COMMENT

Capacity building of community health workers: One size does not fit both rural and urban settings

Anuj Prakash Ghanekar

DOI:10.20529/IJME.2022.078Abstract

The Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) programme in India is the world’s largest all-female Community Health Workers (CHWs) programme. ASHAs are supposed to bridge the gap between community and health services by functioning as healthcare catalysts, service providers, and community-level health activists. This paper discusses the ethical challenges posed by using the same template for capacity building of ASHAs in rural and urban contexts, without accounting for the differences. Urban heterogeneity and rapidly growing urbanisation demand special attention for crucial programme activities like the capacity-building of ASHAs. When the relevant literature like policy and programme documents, training modules, and implementation guidelines were analysed, it was evident that the simple transplantation of rural models to urban contexts would not be a useful strategy. The recommended areas for improvement are the urban-specific customisation of the roles of ASHAs, the consideration of urban heterogeneity in the training content and pedagogy, utilising the advantages of the urban set-up, ensuring supportive supervision mechanisms for ASHAs, strengthening overall inter-sectoral convergence and community processes in urban areas.

Tailoring programmes to address the urban-rural dichotomy can be a positive step towards preserving the core values expected to be the basis of public health, like human rights, liberty, equality, and social and environmental justice. In a broader sense, the recommended evidence-informed practice would encourage integration of the ideals and standards of ethics within the structure of professional activity in public health.

Keywords: ASHA, Community Health Workers, Gujarat, public health ethics, urban, rural

ASHA (which means hope in Hindi) are more than 1 million female volunteers in India honoured for the crucial role in linking the community with the health system, to ensure those living in rural poverty can access primary healthcare services, as shown throughout the Covid-19 pandemic — a release from the World Health Organization (WHO) while honouring the Global Health Leaders Award-2022 to the ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) workers from India [1].

Introduction

India is rapidly urbanising following a worldwide trend, with 31.1% of the population found living in cities [2]. A United Nations survey indicates that 40.9% of the country’s population will reside in urban areas by 2030 [3]. The drivers of urbanisation are rural to urban migration, reclassification of towns, and expansion of existing urban boundaries and natural growth of the urban population. Urban settings have their advantages as well as drawbacks.

In urban India, community health work is carried out by the ASHA workers — the largest all-female Community Health Workers (CHWs) programme in the world [4]. As per current estimates, approximately 9,00,000 ASHAs in rural, and over 64,000 ASHAs in urban areas work under the National Health Mission (NHM) of India [5]. ASHAs within the health system of India are viewed as key to fast-tracking universal health coverage, achieving an adequate quality of service during delivery, and ensuring comprehensive and accessible primary healthcare. The ASHA cadre includes females with variable levels of formal training. They often belong to local communities and are expected to work within their own communities.

An ASHA, as a community health functionary, is expected to take the responsibility of a change agent in health. Villages, being a more homogeneous community compared to urban locals, provide scope for the rural ASHA, enabling her in carrying out the expected functions like creating awareness of health and its social determinants, mobilising the community towards local health planning and increased utilisation and accountability in the existing health services. The programme has been used for nearly two decades, to boost access to health services in rural settings. It is comparatively recent in urban settings where the National Urban Health Mission (NUHM) was launched in 2013-14. There are similarities and distinctions in the design, scope, and implementation of the ASHA programme in rural and urban contexts.

The present paper studies the adaptability of the ASHA cadre-based health services by focusing attention on the different realities of urban and rural settings. This argument is in alignment with the recent call by the WHO and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) for access to primary and secondary health services in urban settings to achieve universal health coverage and health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) [6].

There is a need for ethical analysis of the public health practice of using similar training processes for rural and urban ASHAs. In India, urban areas are rapidly changing, and obtaining information about these changes is not easy. The Public Health Code of Ethics requires that personnel have the skills to evaluate possible solutions, keeping the process open to revision. Therefore, in this context, public health ethics calls for careful reflection on the changing ground realities and adapting decisions to suit them [7].

