HISTORY

COMMENTARY: Archives, mental health systems, and the history of mental health in colonial South India: Critical questions

Sathya D, Sudarshan R Kottai

Published online first on December 6, 2025. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2025.092Abstract

Emerging trends in the history of mental health globally emphasise the need to critically examine the history of mental health, and this applies to colonial India as well. However, despite the inseparable relationship between social hierarchies (such as race and caste) and mental health outcomes, we find that archival sources on mental health in colonial South India remain inaccessible, limiting researchers’ ability to understand the complexities and nuances of this relationship. Despite an extensive search through state archives, records of mental health institutions, and other government departments, anticipated sources remain elusive. We argue that mainstream mental health systems exhibit a lack of sensitivity to the socio-historical roots of mental health crises and are plagued by systemic issues, such as staff shortages and limited access to sources, which contribute to a poor understanding of marginalised peoples’ experiences. Mental health systems need to deepen their awareness of the socio-historical determinants of human suffering. This is vital to realising an ethical, people-centred mental healthcare ecosystem.

Keywords: history, mental health, famine, cultural competence, archives, mental health ethics

Why history for (mental health) ethics?

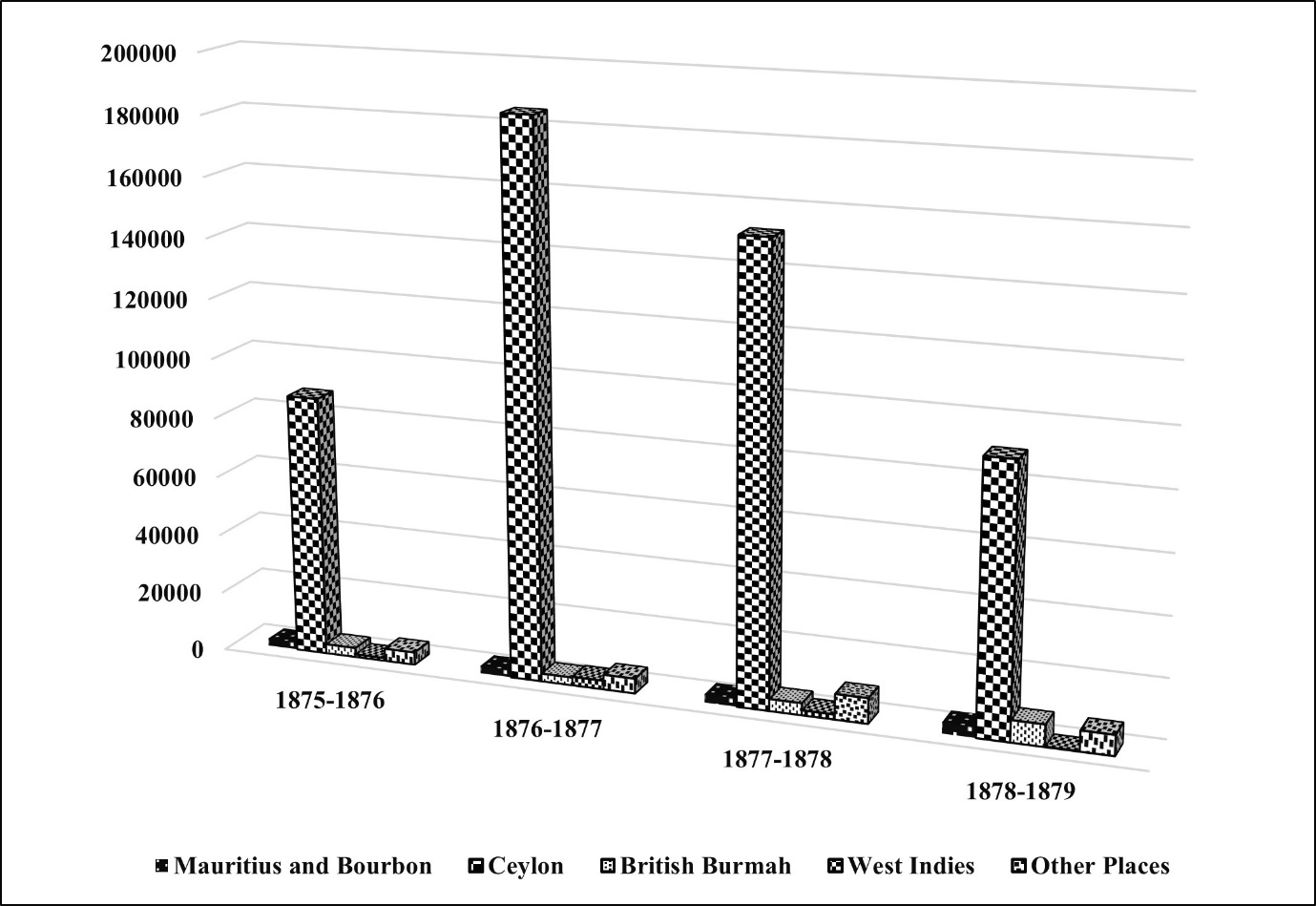

On February 16, 2024, Yale University publicly apologised for its historical ties to slavery, including the use of enslaved labour for the construction of campus buildings. Notably, individuals affected by the Madras famine (1686) were enslaved, transported, and forced to labour on construction works [1, 2]. Colonial rule in India was a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, with famines having a profound and lasting impact. Thus, one could argue that they would have had a lasting impact on the mental health of affected populations, perhaps for multiple generations. This link between historical events and mental health is evidenced by research on marginalised populations in other regions. Mental health research from the Caribbean region claims that there is