 Nov 2;6(1):5–8.

- Khan SA. An unhealthy statement. The Indian Express. 2018 May 3 [cited 2022 Apr 8]; Available from: https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/an-unhealthy-statement-narendra-modi-london-indian-doctors-5160669/

- Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet. 2010 Dec 4;376(9756):1923–58.

- Lehrmann JA, Hoop J, Hammond KG, Roberts LW. Medical Students’ Affirmation of Ethics Education. Acad Psychiatry. 2009 Nov 1;33(6):470–7.

- DeFoor MT, Chung Y, Zadinsky JK, Dowling J, Sams RW. An interprofessional cohort analysis of student interest in medical ethics education: a survey-based quantitative study. BMC Med Ethics. 2020 Dec;21(1):26.

- Saltzburg L. Is the current state of medical ethics education having an impact on medical students? Online J Health Ethics. 2014 Jan 1 [cited 2020 Sep 7];10(2). Available from: http://aquila.usm.edu/ojhe/vol10/iss2/2

- Medical Council of India. Attitude, Ethics and Communication (AETCOM): Competencies for the Indian Medical Graduate. 2018.

- Fawzi MM. Medical ethics educational improvement, is it needed or not?! Survey for the assessment of the needed form, methods and topics of medical ethics teaching course amongst the final years medical students Faculty of Medicine Ain Shams University (ASU), Cairo, Egypt 2010. J Forensic Leg Med. 2011 Jul;18(5):204–7.

- Liu Y, Erath A, Salwi S, Sherry A, Mitchell MB. Alignment of Ethics Curricula in Medical Education: A Student Perspective. Teach Learn Med. 2020 May 26;32(3):345–51.

- Mattick K, Bligh J. Teaching and assessing medical ethics: where are we now? J Med Ethics. 2006 Mar;32(3):181–5.

- Miles SH, Lane LW, Bickel J, Walker RM, Cassel CK. Medical ethics education: coming of age. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 1989 Dec;64(12):705–14.

- Medical Council of India. INDIAN MEDICAL COUNCIL (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) Regulations, 2002. Part III, Section 4 of the Gazette of India; 2002 April 6. [cited 2020 Nov 11]. Available from: http://wbconsumers.gov.in/writereaddata/ACT%20&%20RULES/Relevant%20Act%20&%20Rules/Code%20of%20Medical%20Ethics%20Regulations.pdf

- Govt of India. Uniform Code of Pharmaceuticals Marketing Practices (UCPMP) -. 2014 Dec 12: 1-14 Available from: https://pharmaceuticals.gov.in/sites/default/files/Uniform%20Code%20of%20Pharmaceuticals.pdf

- Kazdaglis GA, Arnaoutoglou C, Karypidis D, Memekidou G, Spanos G, Papadopoulos O. Disclosing the truth to terminal cancer patients: a discussion of ethical and cultural issues. East Mediterr Health J. 2010 Apr 1;16(4):442–7.

- Ghoshal A, Salins N, Damani A, Chowdhury J, Chitre A, Muckaden MA, et al. To Tell or Not to Tell: Exploring the Preferences and Attitudes of Patients and Family Caregivers on Disclosure of a Cancer-Related Diagnosis and Prognosis. J Glob Oncol. 2019 Nov;5:1–12.

- Jutel A. Truth and lies: Disclosure and the power of diagnosis. Soc Sci Med. 2016 Sep 1;165:92–8.

- The Association of Surgeons of India. Medical Negligence – The Judicial Approach by Indian Courts –. [cited 2020 Nov 11]. Available from: https://asiindia.org/medical-negligence-the-judicial-approach-by-indian-courts/

- Hébert PC, Levin AV, Robertson G. Bioethics for clinicians: 23. Disclosure of medical error. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J. 2001 Feb 20;164(4):509–13.

- PM must prove his charge or apologise: IMA. The Hindu . 2020 Jan 15 [cited 2021 Jan 12]; Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/pm-must-prove-his-charge-or-apologise-ima/article30569676.ece

- Lanier WL. Bidirectional Conflicts of Interest Involving Industry and Medical Journals: Who Will Champion Integrity? Mayo Clin Proc. 2009 Sep;84(9):771–5.

- Ehrhardt S, Appel LJ, Meinert CL. Trends in National Institutes of Health Funding for Clinical Trials Registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. JAMA. 2015 Dec 15;314(23):2566.

- Glick SM. The teaching of medical ethics to medical students. J Med Ethics. 1994 Dec;20(4):239–43

- Mahajan R, Aruldhas BW, Sharma M, Badyal DK, Singh T. Professionalism and ethics: A proposed curriculum for undergraduates. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2016;6(3):157–63.

- Srabani Bhattacharya, Sundaram Kartikeyan. Experiences with AETCOM module training for first-year MBBS students. Int J Sci Res. 2020 Jun;9(6).

- M. Vijayasree. Perception of Attitude, Ethics and Communication Skills (AETCOM) Module by First MBBS Students as a Learning Tool in the Foundation Course. J Evid Based Med Healthc. 2019 Oct 16;6(42):2750–3.

- Sullivan BT, DeFoor MT, Hwang B, Flowers WJ, Strong W. A Novel Peer-Directed Curriculum to Enhance Medical Ethics Training for Medical Students: A Single-Institution Experience. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020 Jan 1;1-10

- 32. DeFoor MT, East L, Mann PC, Nichols CA. Implementation and evaluation of a near-peer-facilitated medical ethics curriculum for first-year medical students: a pilot study. Med Sci Educ. 2020 Mar 1;30(1):219–25.

- Stites SD, Clapp J, Gallagher S, Fiester A. Moving beyond the theoretical: Medical students’ desire for practical, role-specific ethics training. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2018 Jul 3;9(3):154–63.

- Tysinger JW, Klonis LK, Sadler JZ, Wagner JM. Teaching ethics using small-group, problem-based learning. J Med Ethics. 1997 Oct;23(5):315–8.

- Zayapragassarazan Z, Kumar S, Kadambari D. Record Review of Feedback of Participants on Attitude, Ethics and Communication Module (AETCOM) proposed by Medical Council of India (MCI). Educ Med J. 2019 Mar 29;11(1):43–8.

- Lipman AJ, Sade RM, Glotzbach AL, Lancaster CJ, Marshall MF. The incremental value of internet-based instruction as an adjunct to classroom instruction: a prospective randomized study. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2001 Oct;76(10):1060–4.

- Mitra J, Saha I. Attitude and communication module in medical curriculum: Rationality and challenges. Indian J Public Health. 2016;60(2):95.