The field of public health must address communal and systemic factors, to realise values like human rights, liberty, equality, and social and environmental justice [7, 8]. Customising programmes addressing the urban-rural dichotomy can be a step towards that. For instance, professionalism and trust in public health would necessarily include evidence-informed practice based on urban-rural differentiation. The customised approach would prevent, minimise, and mitigate the health harms experienced by excluded urban communities. This approach would help to achieve justice and equity in health for marginalised sections and strengthen the core value of engaging with diverse communities.

There has been a demand for more empirical research in public health ethics to examine specific areas of public health policy and practice, and to bring the findings of such research to the attention of public health practitioners [7]. The argument presented in this paper could be useful to address the fundamental question of how ethical norms can be integrated into the structures of professional activity in public health.

Methods

Under the Indian Constitution, health is a state subject and in terms of implementation of programmes, contexts matter to a large extent. To illustrate this, this paper demonstrates an analysis of urban Gujarat — the state being one of the most rapidly urbanising in India [9]. The objective was to examine the rural and urban contexts and healthcare needs, to match them with capacity-building measures involved in the programme provisioning by ASHA workers across these two contexts. The identified policy and programmatic documents including training modules and programme implementation guidelines were analysed thematically to identify the requirements and gaps in the training of ASHAs across rural and urban areas.

Discussion

Urban not equal to ruralAn analysis of urban Gujarat from secondary data revealed that in-migration and high population density [10], coupled with poor environmental conditions like lack of access to safe drinking water, waste-water management and toilets [11] make urban areas potential hotspots for the rapid spread of emerging infectious diseases. A negatively skewed sex ratio [12], lower labour force participation of women, and rare female ownership of houses [10] in urban areas further indicated a gendered impact on health. In the period from 2015-16 to 2020-21, urban indicators like antenatal care visits, consumption of iron and folic acid, institutional deliveries, the infant mortality rate, under-5 mortality rate and malnutrition among children did not show progress in urban Gujarat, even though its urban performance is relatively better than the rural [12, 13]. Indicators like preference for private facilities for vaccination, the rising trend of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), ever-married women aged 18-49 years who have experienced physical violence during any pregnancy, are also noteworthy in urban contexts [12]. The popular perception that “cities are better than villages” is true to some extent. But inequality and exclusion are also prominent characteristics of urban areas and are termed “urban penalty” [14]. The role of CHWs is crucial in addressing urban/rural differences in community health work. A CHW is supposed to bridge the gap between community and health services by functioning as a healthcare catalyst, a service provider, and a health activist at the community level [15].

Critical need for urban adaptation of capacity building models for ASHAsWithin the health systems framework, ASHAs constitute the “human resource” block. Capacity building of this group of CHWs will have an impact on the performance of the health system as a whole. This ethics-based analysis proposes to examine the approaches to capacity building for urban ASHAs. The need for examining such approaches falls within the ambit of “permissibility” in the eight-point framework of ethical analysis of public health interventions as provided by the American Public Health Association’s Public Health Code of Ethics [7]. The other seven considerations of this framework are: respect, reciprocity, effectiveness, responsible use of scarce resources, proportionality, accountability, and public participation.

The ASHAs’ demands for fixed salaries, being brought within the purview of existing labour laws, their struggles with their allotted Covid duties have already been documented [16, 17, 18]. However, their specific needs when working in urban areas have yet to be identified [19].