a higher rate of suicide among the Indian descendants of indentured labourersa compared to other immigrant groups (colonial famines drove mass migration. Figure 1 shows that during the great famine of 1876-1878, there was a mass migration from Madras Presidency to other parts of the world) [3]. A study conducted in Guyana shows that cultural pressures within the Indian communities are linked to high suicide rates, eg, rigid social norms and conflict between traditional and modern moral values among Indo-Guyanese families often led to death by suicide among youths [4].

Figure 1. Emigration from Madras Presidency to other countries between 1875 and 1879 (Source: Report on the Administration of the Madras Presidency during the year 1877-1878. Madras: Govt. Press. 1879. 279 p.)

History and culture potentially influence mental health. However, in mainstream mental health settings, the meaning of “history” is almost always limited to clinical history, often restricted to individual signs and symptoms. It is vital to move beyond these to account for a person’s history, which is shaped by generations of experience. For example, Carrasco et al found that the discrimination and dispossession of an indigenous community in La Soledad, Mexico, was the fundamental cause of chronic childhood malnutrition, making conventional modes of intervention — like creating awareness about nutrition — futile [5]. Kleinman et al remind us that even though trauma, pain, and disorders seem like medical problems, they may be rooted in larger political issues and social pathology that deleteriously impact individual mental health [6].

Without paying attention to the indigenous cultural resources, mental health professionals tend to commit violence by reframing social suffering as psychiatric problems to be treated with individualised approaches like psychopharmaceuticals. Hence, being sensitive to an individual’s culture and respecting individual rights and dignity is a fundamental, ethical mandate for a psychologist [7]. According to Kirmayer, cultural competence is a clinical skill that “aims to make healthcare services more accessible, acceptable and effective for people from diverse ethnocultural communities” [8: p151]. Thus, a rigorous historical consciousness is imperative for establishing socio-cultural competence and an ethical mental healthcare practice.