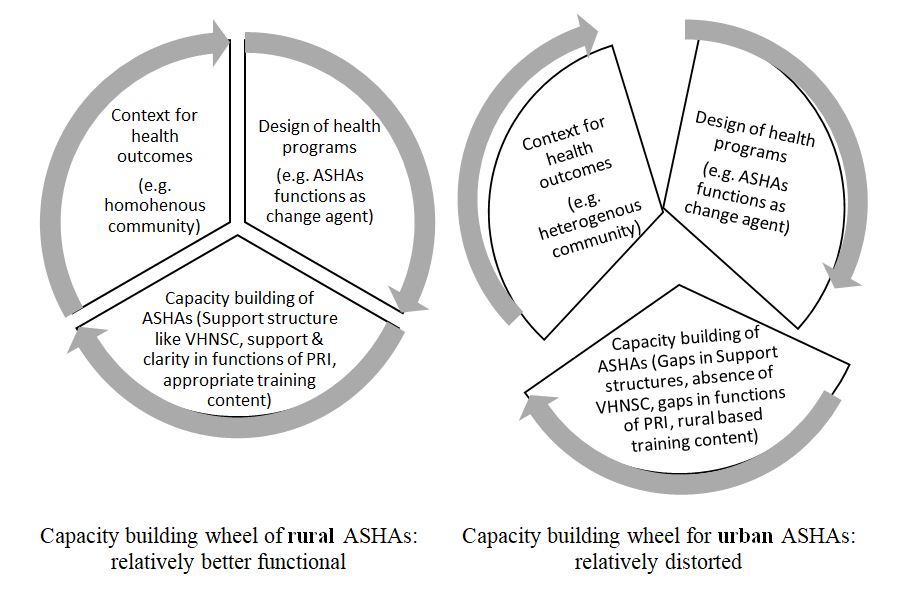

Figure 1 depicts the divergence in urban and rural contexts, the demand for a more flexible design of ASHA programme model and community health service delivery in general, and subsequently the capacity building efforts of ASHAs that must differ with differing urban-rural contexts. The existing models for capacity building for rural and urban ASHA workers were analysed — using the national level and Gujarat state specific protocols [20, 21, 22, 23] — to explain the ethical imperative for variation in training.

The following themes were identified to posit the argument. Figure 1. Urban rural differentials and the role of ASHA workers

According to the official norms for ASHA selection [15], one ASHA per 1000 population is appointed in a village. In cities where the population is 50,000 or more, one ASHA is selected for every 2000-2500 population. National Health Mission (Gujarat) data (August 2021) indicated that there were 43,314 ASHAs working in the state, in both rural and urban areas, against the sanctioned 45,345 [15].

The substantial shortage of health workers can be observed as a challenge to the public health system, whether it is urban or rural Gujarat. However, the gap in provisioning can more clearly be observed only in urban areas, where 4,549 ASHAs are available, against the desired number of 10,298 as per the norm of one ASHA for 2500 urban population [15].

Activities of urban or rural ASHAs are home visits, maintaining records, attending Village and Urban Health and Nutrition Days (VHND or UHND), holding Village Health Sanitation Nutrition Committee (VHSNC) or Mahila Arogya Samiti (Women’s Health Committees —MAS) meetings, and visits to the health facility. These are elaborated in a customised manner for urban and rural areas in the induction training module for ASHAs [20, 21]. However, there is further scope for urban-specific modifications in the role of ASHAs. Even in a state like Chhattisgarh, known for the key role played by Mitanins (CHWs) in community-level care, the urban Mitanins did not demonstrate the same degree of social access to the marginalised as compared to rural CHWs [24]. Some areas for strengthening the role of urban ASHAs are listed below.

Population density an advantage in accessing clientsPhysical access to clients, say, the household distance from health centres is not a barrier for urban areas, unlike the rural scenario. Hence, ASHAs in urban areas have the additional benefit of being able to visit more clients. Keeping this in mind, urban ASHAs can be oriented towards leveraging these “urban” advantages. Equipping urban ASHAs with training to focus on the health needs of marginalised groups has already been advised by the Technical Resource Group for NUHM to increase population coverage [24].

Potential to use media resources for health educationIn the urban context, it is possible to explore varied media to supplement health education along with the direct contact. For example, ASHA help desks at the primary health centre have been suggested to educate people on beneficial actions like the use of publicly financed insurance for the poor [24]. ASHAs in many cities have demonstrated the effective use of social media-based communication during the pandemic and related lockdowns. These skills can be extended to form social media support groups and utilise the accessible urban mobile networks.

Redundancy of specific roles of ASHAsDue to greater diversity and availability of healthcare providers in urban settings, some of the roles played by ASHAs may be redundant or irrelevant there, eg commodity distribution or service provision. For instance, a study with urban health workers in Burkina Faso revealed low uptake of community-based treatment of malaria due to the presence of other healthcare providers [25]. ASHAs often perform different roles under various programmes. These include providing care, mobilising the community and facilitating the scheduled campaigns. In the urban scenario, considering the high population density, these roles of ASHAs can be merged wherever appropriate to save time. Urban ASHAs can be assigned a greater role in the control of non-communicable diseases, a major emerging urban health challenge [24]. The prevalence of local healers and unregistered healthcare providers in urban areas can be acknowledged, and the verified resources can be integrated into the health system in meaningful ways, with ASHAs serving as a connecting link.

Consideration of urban heterogeneityA rural ASHA is expected to cater to the entire village and to focus specifically on marginalised and vulnerable sections. The geographical scope is often uniform. However, for an urban ASHA, the geography can vary in slum, slum-like, and non-slum areas. In settlements of the urban poor, there are fewer organic communities — ie communities bound by a common culture — than one finds in villages [24]. Urban heterogeneity is multi-dimensional and includes migrant community pockets. Such migrant sub-groups can have additional needs for cultural competence like language compatibility, in addition to physical access. For instance, the local language (Gujarati) version of this induction training module is available [15]. Training modules for ASHAs, however need to be available in multiple languages relevant for the respective urban setting. Additionally, there can be construction sites, homeless populations, colonies of commercial sex workers, resettled colonies for economically weaker sections, all rendering the geographical scope heterogeneous. There can be greater clarity regarding geographical scope for an urban ASHA, so that she can target her services in a focused manner. Assessment of training modules also revealed the ambiguity of whether an urban ASHA is supposed to act at the slum or ward levels. Further, many urban communities are dynamic in nature. There is a continuous inflow and outflow of people. This might interrupt and prevent efficient delivery of community health work. This should also be addressed through appropriate training.

Urban specific training and supportive supervisionCapacity building of ASHAs is considered a continuous process. According to the norms, each ASHA, whether rural or urban, receives induction training for eight days within three months of joining. Then, she is trained in modules 6 and 7 for twenty days in four rounds, and every year she receives a refresher training of five days [15].

While the induction training module has been designed for urban ASHAs by NHM, it is derived from the module for rural ASHAs. However, the lack of other specifically urban modules, both in the modular training series and in the refresher training modules persists. The literature has also endorsed such a need; for instance, a study conducted in Dhaka, Bangladesh, comments on the importance of the role of refresher training associated with longer retention of community health volunteers in urban settings [26].

The modules introduce vulnerable groups among the urban poor like beggars, street children, construction workers, porters, rickshaw pullers, sex workers, street vendors, and migrant workers. However, training for urban ASHA workers in the skills required to enable participation from such a heterogeneous group was found missing. Living and working conditions of urban population groups need to be considered in-depth while chalking out the urban ASHA’s role; for example, the daily routine of urban and rural populations is varied and will probably affect the work schedule of ASHAs. These factors could ultimately affect health service utilisation and outcome indicators. This also resonates with the values set out in the Alma-Ata Declaration, which reinforces effective primary healthcare as reliant “at local and referral levels, on health workers, including … community workers … suitably trained socially and technically to work as a health team and to respond to the expressed health needs of the community.” [27]

Urban areas have the pivotal presence of private actors like medical practitioners, schools, NGOs, etc; however, urban ASHAs are not oriented to considering the role of private actors in the health management of community members. The current modules do mention collaboration with different sectors like the Health Department, Education Department, Urban Local Bodies, Women and Child Development, and Local NGOs. However, it is beyond the capacity of ASHAs or MAS alone to initiate these collaborations. There may be already existing formal collaborations at practice level between the health sector and other sectors of urban local bodies (ULB), the health administration and elected representatives, as well as the health sector and private actors including NGOs. This existing convergence would create a conducive environment for ASHAs to function. Technical Resource Group recommendations on NUHM have endorsed the role of such collaborations [24].