The colonial past, present, and future of mental health

Critical mental health studies on the historical impact of structural violence, such as racism, sexism, communal violence, poverty, war, and social injustice, are invaluable in advancing knowledge on mental health ethics [9]. Before India’s Independence, the Bhore Committee (1946) reported that most mental hospitals in the country were understaffed, inefficient, notorious places of custody rather than of healing [10]. The report highlighted the dire state of “lunatic asylums”b under colonial rule; however, even after 75 years of Independence, the history of mental health in colonial South India remains under-researched. Numerous global events since the nineteenth century have compelled us to closely observe socio-political events to understand their impact on mental health. For example, during the Partition of India, forced migration, displacement, loss of kith and kin, the struggle for survival, and gendered violence caused mental distress [11]. Two decades of political unrest in Sri Lanka accelerated mental distress among Sri Lankan Tamil refugees. The brutal killing of family members, rape, and devastation gutted the mental health of these communities. Rape survivors from Sri Lanka suffered from anger, fear, loss of confidence, and hypervigilance [12]. The women survivors of the Bhopal gas tragedy suffered from social distress; young women remained unmarried since it was assumed that they could not bear children [13]. Following the 2001 Bhuj earthquake, 75% of teachers and 100% of school students suffered from mental health–related crises [14]. The ongoing Russia–Ukraine and Israel–Palestine wars are stark reminders of the political determinants of mental health. The bombing of health centres in Gaza, mass displacement, widespread loss of life, and the inability to grieve deeply impact mental health [15]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 9.6 million people are at risk of mental health crises in war-torn Ukraine [16]. Hence, historical episodes, particularly those related to national and transnational conflicts, have significant effects on the mental health of not just individuals but populations, with the potential for intergenerational repercussions.

Thus, we argue that understanding the socio-cultural and political context of suffering is a crucial competency for mental health professionals. Empathy for an individual’s personhood, and respect for varied belief systems and cultural values, are significant ethical considerations when deciding if a problem needs to be viewed as merely an individual mental health problem. Investigating the historical context of mental health helps historicise and thus re-politicise mental health, thus enabling the formulation of interventions that account for past injustices and resist current inequalities, power relations, and hierarchies [17]. For such historical studies, particularly concerning colonial history, it is essential to examine archival material and medical case records. However, when we set out to study these records, we found that they were far from accessible.

An overview of the research in progress

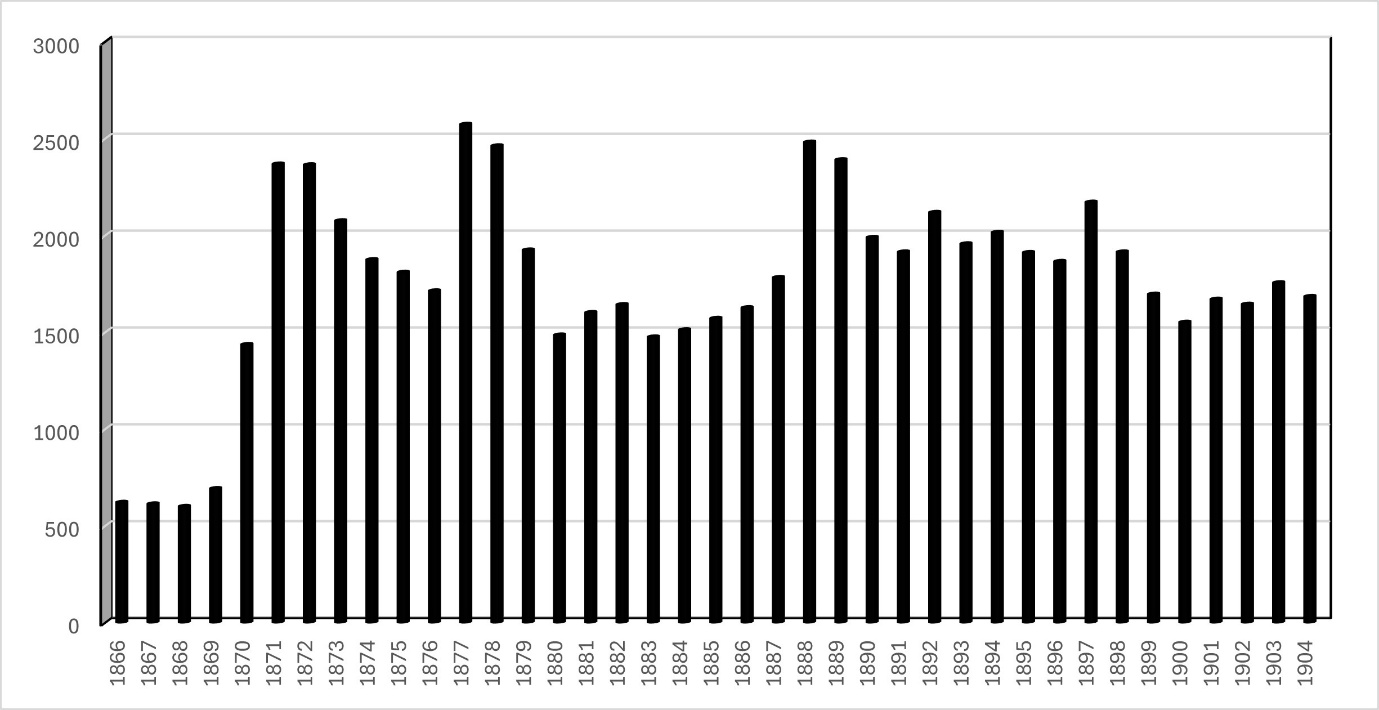

Authors SD and SRK have specialised in history and clinical psychology, respectively, and we employ archival methodology in our ongoing research. SD’s doctoral research, “Famines as Social Crises in Colonial South India from 1865 to 1901 CE” (with special reference to the great famine of 1876–78 or Tātu Varuṭap Pañcam in Tamil) offers pivotal insights on mental health issues in colonial South India. The incidence of suicides rose during the famine (Figure 2), with a higher prevalence among women than men. Additionally, admissions to lunatic asylums increased, with male admissions surpassing those of females. These preliminary findings led us to examine the annual reports of lunatic asylums in the Madras Presidency, which revealed that most of the admissions were of “coolies”c (landless people engaged in rural labour) [18]. This troubling phenomenon spurred our investigation of socio-political events, mental health vulnerabilities, and consequent (medical) discourses in colonial South India from 1858 to 1947.

Figure 2. Number of registered suicide cases in Madras Presidency from 1866 to 1901 (Source, available online only)

We use a critical postcolonial framework to investigate the role of archives in understanding the mental health system in colonial South India. Through this research, we not only undertake a historical examination of mental health but also acknowledge colonialism’s continued influence on modern mental health research and practice.

SD, who did the fieldwork, is an Indian female historian exploring critical mental health studies, who struggled to negotiate with archival systems during her research. She observed that some records from the second half of the nineteenth century are housed in a particular archive that is only accessible to those who are affluent enough to influence the system through power and cultural resources.

SRK is a queer clinical psychologist who, unsurprisingly, was not extended compassion and empathy by mainstream mental health professionals, who are apolitical, ahistorical, and acultural, and present a value-neutral, “vending machine” kind of mental healthcare, where profound emotional landscapes are trained into silence. His research and writings are guided by an “ethic of care” and “epistemic justice” perspective, centred on giving marginalised people the “permission to narrate” and calling attention to the need to nurture humane mental healthcare ecosystems that are responsive to alterity and regard care as a central value.

Nature of the data: Unavailability as evidenceAs part of our research, SD visited two state government-run archives, four libraries, two mental health institutions, and three administrative departments (the Directorate of Medical and Rural Health Service, the Health and Family Welfare Department, and the City Corporation Office) in two states of South India to collect archival sources and the medical case records of patientsd admitted to former lunatic asylums. One of the state archives informed SD that they did not possess such records. Then, SD visited state-run mental health institutions and found that they had not made any efforts to preserve colonial case records. In the health and family welfare department, although SD was permitted “official” access to an old record room situated on their premises, subordinate staff denied her entry. In-person visits to two mental health institutions and email communications with bureaucrats and three asylum-turned-mental-health-institutions proved similarly futile. When she requested access to other documents from the late nineteenth century in the archives, staff said that it was “very difficult to access them” due to their brittle condition. We spent 33 days running in vain from pillar to post. Though we could access twentieth-century government proceedings from different departments — public, revenue, health, and judicial — and the public department fortnightly letters in the archives, crucial sources, such as medical case records and the government proceedings of various departments from the late nineteenth century, remain inaccessible. Accessing records from the “Great Famine” period remains especially challenging.

We posit that the unavailability of medical case records in mental health institutions, and the lack of intersectoral coordination and interest in preserving them, points towards historical insensitivity and a lack of attention to the socio-structural factors shaping mental health historically and intergenerationally, at least with respect to institutional attitudes towards archives. This journey compelled us to critically introspect on our research trajectory, hindered by inaccessibility and consequent hurdles, which we analyse and discuss further.