In capacity building, skills play an important role apart from knowledge. The ethical dialogue on the standard of care in the training of health workers considers the lack of skill-building of health workers as a waste of resources and an unethical policy [28]. Skill-building must be done in the context of urban-specific scenarios; however, the skill-building section of induction modules includes the same examples, whether it is rural or urban. For instance, counselling skills on malnutrition give the very same example in a rural module [20: pg 84] and in an urban module [21: pg 96]. Scholars have argued for innovative approaches to support the evolution of urban CHW roles that are oriented towards the kinds of urban challenges and opportunities [29]. The role of context-specific skill building and preparation of health workers has been highlighted previously. For example, a review study on Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs) revealed the absence of the training and skills to provide delivery care results in ANMs underprepared for work in rural areas. This gap can be overcome by measures like good pre-service training, supportive supervision, recognition and rewards, and a functioning health system for backup support [30].

The urban module for ASHAs covers an account of additional urban-specific conditions like dengue, chikungunya, and non-communicable diseases. This focus is important, however, there is a need to further expand the spectrum, covering issues of road traffic accidents, injuries, violence, overnutrition, urban specific climate change disasters and associated health problems, mental health, etc, which are typically urban health challenges. Further, the conditions included in both urban and rural induction modules, like HIV, malaria, diarrhoea, etc, have different underlying socio-cultural causes in urban and rural settings.

Different formats and case studies included in the module must cover urban ground realities in pedagogy. There is a differential vulnerability assessment tool for the urban setting. It is a welcome step but needs to be updated and revised from city to city.

ASHA facilitators have been selected to support and guide ASHAs in the implementation of various health programmes and health-related schemes in the community. ASHA facilitators are present in both rural and urban areas and that is a beneficial aspect of the model.

Urban support structures and community processes for ASHAsFor rural ASHAs, the specific role of Village Health, Sanitation, and Nutrition Committees (VHSNC) in field support and mentoring of ASHAs are defined. An ASHA works as a member or member secretary of the VHSNC. In fact, if an ASHA wants to resign from her duties, she is expected to submit her resignation to the VHSNC. The VHSNC is considered as the platform for taking “local level community action” for monitoring health status and undertaking local level health planning. The VHSNC includes the panchayat representatives, the anganwadi workers, the ANM, and other community members, particularly women, and the marginalised. The ASHA and VHSNC are expected to function in a coordinated manner to ensure the achievement of positive health outcomes at the community level, like developing a comprehensive village health plan [22].

Such a structure for supporting ASHAs in an urban setting is formed in terms of Mahila Arogya Samitis (MAS). However, the structure has the following limitations compared to its rural counterpart.

Limited representation of stakeholders within MASMAS, in its inherent structure, is women-specific and does not highlight the role of men in community health action. It also lacks the defined role and accountability of elected representatives, unlike the VHSNC. Without the involvement of elected representatives, there might be limited scope for leveraging any health action plans advocated by MAS. One of the mechanisms suggested in policy discourse to overcome this gap is of creating Jan Kalyan Samitis at the ward level [24], a step also advocated by the recent “Health and Wellness Centre” programme guidelines (2018) [31].

Challenges faced in galvanising community actionsIn urban areas, the absence of social cohesion weakens the bonds among residents of a community. This poses challenges in organising the community activities [24]. There are parallel structures to VHSNC like “ward committees” in the urban areas involving the role of elected representatives, but the role of such committees in health concerns or in support of ASHAs is not exclusively addressed in ASHA training material or MAS guidelines. Addressing the complex social determinants of health like mobilising the community for action against gender-based violence requires collective action and adequate support to ASHAs. This support can be availed of through organised VHSNCs by rural ASHAs and by encouraging the men’s participation, but this might not be possible for their urban counterparts unless MAS are empowered. Considering community empowerment to be a legitimate goal of health interventions, such structures are necessary. VHSNC can possibly have a better hold on improvement in sectors like drinking water or village cleanliness which impact health outcomes. This role is part of the VHSNC design; however, such a critical role is not outlined explicitly for MAS and urban ASHAs. Further, there are challenges in inter-sectoral coordination as mentioned in the earlier section. Lessons learned from NUHM from different states have endorsed the necessity of such structures in urban areas. [32]

Need for incorporating field lessonsGuidelines for community processes (VHSNC and ASHAs) were designed by the National Rural Health Mission in its first phase (2006) in consultation with the states and they were revised in the second phase (2013). Such guidelines for MAS are available (2015) but are relatively basic and require incorporation of grassroots lessons from the field. Some efforts are being made to execute this [23].