Discussion

As history plays a pivotal role in determining the current status of mental health (care), it is crucial to examine the colonial period to grasp systemic challenges, the lived experiences of Indigenous communities, and the resultant ethical questions. Archival sources and medical case records are essential for reconstructing the mental health history of colonial South India. However, the non-accessibility of archival sources, the slow processing of requests, and the absence of a cooperative research environment are long-standing issues that hinder research in India. We did not find evidence to show that any of the colonial asylum-turned-mental health institutions in south India made effort to preserve colonial medical case records and make them accessible to researchers. The lack of social sensitivity among mental health professionals invalidates the influence of historical factors underpinning mental health issues. We discuss these issues in detail in the upcoming section.

“It’s very difficult to access sources on the second half of the nineteenth century”: Apathy and denial“Why is it easier to access India’s history through archival collections in the United States, United Kingdom and Europe than within India itself?” was an important question raised in the Tiffen Talk lecture series held at the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, New Delhi [19]. In the era of digital archives, there is a need to examine their accessibility. The non-accessibility of documents from certain periods (like the second half of the nineteenth century), the slow processing of requests, and the absence of a cooperative research environment to access necessary archival sources in a few Indian archives continue to pose barriers for researchers. “It is very difficult to access documents from the second half of the nineteenth century” is an oft-quoted statement author SD has heard from a state archive for more than a decade. — SD was asked by a staff member at an archive to study the twentieth century instead of the nineteenth century. This was in 2014, while struggling to collect sources for her PhD — done in the UK under the Charles Wallace India Trust grant. Yet, even in 2024, records of this period were inaccessible, underscoring the negligence in preservation management. Our request for data was not processed for a few days when we questioned the prolonged inaccessibility. Another mental health historian reported a similar experience: she was denied access to the archives when she pointed out that scholars are allowed access to up to 30 files daily from the National Archives of India [20]. Patel, a historian, reminds us that scholars are forced to look abroad, as Indian archives remain inefficient and discouraging for researchers [21].

Archivists and historical research“No research scholar shall call for or consult records which are not relevant to the subject of his research.” This is one of the rules in a state archive. Who decides which document is relevant (or not) to the researcher? How should this be decided? Do all the archives in the country have qualified historians who can vet requests in the research hall?

Since archives play a dual role as preservers and providers of historical documents, we expect historians to be at the helm of their administration. Unfortunately, this is a rare phenomenon. When we requested Fortnightly Letters/Reports (confidential, timely updates sent by the Government of Madras to the Government of India during 1914–1957 on a range of matters, including administration, political and judicial issues, economics, the press, finance, and climate) we were asked to request for records exclusively related to lunatic asylums. Trying to fit sources within a particular box can hinder the free thinking of researchers, particularly in mental health research, which may require an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary approach. The slow processing of requests is another problem stemming from staff shortages. Patel opines that it is “hardly an understatement to say that, unless the Indian government gets serious about adequate funding and staffing of public archives and libraries, vast records of Indian history will turn literally to dust in the next few decades” 21]. Pillai adds to this contention: “To be able to preserve the history of the present we need to have historically and culturally informed and technologically capable archivists” [22: p 22].

Historical apathy of state-run mental health systemsIn South India, we found that three former colonial asylum-turned-mental-health-institutions, located in Chennai, Kozhikode, and Visakhapatnam, do not preserve their colonial-era mental health records. Similarly, three colonial asylum-turned-academic-mental-health-institutions under the Government of India, viz, the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru, the Lokopriya Gopinath Bordoloi Regional Institute of Mental Health, Tezpur, and the Central Institute of Psychiatry, Ranchi, have not taken steps to preserve these records and ensure their availability for research. We could not find any information about archival documents on their websites.

Rajpal expresses strong dissatisfaction with the loss of medical case records: “In the medical profession, where case histories play an imperative role in understanding and conceptualising diseases, this widespread ignorance cannot be forgiven. This unawareness reflects the ever-widening gap between the sciences and the social sciences” [20: p 20].