Further, the selection of rural ASHAs is done by a resolution of the gram panchayat (village council) in the gram sabha (local body of all registered voters in a village)a. A central principle undergirding the ASHA programme is community participation [22]. The ASHA policy is based on local residency and community-based selection. The women are selected from and are accountable to the village in which they reside. There are clearly defined roles and responsibilities of the panchayati raj institutions and gram sabha in the selection of rural ASHAs. In urban settings, structures like the village panchayat and gram sabha which facilitate the selection of ASHAs are replaced with ward committees and ward sabhas. NUHM has recommended ASHA selection committees at the city level and protocols have been set up for this. [33]. However, the tremendous fragmentation of urban communities might require substantial effort to strengthen this selection process.

Conclusion and the way forward

Growing urbanisation demands viable approaches for increasing access to health services in urban settings. This becomes even more crucial when the global and national policymakers deliberate on approaches to achieve health-related SDGs.

ASHAs are the critical connecting links between service providers and community members. Their importance is widely recognised. However, urban and rural contexts are distinct in terms of socio-demographic, economic, and environmental factors. This difference has been demonstrated in this paper with an analysis of the rapidly urbanising state of Gujarat.

The challenge of shortage of urban health workers must be addressed first. The role of urban ASHAs in programme design itself can be customised as per specifically urban conditions like high population density, greater heterogeneity and variation in community processes. Some existing training modules like the induction module cover urban-specific concerns; however, simple transplantation of rural models to urban contexts would not be a useful strategy. Skills like facilitating of community participation and collaboration between different stakeholders must be addressed differently using urban-specific training content and pedagogic tools like urban case studies. Urban support structures for ASHAs, like MAS, have inherent limitations when compared to rural counterparts like VHSNCs.

NUHM is in the process of developing separate guidelines for support structures. Examples of this include guidelines and tools for vulnerability mapping and assessment for urban health [34], a guidebook for enhancing the performance of ANMs in urban areas [35], etc. This is a welcome step and will eventually support urban ASHAs. There are some state-specific urban ASHA capacity-building efforts too, which have been piloted by different international and national funding agencies, for example, “The Challenge Initiative” in Uttar Pradesh, keeping family planning as a goal. This model supported urban ASHAs with job-aids, supervision by area ANMs, mapping and listing tools for the most vulnerable populations, follow-up strategies, convergence model with NGOs and health partners, a new payments system, monthly activity, etc [36]. There is scope to derive lessons from such state-specific efforts for further improvement in a general urban ASHA model.

Addressing the challenges faced by urban ASHAs would help to fulfil the general ethical considerations in public health like avoiding, preventing, and removing harms possibly experienced by the urban population, producing the maximal balance of benefits over harms, and distributing benefits and burdens fairly where urban and rural populations are concerned.

AcknowledgementsThe author acknowledges the contribution of the Rural Women’s Social Education Centre (RUWSEC) team, the Thakur Foundation, and all the expert faculty members and peers who contributed to the Public Health Ethics WriteShop. This WriteShop helped in the capacity building of the author. The author also acknowledges the specific and valuable contribution of mentor Prof Mala Ramanathan in the process of writing this research paper. The comments from anonymous reviewers and manuscript editor also helped to strengthen the article.

aNoteIn the villages of India, the gram panchayat (village council) constitutes the basic level of local government institutions. Gram panchayat has several administrative, judicial and social-economic functions. It is supposed to implement development programmes under the overarching mandate, supervision and monitoring of the gram sabha. The villagers are expected to use the forum of the gram sabha to discuss local governance and development and make need- based plans for the village.

References

- Express News Service, New Delhi. India’s ASHA workers among six recipients of Global Health Leaders Award at World Health Assembly. Indian Express. 2022 May 23 [Cited 2022 May 25]. Available from: https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/indias-asha-workers-six-recipients-global-health-leaders-award-world-health-assembly-7930873/

- Chandramouli, C. Census of India 2011: rural urban distribution of population. Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs: New Delhi; 2011. [Cited 2022 May 25]. Available from: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/1430/study-description

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). State of World Population 2007. Geneva: UNFPA; 2007 [Cited 2022 Sep 6]. p 6. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/695_filename_sowp2007_eng.pdf

- Ved R, Scott K, Gupta G, Ummer O, Singh S, Srivastava A, et al. How are gender inequalities facing India’s one million ASHAs being addressed? Policy origins and adaptations for the world’s largest all-female community health worker programme. Hum Resour Health. 2019[Cited 2022 May 25];17:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0338-0

- National Health Mission. Update on ASHA Programme. 2019 Jul [Cited 2022 May 25]. Available from: https://nhsrcindia.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/ASHA%20Update%20July%202019.pdf

- World Health Organization (WHO). A Vision for Primary Health Care in the 21st Century: Towards Universal Health Coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: WHO; 2018[Cited 2022 May 25]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/328065

- American Public Health Association. Public Health Code of Ethics: Issue Brief. 2019.[Cited 2022 May 25].Available from:https://www.apha.org/-/media/files/pdf/membergroups/ethics/code_of_ethics.ashx

- Childress JF, Faden RR, Gaare RD, Gostin LO, Kahn J, Bonnie RJ, et al. Public health ethics: mapping the terrain. J Law Med Ethics. 2002 Summer;30(2):170-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-720x.2002.tb00384.x

- Jariwala VS. Urbanisation and its Trends in India – A Case of Gujarat, Artha-Vikas Journal of Economic Development. 2015 Dec 1:51(2): 72-85. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3072887

- Census of India 2011. General Population Tables (India, States and Union Territories, Table A-4, Part II). New NCT of Delhi. Ministry of Home Affairs. In: Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Government of Gujarat. 2016. Statistical Outline Gujarat State. Gandhinagar: Govt of Gujarat; 2016 pp 7 [Cited 2022 May 25]. Available from:http://14.139.60.153/bitstream/123456789/13104/1/Statistical%20outline%20Gujarat%20state%202016.pdf

- Census of India 2011. Series-H: Tables on Houses, Household amenities and assets. New NCT of Delhi. Ministry of Home Affairs. In: State of Housing in India, A statistical compendium. New Delhi: Govt of India; 2013 pp 19, 20, 23, 24 [Cited 2022 May 25]. Available from: https://mohua.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/Housing_in_India_Compendium_English_Version2.pdf

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS). National Family Health Survey: Gujarat Report. Mumbai: IIPS. 2019-21[Cited 2022 May 25]. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-5_FCTS/Gujarat.pdf

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS). National Family Health Survey: Gujarat Report. Mumbai: IIPS. 2015-16[Cited 2022 May 25]. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/pdf/NFHS4/GJ_FactSheet.pdf

- Galea S, Vlahov D. Urban health: evidence, challenges, and directions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:341-65. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144708

- National Health Mission, Government of Gujarat. [Cited 2022 May 25] Available from: https://nhm.gujarat.gov.in/asha.htm

- Rao B, Tewari S. Distress among health workers in COVID-19 fight. Article14.com. 2020 Jun 9. [Cited 2022 May 25] Available from: https://www.article-14.com/post/anger-distress-among-india-s-frontline-workers-in-fight-against-covid-19

- Abdel-All M, Angell B, Jan S, Howell M, Howard K, Abimbola S, Joshi R. What do community health workers want? Findings of a discrete choice experiment among Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2019 May 1;4(3):e001509.