Archives, stories of suffering, and mental health ethicsArchives that centre lived experiences of the past through well-preserved records help re-construct the mental health history of a society. Constructing colonial history is crucial for understanding lived experiences of marginalised groups of oppression, prejudices, racism, and socio-economic, political, and structural violence. For instance, Indian prince Dyce Sombre (1808–1851) was the first Eurasian Member of the British Parliament (1841) to inherit a vast property, but colonial archives describe him as “insane”; his struggle to prove himself “normal” and legally claim his foster mother’s property went in vain. Several archival documents speak about his legal struggles, but they make no mention of his contributions as a parliamentarian and his struggle to claim his legitimate inheritance, which continued till his death. Archival research on Sombre’s life throws light on the biased observations, anti-Asian prejudice, and colonial discrimination seen in these documents [23, 24].

The book Prozak Diaries: Psychiatry and Generational Memory in Iran demonstrates that uncovering past experiences helps people re-imagine and re-negotiate what they felt, feared, desired, denied, repressed, remembered, or forgot [25]. Similarly, the absence of patients’ case records in mental health institutions sidelines the troubled relationship between mental health systems and socio-cultural, economic, and historical realities. Available and accessible archival sources are a crucial prerequisite for historical research. Muthukrishna et al opine that “(H)istorical data provide an excellent and underutilized source of information about the structure and function of a much broader range of human minds than psychologists typically study” [26]. Archives open a whole new world of lived experiences and stories of suffering that otherwise remain eclipsed in mainstream mental health training and research.

Social sensitivity of mental health professionalsWriting on the critical psychological history of India, Mishra and Padalia state that psychologists require a strong foundation in philosophy, the history of science, and politics to cultivate the critical consciousness required to meet the needs of marginalised groups [27]. However, the profession of psychiatry, which originated during colonial times, developed based on the Euro-American biomedical model, fails to address local problems due to the absence of interpretative social science training [27]. In addition, dominant Western epistemologies in mental health academia dismiss traditional Indian practices as “unscientific”; educational institutions and hospitals thus end up reproducing colonial attitudes. Bayetti et al argue that inter-disciplinary enquiries can help initiate the crucial dialogue between social science and mental health care, enhancing locally responsive clinical training and practice [28].

The way forward

History plays a pivotal role in mapping the mental health struggles of a society. Our attempts to understand the history of mental health in colonial South India remain largely unsuccessful due to the inaccessibility of medical case records and related archival sources. Poor preservation of documents, slow processing of requests, the absence of a cooperative research environment in the archives, and a lack of historical sensitivity in mental health institutions are major barriers. The following suggestions can help create an efficient ecosystem for historical research on mental health.

● Effective collaboration among archives, mental health institutions, and policymakers could facilitate intersectoral coordination.

● Accelerating the digitalisation process is crucial for historical research, particularly to shed light on mental health history.

● Recruitment of adequate staff in archives, a longstanding request of the academic community, must be addressed to resolve issues related to slow processing.

● The historical context of suffering needs to be emphasised in mental health training and practice to foster historically informed mental health research and practice in contemporary times.

● Preserving archives and making them accessible to researchers should be considered an ethical duty of mental health institutions, as they help us reimagine and question unjust mental health practices.

● Where are asylum case records to be found? Mental health professionals and the government must collaborate to solve this important puzzle and relocate them.

Conclusion

Studying the historical context of mental health helps clinicians grapple with the nuances and complexities of the interrelationships between history, culture, and mental health. Historical consciousness helps cultivate cultural sensitivity among mental health professionals, which is essential for providing ethical mental health services. It is important to incorporate stories of historical wrongs and associated sufferings into professional mental health training, eg, the complicity of mental health systems in India in aggravating the suffering of LGBTQIA+ people by labelling them as pathological [29]. Despite progress in psychiatry, the medicalisation of socio-political issues as individual mental health problems is widespread. Critical studies in mental health that incorporate qualitative methodologies are imperative to building sensitivity concerning historical issues that still plague the mental health system in unforeseen ways. Hence, an understanding of the intersectoral linkages among mental health institutions, archival systems, and policymaking bodies is vital for realising an ethical and people-centred mental healthcare ecosystem.