- Steege R, Hawkins K. Gender and community health workers: three focus areas for programme managers and policy makers. CHW Central [Cited 2022 May 25] Available from: https://chwcentral.org/twg_article/gender-and-community-health-workers-three-focus-areas-for-programme-managers-and-policy-makers

- Wahl B, Lehtimaki S, Germann S, Schwalbe N. Expanding the use of community health workers in urban settings: a potential strategy for progress towards universal health coverage. Health Policy Plann. 2020 Feb 1;35(1):91-101

- National Health Mission, Govt of India. Induction Training module for ASHAs [Cited 2022 May 25]. Available from http://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/communitisation/asha/ASHA_Induction_Module_English.pdf

- National Health Mission, Government of India. Induction Training module for ASHAs in urban areas [Cited 2022 May 25]. Available from https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/NUHM/Training-Module/Induction_Training_Module_for_ASHAs.pdf

- National Rural Health Mission, Government of India. Guidelines for Community processes. 2014 [Cited 2022 May 25] Available from https://nhsrcindia.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/Community%20Processes%20Guidelines%202014%20%28English%29.pdf

- National Urban Health Mission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Govt of India. Guidelines for ASHA and Mahila Arogya Samiti in urban context. 2016 [Cited 2022 May 25] Available from: http://cghealth.nic.in/ehealth/2016/NUHMDOC/guidelines-for-mas-and-uasha.pdf

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Reports and recommendations of technical resource group for national urban health mission. 2014 [Cited 2022 May 25]. Available from: https://nhsrcindia.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/Report%20Recommendations%20of%20TRG%20for%20NUHM.pdf

- Druetz T, Ridde V, Kouanda S, Ly A, Diabaté S, Haddad S. Utilization of community health workers for malaria treatment: results from a three-year panel study in the districts of Kaya and Zorgho, Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2015 Feb 13;14(71):1-2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-015-0591-9

- Alam K, Oliveras E. Retention of female volunteer community health workers in Dhaka urban slums: a prospective cohort study. Hum Resour Health. 2014 May 20;12(29). https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-12-29

- International Conference on Primary Health Care. Declaration of Alma-Ata. WHO Chron. 1978 Nov [Cited 2022 May 25];32(11):428-30. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/almaata-declaration-en.pdf?sfvrsn=7b3c2167_2

- Cash R. Ethical issues in health workforce development. Bull World Health Organ. 2005 Apr [Cited 2022 May 25]; 83(4):280-4. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2626207/pdf/15868019.pdf

- Elsey H, Agyepong I, Huque R, Quayyem Z, Baral S, Ebenso B, et al. Rethinking health systems in the context of urbanisation: challenges from four rapidly urbanising low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2019 Jun 1;4(3):e001501.

- Mavalankar D, Vora K, Sharma B. The Midwifery Role of the Auxiliary Nurse Midwife: The Effect of Policy and Programmatic Changes. In: Sheikh K, George A, editors. Health Providers in India: On the Frontlines of Change. London: Routledge India; 2011. Pp 38-56.

- Ayushman Bharat. Comprehensive primary health care through health and wellness centers. Operational guidelines. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2018 [Cited 2022 May 25] Available from: https://ab-hwc.nhp.gov.in/download/document/45a4ab64b74ab124cfd853ec9a0127e4.pdf

- National Health Mission and NHSRC. Thrust areas under NUHM for states: Focus on community processes. [Cited 2022 May 25] Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/NUHM/Brochure.pdf

- National Health Mission. Guidelines on Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA). [Cited 2022 May 25]. Available from: https://www.nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/communitisation/task-group-reports/guidelines-on-asha.pdf

- National Urban Health Mission, Govt of India. Guidelines and Tools for Vulnerability Mapping and Assessment for Urban Health. 2017 [Cited 2022 May 25] Available from: https://www.nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/NUHM/Guidelines_and_tools_for_vulnerability_mapping.pdf

- National Urban Health Mission, Govt of India. Guidebook for Enhancing Performance of ANMs in Urban Areas. 2017 [Cited 2022 May 25] Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/NUHM/ANM_Guidebook_under_NUHM.pdf

- The Challenge Initiative. Enabling Urban ASHAs to Effectively Facilitate Utilization of Family Planning Services. 2020[Cited 2022 May 25]. Available from: https://www.psi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/PSI-HIA-2-ASHAs.pdf