Notes:

a Under the “indentured labour system”, the labourer and employer sign a contract for a specific period, and the labourers who sign it are referred to as “indentured labourers” [30].

b After 1920, these institutions were called “mental hospitals.” [31]

c The term “coolie” comes from the Tamil word kuli, meaning “wages” or “hire”. Portuguese merchants on the Coromandel Coast in India first used it in the late sixteenth century to describe men carrying loads at the docks. Over time, it evolved to refer to anyone hired for menial labour [32].

d The term “patient” is mentioned in official colonial reports. [18

Authors: Sathya D (corresponding author — sathyahistory14@iitpkd.ac.in, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1252-8481), Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Palakkad, Kanjikode, Kerala 678623, INDIA; Sudarshan R Kottai (sudarshan@iitpkd.ac.in, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2564-4879), Assistant Professor, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Palakkad, Kanjikode, Kerala 678623, INDIA.

Conflict of Interest: None Funding: None

To cite: Sathya D, Kottai SR. Archives, mental health systems, and the history of mental health in colonial South India: Critical questions. Indian J Med Ethics. 2026 Jan-Mar; 11(1) NS: 49-54. DOI: 10.20529/IJME.2025.092

Submission received: August 1, 2024

Submission accepted: April 3, 2025

Published online first: December 6, 2025

Manuscript Editor: Sayantan Datta

Peer Reviewer: Aritra Chatterjee

Copyediting: This manuscript was copyedited by The Clean Copy.

Copyright and license

©Indian Journal of Medical Ethics 2025: Open Access and Distributed under the Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits only noncommercial and non-modified sharing in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Salovey P, Bekenstein J. University statement. New Haven: The Yale & Slavery Research Project; 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 28]. Available from: https://yaleandslavery.yale.edu/university-statement

- Chidanand R. Yale fellow: well said: Ivy League icon named after India exploiters apologise for ties to slavery. The Times of India; 2024 Feb 18[cited 2024 Dec 28]. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/us/yale-university-apologizes-for-ties-to-slavery-in-india/articleshow/107799138.cms

- Maharaj-Ramdial S. The psychological impacts of indentureship: Then and now. London: Routledge; 2016[cited 2024 Dec 28]: 249 p. In: Hassankhan MS, Roopnarine L, Ramsoedh H, editors. The legacy of Indian indenture. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315272023-19/sandili-maharaj-ramdial

- Arora PG, Persaud S, Parr K. Risk and protective factors for suicide among Guyanese youth: Youth and stakeholder perspectives. Int J Psychol. 2020 [cited 2024 Aug 21] Aug;55(4):618-28. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12625

- Carrasco H, Messac L, Holmes SM. Misrecognition and critical consciousness – An 18-month-old boy with pneumonia and chronic malnutrition. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(25):2385–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1902028

- Kleinman A, Das V. Lock M. Social suffering. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1997.

- Barnett JE, Bivings ND. Culturally sensitive treatment and ethical practice. The Maryland Psychologist. 2002[cited 2024 Dec 28];48(2). https://www.apadivisions.org/division-31/publications/articles/maryland/barnett-ethical.pdf

- Kirmayer LJ. Rethinking cultural competence. Transcult Psychiatry. 2012;49(2):149–64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1363461512444673

- Metzl JM. The protest psychosis: How schizophrenia became a black disease. Massachusetts: Beacon Press; 2010. X p.

- Report of the Health Survey and Development Committee. Vol III. Appendices. Simla: Govt Press; 1946. 64 p. https://www.rfhha.org/images/public_health/health_committee%20/1.3%20Bhore_Committee_Report_VOLIII.pdf

- Qureshi F, Misra S, Poshni A. The partition of India through the lens of historical trauma: Intergenerational effects on immigrant health in the South Asian diaspora. SSM-Mental Health. 2023[cited 2024 Dec 28];100246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2023.100246

- Kanagaratnam P, Rummens JA, Toner VAB. “We are all alive… but dead”: Cultural meanings of war trauma in the Tamil diaspora and implications for service delivery. Sage Open. 2020 Oct[cited 2024 Dec 28]. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020963563 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2158244020963563

- Basu AR, Murthy RS. Disaster and mental health: Revisiting Bhopal. Econ Political Wkly. 2003 Mar 15-21[cited 2024 Dec 28]:38(11):1074–82. Available from: https://www.epw.in/journal/2003/11/special-articles/disaster-and-mental-health.html

- Sharma R. Gujarat earthquake causes major mental health problems. BMJ. 2002[cited 2024 Dec 28];324(7332):259. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7332.259c

- Arawi T. War on healthcare services in Gaza. Indian J Med Ethics. 2024[cited 2024 Dec 28];9(2):130. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2024.004

- World Health Organization. Reaching patients with severe mental health disorders: WHO hands over 12 vehicles for community health providers in Ukraine. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2024 Mar 12[cited 2025 Jan 12]. https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/12-03-2024-reaching-patients-with-severe-mental-health-disorders–who-hands-over-12-vehicles-for-community-health-providers-in-ukraine

- Antic A, Abarca-Brown G, Moghnieh L, Rajpal S. Toward a new relationship between history and global mental health. SSM-Mental Health. 2023[cited 2024 Dec 28]; 4:100265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2023.100265

- Annual report of the lunatic asylum in the Madras Presidency during the year 1877–78. Madras: Government Press; 1878. 36 p. Available from: https://digital.nls.uk/indiapapers/browse/archive/82807913

- The Centre for Social and Economic Progress. The future of India’s strategic history: Archival research and policy impact. Event summary. 2022 Nov 30[cited 2024 July 19]. Available from: https://csep.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/The-Future-of-India-Strategic-History.pdf

- Rajpal S. Experiencing the Indian archives. Econ Political Wkly. 2012 Apr 21 [Cited 2024 Jul 5];47(16):19–21. Available from: https://www.epw.in/journal/2012/16/commentary/experiencing-indian-archives.html

- Patel D. India’s troubled archives and libraries. Dinyar Patel website. 2012 Mar 27[cited 2024 Jul 15]. Available from: https://dinyarpatel.com/2012/03/27/indias-troubled-archives-and-libraries/

- Pillai S. Old archival laws, new archives. Econ Political Wkly. 2013[Cited 2025 Nov 26];48(3):20–2. Available from: https://www.epw.in/journal/2013/03/commentary/old-archival-laws-new-archives.html

- Aziz S. National archives of India: The colonisation of knowledge and politics of preservation. Econ Political Wkly. 2017[Cited 2025 Nov 26];52 (50):33–9. Available from: https://www.epw.in/journal/2017/50/perspectives/national-archives-india.html

- Pies R, Fisher MH, Haldipur CV. The mysterious illness of Dyce Sombre. Innov Clin Neuro Sci. 2012;9(3):10. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3342989/

- Behrouzan O. Prozak Diaries: Psychiatry and generational memory in Iran. California: Stanford University Press; 2020.

- Muthukrishna M, Henrich J, Slingerland E. Psychology as a historical science. Annu Rev Psychol. 2021;72(1):717–49. Available from: https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-psych-082820-111436

- Mishra AK, Padalia D. Re-envisioning psychology: A critical history of psychology in India [Internet]. In: Misra G, Sanyal N, De S, editors. Psychology in Modern India: Historical, methodological, and future perspectives. Singapore: Springer; 2021 [cited 2024 Dec 29].: p.163–201 pp. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-4705-5_10

- Bayetti C, Jadhav S. Deshpande SN. How do psychiatrists in India construct their professional identity? A critical literature review. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59(1):27–38. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/indianjpsychiatry/fulltext/2017/59010/how_do_psychiatrists_in_india_construct_their.8.aspx

- Kottai SR, Ranganathan S. Fractured narratives of psy disciplines and the LGBTQIA+ rights movement in India: A critical examination. Indian J Med Ethics. 2019;4(2):100–110. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2019.009

- Lal BV. Indian indenture: History and historiography in a nutshell. J Indenturesh Legacies. 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 24] Sep 1;1(1):1-5. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.13169/jofstudindentleg.1.1.0001

- Daund M, Sonavane S, Shrivastava A, Desousa A, Kumawat S. Mental Hospitals in India: Reforms for the future. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018 [cited 2025 Sep 24] Feb 1;60(Suppl 2):S239-47. DOI: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_434_17

- Damir-Geilsdorf S, Lindner U, Müller G, Tappe O, Zeuske M. Bonded Labour: Global and Comparative Perspectives (18th–21st Century). Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag; 2016.